University of Huddersfield Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glory to the Father, the Son, and the Holy

Saint John Gualbert Cathedral PO Box 807 Johnstown Glory to the Father, 15907-0807 the Son, and the Office Holy Spirit; 539-2611 536-0117 to God who is, who was, Cemetery and who is to come. 536-0117 FAX 536-6771 Sunday May 30 Solemnity of the Most Holy Trinity Readings: Deuteronomy 4:32-34, 39-40 / Romans 8:14-17 / Matthew 28:16-20 8:00 am Peter Vizza Birthday Celebration (Friends & Family) [email protected] 11:00 am Proclaim TV Ministry Mass 5:00 pm People of the Parish Most Rev Bishop Monday May 31 Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary Mark L. Bartchak, JDC Readings: Zephaniah 3:14-18a / Luke 1:39-56 9:00 am Louise Aust (Lou & Lea Aust) Mass @ St. Benedict’s Rector & Pastor Very Rev James F. Crookston Tuesday June 1 St. Justin, Martyr Readings: Sirach 35:1-12 / Mark 10:28-31 7:00 am Michael Serafin, Sr. Anniversary June 2nd (Family) SUNDAY LITURGIES 12:05 pm Deacon John Concannon Anniv. of Ordination (Family) Saturday Evening 5:00 pm th Wednesday June 2 Wednesday of the 9 Week of Ordinary TIme Sundays Readings: Tobias 3:1-11a, 16-17a / Mark 12:18-27 8:00 am 7:00 am Jack Leonard Birthday Remembrance (Wife & Family) 11:00 am 12:05 pm Deceased Members of Woefel Family (Dianne O’Shea) 5:00 pm Thursday June 3 St. Charles Lwanga & Companions, Martyrs OUTDOOR COMMUNION Readings: Tobias 6:10-11; 7:1bcde, 9-17; 8:4-9a / Mark 12:28-34 Wedding Anniversary June 2 Sundays 7:00 am Eugene Ritter (Irene Ritter) 12:05 pm Irene Yanko (George Kopach Family) 12:30-1:00 pm St John Activities Center th Friday June 4 Friday of the 9 Week of Ordinary TIme DAILY MASS Readings: Tobias 11:5-17 / Mark 12:35-37 Monday through Friday 7:00 am St. -

Backlash: Defiance, Human Rights and the Politics of Shame By

Backlash: Defiance, Human Rights and the Politics of Shame By Rochelle Layla Terman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and the Designated Emphasis in Gender and Women’s Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ron E Hassner, Chair Professor Jason Wittenberg Professor Steven Weber Professor Raka Ray Summer 2016 Backlash: Defiance, Human Rights and the Politics of Shame Copyright 2016 by Rochelle Layla Terman Abstract Backlash: Defiance, Human Rights and the Politics of Shame by Rochelle Layla Terman Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Ron E Hassner, Chair This dissertation examines the causes and consequences of international “naming and shaming”: a ubiquitous tactic used by states and civil society to improve interna- tional human rights. When does international shaming lead to the improvement in hu- man rights conditions, and when does it backfire, resulting in the worsening of human rights practices or a backlash against international norms? Instead of understanding transnational norms as emanating from some monolithic “international community,” I propose that we gain better analytic insight by considering the ways in which norms are embodied in particular actors and identities, promoted and contested between specific states in relational terms. Starting from this approach, I apply insights from sociology, social psychology, and criminology to develop a theory of international “defiance,” or the increase in norm offending behavior caused by a proud, shameless reaction against a sanctioning agent. As detailed in Chapter 2, defiance unfolds through domestic and international logics that incentivize elites to violate international norms for political gain. -

