Digital Media in Refugees' Everyday Life and Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magazine Collection

Magazine Collection American Craft Earth Magazine Interweave Knits American Patchwork and Quilting Eating Well iPhone Life American PHOTO Elle Islands American Spectator Elle DÉCOR Kiplinger’s Personal Finance AppleMagazine Equs La Cucina Italiana US Architectural Record ESPN The Magazine Ladies Home Journal Astronomy Esquire Living the Country Life Audubon Esquire UK Macworld Backcountry Magazine Every Day with Rachel Ray Marie Claire Backpacker Everyday Food Martha Stewart Living Baseball America Family Circle Martha Stewart Weddings Bead Style Family Handyman Maxim Bicycle Times FIDO Friendly Men’s Fitness Bicycling Field & Stream Men’s Health Bike Fit Pregnancy Mental Floss Bloomberg Businessweek Food Network Magazine Model Railroader Bloomberg Businessweek-Europe Forbes Mother Earth News Boating Garden Design Mother Jones British GQ Gardening & Outdoor Living Motor Trend Canoe & Kayak Girls’ Life Motorcyclist Car and Driver Gluten-Free Living National Geographic Clean Eating Golf Tips National Geographic Traveler Climbing Good Housekeeping Natural Health Cloth Paper Scissors GreenSource New York Review of Books Cosmopolitan Newsweek Grit Cosmopolitan en Espanol O the Oprah Magazine Guideposts Country Living OK Magazine Guitar Player Cruising World Organic Gardening Harper’s Bazaar Cycle World Outdoor Life Harvard Business Review Diabetic Living Outdoor Photographer HELLO! Magazine Digital Photo Outside Horse & Rider Discover Oxygen House Beautiful Dressage Today Parenting Interweave Crochet HARFORD COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY Magazine -

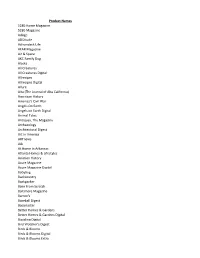

Product Names 5280 Home Magazine 5280 Magazine Adage Additude

Product Names 5280 Home Magazine 5280 Magazine AdAge ADDitude Adirondack Life AFAR Magazine Air & Space AKC Family Dog Alaska All Creatures All Creatures Digital Allrecipes Allrecipes Digital Allure Alta (The Journal of Alta California) American History America's Civil War Angels On Earth Angels on Earth Digital Animal Tales Antiques, The Magazine Archaeology Architectural Digest Art In America ARTnews Ask At Home In Arkansas Atlanta Homes & Lifestyles Aviation History Azure Magazine Azure Magazine Digital Babybug Backcountry Backpacker Bake From Scratch Baltimore Magazine Barron's Baseball Digest Bassmaster Better Homes & Gardens Better Homes & Gardens Digital Bicycling Digital Bird Watcher's Digest Birds & Blooms Birds & Blooms Digital Birds & Blooms Extra Blue Ridge Country Blue Ridge Motorcycling Magazine Boating Boating Digital Bon Appetit Boston Magazine Bowhunter Bowhunting Boys' Life Bridal Guide Buddhadharma Buffalo Spree BYOU Digital Car and Driver Car and Driver Digital Catster Magazine Charisma Chicago Magazine Chickadee Chirp Christian Retailing Christianity Today Civil War Monitor Civil War Times Classic Motorsports Clean Eating Clean Eating Digital Cleveland Magazine Click Magazine for Kids Cobblestone Colorado Homes & Lifestyles Consumer Reports Consumer Reports On Health Cook's Country Cook's Illustrated Coral Magazine Cosmopolitan Cosmopolitan Digital Cottage Journal, The Country Country Digital Country Extra Country Living Country Living Digital Country Sampler Country Woman Country Woman Digital Cowboys & Indians Creative -

