Ceratopsids Wall in Past Worlds Gallery Question

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Neoceratopsian Dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Mongolia And

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01222-7 OPEN A neoceratopsian dinosaur from the early Cretaceous of Mongolia and the early evolution of ceratopsia ✉ Congyu Yu 1 , Albert Prieto-Marquez2, Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig 3,4, Zorigt Badamkhatan4,5 & Mark Norell1 1234567890():,; Ceratopsia is a diverse dinosaur clade from the Middle Jurassic to Late Cretaceous with early diversification in East Asia. However, the phylogeny of basal ceratopsians remains unclear. Here we report a new basal neoceratopsian dinosaur Beg tse based on a partial skull from Baruunbayan, Ömnögovi aimag, Mongolia. Beg is diagnosed by a unique combination of primitive and derived characters including a primitively deep premaxilla with four pre- maxillary teeth, a trapezoidal antorbital fossa with a poorly delineated anterior margin, very short dentary with an expanded and shallow groove on lateral surface, the derived presence of a robust jugal having a foramen on its anteromedial surface, and five equally spaced tubercles on the lateral ridge of the surangular. This is to our knowledge the earliest known occurrence of basal neoceratopsian in Mongolia, where this group was previously only known from Late Cretaceous strata. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that it is sister to all other neoceratopsian dinosaurs. 1 Division of Vertebrate Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, New York 10024, USA. 2 Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont, ICTA-ICP, Edifici Z, c/de les Columnes s/n Campus de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès Sabadell, Barcelona, Spain. 3 Department of Biological Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA. 4 Institute of Paleontology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, ✉ Ulaanbaatar 15160, Mongolia. -

A New Troodontid Theropod, Talos Sampsoni Gen. Et Sp. Nov., from the Upper Cretaceous Western Interior Basin of North America

A New Troodontid Theropod, Talos sampsoni gen. et sp. nov., from the Upper Cretaceous Western Interior Basin of North America Lindsay E. Zanno1,2*, David J. Varricchio3, Patrick M. O’Connor4,5, Alan L. Titus6, Michael J. Knell3 1 Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, United States of America, 2 Biological Sciences Department, University of Wisconsin-Parkside, Kenosha, Wisconsin, United States of America, 3 Department of Earth Sciences, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana, United States of America, 4 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, Ohio, United States of America, 5 Ohio Center for Ecology and Evolutionary Studies, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, United States of America, 6 Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Bureau of Land Management, Kanab, Utah, United States of America Abstract Background: Troodontids are a predominantly small-bodied group of feathered theropod dinosaurs notable for their close evolutionary relationship with Avialae. Despite a diverse Asian representation with remarkable growth in recent years, the North American record of the clade remains poor, with only one controversial species—Troodon formosus—presently known from substantial skeletal remains. Methodology/Principal Findings: Here we report a gracile new troodontid theropod—Talos sampsoni gen. et sp. nov.— from the Upper Cretaceous Kaiparowits Formation, Utah, USA, representing one of the most complete troodontid skeletons described from North America to date. Histological assessment of the holotype specimen indicates that the adult body size of Talos was notably smaller than that of the contemporary genus Troodon. Phylogenetic analysis recovers Talos as a member of a derived, latest Cretaceous subclade, minimally containing Troodon, Saurornithoides, and Zanabazar. -

MEET the DINOSAURS! WHAT’S in a NAME? a LOT If You Are a Dinosaur!

MEET THE DINOSAURS! WHAT’S IN A NAME? A LOT if you are a dinosaur! I will call you Dyoplosaurus! Most dinosaurs get their names from the ancient Greek and Latin languages. And I will call you Mojoceratops! And sometimes they are named after a defining feature on their body. Their names are made up of word parts that describe the dinosaur. The name must be sent to a special group of people called the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature to be approved! Did You The word DINOSAUR comes from the Greek word meaning terrible lizard and was first said by Know? Sir Richard Owen in 1841. © 2013 Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo & Aquarium® | 3 SEE IF YOU CAN FIND OUT THE MEANING OF SOME OF OUR DINOSAUR’S NAMES. Dinosaur names are not just tough to pronounce, they often have meaning. Dinosaur Name MEANING of Dinosaur Name Carnotaurus (KAR-no-TORE-us) Means “flesh-eating bull” Spinosaurus (SPY-nuh-SORE-us) Dyoplosaurus (die-o-pluh-SOR-us) Amargasaurus (ah-MAR-guh-SORE-us) Omeisaurus (Oh-MY-ee-SORE-us) Pachycephalosaurus (pak-ee-SEF-uh-low-SORE-us) Tuojiangosaurus (toh-HWANG-uh-SORE-us) Yangchuanosaurus (Yang-chew-ON-uh-SORE-us) Quetzalcoatlus (KWET-zal-coe-AT-lus) Ouranosaurus (ooh-RAN-uh-SORE-us) Parasaurolophus (PAIR-uh-so-ROL-uh-PHUS) Kosmoceratops (KOZ-mo-SARA-tops) Mojoceratops (moe-joe-SEH-rah-tops) Triceratops (try-SER-uh-TOPS) Tyrannosaurus rex (tuh-RAN-uh-SORE-us) Find the answers by visiting the Resource Library at Carnotaurus A: www.OmahaZoo.com/Education. Search word: Dinosaurs 4 | © 2013 Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo & Aquarium® DINO DEFENSE All animals in the wild have to protect themselves. -

