Stereotypes About China in Dutch Primary Schools: the Role of Textbooks and Teachers in Perpetuating a Prejudiced Discourse on China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Fall Pulama

FALL 2020 PULAMAThe newsletter for supporters of Hale Makua Health Services Virtual Fundraisers Kupuna Stories New Initiative to Help the Learn about some fun virtual Read a sweet story about the life of Community Needs fundraisers happening on our one of our residents, and how Hale Read how we are partnering up to social media and website. Makua helps bring her family peace help those affected by the impacts of mind. of COVID-19. page 2 pages 5 page 6 TOP STORIES You Helped A Hero’s Journey to Recovery feeling of openness, and enjoyed sitting out in the sun and admiring the birds and plants. “Now, I can practically walk without a cane. Therapy has been wonderful. That’s probably the most positive thing you have going on here.” At her first physical therapy session, therapists started Margaret off slowly, having her stand up by the rails. Even this seemingly simple task was a difficult adjustment for Margaret physically. However, as the week progressed she was gradually able to stand and walk with a Margaret Cabbab is a Registered experience. “I really love it. It’s been very front wheel walker, and by the third week Nurse and one of the heroes working at restful,” Margaret said about her stay. “I she was going up the stairs on her own. Maui Memorial Medical Center who didn’t know how stressed I was, but with “When I came in, there was no way I made sacrifices to care for the community’s the same medication, my blood pressure could walk, stand, rollover in bed, or get up COVID-19 patients. -

The Dream of Ramón Bilbao

THE DREAM of JAVIER REVERTE The dream of Ramón Bilbao JAVIER REVERTE This book is not for sale. LEGAL NOTICE: All rights reserved. Except as specifically agreed in writing, and subject to the civil or criminal actions and the corresponding compensation for damages, the following acts are prohibited: (1) the copyright work may not be reproduced, distributed, communicated to the public, or transformed, in relation to the work as a whole or any part of it, either directly or indirectly; (2) the protected design may not be used by any third party; such use shall cover, in particular, the making, offering, putting on the market, importing, exporting, or using of a product in which the design is incorporated or to which it is applied, or stocking such a product for those purposes. PUBLISHED BY: Ramón Bilbao Winery. PUBLISHER: Ramón Bilbao Winery. EDITORIAL TEAM: Carmen Giné, Rodolfo Bastida, Carmen Bielsa and Clara Isabel Haba. AUTHOR: Javier Reverte. COORDINATION: Ramón Bilbao Winery Marketing Team. ART, LAYOUT AND FRONT COVER: Mi Abuela No Lo Entiende. ILLUSTRATIONS: Alex Ferreiro. DOCUMENTALIST: José Luis Gómez Urdáñez. © Javier Reverte © Bodegas Ramón Bilbao S.A. 2018 Avda Santo Domingo, 34 36200 – Haro (La Rioja) FIRST EDITION: JUNIO 2018. ISBN: 13-978-84-09-01944-1. LEGAL DEPOSIT: LR-619-2018. PRINTED IN SPAIN Foreword and acknowledgements RODOLFO BASTIDA Bringing together in this small book you are currently holding elements and words such as "legend", "entrepreneur", "dreams", history", "avant-garde", "exploration" or “wine” has been no easy task. This project is the culmination of months of hard work involving over a dozen people which has finally seen the light of day. -