1. Eva Dahlbeck - “Pansarskeppet Kvinnligheten”

“Pansarskeppet kvinnligheten” deconstructed A study of Eva Dahlbeck’s stardom in the intersection between Swedish post-war popular film culture and the auteur Ingmar Bergman Saki Kobayashi Department of Media Studies Master’s Thesis 30 ECTS credits Cinema Studies Master’s Programme in Cinema Studies 120 ECTS credits Spring 2018 Supervisor: Maaret Koskinen “Pansarskeppet kvinnligheten” deconstructed A study of Eva Dahlbeck’s stardom in the intersection between Swedish post-war popular film culture and the auteur Ingmar Bergman Saki Kobayashi Abstract Eva Dahlbeck was one of Sweden’s most respected and popular actresses from the 1940s to the 1960s and is now remembered for her work with Ingmar Bergman, who allegedly nicknamed her “Pansarskeppet kvinnligheten” (“H.M.S. Femininity”). However, Dahlbeck had already established herself as a star long before her collaborations with Bergman. The popularity of Bergman’s three comedies (Waiting Women (Kvinnors väntan, 1952), A Lesson in Love (En lektion i kärlek, 1954), and Smiles of a Summer Night (Sommarnattens leende, 1955)) suggests that they catered to the Swedish audience’s desire to see the star Dahlbeck. To explore the interrelation between Swedish post-war popular film culture and the auteur Bergman, this thesis examines the stardom of Dahlbeck, who can, as inter-texts between various films, bridge the gap between popular film and auteur film. Focusing on the decade from 1946 to 1956, the process whereby her star image was created, the aspects that constructed it, and its relation to her characters in three Bergman titles will be analysed. In doing so, this thesis will illustrate how the concept “Pansarskeppet kvinnligheten” was interactively constructed by Bergman’s films, the post-war Swedish film industry, and the media discourses which cultivated the star cult as a part of popular culture. -

Syrian Diaspora Groups in Europe: Mapping Their Engagement in Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom

, 5th December 2018 Syrian Diaspora Groups in Europe: Mapping their Engagement in Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom → Danish Refugee Council © Jwan Khalaf Study background and objectives This research was commissioned by Danish Refugee Council’s (DRC) Diaspora Programme as part of a project with the Durable Solutions Platform (DSP) joint initiative of DRC, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC). This study seeks to explore Syrian diaspora mobilisation in six European host countries: Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. The report focuses on the organisational framework, transnational links and practices of Syrian diaspora groups, by taking into account both internal dynamics and potential lines of conflict as well as the contextual factors in the country of origin and destination. The mapping and study seek to provide a basis for further engagement with the most relevant group of Syrians (associations and individuals) across Europe for consultations on future solution scenarios for Syrian refugees, as well as to enable DRC’s Diaspora Programme to develop activities specifically targeting the Syrian diaspora looking towards the reconstruction and development of Syria. Key findings Altogether, Syrians in Europe mirror to some extent the situation in Syria, and their heterogeneity has become even more pronounced after 2011, politically, economically and ethnically. The Syrian uprising in 2011 can be perceived as a transformative event that politicised Syrians abroad and sparked collective action aiming to contribute to the social and political transformations happening in the country. Besides, the escalation of the conflict and increasing numbers of Syrians seeking protection in Europe have led to further mobilisation efforts of the diaspora, who try to alleviate the suffering of the Syrian people both at home and abroad. -

New Civil Status Law Raises Concerns Over Identity Cards and HLP Rights

Inside >> No. 10 MSF Suspends Danish Immigration Damascus Declares Telecom Trouble as Activities in Wake Authorities Strip 94 Russia Will Provide MTN Comes into of Deadly Fire in Syrian Refugees of Wheat Aid (Again) Asma Al-Assad’s ‘Unsafe’ Al-Hol Camp Residency Permits Past wheat aid from Orbit Security deterioration Denmark is the first Russia has frequently The fate of Syria’s prompts MSF to EU country to deem fallen short second-largest provider temporarily halt aid in Damascus safe Pg 6 is evidence of the First the camp for return Lady’s ambitions Pg 5 Pg 6 Pg 7 8 March 2021 | Vol. 4 | 8 March 2021 | Vol. Russia Destroys After Tafas Self-Administration ‘Cave’ Hospital in Meeting, Louka Announces Plan to Hama’s Kafr Zeita Agrees to Release Divide Deir-ez-Zor The ‘most secure health 30 Detainees into 4 Cantons facility in Syria’ is Detainee releases The move is important, demolished are good PR before but its potential impact Pg 7 upcoming elections is less certain date Pg 8 Pg 9 New Civil Status Law Raises Concerns Over Identity Cards and HLP Rights > Page 2 Syria Up Weekly Political, Economic, and Security Outlook Political, Weekly Syrian parliament approves new Civil Status Law. Source: Syrian Panorama 02 Syria Update | In-Depth Analysis n 1 March, the Syrian People’s Assembly updated >the nation’s Civil Status Law. AlthoughO the update can be seen as a procedural refresher, it has sparked concerns inside Syria and abroad that it will leave Syrians without the means of renewing critically important national ID cards unless they can physically enter Government of Syria areas. -

