Gonçalo Piolti Cholant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 16-17, 2018 Show Hours 10:00-4:00

June 16-17, 2018 Show Hours 10:00-4:00 This Vintage Motoryacht Show is produced by the Classic Yacht Association. The CYA was organized in 1969 to promote and encourage the preservation, restoration and maintenance of fine old power-driven craft. Membership information is available at the gangway. Visit our website at classicyacht.org The following vessels are on display today. A “People’s Choice” ballot is available with this program, and we invite you to vote for your favorite yacht by dropping off your ballot in the container at the gangway on your way out. If the “Welcome Aboard” sign is posted, vessels may be boarded with the owner’s permission. Please wear soft-soled shoes. Boarding vessels is done at own risk. This year’s Marque Class celebrates vessels built by the Blanchard Boat Company, which crafted hundreds of wooden boats on Seattle’s Lake Union. Look for these unique classics on Docks A and B. * * * * * ADAGIO Adagio was built in New York using Richardson’s WWII plywood technology, touted as the “Cruiser of Tomorrow”, and the hull was designed by Sparkman and Stephens in a 1943 contest. She was shipped to Puget Sound, which may account for her longevity. The Twin Crusader engines were replaced with Gray Marines in 1965. Minor upgrades have been done to the interior and systems, but her basic Sedan Cruiser design is retained. Home Port is Decatur Island where the owner’s cabin is, and her covered moorage in Portage Bay helps keep her preserved.. ALOHA A 40’ 1962 Owens Tahitian, Aloha was sold new in Seattle, mooring at the Seattle Yacht Club for 39 years, 1962- 2001. -

A History of the Missionary Activities of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in India, 1849-1856

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1964 A History of the Missionary Activities of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in India, 1849-1856 R. Lanier Britsch Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Britsch, R. Lanier, "A History of the Missionary Activities of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in India, 1849-1856" (1964). Theses and Dissertations. 4556. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4556 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 0 there is nothing more heroic in our church annals than the labors and sufferings of these brethren of the mission ta india Bbo Hho roberts ofooroC riftr vat 0 IV af 7777- 73 1 101.0to W W A HISTORY OF THE missionary activities OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTERDAYLATTER DAY SAINTS IN INDIA 184918561849 1856 A thesis presented to the department of history brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts by ralph lanier britschbrits oh july 1964 PREFACE AND acknowledgementsACKNOWLEDGEMENTS the continent of asia is vast and heavily populated A greater understanding of this important -

Ralph Fitch, England's Pioneer to India and Burma

tn^ W> a-. RALPH FITCH QUEEN ELIZABETH AND HER COUNSELLORS RALPH FITCH flMoneet; to Snfcta anD 3Burma HIS COMPANIONS AND CONTEMPORARIES WITH HIS REMARKABLE NARRATIVE TOLD IN HIS OWN WORDS + -i- BY J. HORTON RYLEY Member of the Hnkhiyt Society LONDON T. FISHER UNWIN PATERNOSTER SQUARE 1899 reserved.'} PREFACE much has been written of recent years of the SOhistory of what is generally known as the East India Company, and so much interesting matter has of late been brought to light from its earliest records, that it seems strange that the first successful English expedition to discover the Indian trade should have been, comparatively speaking, overlooked. Before the first East India Company was formed the Levant Com- pany lived and flourished, largely through the efforts of two London citizens. Sir Edward Osborne, sometime Lord Mayor, and Master Richard Staper, merchant. To these men and their colleagues we owe the incep- tion of our great Eastern enterprise. To the fact that among them there were those who were daring enough, and intelligent enough, to carry their extra- ordinary programme into effect we owe our appear- ance as competitors in the Indian seas almost simultaneously with the Dutch. The beginning of our trade with the East Indies is generally dated from the first voyage of James Lancaster, who sailed from Plymouth in 1591. But, great as his achievement was, , **** 513241 vi PREFACE and immediately pregnant with consequences of a permanent character, he was not the first Englishman to reach India, nor even the first to return with a valuable store of commercial information. -

