Speculations on History's Futures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deconstructing Windhoek: the Urban Morphology of a Post-Apartheid City

No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 Working Paper No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Contents PREFACE 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 2. WINDHOEK CONTEXTUALISED ....................................................................... 2 2.1 Colonising the City ......................................................................................... 3 2.2 The Apartheid Legacy in an Independent Windhoek ..................................... 7 2.2.1 "People There Don't Even Know What Poverty Is" .............................. 8 2.2.2 "They Have a Different Culture and Lifestyle" ...................................... 10 3. ON SEGREGATION AND EXCLUSION: A WINDHOEK PROBLEMATIC ........ 11 3.1 Re-Segregating Windhoek ............................................................................. 12 3.2 Race vs. Socio-Economics: Two Sides of the Segragation Coin ................... 13 3.3 Problematising De/Segregation ...................................................................... 16 3.3.1 Segregation and the Excluders ............................................................. 16 3.3.2 Segregation and the Excluded: Beyond Desegregation ....................... 17 4. SUBURBANISING WINDHOEK: TOWARDS GREATER INTEGRATION? ....... 19 4.1 The Municipality's -

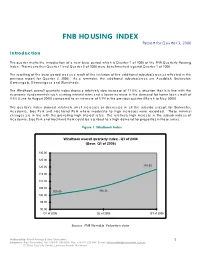

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006 Introduction This quarter marks the introduction of a new base period which is Quarter 1 of 2006 of the FNB Quarterly Housing Index. This means that Quarter 2 and Quarter 3 of 2006 were benchmarked against Quarter 1 of 2006. The resetting of the base period was as a result of the inclusion of five additional suburbs/areas as reflected in the previous report for Quarter 2, 2006. As a reminder, the additional suburbs/areas are Auasblick, Brakwater, Goreangab, Okuryangava and Wanaheda. The Windhoek overall quarterly index shows a relatively slow increase of 11.6%, a situation that is in line with the economic fundamentals such as rising interest rates and a lower increase in the demand for home loan credit of 3.6% (June to August 2006) compared to an increase of 5.9% in the previous quarter (March to May 2006). This quarter’s index showed relatively small increases or decreases in all the suburbs except for Brakwater, Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park where moderate to high increases were recorded. These minimal changes are in line with the prevailing high interest rates. The relatively high increase in the suburb indices of Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park could be ascribed to a high demand for properties in these areas. Figure 1: Windhoek Index Windhoek overall quarterly index - Q3 of 2006 (Base: Q1 of 2006) 130.00 125.00 120.00 118.55 115.00 110.00 105.00 100.00 106.22 100.00 95.00 90.00 Q1 of 2006 Q2 of 2006 Q3 of 2006 Source: FNB Namibia Valuation data Authored by: Martin Mwinga & Alex Shimuafeni 1 Enquiries: Alex Shimuafeni, Tel: +264 61 2992890, Fax: +264 61 225 994, E-mail: [email protected] 5th Floor, First City Centre, Levinson Arcade, Windhoek Brakwater recorded an extraordinary high quarterly increase of 72% from Quarter 2. -

Touring Katutura! : Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism In

Universität Potsdam Malte Steinbrink | Michael Buning | Martin Legant | Berenike Schauwinhold | Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA ! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Potsdamer Geographische Praxis Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Malte Steinbrink|Michael Buning|Martin Legant| Berenike Schauwinhold |Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de/ abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2016 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: -2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Die Schriftenreihe Potsdamer Geographische Praxis wird herausgegeben vom Institut für Geographie der Universität Potsdam. ISSN (print) 2194-1599 ISSN (online) 2194-1602 Das Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Gestaltung: André Kadanik, Berlin Satz: Ute Dolezal Titelfoto: Roman Behrens Druck: docupoint GmbH Magdeburg ISBN 978-3-86956-384-8 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam: URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 11 1.1 Background of the study: -

