Sample Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Its HCM Tire Line for Municipal Use Mitas Is Continuing to Expand Its Range of HCM (High Capacity Municipal) Tires

Vol. 16 | No. 1 | 2018 A QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER FOR CUSTOMERS AND FRIENDS OF MITAS Mitas expands its HCM tire line for municipal use Mitas is continuing to expand its range of HCM (High Capacity Municipal) tires. These are univer- sal tires designed for a wide range of machinery, primarily in municipal services. For 2018 the company is planning to launch four new variants, some of which will be with a new, sixty-fi ve per- cent profi le. he sizes will be 540/65R30 IND 161A8/156D, T650/65R42 IND 176A8/171D, 360/80R24 IND 144A8/139D and 440/80R34 IND 159A8/155D. The new 65% profi le series tires are designed mainly for high-horsepower trac- tors and can carry a load of 4625 kg at 40 km/h or 4000 kg at 65 km/h (front), and 7100 kg at 40 km/h or 6150 kg at 65 km/h (rear). The tire construction, featuring steel breakers, ensures high puncture resistance and on-road stability, while the unique cascade tread lugs de- sign of the HCM tires provides optimal self-clea- ning properties and improves off-road capability in the mud and snow. The tread pattern ensures that the HCM tires provide excellent traction in all weathers while keeping noise levels low. Mitas thoroughly tested the drivability of the HCM tires under extreme winter conditions at the Ivalo testing circuit in Finland. Inside the Arctic Circle, HCM tires were tested under harsh winter conditions inside the Arctic Circle in Finland. Continued on page 2 Be IN IN THE WORLD OF MITAS! ear readers, you are reading the very first issue of the Mitas IN facturer, understands this and so informs you of news and innovative techno- Dnewsletter. -

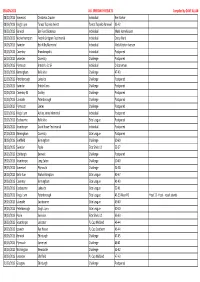

Fixture List

SEASON 2013 U.K. SPEEDWAY RESULTS Compiled by DAVE ALLAN 08/02/2013 Somerset Christmas Cracker Individual Ben Barker 08/03/2013 King's Lynn Tomas Topinka Select Tomas Topinka Farewell 36-42 09/03/2013 Berwick Ben Fund Bonanza Individual Mads Korneliussen 10/03/2013 Wolverhampton Fredrik Lindgren Testimonial Individual Darcy Ward 14/03/2013 Swindon Bob Kilby Memorial Individual Niels-Kristian Iversen 15/03/2013 Coventry Brandonapolis Individual Postponed 16/03/2013 Leicester Coventry Challenge Postponed 16/03/2013 Plymouth British U-21 SF Individual D.Stoneman 20/03/2013 Birmingham Belle Vue Challenge 47-43 21/03/2013 Peterborough Lakeside Challenge Postponed 21/03/2013 Swindon British Lions Challenge Postponed 22/03/2013 Coventry NL Dudley Challenge Postponed 22/03/2013 Lakeside Peterborough Challenge Postponed 22/03/2013 Plymouth Exeter Challenge Postponed 22/03/2013 King's Lynn Ashley Jones Memorial Individual Postponed 23/03/2013 Eastbourne Belle Vue Elite League Postponed 24/03/2013 Scunthorpe David Howe Testimonial Individual Postponed 27/03/2013 Birmingham Coventry Elite League Postponed 28/03/2013 Sheffield Birmingham Challenge 30-60 28/03/2013 Swindon Poole Elite Shield L1 53-37 29/03/2013 Edinburgh Berwick Challenge Postponed 29/03/2013 Scunthorpe Long Eaton Challenge 50-40 29/03/2013 Somerset Plymouth Challenge 54-38 29/03/2013 Belle Vue Wolverhampton Elite League 43-47 29/03/2013 Coventry Birmingham Elite League 41-49 29/03/2013 Eastbourne Lakeside Elite League 52-41 29/03/2013 King's Lynn Peterborough Elite League 41-33 Aban -