The Piano Compositional Style of Lucrecia Roces Kasilag D.M.A. Document

THE PIANO COMPOSITIONAL STYLE OF LUCRECIA ROCES KASILAG D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Caroline Besana Salido, B.M., M.M. ***** The Ohio State University 2002 Document Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Glaser, Adviser Professor Arved Ashby Professor Kenneth Williams _______________ Document Adviser School of Music Copyright by Caroline Besana Salido 2002 ABSTRACT Often alluded to as the “First Lady of Philippine Music,” Lucrecia “King” Roces Kasilag, born in San Fernando, La Union, Philippines, on August 31, 1918, holds numerous national and international leadership roles as composer, educator, administrator, and researcher. Kasilag has composed more than 250 works covering most genres including orchestra, chamber, organ, piano, vocal, sacred, operetta, dance, theatre, electronic and incidental music. She is a nationally acclaimed composer and artist in the Philippines. However, most of her works are largely unpublished and difficult to retrieve for use in the academic, as well as in the performance community. Therefore, her contributions are not well known in the Western world to the degree they deserve. This document intends to provide a brief historical background of Philippine music, a biography of Kasilag describing her work and accomplishments, a list of her compositions and her contributions as a composer in ii today’s musical world. The writer will present detailed analyses of selected piano works for their sound, texture, harmony, melody, rhythm and form. The writer will also examine Western and Eastern influences within these piano works, reflecting Kasilag’s classic and romantic orientation with some use of twentieth-century techniques. -

Philippine Dances

PHILIPPINE DANCES Filipino has boundless passion for dance. Traditional dances show influences of the Malay, Spanish, and Muslim. Native dances depict different moods of the culture and beliefs, tribal rites or sacrifice, native feast and festivals, seek deliverance from pestilence, flirtation and courtship, planting and harvesting. Philippines dances were performed by famed dance troupe such as the Bayanihan, the Barangay, Kaanyag Filipinas and the Filipinescas or Karilagan. These dance troupes have performed around the world exhibiting the dances of our country. The more popular dances are featured here. This is called Singkil, a Royal Muslim dance. Muslim are native who originally come from the Middle East. This well-known dance portray Filipino-Muslims courtship. This dance is called Pandango Sa Ilaw, "dance with lights". The dancers move gracefully with little cups of lights on their head and held on back of their fingers. This popular dance is of Malays' influence. The Filipinos love to celebrate Fiestas, wherein people feasted the whole day with lots of food, dances, laughter and games celebrating the town's patron saints. This picture is called Palaro or Palo Sebo, a game where the boys were made to climb a greasy pole at the end of which is a pot of gold. Whoever succeeds get the gold and share it with the girl he got as partner. This is the most beautiful dance called Tinikling, "bamboo or heron" dance of Malay influence. A heron is a wading bird with long legs, neck and bill. The dancers will dance around the bamboo gracefully, trying to dance according to the rhythm of the beatings of the bamboo. -

The Mammals of Palawan Island, Philippines

PROCEEDINGS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON 117(3):271–302. 2004. The mammals of Palawan Island, Philippines Jacob A. Esselstyn, Peter Widmann, and Lawrence R. Heaney (JAE) Palawan Council for Sustainable Development, P.O. Box 45, Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines (present address: Natural History Museum, 1345 Jayhawk Blvd., Lawrence, KS 66045, U.S.A.) (PW) Katala Foundation, P.O. Box 390, Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines; (LRH) Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605 U.S.A. Abstract.—The mammal fauna of Palawan Island, Philippines is here doc- umented to include 58 native species plus four non-native species, with native species in the families Soricidae (2 species), Tupaiidae (1), Pteropodidae (6), Emballonuridae (2), Megadermatidae (1), Rhinolophidae (8), Vespertilionidae (15), Molossidae (2), Cercopithecidae (1), Manidae (1), Sciuridae (4), Muridae (6), Hystricidae (1), Felidae (1), Mustelidae (2), Herpestidae (1), Viverridae (3), and Suidae (1). Eight of these species, all microchiropteran bats, are here reported from Palawan Island for the first time (Rhinolophus arcuatus, R. ma- crotis, Miniopterus australis, M. schreibersi, and M. tristis), and three (Rhin- olophus cf. borneensis, R. creaghi, and Murina cf. tubinaris) are also the first reports from the Philippine Islands. One species previously reported from Pa- lawan (Hipposideros bicolor)isremoved from the list of species based on re- identificaiton as H. ater, and one subspecies (Rhinolophus anderseni aequalis Allen 1922) is placed as a junior synonym of R. acuminatus. Thirteen species (22% of the total, and 54% of the 24 native non-flying species) are endemic to the Palawan faunal region; 12 of these are non-flying species most closely related to species on the Sunda Shelf of Southeast Asia, and only one, the only bat among them (Acerodon leucotis), is most closely related to a species en- demic to the oceanic portion of the Philippines. -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS -

HOPE and SECURITY Through S&T

PCAARRD 20 ANNUAL 20 REPORT Bringing HOPE AND SECURITY Through S&T DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY (DOST) PHILIPPINE COUNCIL FOR AGRICULTURE, AQUATIC AND NATURAL RESOURCES RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT (PCAARRD) About DOST-PCAARRD The Philippine Council for higher education institutions involved regional, and national organizations Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural in crops, livestock, forestry, fisheries, and funding institutions for joint R&D, Resources Research and Development soil and water, mineral resources, human resource development and (PCAARRD) is one of the sectoral and socio-economic research and training, technical assistance, and councils under the Department of development (R&D). In 1987, the exchange of scientists, information, Science and Technology (DOST). It Council was renamed the Philippine and technologies. The Council is was formed through the consolidation Council for Agriculture, Forestry implementing its program primarily of the Philippine Council for and Natural Resources Research through its regional consortia, which Agriculture, Forestry and Natural and Development but retained the are located all over the country. Resources Research and Development acronym PCARRD. On January 30 of It also supports the National (PCARRD) and the Philippine Council the same year, the Philippine Council Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural for Aquatic and Marine Research and for Aquatic and Marine Research and Resources Research and Development Development (PCAMRD) on June 22, Development (PCAMRD) was created Network (NAARRDN) composed of 2011 pursuant to Executive Order from the Fisheries Research Division national multi- and single-commodity No. 366. of PCARRD with functions focused on and regional R&D centers, cooperating Originally established in November aquatic and marine sectors. stations, and specialized agencies. -

History of Clark Air Base 1 History of Clark Air Base

History of Clark Air Base 1 History of Clark Air Base The history of Clark Air Base, Philippines dates back to the late 19th century when it was settled by Filipino military forces. The United States established a presence at the turn of the century. The Americans first come to Angeles In the late 19th century, a British company working under contract to the colonial Spanish administration, had completed the Manila-Dagupan Railroad and at the time of America's victory over the Spanish, this still represented the best means of transportation in Luzon. Following the incidents that led to the beginning of US-Philippine hostilities and Emilio Aguinaldo's withdrawal to the north from Manila, the American forces attempted to seize control of this valuable line of communication. The Philippine Army, numbering about 15,000, was just as determined to defend this vital link, 1941: Clark Field in Angeles, Pampanga looking westward. In the upper left center, abutting the foothills of the and during 1899, fought a series of unsuccessful battles with Zambales Mountains, lies Fort Stotsenburg. The rectangular, US forces. tree-lined area is the parade ground. On March 17, 1899, General Aguinaldo moved the seat of his government from Nueva Ecija to the town of Angeles, which lay astride the Manila-Dagupan Railroad, and there celebrated the first anniversary of the Philippine Republic, on June 12, 1899. The Republican government remained hard-pressed by the American advance, and in July, Aguinaldo moved his government again, this time, to the town of Tarlac, further to the north. The battle for Angeles began on August 13, 1899 and lasted for three days. -

Hats Discovery Kit Collection

Virtual Discovery Kit. Hats. grpm.org Hats and headwear have been worn for centuries by people around the world to serve a variety of purposes, cultural traditions and religious practices. This resource provides tools and activities for investigating a number of hats in the Grand Rapid Public Museum’s Collections. Explore the hats in the GRPM digital Collections at https://grpmcollections.org/Detail/occurrences/328 then have fun with these activities. Historical Evidence of Hats and Headwear Historians and archeologists find that people wore hats and headwear dating back thousands of years ago. 5,000 year old hat-wearer • In the 1990s, a mummified body was found in the ice of the Italian Alps. It was the body of an adult male that scientists named Otzi the Iceman. • Otzi was found wearing a cap made from the hide of a brown bear. 2 This discovery shows a hat being worn almost 5,300 years ago! 1 4,000 year old Egyptian hats • Evidence of ancient Egyptians wearing cone-shaped objects on their head have been found in artwork and images from tombs, papyri (paper) and coffins. These hats seem to have been part of rituals or ceremonies.3 • Archeologists have recently found mummies buried with cone-shaped 4 hats. Research concluded that the hats were made from beeswax. 5 Red liberty caps have long symbolized freedom • This style of liberty cap, also known as a Phrygian Cap, traces its history back to the ancient kingdom of Phrygia. • In ancient Rome, these hats symbolized freedom and were given to freed slaves in a ceremony announcing their new status.6 7 • These red caps were used in the late 1700s in France, during the French Revolution. -