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location Henning Melber1 Abstract The Windhoek Old Location refers to what had been the South West African capital’s Main Lo- cation for the majority of black and so-called Colored people from the early 20th century until 1960. Their forced removal to the newly established township Katutura, initiated during the late 1950s, provoked resistance, popular demonstrations and escalated into violent clashes between the residents and the police. These resulted in the killing and wounding of many people on 10 December 1959. The Old Location since became a synonym for African unity in the face of the divisions imposed by apartheid. Based on hitherto unpublished archival documents, this article contributes to a not yet exist- ing social history of the Old Location during the 1950s. It reconstructs aspects of the daily life among the residents in at that time the biggest urban settlement among the colonized majority in South West Africa. It revisits and portraits a community, which among former residents evokes positive memories compared with the imposed new life in Katutura and thereby also contributed to a post-colonial heroic narrative, which integrates the resistance in the Old Location into the patriotic history of the anti-colonial liberation movement in government since Independence. O Lord, help us who roam about. Help us who have been placed in Africa and have no dwelling place of our own. Give us back a dwelling place.2 The Old Location was the Main Location for most of the so-called non-white residents of Wind- hoek from the early 20th century until 1960, while a much smaller location also existed until 1961 in Klein Windhoek. -

Public Notice Electoral Commission of Namibia

The Electoral Commission of Namibia herewith publishes the names of the Political Party lists of Candidates for the National Assembly elections which will be gazzetted on 7th November 2019. If any person’s name appears on a list without their consent, they can approach the Commission in writing in terms of Section 78 (2) of the Electoral Act, No. 5 of 2014. In such cases the Electoral Act of 2014 empowers the Commission to make withdrawals or removals of candidates after gazetting by publishing an amended notice. NATIONAL ASSEMBY ELECTIONS POLITICAL PARTIES CANDIDATE LIST 2019 PUBLIC NOTICE ELECTORAL COMMISSION OF NAMIBIA NOTIFICATION OF REGISTERED POLITICAL PARTIES AND LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR REGISTERED POLITICAL PARTIES: GENERAL ELECTION FOR ELECTION OF MEMBERS OF NATIONAL ASSEMBLY: ELECTORAL ACT, 2014 In terms of section 78(1) of the Electoral Act, 2014 (Act no. 5 of 2014), the public is herewith notified that for the purpose of the general election for the election of members of the National Assembly on 27 November 2019 – (a) The names of all registered political parties partaking in the general election for the election of the members of the National Assembly are set out in Schedule 1; (b) The list of candidates of each political party referred to in paragraph (a), as drawn up by the political parties and submitted in terms of section 77 of that Act for the election concerned is set out in Schedule 2; and (c) The persons whose names appear on that list referred to in paragraph (b) have been duly nominated as candidates of the political party concerned for the election. -

Biography-Sam-Nujoma-332D79.Pdf

BIOGRAPHY Name: Sam Nujoma Date of Birth: 12 May 1929 Place of Birth: Etunda-village, Ongandjera district, North- Western Namibia – (Present Omusati Region) Parents: Father: Daniel Uutoni Nujoma - (subsistence farmer) Mother: Helvi Mpingana Kondombolo- (subsistence farmer) Children: 6 boys and 4 girls. From Childhood: Like all boys of those days, looked after his parents’ cattle, as well as assisting them at home in general work, including in the cultivation of land. Qualifications: Attended Primary School at Okahao Finnish Mission School 1937-1945; In the year 1946, Dr. Nujoma moved to the coastal town of Walvisbay to live with his aunt Gebhart Nandjule, where in 1947 at the age of 17 he began his first employment at a general store for a monthly salary of 10 Shillings. It was in Walvis Bay that he got exposed to modern world politics by meeting soldiers from Argentina, Norway and other parts of Europe who had been brought there during World War II. Soon after, at the beginning of 1949 Dr. Nujoma went to live in Windhoek with his uncle Hiskia Kondombolo. In Windhoek he started working for the South African Railways and attended adult night school at St. Barnabas in the Windhoek Old Location. He further studied for his Junior Certificate through correspondence at the Trans-Africa Correspondence College in South Africa. Marital Status: On 6 May 1956, Dr Nujoma got married to Kovambo Theopoldine Katjimune. They were blessed with 4 children: Utoni Daniel (1952), John Ndeshipanda (1955), Sakaria Nefungo (1957) and Nelago (1959), who sadly passed away at the age of 18 months, while Dr. -