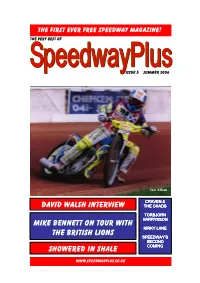

Showered in Shale Mike Bennett On

THE FIRST EVER FREE SPEEDWAY MAGAZINE! THE VERY BEST OF ISSUE 5 – SUMMER 2006 Ian Adam CRAVEN & DAVID WALSH INTERVIEW THE CHADS TORBJORN TORBJORN HARRYSHARRYSSSSSONONONON MIKE BENNETT ON TOUR WITH KIRKY LANE THE BRITISH LIONS SPEEDWAY’S SECOND COMING SHOWERED IN SHALE WWW.SPEEDWAYPLUS.CO.UK =EDITORIAL We're now up to issue five of the CONTENTS magazine and we thank those of you who've downloaded them all so far INTERVIEW: DAVID WALSH 3 and offer a warm welcome to anyone joining us for the first time. Back issues are still available to download COLUMNIST: DAVE GREEN 10 from the website if you'd like to see our previous editions. COLUMNIST: DAVE GIFFORD 11 We catch up with David Walsh for our big BOOK EXTRACT: SHOWERED IN SHALE 13 interview this edition. 'Walshie' was always a big fans’ favourite and contributed to league title wins for four different teams. TRACK PICTURES: PARKEN 17 He talks us through his long career and lets us know what he's up to these days. COLUMNIST: MIKE BENNETT 18 Mike Bennett looks back on the Great l Britian tour of Australia in 1988. Which of TRACK PICTURES: KIRKMANSHULME LANE 20 the riders ended up in a swimming pool wearing full riding kit? Why were the riders LIVERPOOL: CRAVEN & THE CHADS 21 chased out of a shopping mall? The answers are in MB's column. COLUMNIST: CHRIS SEAWARD 23 We also feature an exclusive extract from Jeff Scott's brilliant travelogue - "Showered in Shale". This book has been described as a “printed documentary” and that's an excellent summary of the contents. -

Mitas Moto Newsletter

MITAS MOTO NEWSLETTER #4 / 2020 Motorsport news Bartosz Zmarzlik is 2020 FIM Speedway World Champion Mitas rider Bartosz Zmarzlik #95 became 2020 FIM Speedway Grand Prix World Champion! With this title he became Polands first-ever double world champion after retaining his FIM Speedway Grand Prix World Championship in Torun, Poland. Zmarzlik becomes only the third rider in SGP history to win back-to-back championships, so a massive congratulations is in order! However we have to mention the 2nd and 3rd runner ups - the Great Britain icon Tai Woffinden and Swedish star Fredrik Lindgren. Interview with Valerio Lata, the 85cc FIM Junior Motocross World Champion in 2019 Valerio began racing in 2010, when he was barely five years old. Already in 2011 he won the Italian mini ‘50 championship. Ever since then he has kept his career moving forward and won his first world title in 2019 to become the 85cc FIM Junior Motocross World Champion. Mitas is glad that he has won this prestigious title on Mitas tyres. We have been talking to him one year after this great achievement. Photo credit: Claudio Cei mitas-moto.com 1 Can you tell us a bit about your early days of riding and how you got into racing? When I was four, I went to Latina with my parents to watch a motocross race because my father practiced it and it is still his favourite sport. On that occasion I tried a small motocross bike in the parking lot and I liked it so much that I started training and at the age of five I took part in my first race. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Beswick Animals

BESWICK ANIMALS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Diana Callow,John Callow,Marilyn Sweet,Peter Sweet | 400 pages | 01 Apr 2011 | CHARLTON PRESS | 9780889683464 | English | Toronto, Canada Beswick Animals PDF Book Sponsored Listings. Lesser known breeds, such as Galloways, had shorter runs and consequently rank high on the most-wanted list. Realism and accuracy were key to their appeal: as the desirable characteristics of Hereford cattle changed over time so did Gredington's models of the breed. Beswick Dog Filter Applied. Filter 1. Item Location see all. European Union. Delivery options see all. Best Offer. In , Lucy Beswick suggested bringing to life the illustrations in the Beatrix Potter books. Stoke Potters Stoke Spitfires. It is a reflection of collecting taste that the firm's range of s wares, such as the Zebra pattern, will today command more attention than older pieces. The Snowman and the Snowdog figures are just some of the nursery figures still being produced. Beatrix Potter Beswick Figurines. UK Only. Caldon Canal Trent and Mersey Canal. Continued expansion enabled the acquisition of the adjoining factory in to accommodate offices, warehousing and new potting and firing facilities. Not Specified. Sold items. Got one to sell? Vintage Fashion Textiles. By the end of , Royal Doulton ceased production of all Beswick products and in the Gold Street works were sold off to property developers. Certainly some collectors of Beatrix Potter figures only look for those with the pre 'gold' mark replaced by the 'brown' mark a couple of years after Beswick were taken over by Royal Doulton in , believing them to be superior. -