Afghan Diaspora in Europe Mapping Engagement in Denmark, Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom

Afghan Diaspora in Europe Mapping engagement in Denmark, Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom diaspora programme Acknowledgements This study was commissioned by Danish Refugee Council, as part of a larger project to support Afghan diaspora engagement in Europe and was carried out by Maastricht Graduate School of Governance/ UNU-MERIT. The report has been written by Dr. Biljana Meshkovska, Nasrat Sayed, Katharina Koch, Iman Rajabzadeh, Carole Wenger, and Prof. Dr. Melissa Siegel. Editing was conducted by Emily Savage, from Meraki Labs. We would like to thank Maximilian Eckel, Nina Gustafsson, Rufus Horne, Helle Huisman, Chiara Janssen, Bailey Kirkland, Charlotte Mueller, Kevin O’Dell, Wesal Ah. Zaman, and Gustaf Renman for their invaluable support in this research. Moreover, we thank all respondents for sharing their insights with us. Danish Refugee Council’s Diaspora Programme The Diaspora programme is part of DRC’s Civil Society Engagement Unit, and focuses on facilitating, supporting, and enhancing the role of diasporas as effective agents of humanitarian assistance, recovery and development. DRC is a private, independent, humanitarian organization working in more than 35 countries to protect refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) against persecution and to promote durable solutions to the problems of forced displacement based on humanitarian principles and human rights. Contact: [email protected] Website: drc.ngo/diaspora Asia Displacement Solutions Platform The Asia Displacement Solutions Platform is a joint initiative launched by the Danish Refugee Council, International Rescue Committee, Norwegian Refugee Council and Relief International, which aims to contribute to the development of solutions for populations affected by displacement in the region. Drawing upon its members’ operational presence throughout Asia, and its extensive advocacy networks in Europe and North America, ADSP engages in evidence-based advocacy initiatives to support improved outcomes for displacement-affected communities. -

The Future of Education, Including the Importance of the Affective

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 197 074 CE 027 573 AUTHOR Spitze, Hazel Taylor, Ed. TITLE Proceedings of the Conference on Current Concerns in Home Economics Education (Champaign, Illinois, April 16-19, 1973). INSTITUTION Illinois Univ., Urbana. Dept. of Vocational and Technical Education. PUB DATE Apr. 78 NOTE 73p. AVAILABLE FROM Illinois Teacher, College of Education, University of Illinois, 1310 S. 6th St., Champaign, IL 61820 ($2.00: $1.00, 100 or more copies). EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCPIPTO"RS *Educational Needs: Educational Objectives; Educational Philosophy: *Educational Planning: Futures (of Society): *Home Economics; *Home Economics Education: Legislation; *Policy Formation: Postsecondary Education: Professional Associations: Professional Development: Professional Education; Professional Recognition: Reputation; Secondary Education: *Social Problems: Status IDENTIFIERS *Social Impact: *Societal Needs ABSTRACT Participants in a conference held in April, 1978, had four main objectives: (1) to help identify and become more aware of the current concerns in home economics education: (2) to value the role of home economics education in promoting needed social change: (3) to contribute during the conference to the generation of possible solutions and actions to be taken regaIding current social problems; and (4) to make plans and feel committed to share the conference with others in their home state or region. To accomplish these objectives, speakers, beggining with keynote speaker Marjorie East, focused on issues such as the profession of home economics and how to build it: the future of education, including the importance of the affective domain, the accountability movement, and the National Institute of Education evaluation of consumer and homemaking education; and needs in secondary home economics education programs in the 1980s. -

Dansksimulatoren Danish Simulator Vejle (Denmark)

Dansksimulatoren Danish Simulator Vejle (Denmark) EU-MIA RESEARCH REPORT Ole Jensen COMPAS January 2014 www.itcilo.org Dansksimulatoren Danish Simulator Vejle (Denmark) EU-MIA RESEARCH REPORT Ole Jensen COMPAS January 2014 The materials in this publication are for information purposes only. While ITCILO, FIERI and COMPAS endeavour to ensure accuracy and completeness of the contents of this publication, the views, findings and content of this discussion paper are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect the official position of ITCILO, FIERI and COMPAS. © 2013 International Training Centre of the ILO in Turin (ITCILO) Forum Internazionale ed Europeo di Ricerche sull’Immigrazione (FIERI) Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS), University of Oxford This discussion paper is financed by the European Commission and published in the context of the project “An integrated research and cooperative learning project to reinforce integration capacities in European Cities-EU-MIA, EC Agreement Nr HOME/2011/EIFX/CA/1996”. The content of this discussion paper does not reflect the official opinion of the European Commission. Index 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 6 2. Operational Context ................................................................................................. 7 2.1 Key characteristics: demographic mix, socio-economic indicators and main challenges ............. 7 2.2 Policy context .................................................................................................. -