Namibia After 26 Years

On the other side of the picture are elements in the police and to devote their energies instead to making the force who are not neutral, or are trigger-happy, or are country ungovernable. Such lessons are more easily both. They may well be covert rightwingers trying to learnt than forgotten. Ungovernability down there, where sabotage reform. Other rightwingers seem set on making the necklace lies in wait for non-conformists, and the the mining town of Welkom a no-go area for Blacks. They incentive to learn has been largely lost, presents the ANC may not stop there. with a major problem. For Mr De Klerk it certainly makes his task of persuading Whites to accept a future in a non- More disturbing than any of this has been the resurrection racial democracy a thousand times more difficult. of the dreaded "necklace", surely one of the most despicable and dehumanising methods over conceived So what has to be done if what is threatening to become a for dealing with people you think might not be on your lost generation is to be saved, and if something like the side. The leaders of the liberation movement who failed, Namibian miracle is to be made to happen here? for whatever reason, to put a stop to this ghastly practice when it first reared its head amongst their supporters all People need to be given something they feel is important those years ago, may well live to rue that day. Only and constructive to do. What better than building a new Desmond Tutu and a few other brave individuals ever society? risked their own lives to stop it. -

The Transformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 The Transformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia Katherine Caufield Arnold College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Arnold, Katherine Caufield, "The rT ansformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 251. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/251 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Introduction Although we kept the fire alive, I well remember somebody telling me once, “We have been waiting for the coming of our Lord. But He is not coming. So we will wait forever for the liberation of Namibia.” I told him, “For sure, the Lord will come, and Namibia will be free.” -Pastor Zephania Kameeta, 1989 On June 30, 1971, risking persecution and death, the African leaders of the two largest Lutheran churches in Namibia1 issued a scathing “Open Letter” to the Prime Minister of South Africa, condemning both South Africa’s illegal occupation of Namibia and its implementation of a vicious apartheid system. It was the first time a church in Namibia had come out publicly against the South African government, and after the publication of the “Open Letter,” Anglican and Roman Catholic churches in Namibia reacted with solidarity. -

Public Perception of Windhoek's Drinking Water and Its Sustainable

Public Perception of Windhoek’s Drinking Water and its Sustainable Future A detailed analysis of the public perception of water reclamation in Windhoek, Namibia By: Michael Boucher Tayeisha Jackson Isabella Mendoza Kelsey Snyder IQP: ULB-NAM1 Division: 41 PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF WINDHOEK’S DRINKING WATER AND ITS SUSTAINABLE FUTURE A DETAILED ANALYSIS OF THE PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF WATER RECLAMATION IN WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA AN INTERACTIVE QUALIFYING PROJECT REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE SPONSORING AGENCY: Department of Infrastructure, Water and Waste Management The City of Windhoek SUBMITTED TO: On-Site Liaison: Ferdi Brinkman, Chief Engineer Project Advisor: Ulrike Brisson, WPI Professor Project Co-advisor: Ingrid Shockey, WPI Professor SUBMITTED BY: ____________________________ Michael Boucher ____________________________ Tayeisha Jackson ____________________________ Isabella Mendoza ____________________________ Kelsey Snyder Abstract Due to ongoing water shortages and a swiftly growing population, the City of Windhoek must assess its water system for future demand. Our goal was to follow up on a previous study to determine the public perception of the treatment process and the water quality. The broader sample portrayed a lack of awareness of this process and its end product. We recommend the City of Windhoek develop educational campaigns that inform its citizens about the water reclamation process and its benefits. i Executive Summary Introduction and Background Namibia is among the most arid countries in southern Africa. Though it receives an average of 360mm of rainfall each year, 83 percent of this water evaporates immediately after rainfall. Another 14 percent goes towards vegetation, and 1 percent supplies the ground water in the region, thus leaving merely 2 percent for surface use. -