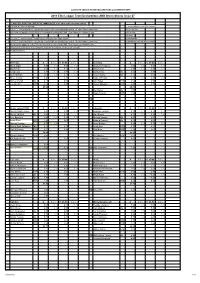

2016 Elite League Team Declarations and Green Sheets Issue 27

2016 ELITE LEAGUE TEAM DECLARATIONS and GREEN SHEETS 2016 Elite League Team Declarations AND Green Sheets Issue 27 TEAM DECLARATION EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY (or date stated by team name) A Column A - current average * = assessed MA due to one of the following B S.R.17.7.1 Absent Rider's actual achieved CMA is calculated as actual +5%(for Home team only), New Foreign Rider but does not apply to a d/u Rider or one with an assessed CMA. This relates to column A only. Converted MA New Rider C Column C - new average, if applicable, effective from date stated Re-assessed MA D S.R.17.7.1 Absent Rider's actual achieved CMA is calculated as actual +5%(for Home team only), Established MA older than previous season but does not apply to a d/u Rider or one with an assessed CMA. This relates to column C only. ** Hiererarchical Order is in accordance with the declaration of the team/s below. OG Outgoing rider/s Belle Vue A B 5% C 05-09 D 5% Coventry A B 5% C 05-09 D 5% 1 Matej Zagar 7.45 7.82 7.55 7.93 1 Krzysztof Kasprzak 8.04 8.44 7.91 8.31 2 Max Fricke 6.84 7.18 7.14 7.50 2 Chris Harris 6.78 7.12 6.77 7.11 3 Craig Cook 6.83 7.17 6.73 7.07 3 Danny King d/u 6.49 6.87 4 Scott Nicholls 6.64 6.97 6.28 6.59 4 Jason Garrity d/u 5.75 6.05 5 Steve Worrall EDR 6.46 6.37 5 Kacper Woryna 4.79 5.03 4.80 5.04 6 Richie Worrall d/u 6.18 6.00 6 Josh Bates EDR 4.56 4.90 7 Joe Jacobs EDR 3.12 3.95 7 James Sarjeant EDR 3.66 3.91 43.52 40.07 4 Ben Barker d/u* 4.54 7 Adam Roynon EDR 4.00 OG OG King's Lynn eff 30/8 A B 5% C 05-09 D 5% Lakeside A B 5% C 05-09 D 5% 1 Niels -

World Finals 1936-1994

No Rider Name 1 2 3 4 5 Tot BP TOT No Rider Name 1 2 3 4 5 Tot BP TOT No Rider Name 1 2 3 4 5 Tot BP TOT 1 Dicky Case 1 0 3 1 2 7 9 16 7 Ginger Lees 2 0 1 0 1 4 7 11 13 Bob Harrison 0 0 2 0 3 5 10 15 2 Frank Charles 3 3 0 2 0 8 12 20 8 Bluey Wilkinson 3 3 3 3 3 15 10 25 14 Eric Langton 3 3 3 2 2 13 13 26 3 Wal Phillips 1 1 0 2 1 5 7 12 9 Cordy Milne 2 2 1 3 3 11 9 20 15 Vic Huxley 1 2 0 2 2 7 10 17 4 George Newton 0 0 3 1 0 4 12 16 10 Bill Pritcher 0 1 0 0 1 2 6 8 16 Morian Hansen 2 1 2 0 0 5 10 15 5 Jack Ormston 1 1 2 3 1 8 9 17 11 Lionel Van Praag 3 3 3 2 3 14 12 26 R17 Norman Parker 1 1 6 7 6 Arthur Atkinson 0 2 1 0 0 3 6 9 12 Jack Milne 1 2 1 0 2 6 9 15 R18 Blazer Hansen 0 5 5 HEAT No. RIDER NAME COL COMMENTS No. RIDER NAME COL COMMENTS No. RIDER NAME COL COMMENTS PTS 1 Dicky Case R 2 2 Frank Charles R 0 2 Frank Charles R 0 2 Frank Charles B 3 6 Arthur Atkinson B 1 8 Bluey Wilkinson B 3 1 9 17 3 Wal Phillips W 1 11 Lionel Van Praag W 3 10 Bill Pritcher W 1 73.60 4 George Newton Y Fell 0 76.60 16 Morian Hansen Y 2 78.60 15 Vic Huxley Y 2 5 Jack Ormston R 1 1 Dicky Case R 3 1 Dicky Case R 2 6 Arthur Atkinson B 0 5 Jack Ormston B 2 7 Ginger Lees B 1 2 10 18 7 Ginger Lees W 2 12 Jack Milne W 1 9 Cordy Milne W 3 77.20 8 Bluey Wilkinson Y 3 78.60 15 Vic Huxley Y 0 78.80 16 Morian Hansen Y 0 9 Cordy Milne R 2 2 Frank Charles R 2 3 Wal Phillips R 1 10 Bill Pritcher B 0 7 Ginger Lees B 1 6 Arthur Atkinson B 0 3 11 19 11 Lionel Van Praag W 3 12 Jack Milne (US) W 0 12 Jack Milne W 2 75.80 12 Jack Milne Y 1 76.80 14 Eric Langton Y 3 79.80 13 -