Get on Board! Get 7-Letter Bingos on Your Board About TRANSPORTATION, TRANSIT, TRAVEL Compiled by Jacob Cohen, Asheville Scrabble Club

Get on Board! Get 7-letter bingos on your board about TRANSPORTATION, TRANSIT, TRAVEL compiled by Jacob Cohen, Asheville Scrabble Club A 7s AERADIO AADEIOR Canadian radio service for pilots [n -S] AEROBAT AABEORT one that performs feats in aircraft [n -S] AILERON AEILNOR movable control surface on airplane wing [n -S] AIRBAGS AABGIRS AIRBAG, inflatable safety device in automobile [n] AIRBOAT AABIORT boat used in swampy areas [n -S] AIRCREW ACEIRRW crew of aircraft [n -S] AIRDROP ADIOPRR to drop from aircraft [v -PPED, -PPING, -S] AIRFARE AAEFIRR payment for travel by airplane [n -S] AIRFOIL AFIILOR part of aircraft designed to provide lift or control [n -S] AIRLIFT AFIILRT to transport by airplane [v -ED, -ING, -S] AIRMAIL AAIILMR to send mail by airplane [v -ED, -ING, -S] AIRPARK AAIKPRR small airport (tract of land maintained for landing and takeoff of aircraft) [n -S] AIRPORT AIOPRRT tract of land maintained for landing and takeoff of aircraft [n -S] AIRPOST AIOPRST system of conveying mail by airplane [n -S] AIRSHIP AHIIPRS lighter-than-air aircraft having propulsion and steering systems [n -s] AIRSHOW AHIORSW exhibition of aircraft stunts [n -S] AIRSICK ACIIKRS nauseated from flying in airplane [adj] AIRSIDE ADEIIRS side of airport terminal facing aircraft [n -S] AIRTRAM AAIMRRT aerial cable car [n -S] AIRVACS AACIRSV AIRVAC, evacuation by air ambulance [n] AIRWAYS AAIRSWY AIRWAY, passageway in which air circulates [n] ALAMEDA AAADELM shaded walkway [n -S] ALLIAKS AAIKLLS ALLIAK, Inuit sledge [n] AMBAGES AABEGMS AMBAGE, winding path -

Spell of Fate.Pdf

SPELL OF FATE BY MAYER ALAN BRENNER PROLOGUE UNTIE LEEN! AUNTIE LEEN! Look what I found!” Auntie Leen, also known as the Keeper of the Imperial “A Archives, raised her eyes above the lenses of her reading glasses as the three-year-old figure of her nephew skidded to an uncertain halt next to her desk. In the midst of a frenetic bustle of waving arms she could see that both hands were empty, and the pockets exhibited no more than their typical bulge. “Very well,” said Leen. “I’m looking. What are you hiding, and where are you hiding it?” He was tugging insistently at her hand. “Here! Come here!” Robin had been rummaging somewhere off in the back, playing hide- and-seek with himself among the uneven aisles and coating himself with his usual cloud of grime. With her free hand, Leen slid an acid-free marker into the ancient book and closed the crumbly cover, leaving it perched on the reading stand, and picked up her lantern. Although her work area was liberally furnished with candles, thus slowing the deterioration in her eyesight, the deeper reaches of the archive had only the illumination one brought to them. How had Robin been able to see whatever he’d discovered? As Robin trotted ahead of her off into the darkness, a blue glow spread out ahead of him, lighting his way through the crates and leaning piles of scrolls and books. Leen scowled to herself. She must be getting prematurely © 1990-2010 by Mayer Alan Brenner. First published by DAW Books, New York, NY, March, 1992. -