S/87%' 6 August 1968 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH

UNITED NATIO Distr . GENERA1 S/87%' 6 August 1968 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH LETTER DATED 5 AUGTJST 1968 FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED NATIONS COUNCIL FOR NAMIBIA ADDRESSED TO 'THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL I have the honour to bring to your attention a message received by the Secretary-General from Mr, Clemens Kapuuo of Windhoek, Namibia, on 24 July lsi'48, stating that non-white Namibians were being forcibly removed from their homes in Windhoek to the new segregated area of Katutura, and requesting the Secretary- General to convene a meeting of the Security Council to consider the matter. According to the message, the deadline for their removal is 31 August 1968, after which date they would not be allowed to continue to live in their present areas of residence. On the same date the Secretary-General transmitted the message in a letter to the United Nations Council for Namibia as he felt that the Council might wish to give the matter urgent attention. A copy of the letter is attached herewith (annex I). The Council considered the matter at its 34th and 35th meetings, held on 25 July 1968 and 5 August 1968 respectively. According to information available to the Council (annex II), the question of the removal of non-whites from their homes in Windhoek to the segregated area 0-P IChtutura first arose in 1959 and was the subject of General Assembly resolution 1567 (XV) of 18 December 1960. At the aforementioned meetings, the Council concluded that the recent actions of the South African Government constitute further evidence of South Africa's continuing defiance of the authority of the United Nations and a further violation of General Assembly resolutions 2145 (XXI), 2248 (S-V), 2325 (XXII) and 2372 (XXII). -

Hans Beukes, Long Road to Liberation. an Exiled Namibian

Journal of Namibian Studies, 23 (2018): 101 – 123 ISSN: 2197-5523 (online) Thinking and writing liberation politics – a review article of: Hans Beukes, Long Road to Liberation . An Exiled Namibian Activist’s Perspective André du Pisani* Abstract Thinking and Writing Liberation Politics is a review article of: Hans Beukes, Long Road to Liberation. An Exiled Namibian Activist’s Perspective; with an introduction by Professor Mburumba Kerina, Johannesburg, Porcupine Press, 2014. 376 pages, appendices, photographs, index of names. ISBN: 978-1-920609-71-9. The article argues that Long Road to Liberation , being a rich, diverse, uneven memoir of an exiled Namibian activist, offers a sobering and critical account of the limits of liberation politics, of the legacies of a protracted struggle to bring Namibia to independence and of the imprint the struggle left on the political terrain of the independent state. But, it remains the perspective of an individual activist, who on account of his personal experiences and long absence from the country of his birth, at times, paints a fairly superficial picture of many internal events in the country. The protracted diplomatic-, political- and liberation struggle that culminated in the independence of Namibia in March 1990, has attracted a crop of publications written from different perspectives. This has produced many competing narratives. It would be fair to say that many of the books published over the last decade or so, differ in their range, quality and usefulness to researchers and the reading public at large. This observation also holds for memoirs, a genre of writing that is most demanding, for it requires brutal honesty, the ability to truthfully recall and engage with events that can traverse several decades. -

UNU/UNESCO 2009 International

UNU/UNESCO International Conference September 28 & 29, 2009 • Tokyo, Japan www.unu.edu/globalization Africa and Globalization Learning from the past, enabling a better future Presenter & Panellist biograPhies Walid MahMoud abdelnasser Ambassador of the Arab Republic of Egypt to Japan Walid Mahmoud Abdelnasser served as chief of cabinet to the Egyptian minister of foreign affairs (2001–2002) and subsequently at the Egyptian Embassy in Washington D.C. (2002–2006). There- after he was director of the Diplomatic Institute in Cairo (2006–2007). He was seconded to the United Nations from 1992 to 1999. He is the author of seventeen books in Arabic, four in English, and has contributed to numerous publications in Arabic, French, English and Japanese. He is a member of the Egyptian Council of Foreign Relations, the Egyptian Writers’ Association, and the editorial board of the journal Beyond published by the association of former Egyptian employees at the United Nations. He holds a PhD in political science and a “license en droit”. CleMent e. adibe Associate Professor of Political Science, DePaul University, Chicago Clement Eme Adibe is an associate professor of political science at DePaul University, Chicago. He obtained his PhD in political studies from Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, in 1995 and was the Killam post-doctoral fellow at Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada, in 1995 and 1996. He served as a researcher at the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research in Geneva, Switzerland in 1995. He was a research fellow at the Center for International Affairs, Harvard University (1992–1993); Watson Institute for International Studies, Brown University (1993–1994); Legon Center for International Affairs, University of Ghana, Legon (1993); Queen’s Center for In- ternational Relations, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada (1994); and the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo, Norway (2001–2002).