Leophils Welt Hauptthema Fußball

Leophils Welt Die Zeitschrift für die Mitglie- der der Jungen Briefmarken- freunde Hessen Ausgabe 2 Jahrgang 4 Hauptthema Fußball www.briefmarkenjugend-hessen.de Inhalt Vorwort ............................................................................................................................. 3 Fußball Europameisterschaft der Männer 2016 in Frankreich ............................. 5 Die Geschichte des Fußballs ......................................................................................... 8 Fußball bei den Olympischen Spielen ........................................................................ 12 Entenschnabel-Dinosaurier, Teil 4 ............................................................................ 14 Neue Sondermarken in Deutschland ......................................................................... 21 Der Basilisk von Wien .................................................................................................. 30 Aus den Gruppen ........................................................................................................... 32 Muss eine Briefmarke immer auf Papier gedruckt sein? .................................... 34 Erzabtei St. Peter in Salzburg ................................................................................. 36 Dauerserien - der Reiz der Komplettierung ........................................................... 37 Rätsel .............................................................................................................................. 39 Hier stimmt -

38-Simpson Et Al (Wahweap Fm).P65

Sullivan et al., eds., 2011, Fossil Record 3. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin 53. 380 UPPER CRETACEOUS DINOSAUR TRACKS FROM THE UPPER AND CAPPING SANDSTONE MEMBERS OF THE WAHWEAP FORMATION, GRAND STAIRCASE-ESCALANTE NATIONAL MONUMENT, UTAH, U.S.A. EDWARD L. SIMPSON1, H. FITZGERALD MALENDA1, MATTATHIAS NEEDLE1, HANNAH L. HILBERT-WOLF2, ALEX STEULLET3, KEN BOLING3, MICHAEL C. WIZEVICH3 AND SARAH E. TINDALL1 1 Department of Physical Sciences, Kutztown University, Kutztown, PA 19530; 2 Department of Geology, Carleton College, Northfield, MN, 55057; 3 Central Connecticut State University, Department of Physics and Earth Sciences, New Britain, Connecticut 06050, USA Abstract—Tridactyl tracks were identified in the fluvial strata of the Upper Cretaceous Wahweap Formation in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, southern Utah, U.S.A. An isolated track and a trackway are located within the upper member at the Cockscomb, and an isolated track is in the capping sandstone member at Wesses Canyon. The upper member tracks are tridactyl pes imprints consisting of a longer, blunt digit III and shorter, blunt digits II-IV. This trace corresponds well to an ornithropod dinosaur as the trackmaker. The capping sandstone member track is a tridactyl pes with an elongate digit III and shorter digits II-IV. Claw impressions are present on the terminus of digits II and III. This trace is consistent with the pes impression of a one meter tall theropod. The tracks further highlight the diversity of dinosaurs in the capping sandstone of the Wahweap Formation. INTRODUCTION During the Late Cretaceous, North America, in particular the west- ern United States, was the site of a radiation of new dinosaurian genera. -

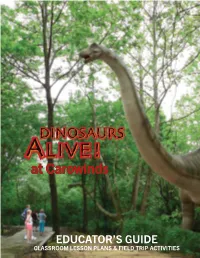

At Carowinds

at Carowinds EDUCATOR’S GUIDE CLASSROOM LESSON PLANS & FIELD TRIP ACTIVITIES Table of Contents at Carowinds Introduction The Field Trip ................................... 2 The Educator’s Guide ....................... 3 Field Trip Activity .................................. 4 Lesson Plans Lesson 1: Form and Function ........... 6 Lesson 2: Dinosaur Detectives ....... 10 Lesson 3: Mesozoic Math .............. 14 Lesson 4: Fossil Stories.................. 22 Games & Puzzles Crossword Puzzles ......................... 29 Logic Puzzles ................................. 32 Word Searches ............................... 37 Answer Keys ...................................... 39 Additional Resources © 2012 Dinosaurs Unearthed Recommended Reading ................. 44 All rights reserved. Except for educational fair use, no portion of this guide may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any Dinosaur Data ................................ 45 means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other without Discovering Dinosaurs .................... 52 explicit prior permission from Dinosaurs Unearthed. Multiple copies may only be made by or for the teacher for class use. Glossary .............................................. 54 Content co-created by TurnKey Education, Inc. and Dinosaurs Unearthed, 2012 Standards www.turnkeyeducation.net www.dinosaursunearthed.com Curriculum Standards .................... 59 Introduction The Field Trip From the time of the first exhibition unveiled in 1854 at the Crystal -

