T Call Me Clyde!’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Showered in Shale Mike Bennett On

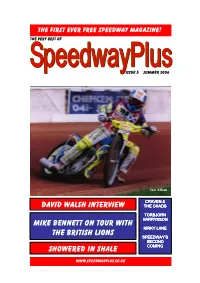

THE FIRST EVER FREE SPEEDWAY MAGAZINE! THE VERY BEST OF ISSUE 5 – SUMMER 2006 Ian Adam CRAVEN & DAVID WALSH INTERVIEW THE CHADS TORBJORN TORBJORN HARRYSHARRYSSSSSONONONON MIKE BENNETT ON TOUR WITH KIRKY LANE THE BRITISH LIONS SPEEDWAY’S SECOND COMING SHOWERED IN SHALE WWW.SPEEDWAYPLUS.CO.UK =EDITORIAL We're now up to issue five of the CONTENTS magazine and we thank those of you who've downloaded them all so far INTERVIEW: DAVID WALSH 3 and offer a warm welcome to anyone joining us for the first time. Back issues are still available to download COLUMNIST: DAVE GREEN 10 from the website if you'd like to see our previous editions. COLUMNIST: DAVE GIFFORD 11 We catch up with David Walsh for our big BOOK EXTRACT: SHOWERED IN SHALE 13 interview this edition. 'Walshie' was always a big fans’ favourite and contributed to league title wins for four different teams. TRACK PICTURES: PARKEN 17 He talks us through his long career and lets us know what he's up to these days. COLUMNIST: MIKE BENNETT 18 Mike Bennett looks back on the Great l Britian tour of Australia in 1988. Which of TRACK PICTURES: KIRKMANSHULME LANE 20 the riders ended up in a swimming pool wearing full riding kit? Why were the riders LIVERPOOL: CRAVEN & THE CHADS 21 chased out of a shopping mall? The answers are in MB's column. COLUMNIST: CHRIS SEAWARD 23 We also feature an exclusive extract from Jeff Scott's brilliant travelogue - "Showered in Shale". This book has been described as a “printed documentary” and that's an excellent summary of the contents. -

Volume 12 No.3 December 2009 Edition No.47

The Speedway Researcher Promoting Research into the History of Speedway and Dirt Track Racing Volume 12 No.3 December 2009 Edition No.47 Constructive Debate Those of you who follow the Old Time Speedway chat room web site will know an article we published some time ago has been the cause of some, let us say, passionate, debate and questions about the accuracy of some of our articles. In the light of this we would like to say that we set up to achieve the sub heading above but never set up to make any claims about the accuracy of the material we publish simply because we cannot check every item we receive and publish. We accept, in good faith, that the article represents the honest belief of the contributor. Equally, that should anyone consider there are factual inaccuracies in any article that they let us know their differing opinion and we will publish it provided it is not going to land us in court i.e. isn‟t offensive to or is a personal attack on anyone. We would like to move on from this episode positively and, as a magazine which is nearing the half century edition, would like to see it continue to hit the 100, have everyone pulling together in pursuit of a common chequered flag. Keith Cox an original Edinburgh Monarch Tony Webb’s coverage of the lesser known lads continues. Keith Cox had a long career in Australia from 1946-1958, he ranks as one of the few Australian legends who never reached his true potential in Britain. -