Diasporic Iranian Women's Life Writing: an Analysis Using A

Diasporic Iranian Women’s Life Writing: An Analysis Using a Transnational Feminist Lens Farida Abla A Thesis In the Department of Humanities Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Humanities) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2020 © Farida Abla, 2020 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Farida Abla Entitled: Diasporic Iranian Women Life Writing: An Analysis Using a Transnational Feminist Lens and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Humanities) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Viviane Namaste External Examiner Dr. Eva Karpinski External to Program Dr. Rachel Berger Examiner Dr. Homa Hoodfar Examiner Dr. Sarah Ghabrial Thesis Supervisor Dr. Gada Mahrouse Approved by _____________________________________________ Dr. Marcie Frank, Graduate Program Director ________, 2020 _____________________________________________ Dr. Pascale Sicotte, Dean of Faculty of Arts and Science ABSTRACT Diasporic Iranian Women’s Life Writing: An Analysis Using a Transnational Feminist Lens Farida Abla, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2020 This thesis examines fourteen diasporic life writing in English by Iranian women who mainly reside in North America (the United States and Canada), with a particular interest in how and why they write about their lives. The women authors bring to the fore questions of home, nation, identity and belonging in narratives where the public and the political are deeply intertwined with the personal. The thesis provides an analysis of the authors’ responses to the events that impacted their lives, their use of English, and their dynamic process of identity construction, as manifested in their narratives. -

Reading Muslim Women: the Cultural Significance of Muslim Women‟S Memoirs

READING MUSLIM WOMEN: THE CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF MUSLIM WOMEN‟S MEMOIRS by Nicole Fiore Department of Integrated Studies in Education McGill University, Montreal October 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts in Education © Nicole Fiore 2010 ii Abstract This study looks at a growing trend in literature: memoirs written by women from Islamic countries. It will deal specifically with the cultural significance of these books in North American culture with special consideration of how the Muslim religion is depicted and therefore relayed to the North American audience. Finally, this paper will look at how these memoirs, and other texts like them, can be used in the classroom to teach against Islamophobia. Cette étude porte sur une tendance de plus en plus importante dans la littérature contemporaine, celles des mémoires écrits par les femmes des pays islamiques. Plus précisement, cette étude se penche sur la portée culturelle de ces livres dans la culture nord-américaine. Une attention particulière est porté à la façon dont la religion musulmane est représentée et, par conséquent, relayée au grand public nord-américain. Enfin, ce document examinera comment ces mémoires et d'autres similaires peuvent être utilisés en classe pour sensibiliser les élèves aux dangers de l'islamophobie. iii Acknowledgements Thank you to all those who stood by me throughout the years, especially Shirley R. Steinberg. Without her patience and guidance this paper would not have been possible. To all those who assisted me right up until the very end, especially Kristin Gionfriddo whose advice I am truly thankful for. -

The Media, Human Rights and Iran

Iran Media-Monitoring Study 1 July–30 September 2007 By Victor Kattan* This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication is the sole responsibility of BIICL and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. * The author is a Research Fellow at the British Institute of International and Comparative Law. He would like to thank Amir Nakhjavani for his assistance in preparing the chapter on the Iranian media. 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 2. Summary of Findings........................................................................................................... 5 3. The Media Monitoring Study ............................................................................................... 6 3.1 Scope of Study................................................................................................................ 6 3.2. The Media in Iran ........................................................................................................... 6 3.3 Important Developments ................................................................................................. 7 4. The Media, Human Rights and Iran.................................................................................... 8 4.1 Right to Life/Enforced Disappearances .......................................................................... 8 4.2 Torture, -

Prisoner of Tehran: a Personal Journey Through Family History

PRISONER OF TEHRAN: A PERSONAL JOURNEY THROUGH FAMILY HISTORY RAHA SHIRAZI A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES FOR THE PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN FILM YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO DECEMBER 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-88653-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-88653-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Working with People Who Have Experienced State Violence