25Th Annual Gala & 16Th Induction Ball

FILIPINO-AMERICAN 25TH ANNUAL GALA ASSOCIATION OF 24TH ANNIVERSARY GREATER COLUMBIACOLUMBIA, SC 16TH INDUCTION BALL SEPTEMBER 19, 2015 ~~~ COLUMBIA MARRIOTT HOTEL FAAGC Outgoing 2014-2015 Executive Board President Cecille Jacobsen 1st VP Faye Colley 2nd VP Eric Sosa Secretary Jocelyn Locke Asst. Secretary Sheena Shearer Treasurer Priscila Ramirez Asst. Treasurer Miriam Eschenfelder Board Member Edith Alston Board Member Tess Hill Board Member Carlos Arevalo Board Member Peter Liunoras Board Member Alma Robichaud President First Vice-President Second Vice-President Treasurer CECILLE JACOBSEN TESS HILL ALAN MATIENZO MIRIAM ESCHENFELDER Secretary Assistant Treasurer Assistant Secretary Executive Board Member REYNA FUNDERBURK ANNA TEMPLES DORIS MATOS CARLOS AREVALO Executive Board Member Executive Board Member Executive Board Member Executive Board Member 2015-2017 EXECUTIVE BOARD FILIPINO-AMERICAN Association of Greater Columbia, SC SC Columbia, of Greater Association FILIPINO-AMERICAN AL COCKEREL GLENN DE GUZMAN PETER LIUNORAS JAMES ORLICK “Together We P.O. Box 24112, Columbia, SC 29224 e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Make A Difference” website: www.FilAmSC.org F I L I P I N O - A M E R I C A N Association of Greater Columbia, SC 16th Induction Ball 24TH ANNIVERSARY 25th Annual Gala Saturday, September 19, 2015 Columbia Marriott Hotel, Columbia, SC 6:00 Reception (cash cocktails at the Sports Bar near the ballroom) 6:30 National Anthems: United States . Leila Cockerel Philippines . Hannelore Peña Ignacio (FAAGC President, 2001-2003; Board Member, 2015-17) Invocation . Peter Liunoras Welcome Remarks . Emcees . Dolly Ritchie & James Orlick Recognition of Attendees FAAGC Member FAAGC Executive Board Member, 2015-2017 Induction of FAAGC 2015-2017 Officers Eric Sosa (FAAGC 2nd Vice-President, 2013-2015) Opening Remarks . -