Cradley Heath 1967 – Information Required

Cradley Heath Speedway 1967 Statistical Record Contents Index Of Meetings Meeting Details Nigel Nicklin & Roger Beaman – Issue 1 – 28th March 2014 Cradley Heath Speedway 1967 - Index Of Meetings Month Date Opponents Competition Venue Result For Agst Page March 24 Wolverhampton Challenge Away Lost 29 49 3 25 Wolverhampton Challenge Home Lost 36 41 4 28 Long Eaton British League Away Lost 28 50 5 April 1 Newport British League Home Lost 35 43 6 6 Sheffield British League Away Lost 27 48 7 8 Poole British League Home Won 40 37 8 13 Oxford British League Away Lost 27 51 9 15 Newcastle British League Home Lost 37 41 10 21 Hackney British League Away Lost 30 48 11 22 Long Eaton Knockout Cup Home Postponed - Rain 12 24 Newcastle British League Away Lost 38 40 13 29 Coventry British League Away Lost 22 56 14 May 1 Halifax British League Home Lost 36 42 15 6 Wolverhampton British League Home Won 41 37 16 8 Exeter British League Away Lost 24 54 17 13 World Champs QR Individual Home Ivor Brown 18 20 Sheffield British League Home Won 42 36 19 23 West Ham British League Away Lost 26 52 20 27 Swindon British League Home Won 46 31 21 June 3 Oxford British League Home Lost 38 39 22 5 Midland Riders QR Individual Home Rick France 23 10 Exeter British League Home Won 47 30 24 16 Newport British League Away Lost 22 55 25 17 Kings Lynn British League Home Won 39 38 26 19 Long Eaton Knockout Cup Home Lost 45 51 27 23 Wolverhampton British League Away Lost 27 51 28 24 Glasgow British League Home Lost 37 41 29 30 Glasgow British League Away Lost 32 46 30 July -

The Speedway Researcher

1 - but we shall not know until we make the effort ! How many people The Speedway Researcher are interested ? Who knows until we start ! Promoting Research into the History of Speedway and Dirt Track Racing I thought the launch of “The Speedway Researcher: would be an ideal Volume No.2 No.1 - June 1999 catalyst to get the project underway. To varying degrees I had started SUBSCRIBERS : 100 + working on 1939,1946 and 1947 seasons in “fits and starts”. That is why I have offered to do these seasons. Perhaps other enthusiasts THANKS FOR THE SUPPORT would consider doing other seasons ? What I need is people who can volunteer information to get in touch with me. Although I’ll be very The response to our second volume is very welcome and the response to our interested to have the details, the project is not for my personal benefit questionnaire is very heartening. We welcome the warm words of support and alone but hopefully will form an authoritative source of help for genuine it appears we are keeping most of our subscribers happy. We are particularly researchers in the future. delighted to read of new contacts being established and the helpful exchange Obviously there will be a number of matters to be considered if the of information. We are even more delighted to read of new research work project develops. Such as - How will the information be stored, being undertaken after The Speedway Researcher sparked off the work. presented and disseminated ? What about costs and charges ? Should We probably will never reach the 100 pages per edition asked for by one we aim for formal publications under “The Speedway Researcher” ? reader but we will add another four pages from the next edition onwards. -

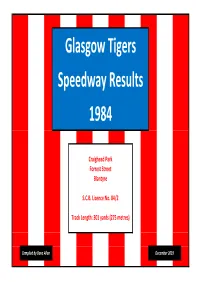

S Glasgow Tigers Speedway Results 1984

Glasgow Tigers S Speedway Results 1984 Craighead Park Forrest Street Blantyre S.C.B. Licence No. 84/2 Track Length: 301 yards (275 metres) Compiled by Dave Allan December 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks to the following: Steve Ashley Mark Aspinell Peter Colvin Neil Fife Alastair Fraser Mike Hunter Campbell Hutcheson Matt Jackson Gary Moore Gary Weldon Steve Wilkes The knowledgable members of the British Speedway Forum and the Easy, Tiger! Forum. CONTACT If you discover any inaccuracies, can provide missing details or have any information which you feel may benefit this file, please contact: [email protected] A list of main requirements can be found at the end of this file. REVISIONS - First Published August 2018 April 2019 - 24/05/1984 Arena-Essex v Glasgow: updated 2nd half details. April 2019 - 14/06/1984 Middlesbrough NL4TTQR: added junior match details. April 2019 - 15/06/1984 Edinburgh NL4TTQR: added junior match details. October 2019 - 09/09/1984 Mildenhall v Glasgow: added Glasgow #8 & 2nd half details. November 2019 - 19/04/1984 Middlesbrough v Glasgow: corrected Glasgow riding order, updated match heat details & added 2nd half details. December 2019 - 15/06/1984 Edinburgh NL4TTQR: updated match heat details, added reserve races details & corrected junior match details. December 2019 - 01/08/1984 Edinburgh v Glasgow: updated 2nd half details. December 2019 - 28/09/1984 Edinburgh v Glasgow: updated match & 2nd half heat details. THE FOLLOWING NOTATION IS IN USE THROUGHOUT THIS FILE SCORECHART HEAT DETAILS DESCRIPTION -