WEYV Announces Partnership with Bonnier Corporation, Expands In-App Magazine Options

WEYV Announces Partnership with Bonnier Corporation, Expands In-App Magazine Options April 24, 2018 Troy, Michigan, April 24, 2018 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- WEYV, an app platform with music, magazines and more all in one app experience, today announced its partnership with Bonnier Corp., one of the largest special interest-publishing groups in America. WEYV – Music, magazines and more all in one app WEYV is an entertainment app with music, magazines and (soon) TV shows and podcasts all in one app experience Through this partnership, WEYV will now offer 17 new magazines in the app, including Boating, Cruising World, Cycle World, Field & Stream, Flying, Hot Bike, Marlin, Motorcyclist, Outdoor Life, Popular Science, Sailing World, Salt Water Sportsman, Saveur, Scuba Diving, Sport Fishing, Working Mother and Yachting. The inclusion of these special-interest titles is in direct response to WEYV users seeking additional magazine options. “As a start-up, it is critical that we listen to the requests from our customers. While WEYV already offered a healthy mix of lifestyle, trade and business magazines in the app, it was clear there was a need for additional content focused on specific interests,” said Stephanie Scapa, CEO of WEYV. “Partnering with Bonnier Corp., one of the leading special-interest publishers in the country, was an obvious and natural next step to diversify the content we offer to our users.” WEYV is available as an ad-free, subscription-based app that allows users to listen to music, read magazines and (soon) watch visual content. WEYV is available on iOS and Android devices and via a web player for U.S.-based users. -

BONNIER ÅRSREDOVISNING Innehåll

1 2019BONNIERS ÅRSBERÄTTELSE 2019 BONNIER ÅRSREDOVISNING Innehåll Förvaltningsberättelse 3 Koncernens resultaträkningar 9 Koncernens rapporter över totalresultat 9 Koncernens rapporter över finansiell ställning 10 Koncernens rapporter över förändringar i eget kapital 12 Koncernens rapporter över kassaflöden 13 Koncernens noter 14 Moderföretagets resultaträkningar 44 Moderföretagets rapporter över totalresultat 44 Moderföretagets balansräkningar 45 Moderföretagets rapporter över förändringar i eget kapital 46 Moderföretagets rapporter över kassaflöden 46 Moderföretagets noter 47 Revisionsberättelse 57 Flerårsöversikt 59 bonnier ab årsredovisning 2019 2 Förvaltningsberättelse Styrelsen och verkställande direktören för Bonnier AB, organi- Utveckling av verksamhet, ställning och sationsnummer 556508-3663, avger härmed årsredovisning och resultat (Koncernen) koncernredovisning för räkenskapsåret 2019 på sidorna 3-58. (Belopp i Mkr om ej annat anges) 2019 2018 Intäkter 20 227 18 307 Koncernens verksamhet EBITA1) 9 -410 Bonnier AB är moderbolag i en mediekoncern med bolag verksam- Rörelseresultat -83 -1 439 ma inom tv, dagstidningar, affärs- och fackmedier, tidskrifter, film, Finansnetto -49 -158 böcker, e-handel och digitala medier och tjänster. Koncernen har Resultat före skatt -132 -1 597 verksamhet i 12 länder med bas i de nordiska länderna och verksam- Årets resultat 2 813 -872 heter i bland annat USA, Tyskland, Storbritannien och Östeuropa. EBITA-marginal 0,0% -2,2% Koncernens intäkter kommer från två huvudsakliga kategorier; Räntabilitet på operativt kapital -0,9% n/a dels användarintäkter från konsumenter och B2B-kunder i form Nettoskuld vid årets slut av prenumerationer, styckvisa köp och event, dels annonsintäkter 776 7 743 från framför allt digitala medietjänster, linjär-tv samt printannon- Relation nettoskuld dividerat med eget kapital 0,14 2,12 sering. De största externa leverantörskategorierna finns inom rättig- Bolag hetsinköp, tryckeri, böcker och andra varor till försäljning genom Intäkter per Bolag e-handel, samt IT. -