Aes with CAO.Xlsx

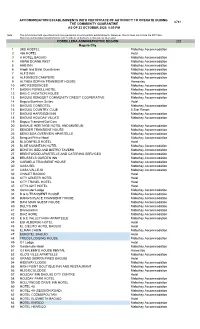

ACCOMMODATION ESTABLISHMENTS WITH CERTIFICATE OF AUTHORITY TO OPERATE DURING 6781 THE COMMUNITY QUARANTINE AS OF 23 OCTOBER 2020, 5:00 PM Note: The list includes both operational and non-operational accommodation establishments. Moreover, this list does not include the DOT Star- Rated Accommodation Establishments with Certificate of Authority to Operate for Staycation. CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION 203 Baguio City 1 3BU HOSTEL Mabuhay Accommodation 2 456 HOTEL Hotel 3 A HOTEL BAGUIO Mabuhay Accommodation 4 ABWE DOANE REST Mabuhay Accommodation 5 AHB INN Mabuhay Accommodation 6 Aleph and Dalet Guesthaven Mabuhay Accommodation 7 ALF'S INN Mabuhay Accommodation 8 ALFONSO'S CAMPSITE Mabuhay Accommodation 9 ALTHEA SOPHIA TRANSIENT HOUSE Homestay 10 ARC RESIDENCES Mabuhay Accommodation 11 BADEN POWELL HOTEL Mabuhay Accommodation 12 BAG-C VACATION HOUSE Mabuhay Accommodation 13 BAGUIO BENGUET COMMUNITY CREDIT COOPERATIVE Mabuhay Accommodation 14 Baguio Burnham Suites Hotel 15 BAGUIO CONDOTEL Mabuhay Accommodation 16 BAGUIO COUNTRY CLUB 5 Star Resort 17 BAGUIO HARRISON INN Mabuhay Accommodation 18 BAGUIO HOLIDAY VILLA'S Mabuhay Accommodation 19 Baguio Transient Dot Com 20 BANAUE HERITAGE HOTEL AND MUSEUM Mabuhay Accommodation 21 BENDER TRANSIENT HOUSE Mabuhay Accommodation 22 BENG BOA OVERVIEW APARTELLE Mabuhay Accommodation 23 Benguet Prime Hotel Mabuhay Accommodation 24 BLOOMFIELD HOTEL Hotel 25 BLUE MOUNTAIN HOTEL Mabuhay Accommodation 26 BONTOC BED AND BISTRO TAVERN Mabuhay Accommodation 27 BRENTWOOD APARTELLE AND CATERING SERVICES Mabuhay -

Universidad Técnica Del Norte Facultad De Ingeniería En Ciencias Aplicadas Carrera De Ingeniería En Diseño Textil Y Modas

UNIVERSIDAD TÉCNICA DEL NORTE FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA EN CIENCIAS APLICADAS CARRERA DE INGENIERÍA EN DISEÑO TEXTIL Y MODAS TRABAJO DE GRADO PREVIO A LA OBTENCIÓN DEL TÍTULO DE INGENIERA EN DISEÑO TEXTIL Y MODAS TEMA: INVESTIGACIÓN Y DESARROLLO DE UN NO TEJIDO A PARTIR DEL ENFIELTRAMIENTO DE ALGODÓN CON PELOS CANINOS Y SU APLICACIÓN EN SOMBREROS PARA DAMAS AUTORA: GRISELDA NOEMÍ ANGAMARCA CUASQUI DIRECTORA DE TESIS: ING. SANDRA ELIZABETH ÁLVAREZ RAMOS Ibarra – Ecuador 2017 UNIVERSIDAD TÉCNICA DEL NORTE BIBLIOTECA UNIVERSITARIA AUTORIZACIÓN DE USO Y PUBLICACIÓN A FAVOR DE LA UNIVERSIDAD TÉCNICA DEL NORTE 1. IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LA OBRA La Universidad Técnica del Norte dentro del proyecto Repositorio Digital Institucional determina la necesidad de disponer los textos completos de forma digital con la finalidad de apoyar los procesos de investigación, docencia y extensión de la Universidad. Por medio del presente documento dejo sentada mi voluntad de participar en este proyecto, para lo cual pongo a disposición la siguiente investigación: DATOS DEL CONTACTO CEDULA DE IDENTIDAD 1003421482 APELLIDOS Y NOMBRES ANGAMARCA CUASQUI GRISELDA NOEMÍ DIRECCIÓN SAN FRANCISCO DEL TEJAR EMAIL [email protected] TELÉFONO FIJO 062604427 TELÉFONO MÓVIL 0992515470 DATOS DE LA OBRA “INVESTIGACIÓN Y DESARROLLO DE UN NO TÍTULO TEJIDO A PARTIR DEL ENFIELTRAMIENTO DE ALGODÓN CON PELOS CANINOS Y SU APLICACIÓN EN SOMBREROS PARA DAMAS” AUTOR ANGAMARCA CUASQUI GRISELDA NOEMÍ FECHA JUNIO 2017 PROGRAMA PREGRADO TÍTULO POR EL QUE INGENIERÍA EN DISEÑO TEXTIL Y MODAS OPTA