Cradley Heath 1967 – Information Required

Cradley Heath Speedway 1967 Statistical Record Contents Index Of Meetings Meeting Details Nigel Nicklin & Roger Beaman – Issue 1 – 28th March 2014 Cradley Heath Speedway 1967 - Index Of Meetings Month Date Opponents Competition Venue Result For Agst Page March 24 Wolverhampton Challenge Away Lost 29 49 3 25 Wolverhampton Challenge Home Lost 36 41 4 28 Long Eaton British League Away Lost 28 50 5 April 1 Newport British League Home Lost 35 43 6 6 Sheffield British League Away Lost 27 48 7 8 Poole British League Home Won 40 37 8 13 Oxford British League Away Lost 27 51 9 15 Newcastle British League Home Lost 37 41 10 21 Hackney British League Away Lost 30 48 11 22 Long Eaton Knockout Cup Home Postponed - Rain 12 24 Newcastle British League Away Lost 38 40 13 29 Coventry British League Away Lost 22 56 14 May 1 Halifax British League Home Lost 36 42 15 6 Wolverhampton British League Home Won 41 37 16 8 Exeter British League Away Lost 24 54 17 13 World Champs QR Individual Home Ivor Brown 18 20 Sheffield British League Home Won 42 36 19 23 West Ham British League Away Lost 26 52 20 27 Swindon British League Home Won 46 31 21 June 3 Oxford British League Home Lost 38 39 22 5 Midland Riders QR Individual Home Rick France 23 10 Exeter British League Home Won 47 30 24 16 Newport British League Away Lost 22 55 25 17 Kings Lynn British League Home Won 39 38 26 19 Long Eaton Knockout Cup Home Lost 45 51 27 23 Wolverhampton British League Away Lost 27 51 28 24 Glasgow British League Home Lost 37 41 29 30 Glasgow British League Away Lost 32 46 30 July -

FIM Speedway Grand Prix World Championship™. 2014 Auckland, New Zealand 5Th April 2014 FINAL RESULTS

FIM Speedway Grand Prix World Championship™. 2014 Auckland, New Zealand 5th April 2014 FINAL RESULTS Placing Rider N° Name FMN Nationality Points 1st 84 Martin Smolinski DMSB GER 15 2nd 5 Nicki Pedersen DMU DEN 19 3rd 507 Krzysztof Kasprzak PZM POL 17 4th 66 Fredrik Lindgren SVEMO SWE 13 5th 91 Kenneth Bjerre DMU DEN 11 6th 23 Chris Holder MA AUS 11 7th 33 Jaroslaw Hampel PZM POL 8 8th 100 Andreas Jonsson SVEMO SWE 7 9th 1 Tai Woffinden ACU GBR 7 10th 45 Greg Hancock AMA USA 6 11th 55 Matej Zagar AMZS SLO 6 12th 88 Niels K Iversen DMU DEN 6 13th 43 Darcy Ward MA AUS 5 14th 75 Troy Batchelor MA AUS 4 15th 16 Jason Bunyan MNZ NZ 2 16th 37 Chris Harris ACU GBR 0 17th 17 Andrew Aldridge MNZ NZ 0 18th 18 Grant Tregoning MNZ NZ 0 Signature of Jury President Signature of Clerk of the Course Armando Castagna (FMI) Tony Briggs (MNZ) When it is sent by E-mail, only the name of the Jury President and the Clerk of the Course are required. These results must be sent to the journalists and to the FIM Administration right after the meeting, as per the list of fax numbers and E-mails provided by the Jury President. FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE MOTOCYCLISME 11 Route Suisse – 1295 Mies / Switzerland Compiled Using KanDysoft GP Spreadsheet www.kandysoft.com ©All Rights Reserved BSI Speedway Ltd FIM Speedway Grand Prix World Championship™. 2014 FIM Speedway Grand Prix of New Zealand FIM Jury President :- Armando Castagna (Italy) Auckland, New Zealand. -