John Bell Hatcher.1 Bokn October 11, 1861

568 Obituary—J. B. Hatcher. " Description of a New Genus [Stelidioseris] of Madreporaria from the Sutton Stone of South "Wales": Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc, vol. xlix (1893), pp. 574-578, and pi. xx. " Observations on some British Cretaceous Madreporaria, with the Description of two New Species " : GEOL. MAG., 1899, pp. 298-307. " Description of a Species of Heteraslraa lrom the Lower Rhsetic of Gloucester- shire" : Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc, lix (1903), pp. 403-407, and figs, in text. JOHN BELL HATCHER.1 BOKN OCTOBER 11, 1861. DIED JULY 3, 1904. THE Editor of the Annals of the Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S., records with deep regret the death, on July 3rd, 1904, of his trusted associate, Mr. John Bell Hatcher. Mr. Hatcher was born at Cooperstown, Brown County, Illinois, on October 11th, 1861. He was the son of John and Margaret C. Hatcher. The family is Virginian in extraction. In his boyhood his parents removed to Greene County, Iowa, where his father, who with his mother survive him, engaged in agricultural pursuits near the town of Cooper. He received his early education from his father, who in the winter months combined the work of teaching in the schools with labour upon his farm. He also attended the public schools of the neighbourhood. In 1880 he entered Grinnell College, Iowa, where he remained for a short time, and then went to Yale College, where he took the degree of Bachelor in Philosophy, in July, 1884. While a student at Yale his natural fondness for scientific pursuits asserted itself strongly, and he attracted the attention of the late Professor Othniel C. -

Brains and Intelligence

BRAINS AND INTELLIGENCE The EQ or Encephalization Quotient is a simple way of measuring an animal's intelligence. EQ is the ratio of the brain weight of the animal to the brain weight of a "typical" animal of the same body weight. Assuming that smarter animals have larger brains to body ratios than less intelligent ones, this helps determine the relative intelligence of extinct animals. In general, warm-blooded animals (like mammals) have a higher EQ than cold-blooded ones (like reptiles and fish). Birds and mammals have brains that are about 10 times bigger than those of bony fish, amphibians, and reptiles of the same body size. The Least Intelligent Dinosaurs: The primitive dinosaurs belonging to the group sauropodomorpha (which included Massospondylus, Riojasaurus, and others) were among the least intelligent of the dinosaurs, with an EQ of about 0.05 (Hopson, 1980). Smartest Dinosaurs: The Troodontids (like Troödon) were probably the smartest dinosaurs, followed by the dromaeosaurid dinosaurs (the "raptors," which included Dromeosaurus, Velociraptor, Deinonychus, and others) had the highest EQ among the dinosaurs, about 5.8 (Hopson, 1980). The Encephalization Quotient was developed by the psychologist Harry J. Jerison in the 1970's. J. A. Hopson (a paleontologist from the University of Chicago) did further development of the EQ concept using brain casts of many dinosaurs. Hopson found that theropods (especially Troodontids) had higher EQ's than plant-eating dinosaurs. The lowest EQ's belonged to sauropods, ankylosaurs, and stegosaurids. A SECOND BRAIN? It used to be thought that the large sauropods (like Brachiosaurus and Apatosaurus) and the ornithischian Stegosaurus had a second brain. -

Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-25 Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores Borkovic, Benjamin Borkovic, B. (2013). Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26635 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/498 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores by Benjamin Borkovic A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2013 © Benjamin Borkovic 2013 Abstract Evidence for sexual dimorphism was investigated in the horncores of two ceratopsid dinosaurs, Triceratops and Centrosaurus apertus. A review of studies of sexual dimorphism in the vertebrate fossil record revealed methods that were selected for use in ceratopsids. Mountain goats, bison, and pronghorn were selected as exemplar taxa for a proof of principle study that tested the selected methods, and informed and guided the investigation of sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs. Skulls of these exemplar taxa were measured in museum collections, and methods of analysing morphological variation were tested for their ability to demonstrate sexual dimorphism in their horns and horncores. -