5. Yilinda Avrupa Birliği-Türkiye Mutabakati

5. YILINDA AVRUPA BİRLİĞİ-TÜRKİYE MUTABAKATI 5. YILINDA AVRUPA BİRLİĞİ – TÜRKİYE MUTABAKATI Proje Koordinatörü: Didem Danış Proje Asistanı: Ekin Ürgen Video Montaj: Buse Akkaya Rapor Tasarımı: Zeynep Ürgen İdari Asistan: Fırat Çoban Göç Araş?rmaları Derneği (GAR) Abbasağa Mahallesi, Üzengi Sok. No: 13 34353, Beşiktaş / İstanbul https://www.gocarastirmalaridernegi.org/tr/ [email protected] hVps://twiVer.com/GAR_Dernek hVps://www.facebook.com/gar.dernek/ Göç Araş?rmaları Derneği - GAR © Tüm hakları saklıdır. İzin almaksızın çoğal?labilir. Referans vermeden kullanılmaz. GAR-Rapor No.5 ISBN: 978-605-80592-5-2 Nisan 2021 A?f için bkz. GAR (2021). 5. Yılında Avrupa Birliği - Türkiye Mutabaka?. GAR - Rapor No. 5. Bu proje Heinrich Böll Shiung Derneği Türkiye Temsilciliğinin desteğiyle gerçekleşhrilmişhr. Bu çalışmada belirhlen görüşler, bütünüyle yazarlara air. Göç Araş?rmaları Derneği (GAR) ve Heinrich Böll Shiung (HBS) Derneği'nin görüşlerini yansıtmamaktadır KISALTMALAR AB/EU Avrupa Birliği / European Union AfD Alternahve für Deutschland BM Birleşmiş Milletler CDU Hrishyan Demokrat Parh ESI European Stability Iniahve ESSN Acil Sosyal Güvenlik Ağı / Emergency Social Safety Net FRIT Türkiye’deki Sığınmacılar için Mali Yardım Programı / The EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey GİGM Göç İdaresi Genel Müdürlüğü GKS Geçici Koruma Statüsü IS Islamic State NGO Non-Governmental Organizahon / Hükümetdışı kuruluşlar PIKTES Suriyeli Çocukların Türk Eğihm Sistemine Entegrasyonunun Desteklenmesi Projesi SIHHAT FRIT Kapsamında Suriyeli Mültecilere Sunulan Sağlık Hizmetlerini Gelişhrmeyi Amaçlayan Proje SPD Sosyal Demokrat Parh UNHCR/ BMMYK Birleşmiş Milletler Mülteciler Yüksek Komiserliği YUKK Yabancılar ve Uluslararası Koruma Kanunu 4 İÇİNDEKİLER ÖNSÖZ 6 ARKA PLAN: 5. YILINDA AB-TÜRKİYE MUTABAKATI 7 EKİN ÜRGEN DIŞSALLAŞTIRMA – ARAÇSALLAŞTIRMA SARKACINDA 14 AB-TÜRKİYE MUTABAKATININ 5. -

Impact of Humanities Research: 24 Case Studies

August 2017 IMPACT OF HUMANITIES RESEARCH: 24 CASE STUDIES Interest in research impact – the contribution research makes to society – continues to grow in Denmark and abroad. The cases presented here by the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Copenhagen illustrate how research can, in a number of ways, make important contributions to social, cultural and political developments. Society benefits from humanities research, whether conducted by universities in collaboration with external partners such as private companies or government agencies, or carried out using a more traditional approach. The knowledge generated is transferred to society in numerous formal and informal ways through verbal and written communication, business collaborations, networking, continuing education, public-sector services, etc. – not forgetting the enormous value represented by the knowledge and competencies of our graduates, of course. With these detailed case studies the Faculty of Humanities wishes to illustrate the value of the multiple contributions made by our researchers, including areas where the impact of their work cannot be quantified in straightforward terms such as ‘the number of patents taken out’. The impact of humanities research ranges across subjects as varied as the following: • Development of a dyslexia test for all school levels • More sustainable urban development • Enhanced communication with aphasia patients • Streamlining emergency aid by improving the flow of information, and • Improved understanding of culture and religion in the Middle East The impact cases presented here thus demonstrate the diversity of timely, relevant and innovative research subjects and methods in the humanities. Have a good read! Ulf Hedetoft Dean, Professor dr.phil. WHAT MAKES A Christina Fogtmann Fosgerau GOOD CONVERSATION? Associate Professor Communication between doctor and patient is crucial for correct diagnosis and for planning the right treatment.