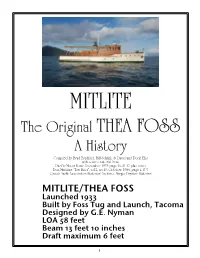

The Original THEA FOSS a History

MITLITE The Original THEA FOSS A History Compiled by Brad Bradford, Bill Schlink, & David and Dorin Ellis with source material from: Pacific Motor Boat; December 1933 page 16 & 17 plus cover Foss Maritime “Tow Bitts”; vol.2, no.10; October 1986; page 4 & 5 Classic Yacht Association Historical Archives, Margie Paynton Historian MITLITE/THEA FOSS Launched 1933 Built by Foss Tug and Launch, Tacoma Designed by G.E. Nyman LOA 58 feet Beam 13 feet 10 inches Draft maximum 6 feet 1 MITLITE HISTORY (Revised 9/27/2013) Launched in 1933, 58 foot long MITLITE is the original THEA FOSS. In late 1931, with a view of owner Henry Foss to hold Foss workmen on the job as much as possible during the depression, work was begun on the only yacht listed on the Foss History web site to be built by the Foss Tug and Launch Company works at Tacoma. When other work was a bit slack, work on THEA was resumed, thus assisting the owner in keeping the company’s well organized crew employed. Her lines were drawn by G.E. Nyman of Tacoma and her construction was under the supervision of Linas Berg. Hollow Tobin bronze wing shaped rudder and stream-line designed air-driven winch as well as all outer gear were cast by Tacoma Brass Company and finished by Fred Dravis of Hicks and Bull Company, Tacoma. All are still with the boat and functioning well. MITLITE (THEA FOSS) was originally powered with a 66hp Washington full Diesel and she was also equipped with an Atlas Imperial lighting outfit with a belt driven Westinghouse 32 volt generator on the main engine. -

Bresillac Souvenir Vol 3 ENG.Pdf

MARION BRESILLAC SOUVENIRS VOL 3 LE JOURNAL D'UN MISSIONNAIRE (1849 - 1854) S.M.A. 1991 Cum permissu superiorum Patrick J. Harrington, S.M.A., Superior General, Rome, 25th June, 1991 French edition prepared by an S.M.A. team Put into present-day English by Bob Hales, S.M.A The present digital edition was prepared with the kind assistance of Dolores McCrystal and Joan Quinn. Cover design by Ann McCarthy, Ballinadee PART I – THE LAST FlVE YEARS IN INDIA 1849 – Outnumbered 1041 1850 - Fight for a Solution or just get out? 1069 1851 - Ball now in Rome’s court. Ceylon 1095 1852 - Becoming morally untenable 1159 1853 - On the way out 1179 PART II - JOURNEY TO ROME AND PARIS 1209 Guide to Chapters and Sections 1439 FOREWORD Souvenirs 1 and 2 are based on Marion Bresillac's journal or his personal diary, but they include many longish reflections and letters added in 1855 when he was preparing his Indian memoirs for publication. (They also exclude some remarks which he considered too rough to print, or maybe unfair). The editing and amplifying job stopped suddenly when he had got to the last entry for 1848... Africa beckoned. And the next thing we hear, he is busy founding a new society (S.M.A.) and preparing to go to Dahomey. (The blue Diary 1856-1859 covers that period). Obviously, he had not much time to work on his journal after that. So what we have here in Souvenirs 3 is his "raw" Missionary Journal (1849-1854) without subtraction or addition. -