Cradley Heath 1966 Ver3 150418

Cradley Heath Speedway 1966 Statistical Record Contents Index Of Meetings Meeting Details Match Averages Nigel Nicklin & Roger Beaman ––– Issue 3 ––– 15th April 2018 Cradley Heath Speedway 1966 - Index Of Meetings Month Date Opponents Competition Venue Result For Agst Page March 26 Coventry British League Away Lost 28 50 3 April 1 Wolverhampton Challenge Away Lost 34 44 4 2 Coventry British League Home Lost 28 50 5 8 Swindon British League Away Lost 24 54 6 9 Newport British League Home Won 41 37 7 13 Poole British League Away Lost 35 42 8 16 Wimbledon British League Away Lost 32 45 9 18 Midland Riders QR Individual Home Postponed Rain 10 22 Glasgow British League Away Postponed Rain 11 23 Poole British League Home Lost 31 47 12 30 West Ham British League Home Lost 33 44 13 May 2 Midland Riders QR Individual Home Ron Mountford 14 3 West Ham British League Away Lost 29 48 15 7 Belle Vue British League Home Won 48 30 16 13 Wolverhampton Midland Cup Away Lost 34 44 17 14 Wolverhampton Midland Cup Home Lost 37 41 18 21 Swindon British League Home Won 39 38 19 28 World Champs QR Individual Home Ivor Brown 20 31 Long Eaton British League Away Lost 27 50 21 June 2 Oxford British League Away Lost 27 50 22 6 Alan Hunt Trophy Individual Home Barry Briggs 23 11 Belle Vue British League Away Lost 35 43 24 13 World Champs SF Individual Home Trevor Hedge 25 17 Hackney Knockout Cup 2Away Lost 47.5 48.5 26 18 Exeter British League Home Lost 33 39 27 24 Newport British League Away Lost 33 45 28 25 Kings Lynn British League Home Lost 34 43 29 July 1 Wolverhampton -

BRISTOL Needs Home

BRISTOL Needs Home Friday 26th July 1946 Knowle Stadium, Bristol Novice Championships SH Friday 30th August 1946 Knowle Stadium, Ex-Bristol 24 The Rest 36 Ht10 & Junior Race Friday 11th April 1947 Knowle Bristol Bulldogs 49 Birmingham Brummies 57 (Ch) Race Times Friday 25th April 1947 Knowle Bristol Bulldogs 39 Norwich Stars 44 (NLD2) Times Hts4&12 Friday 2nd May 1947 Knowle Bristol Bulldogs 47 Middlesbrough Bears 35 (NLD2) THt14 Friday 16th May 1947 Knowle Bristol Bulldogs 57.5 Glasgow Tigers 26.5 (NLD2)TSH2ndmen Friday 6th June 1947 Knowle Bristol British Riders’ Championship Qualifying Round THt20 Friday 29th August 1947 Knowle Bristol Bulldogs 38 Middlesbrough Bears 45 (NLD2) TSH2ndmen Friday 5th September 1947 Knowle Bristol Bulldogs 47 Wigan Warriors 36 (NLD2) TSH2ndmen Friday 19th September 1947 Knowle Bristol Bulldogs 64 Middlesbrough Bears 32 (BSC) TSH2ndmen Friday 26th September 1947 Knowle Bristol Bulldogs 51 Newcastle Diamonds 32 (NLD2) THt5 Friday26th March 1948Knowle Stadium,Bristol Bulldogs64EdinburghMonarchs 20 (NLD2)Times SH 2nds Friday 2nd April948 KnowleBristol Bulldogs65BirminghamBrummies 19(NLD2) Times Hts 3,4.8 SH Details Friday 9thApril 1948Knowle Stadium, Bristol Bulldogs 49 Middlesbrough Bears 35 (NLD2) Times SH 2nds Friday 16thApril 1948KnowleStadium, BristolBulldogs 57NewcastleDiamonds 27(NLD2)TSHFinal Friday23rdApril 1948 Knowle Stadium, Bristol Bulldogs71Edinburgh Monarchs 25 (AnnC) Times SH 2nds Friday 14th May 1948 Knowle Stadium,Bristol Bulldogs 61 Sheffield Tigers 23 (NLD2) Times SH 2nds Friday 21stMay1949KnowleStadium, -