THE ART OF REMEMBERING: IRANIAN POLITICAL PRISONERS, RESISTANCE AND COMMUNITY by Bethany J. Osborne A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Leadership, Higher and Adult Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Bethany J. Osborne 2014 The Art of Remembering: Iranian Political Prisoners, Resistance and Community Bethany J. Osborne Doctor of Philosophy, 2014 Department of Leadership, Higher and Adult Education University of Toronto ABSTRACT Over the last three decades, many women and men who were political prisoners in the Middle East have come to Canada as immigrants and refugees. In their countries of origin, they resisted oppressive social policies, ideologies, and various forms of state violence. Their journeys of forced migration/exile took them away from their country, families, and friends, but they arrived in Canada with memories of violence, resistance and survival. These former political prisoners did not want the sacrifices that they and their colleagues had made to be forgotten. They needed to find effective ways to communicate these stories. This research was conducted from a critical feminist‒anti-racist perspective, and used life history research to trace the journey of one such group of women and men. This group of former political prisoners has been meeting together, using art as a mode of expression to share their experiences, inviting others to join their resistance against state violence. Interviews were conducted with former political prisoners and their supporters and artist facilitators who were part of the art workshops, performances, and exhibits held in Toronto, Canada from January 2010 through December 2011. -

One Woman's Story of Survival Inside an Iranian Prison Marina Nemat

[pdf] Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison Marina Nemat - free pdf download Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison by Marina Nemat Download, Read Online Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison E-Books, I Was So Mad Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison Marina Nemat Ebook Download, Free Download Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison Full Version Marina Nemat, Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison Free Read Online, full book Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison, online free Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison, online pdf Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison, Download PDF Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison Free Online, read online free Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison, by Marina Nemat pdf Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison, Download Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison E-Books, Read Online Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison Book, Read Online Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison E-Books, Read Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison Full Collection, Read Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison Book Free, Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison pdf read online, Free Download Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison Best Book, Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison Free PDF Online, PDF Download Prisoner Of Tehran: One Woman's Story Of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison Free Collection, CLICK FOR DOWNLOAD I found it 71 's. -

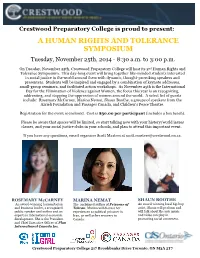

A Human Rights and Tolerance Symposium

Crestwood Preparatory College is proud to present: A HUMAN RIGHTS AND TOLERANCE SYMPOSIUM Tuesday, November 25th, 2014 - 8:30 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. On Tuesday, November 25th, Crestwood Preparatory College will host its 2nd Human Rights and Tolerance Symposium. This day-long event will bring together like-minded students interested in social justice in the world around them with dynamic, thought-provoking speakers and presenters. Students will be inspired and engaged by a combination of keynote addresses, small-group seminars, and facilitated action workshops. As November 25th is the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, the focus this year is on recognizing, addressing, and stopping the oppression of women around the world. A select list of guests include: Rosemary McCarney, Marina Nemat, Shaun Boothe, a groups of speakers from the Azrieli Foundation and Passages Canada, and Children's Peace Theatre. Registration for the event is enclosed. Cost is $30.00 per participant (includes a box lunch). Please be aware that spaces will be limited, so start talking now with your history/world issues classes, and your social justice clubs in your schools, and plan to attend this important event. If you have any questions, email organizer Scott Masters at [email protected]. ROSEMARY McCARNEY MARINA NEMAT SHAUN BOOTHE An award-winning humanitarian The acclaimed author of Prisoner of An award winning local hip hop and business leader, a recognized Tehran, Marina will discuss her artist, Shaun will perform and public speaker and author and an experiences as political prisoner in will talk about the role music expert on international economic Iran, as well as her recovery in and video can play in development. -