Atalaya Cabbala Kabbala Baccara Arabica Bacalao

ATALAYA ALBATAS MARACAS SARDANA YATAGAN MASALAS CABBAGE CARABIN BEADMAN CABBALA ATABALS MARASCA GALATEA HALAKAH SALAAMS CABBAGY COPAIBA SAMBAED KABBALA BALATAS MASCARA APANAGE HALAKHA LANTANA CABOMBA TAXICAB BANDEAU BACCARA ABOMASA CARAVAN ALTHAEA HALALAH PALAPAS GABBARD PAYBACK ABRADER ARABICA MASTABA CANASTA ANAEMIA HALAVAH ARRAYAL BEANBAG BARRACK ABRADES BACALAO BANANAS CANTATA AZALEAS HARIANA LAYAWAY BABESIA BACKSAW AUBADES CABALAS ARAROBA CARAPAX ANATASE APHASIA MANANAS BARBATE CAPABLY HANDBAG CARAMBA BAZAARS PATACAS AREAWAY HALALAS PANAMAS GABBART MACUMBA GAMBADO CABANAS ACACIAS CARAWAY ALFALFA HAWALAS MARANTA SABBATH TAMBACS SANDBAG CARABAO MALACCA CASSATA HAFTARA MAHATMA ATAMANS BALBOAS SAMBUCA DAGOBAS CASABAS CARACAL CASAVAS RATAFIA TAMASHA TAMARAO SABBATS CARBARN HATBAND CASSABA CASCARA CASSAVA FARAWAY LATAKIA PATAMAR BABASSU CARBORA BAHADUR CATAWBA ARCADIA ALAMEDA GALANGA MALARIA ZAMARRA BABYSAT ACROBAT BASIDIA ABFARAD ACAUDAL FARADAY APHAGIA APLASIA ASRAMAS BACCATE CATBOAT BIDARKA LAMBADA MACADAM AGGADAH ATAGHAN TALARIA SAMARAS DICAMBA SCARABS BARMAID BANDANA ARCHAEA HAGGADA AGRAPHA AMANITA SAMSARA CARABID AUCUBAS INDABAS FALBALA PANACEA AGGADAS ANALGIA PAISANA TARAMAS BALANCE ADDABLE TABANID GALABIA HALACHA ADAGIAL ANGARIA APRAXIA TAMARAU CAPABLE ABRADED BALLADS QABALAH CHALAZA HAMMADA GAZANIA PIASAVA SAVANNA ACTABLE BANDAID LAMBDAS ABAXIAL ACANTHA HAMADAS PATAGIA AQUARIA ZANANAS MACABER BADLAND BRADAWL PIASABA ACAPNIA ADAXIAL ASSAGAI ASTASIA PAPAYAN MACABRE SANDDAB ARMBAND ABASIAS ACRASIA DAMIANA MAJAGUA ATAXIAS TANTARA AMBSACE -

Southern California Fleet Report – Bits and Pieces by Rick Olson, SC Fleet Vice Commodore

June, 2014 Southern California Fleet Report – Bits and Pieces by Rick Olson, SC Fleet Vice Commodore Many thanks to the Northern California Fleet for a fun the tanks, plumbing, pump-outs, and systems had to be CYA Board weekend and a bay cruise on Dave & Lynn redone and are now completely new. Olson's unbelievably beautiful, 136-foot Acania. Here in the Southern California fleet, we have had a mild winter Ono has 110-volts from a great inverter system, 110-volt even by our standards ... good boating all year. shore power, 32-volts throughout, but a very limited 12- volt system to run such things as radio and GPS. I couldn't Our SC Fleet Opening find 32-volt macerator motors for the heads, although I Day brunch at the gave up trying pretty easily. I decided to go with readily Parker's Lighthouse available 12-volt pumps. But I was afraid that if I Queensview Room was messed with the 12-volt system already onboard, then followed by an every time someone flushed the toilet, the GPS would afternoon on the boats show that I was in Boise or Cleveland or Kuala Lumpur and a private tour of a or someplace. tall-ship, the 130-foot schooner Tole Mour. "Tole mour" means "a gift of life and health". The schooner was named by the children of the Marshall Islands when the vessel was working there as a hospital ship. Currently she is a full time school ship, training school age children on the art of sailing a So, for power I used 12-volt portable car jumper batteries tall-ship, oceanography, and teamwork. -