GENERAL CATALOGUE 2019 Our History Is Our Future

Ride Regina. Be one of us! P.C13D19EC GENERAL CATALOGUE 2019 Our history is our future. The Wall of Champions. In 2019, Regina will celebrate its Innocenti’s “Lambretta”. The original Bayliss, Biaggi, Lorenzo, Rossi, by combining innovation with an 100th anniversary. The company design of Lambretta did not have a Everts, Cairoli, Herlings, Eriksson, outstanding and consistently high quality 1949 Bruno Ruffo 250cc Class 1974 Phil Read 500cc Class 1987 Jorge Martinez 80cc Class 1995 Petteri Silvan Enduro 125cc 2003 Anders Eriksson Enduro 400cc 2011 Antonio Cairoli MX1 was founded in 1919, initially transmission by chain, but after the Prado, level has allowed Regina 1950 Umberto Masetti 500cc Class 1974 M. Rathmell Trial 1987 Virginio Ferrari TT F1 1995 Anders Eriksson Enduro 350cc 2003 Juha Salminen Enduro 500cc 2011 Ken Roczen MX2 1950 Bruno Ruffo 125cc Class 1975 Paolo Pileri 125cc Class 1987 John Van Den Berk 125cc MX 1995 Jordi Tarrés Trial 2004 James Toseland WSBK 2011 Greg Hancock Speedway manufacturing chains and freewheels problems experienced with the cardan and Remes to be a market leader, 1951 Carlo Ubbiali 125cc Class 1975 Walter Villa 250cc Class 1987 Jordi Tarrés Trial 1995 Kari Tiainen Enduro 500cc 2004 Stefan Everts MX1 2012 Marc Marquez Moto 2 for bicycles. In those days, the transmission, the company asked for appreciated the enabling it to serve 1951 Bruno Ruffo 250cc Class 1975 R. Steinhausen/J. Huber Sidecar 1988 Jorge Martinez 80cc Class 1996 Max Biaggi 250cc Class 2004 Juha Salminen Enduro 2 2012 Max Biaggi WSBK -

The Speedway Researcher

1 - but we shall not know until we make the effort ! How many people The Speedway Researcher are interested ? Who knows until we start ! Promoting Research into the History of Speedway and Dirt Track Racing I thought the launch of “The Speedway Researcher: would be an ideal Volume No.2 No.1 - June 1999 catalyst to get the project underway. To varying degrees I had started SUBSCRIBERS : 100 + working on 1939,1946 and 1947 seasons in “fits and starts”. That is why I have offered to do these seasons. Perhaps other enthusiasts THANKS FOR THE SUPPORT would consider doing other seasons ? What I need is people who can volunteer information to get in touch with me. Although I’ll be very The response to our second volume is very welcome and the response to our interested to have the details, the project is not for my personal benefit questionnaire is very heartening. We welcome the warm words of support and alone but hopefully will form an authoritative source of help for genuine it appears we are keeping most of our subscribers happy. We are particularly researchers in the future. delighted to read of new contacts being established and the helpful exchange Obviously there will be a number of matters to be considered if the of information. We are even more delighted to read of new research work project develops. Such as - How will the information be stored, being undertaken after The Speedway Researcher sparked off the work. presented and disseminated ? What about costs and charges ? Should We probably will never reach the 100 pages per edition asked for by one we aim for formal publications under “The Speedway Researcher” ? reader but we will add another four pages from the next edition onwards. -

T Call Me Clyde!’

‘DON’T CALL ME CLYDE!’ - Jazz Journey of a Sixties Stomper - PETER KERR Don't Call Me Clyde_INSIDES.indd 1 25/05/2016 17:35:51 Published by Oasis-WERP 2016 ISBN: 978-0-9576586-2-2 Copyright © Peter Kerr 2016 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the written permission of the copyright owner. The right of Peter Kerr to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, designs and Patents Act 1988. A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library www.peter-kerr.co.uk Cover design © Glen Kerr Typeset by Ben Ottridge www.benottridge.co.uk Don't Call Me Clyde_INSIDES.indd 2 25/05/2016 17:35:51 ALSO BY THIS AUTHOR Thistle Soup Snowball Oranges Mañana, Mañana Viva Mallorca! A Basketful of Snowflakes From Paella to Porridge The Mallorca Connection The Sporran Connection The Cruise Connection Fiddler on the Make The Gannet Has Landed Song of the Eight Winds ABOUT THE AUTHOR Best-selling Scottish author Peter Kerr is a former jazz musician, record producer and farmer. His award-winning Snowball Oranges series of humorous travel books was inspired by his family’s adventures while running a small orange farm on the Spanish island of Mallorca during the 1980s. Peter’s books are sold worldwide and have been translated into several languages. In the early 1960s he was clarinettist/leader of Scotland’s premier jazz band, the Clyde Valley Stompers.