STOKE 1960 Updated 11.5.2020 Updated

STOKE 1960 Updated 11.5.2020 Updated 26.9.2020 Friday 15th April 1960 Sun Street Stadium, Stoke Stoke Potters 44 Liverpool Pirates 26 (Provincial League) Stoke Ray Harris 3 3 3 3 12 Gordon Owen 0 2’ 2’ 2’ 6 3 Arthur Rowe 3 0 3 0 6 T ed Connor 1 1 1 3 Reg Fearman 2’ 2’ 3 X 7 2 Peter Kelly 3 3 1 3 10 Keith Rylance E 0 Liverpool Derek Skyner 1’ 2’ F F 3 2 Brian Craven 2 3 2 2 3 12 Dave Gerrard 2 X 1’ 2 1 Norman Murray E 1 1 2 Bert Edwards F 0 F 0 Roy Peacock 1 1 2 2’ 6 1 Sonny Dewhurst E 0 Ht1 Harris, Craven, Skyner, Owen 3 3 3 3 Ht2 Rowe, Gerrard, Connor, Murray (ef) 4 2 7 5 Ht3 Kelly, Fearman, Peacock, Edwards (f) 5 1 12 6 Ht4 Craven, Skyner, Connor, Rowe 1 5 13 11 Ht5 Kelly, Fearman, Murray, Gerrard (exc) 5 1 18 12 Ht6 Harris, Owen, Peacock, Edwards 5 1 23 13 Ht7 Fearman, Craven, Kelly, Skyner (f) 4 2 27 15 Ht8 Harris, Owen, Murray, Gerrard (ns) 5 1 32 16 Ht9 Rowe, Peacock, Connor, Edwards (f) 4 2 36 18 Ht10 Harris, Craven, Gerrard, Rowe 3 3 39 21 Ht11 Craven, Peacock, Rylance (ef), Fearman (exc) 0 5 39 26 Ht12 Kelly, Owen, Skyner (ef), Dewhurst (ef) 5 0 44 26 Reserves Race Johnny James, Alan Wright, Dewhurst, K.Rylance Nominated Riders Harris, Craven, Gerrard, Rowe Junior Trophy Ht1 Wright, Dewhurst, J.Rylance, Fred Collier Ht2 K.Rylance, Dennis Jenkins, Pat Byatt, Mike Lawrence Ht3 Key, Bill Davies, Ricky Smith, Les Perkins Ht4 James, Greenhalgh (nf), Ken Thompson (nf), L.Kirkham (nf) Final Wright, James, K.Rylance (nf), Key (nf) Monday 18th April 1960 Stanley Stadium, Liverpool Liverpool Pirates 32 Stoke Potters 37 (Provincial League) -