A Prisoner of Tehran Looks Forward a Prisoner Of

Spring 2013 | Volume 23 | Number 2 Religion Inside this issue Yuengert But What if They’re All Republicans? • Deavel Sentimental Hearts and Invisible Hands • Gregg A Catholic Revolutionary • Liberty Liberal Tradition Margaret Thatcher • Sirico & Creative Destruction A Prisoner of Tehran Looks Forward An Interview with Marina Nemat A Journal of Religion, Economics, and Culture Editor’s Note turmoil and change we are seeing in the Declaration of Independence. the Middle East. The “In the Liberal Tradition” figure is Andrew Yuengert offers the feature Margaret Thatcher (1925 – 2013). piece “But What if They’re All Repub- Thatcher is one of the leading conser- licans?” He argues that a politicized vative political figures of the 20th Catholic episcopacy damages the century. Acton awarded Thatcher the Catholic Church’s social witness. “The Faith & Freedom Award in 2011. She question at issue here is not whether I was interviewed by R&L in 1992. agree with the political stands of the I don’t normally mention “Double- Bishops (I sometimes agree with, and Edged Sword” in the editor’s notes, sometimes reject, their specific policy For many Americans, the iconic images but at a time where many would proposals), but whether they should of the Islamic Revolution in Iran in agree that there is a level of spiritual be acting on behalf of the Church in 1979 are forever etched in the mind. erosion in the West, I felt it appropri- these specific ways,” says Yuengert. The hostage crisis where 52 Ameri- ate. The Scripture selected from Ephe- cans were held in captivity for 444 David Paul Deavel reviews a new sians (3:7-11) might be one of the days in Iran dominated American book by James Otteson on Adam most beautiful passages ever written media and politics. -

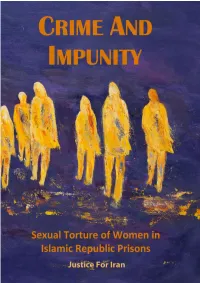

Crime and Impunity

CRIME AND IMPUNITY Sexual Torture of Women in Islamic Republic Prisons Part 1: 1980s Crime and Impunity Sexual Torture of Women in Islamic Republic Prisons Part 1: 1980s First Edition Copyright © Justice For Iran 2012 All rights reserved. Part of this book may be quoted or used as long as the authors and publisher are acknowledged. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted for commercial purposes without prior written permis- sion from the copyright owner. Published by: Justice For Iran [email protected] www.justiceforiran.org Page layout: Aida Book - Germany By Shadi Sadr and Shadi Amin Justice For Iran ISBN 978-3-944191-90-4 About Justice For Iran (JFI) ‘Justice For Iran’ was established in July 2010 with the aim of addressing the crime and impunity prevalent among Iranian state officials and their use of systematic sexual abuse of women as a method of torture in order to extract confession. JFI uses methods such as documentation of human rights violations, col- lecting information, and research about authority figures who play a role in serious and widespread violation of human rights in Iran; as well as use of judicial, political and international mechanisms in place, to execute justice, remove impunity and bring about accountability to the actors and agents of human rights violations in the Islamic Republic of Iran. About the Authors Shadi Sadr is the director of Justice For Iran. She is an Iranian lawyer, human rights defender and journalist. She received her law degree and later her LLM in international law form Tehran University. -

Dear Publisher of Pen

Date: July 25th, 2007 To : Penguin Group ( Canada ) 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700 Toronto , Ontario M4P 2Y3 Phone: 416-925-2249 Fax: 416-925-0068 Email: [email protected] Dear Editorial, Please find enclosed the letter of a group of former political prisoners regarding the book “ Prisoner of Tehran “ written by Marina Nemat. Monireh Baradaran Mainblick 18 61476 Kronberg Germany E-Mail: [email protected] Tel. 0049-6173-998650 Golroch Jahangiri E-Mail: [email protected] Tel. 0049-30- 8535450 Cc: Marina Nemat ( via publisher) Amnesty International University of Toronto Weltbild Buchverlag / Germany Hodder Headline Book Point Voice of America BBC World News Iranian.com The letter of a group of former and tortured political prisoners to Penguin Publications PROTEST AGAINST THE PUBLICATION OF THE PRISONER OF TEHRAN In April 2007 The Prisoner of Tehran was published by Penguin Publications in English. The writer of the book, Marina Nemat, claims that The Prisoner of Tehran is her memoir of her two years and two months imprisonment in Evin Prison in Tehran. For us who have spent many dark years in the in prison, the publication of any book that would shed light on the unknown facts of the prisons of the Islamic Republic, particularly during the 1980’s, is a source of hope. Some of us the signatories of this letter, have published their memories and what they witnessed of their time in prison, some of which have been translated from Farsi into different languages. Unfortunately we have to say that the publication of Ms. Nemat’s book outraged us.