Indoor Thermal Comfort Analysis of Infill Buildings in Stone Town Zanzibar

SCHOOL OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE AND BUILDING SCIENCE INDOOR THERMAL COMFORT ANALYSIS OF INFILL BUILDINGS IN STONE TOWN ZANZIBAR LEPERES IRENE NAILANTEI B02/0913/2013 DEDICATION To my late dad. This is for you. iii DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and to the best of my knowledge has not been presented for the award of a degree in this university of Nairobi or any other institution.This thesi is submitted in part fulfillment of the examination requirements for the award of the Bachelors of Architecture degree, Department of Architecture and building science, University of Nairobi. Author: LEPERES IRENE NAILANTEI Signature.....................................................................................Date...................................................... Tutor: Dr Linda Nkatha Signature......................................................................................Date..................................................... Year master:Arch Nobert Musyoki Signature......................................................................................Date.................................................... Chairman, Department of Architecture and building Science,University of Nairobi. Arch. Musau Kimeu Signature.....................................................................................Date...................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT To my Almighty God with whom all things are possible. To my family,Mom,Salaton,Sianoi,Olonana and Soila for your love,prayers -

Catalogue of Model Boats from the Indian Ocean in Thirteen Museum Collections

Catalogue of model boats from the Indian Ocean in thirteen museum collections Each model has been ordered alphabetically by museum name and then alphabetically and numerically sorted by accession number. Museum Accession Number Description Earliest Associated Date Country of Origin Collector Overall Length (mm) if known Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives 1995/001/097 Model Boat - Arab Dow (dhow). Unknown Arab Unknown Bristol Museums, Galleries & Description from CI database: 'This is a small wooden model of an arabian Archives 1997/013/049 dhow. Unknown Arab Unknown Bristol Museums, Galleries & Description from CI database: 'This is a small wooden model of an arabian Archives 1997/013/050 dhow. Unknown Arab Unknown Bristol Museums, Galleries & Model of a Kerala 'Snake Boat'(Chundan Wallam) The boats of Kerala are Archives 1998/133/101 known after their shapes, sizes or purposes. Unknown India Unknown Bristol Museums, Galleries & Model of boat, wood, elongated prows with protrusions, base painted black, Archives T/BANG/102 stand Unknown Bangladesh Unknown Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives T/BANG/103 Model of fishing boat, wood, bamboo awning, oars, base painted black Unknown Bangladesh Unknown Bristol Museums, Galleries & Model of log boat, plaster, 2 male figures with poles, 1 female figure with Archives T/BANG/121 baby, bundles of fish Unknown Bangladesh Unknown Bristol Museums, Galleries & Model of cargo and passenger boat, wood, flat bamboo roof, elongated Archives T/BANG/43 prow, paddle, mast Unknown Bangladesh Unknown Bristol -

CSW12 Complete Variants

CSW12 Complete Variants David Sutton Introduction This document seeks to provide a comprehensive tabulation of variant spelling forms in CSW12, for words up to nine letters in length. It can be viewed as a big brother to 'CSW12 New Variants', which dealt only with new variants introduced in CSW12: that is to say, new words which were simply variant forms of words already existing in CSW7. Again, the idea is to ease at least marginally the task of word learning by grouping the words into 'variant spelling' sets. The following provisos should be noticed. only root forms are listed. It can normally be taken for granted that inflections follow suit. I have not sought to include inflectional variants such as LABELED/LABELLED. only root forms with nine or fewer letters are included, though if these have variant spellings with more than nine letters, those are shown. the large number of –ISE/-IZE variants are omitted. Since CSW7 it can overhelmingly be assumed that any verb ending in –ISE has a corresponding –IZE form; there are exceptions like ADVISE, CHASTISE, DESPISE and FRANCHISE but few that are likely to seduce one into error. it must be remembered that some variants may possess part of speech properties not possessed by other variants of that form. For example, in the case of ALARM/ALARUM/LARUM ALARM and ALARUM are both noun and verb, but LARUM is noun only. Similarly, in the case of ALATE/ALATED, ALATE is both adjective and noun and so can take an –S, but ALATED is adjective only. I have assumed that Scrabble players serious enough to be interested in this document are likely to be aware of such nuances, or prepared to research the matter further on their own account.