S Glasgow Tigers Speedway Results 1982

Glasgow Tigers S Speedway Results 1982 Craighead Park Forrest Street Blantyre S.C.B. Licence No. 82/applied for Track Length: 288 yards (263 metres) Compiled by Dave Allan May 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks to the following: Steve Ashley Mark Aspinell Richard Bills Peter Colvin Gary Done Neil Fife Robin Goodall Jim Henry Matt Jackson Richard Waller Gary Weldon Steve Wilkes The knowledgable members of the British Speedway Forum and the Easy, Tiger! Forum. CONTACT If you discover any inaccuracies, can provide missing details or have any information which you feel may benefit this file, please contact: [email protected] A list of main requirements can be found at the end of this file. REVISIONS - First published April 2019. August 2019 - 22/09/1982 Edinburgh v Glasgow: updated additional races heat details. November 2019 - 17/06/1982 Middlesbrough (4TT): added additional races heat details. November 2019 - 30/07/1982 Peterborough v Glasgow: added additional races heat details. November 2019 - Added Glasgow & Darvel Scottish Junior League averages. May 2020 - 16/08/1982 Scunthorpe v Glasgow: corrected heat details. May 2020 - 16/08/1982 Scunthorpe v Glasgow: added additional races heat details. THE FOLLOWING NOTATION IS IN USE THROUGHOUT THIS FILE SCORECHART HEAT DETAILS DESCRIPTION (guest) Rider making a ‘full and proper’ guest appearance (loanee) Rider drafted in from home or local track to make up a short-handed team (F) Rider scored a full maximum (see note A) (P) Rider scored a paid maximum (see note A) R/R Rider replacement -

SHEFFIELD Needs Updated 14.5.2015 Home

SHEFFIELD Needs Updated 14.5.2015 Home Thursday 18th April 1946 Owlerton Cup Time Ht 16 Thursday 25th April 1946 Sheffield Tigers 61 Glasgow Tigers 47 (National Trophy) SH Thursday 9th May 1946 Sheffield Tigers 63 Glasgow Tigers 44 (National Trophy) SH Thursday 30th May 1946 Owlerton, Sheffield Supporters’ Trophy Need 4th Placed + SH Thursday 20th June 1946 Owlerton, Sheffield 50 Guineas Trophy Time for Run Off Saturday 29th June 1946 Owlerton, Sheffield Sheffield Telegraph Cup SH Thursday 26th September 1946 Sheffield Tigers 51 Middlesbrough Bears 45 (ACU Cup) 4th placed men + second half Thursday 3rd October 1946 Sheffield E.Langton’s Team 40 J.Parker’s Team 44 (Chall) TSH2nd Men Thursday 10th October 1946 Owlerton, Sheffield Best Pairs 4th placed men + second half Thursday 17th April 1947 Sheffield Tigers 65 Wigan Warriors 19 (NLD2)Times 2nd placed men SH trophy heats Thursday 8th May 1947 Sheffield Best Pairs Details Ht4 Second Half Thursday 29th May 1947 Sheffield Tigers 56 Glasgow Tigers 40 (BSC) Need second half details Thursday 17th July 1947 Sheffield Tigers 60 Birmingham Brummies 24 (NLD2) Fastest second times Thursday 8th April 1948 Sheffield Tigers 55 Glasgow Tigers 28 (NLD2) SH Thursday 15th April 1948 Sheffield Tigers 48 Fleetwood Flyers 36 (NLD2) Det Stad Scr Fin Thursday 22nd April 1948 Sheffield Tigers 50 Birmingham Brummies 34 (NLD2) SH Thursday 6th May 1948 Sheffield Tigers 45 Middlesbrough Bears 39 (NLD2) SH Thursday 13th May 1948 Sheffield Tigers 45 Norwich Stars 39 (NLD2) TSH2ndmen + T SHFin Thursday 20th May 1948 -