The Dinosaur Park - Bearpaw Formation Transition in the Cypress Hills Region of Southwestern Saskatchewan, Canada Meagan M

The Dinosaur Park - Bearpaw Formation Transition in the Cypress Hills Region of Southwestern Saskatchewan, Canada Meagan M. Gilbert Department of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan; [email protected] Summary The Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation (DPF) is a south- and eastward-thinning fluvial to marginal marine clastic-wedge in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin. The DPF is overlain by the Bearpaw Formation (BF), a fully marine clastic succession representing the final major transgression of the epicontinental Western Interior Seaway (WIS) across western North America. In southwestern Saskatchewan, the DPF is comprised of marginal marine coal, carbonaceous shale, and heterolithic siltstone and sandstone grading vertically into marine sandstone and shale of the Bearpaw Formation. Due to Saskatchewan’s proximity to the paleocoastline, 5th order transgressive cycles resulted in the deposition of multiple coal seams (Lethbridge Coal Zone; LCZ) in the upper two-thirds of the DPF in the study area. The estimated total volume of coal is 48109 m3, with a gas potential of 46109 m3 (Frank, 2005). The focus of this study is to characterize the facies and facies associations of the DPF, the newly erected Manâtakâw Member, and the lower BF in the Cypress Hills region of southwestern Saskatchewan utilizing core, outcrop, and geophysical well log data. This study provides a comprehensive sequence stratigraphic overview of the DPF-BF transition in Saskatchewan and the potential for coalbed methane exploration. Introduction The Dinosaur Park and Bearpaw Formations in Alberta, and its equivalents in Montana, have been the focus of several sedimentologic and stratigraphic studies due to exceptional outcrop exposure and extensive subsurface data (e.g., McLean, 1971; Wood, 1985, 1989; Eberth and Hamblin, 1993; Tsujita, 1995; Catuneanu et al., 1997; Hamblin, 1997; Rogers et al., 2016). -

Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in Later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2020-0174.R1 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 04-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Holtz, Thomas; University of Maryland at College Park, Department of Geology; NationalDraft Museum of Natural History, Department of Geology Keyword: Dinosaur, Ontogeny, Theropod, Paleocology, Mesozoic, Tyrannosauridae Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special Tribute to Dale Russell Issue? : © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 91 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: 2 Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous 3 Asiamerica 4 5 6 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 7 8 Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA 9 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20013 USA 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 ORCID: 0000-0002-2906-4900 Draft 12 13 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 14 Department of Geology 15 8000 Regents Drive 16 University of Maryland 17 College Park, MD 20742 18 USA 19 Phone: 1-301-405-4084 20 Fax: 1-301-314-9661 21 Email address: [email protected] 22 23 1 © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 91 24 ABSTRACT 25 Well-sampled dinosaur communities from the Jurassic through the early Late Cretaceous show 26 greater taxonomic diversity among larger (>50kg) theropod taxa than communities of the 27 Campano-Maastrichtian, particularly to those of eastern/central Asia and Laramidia. -

Histology and Ontogeny of Pachyrhinosaurus Nasal Bosses By

Histology and Ontogeny of Pachyrhinosaurus Nasal Bosses by Elizabeth Kruk A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Systematics and Evolution Department of Biological Sciences University of Alberta © Elizabeth Kruk, 2015 Abstract Pachyrhinosaurus is a peculiar ceratopsian known only from Upper Cretaceous strata of Alberta and the North Slope of Alaska. The genus consists of three described species Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis, Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai, and Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum that are distinguishable by cranial characteristics, including parietal horn shape and orientation, absence/presence of a rostral comb, median parietal bar horns, and profile of the nasal boss. A fourth species of Pachyrhinosaurus is described herein and placed into its phylogenetic context within Centrosaurinae. This new species forms a polytomy at the crown with Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis and Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum, with Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai falling basal to that polytomy. The diagnostic features of this new species are an apomorphic, laterally curved Process 3 horns and a thick longitudinal ridge separating the supraorbital bosses. Another focus is investigating the ontogeny of Pachyrhinosaurus nasal bosses in a histological context. Previously, little work has been done on cranial histology in ceratopsians, focusing instead on potential integumentary structures, the parietals of Triceratops, and how surface texture relates to underlying histological structures. An ontogenetic series is established for the nasal bosses of Pachyrhinosaurus at both relative (subadult versus adult) and fine scale (Stages 1-5). It was demonstrated that histology alone can indicate relative ontogenetic level, but not stages of a finer scale. Through Pachyrhinosaurus ontogeny the nasal boss undergoes increased vascularity and secondary remodeling with a reduction in osteocyte lacunar density.