Saturday 10Th April 1954 Old Meadowbank, Edinburgh

Saturday 10th April 1954 Old Meadowbank, Edinburgh Edinburgh Monarchs 47 Glasgow Tigers 36 (North Shield) Edinburgh Bob Mark E 3 2’ E 5 1 Eddie Lack 2 1’ 3 N 6 1 Don Cuppleditch 3 2 3 2 10 Bert Clark E 1 1 E 2 Dick Campbell 3 3 3 E 9 Jimmy Cox 2 3 2 0 7 1 Harry Darling 2’ 1 3 1 Jock Scott 3 2’ 5 1 Glasgow Larry Lazarus 1’ 2 2 2 7 1 Ken McKinlay 3 3 3 3 12 Alf McIntosh 2 0 0 1’ 3 1 Doug Templeton 1 E 1 1 3 Bob Sharp 1 2 1 2’ 6 1 Vern McWilliams E F X 3 3 Arthur Malm F F 0 Douglas Craig 1 1 2 Ht1 Cuppleditch, McIntosh, Lazarus, Mark (ef) 67.6 3 3 3 3 Ht2 McKinlay, Lack, Templeton, Clark (ef) 66.4* 2 4 5 7 Ht3 Campbell, Cox, Sharp, McWilliams (ef) 68.6 5 1 10 8 Ht4 Scott, Darling, Craig, Malm (f) 70.8 5 1 15 9 Ht5 Mark, Lazarus, Clark, Templeton 71.0 4 2 19 11 Ht6 Campbell, Sharp, Darling, Malm (f) 71.6 4 2 23 13 Ht7 McKinlay, Cuppleditch, Lack, McIntosh 66.6 3 3 26 16 Ht8 Cox, Scott, Craig, McWilliams (f) 70.4 5 1 31 17 Ht9 Lack, Lazarus, Clark, McIntosh 72.0 4 2 35 19 Ht10 McKinlay, Cox, Templeton, Campbell (ef) 68.4 2 4 37 23 Ht11 Cuppleditch, Mark, Sharp, McWilliams (exc) 68.0 5 1 42 24 Ht12 Campbell, Lazarus, McIntosh, Cox 69.4 3 3 45 27 Ht13 McWilliams, Sharp, Lack (nf), Clark(ef) 74.4 0 5 45 32 Ht14 McKinlay, Cuppleditch, Templeton, Mark (ef) 68.0 2 4 47 36 Wednesday 14th April 1954 White City Stadium, Glasgow Glasgow Tigers 32 Coventry Bees 51 (North Shield) Gasgow Ken McKinlay 3 2 3 3 11 Doug Templeton 0 0 2’ 0 2 1 Larry Lazarus 0 3 1 3 7 Alf McIntosh 1 0 0 1 2 Bob Sharp E E 2 2 4 Vern McWilliams 1 2 0 3 Arthur Malm 1 2 0 3 Douglas -

Volume 5 No.3

The Speedway Researcher Promoting Research into the History of Speedway and Dirt Track Racing Volume 5 No. 3 December 2002 Edited by Graham Fraser and Jim Henry Subscribers : 160 Who Was The Best Prewar Rider? Don Gray, Old Orchard, Waterbeach, Cambridgeshire, CB5 9JU, Telephone: 01223 862279 has posed the question above and set out to answer it in the following article. On becoming aware that I saw my first speedway meeting on Easter Monday 1930, many acquaintances ask, who, in my opinion, was the best rider in the pre-war era? A most difficult question to answer. A number of criteria present themselves from which to reach an opinion and they are viewed from different perspectives by various enthusiasts, many of whom, I might suggest, are biased towards their own particular favourites. I must concentrate on the thirties and ignore the overseas pioneers of the late 1920s when Frank Arthur and Vic Huxley reigned supreme over the inexperienced emergent British riders and when those spectacular showmen like Billy Lamont and Sprouts Elder enthralled a curious and excited public. I choose to ignore the one track specialists who performed brilliantly on their own circuits but indifferently when visiting other tracks. I put men like Jack Barnett and Phil Bishop at High Beech, the Australian Jack Bishop at Exeter, Arthur Jervis at Leicester Super and Len Parker at Bristol. Unlike the modern era, the pre-war decade was notable for the number of riders who experienced purple patches of form and dominated their peer for a few weeks, only to recede back to the category of “good” rather than “outstanding”.