Pasolini, 'Porcile' and the Politics of Consumption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habemus Papam

Fandango Portobello presents a Sacher Films, Fandango and le Pacte production in collaboration with Rai and France 3 Cinema HABEMUS PAPAM a film by Nanni Moretti Running Time: 104 minutes International Fandango Portobello sales: London office +44 20 7605 1396 [email protected] !"!1!"! ! SHORT SYNOPSIS The newly elected Pope suffers a panic attack just as he is due to appear on St Peter’s balcony to greet the faithful, who have been patiently awaiting the conclave’s decision. His advisors, unable to convince him he is the right man for the job, seek help from a renowned psychoanalyst (and atheist). But his fear of the responsibility suddenly thrust upon him is one that he must face on his own. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !"!2!"! CAST THE POPE MICHEL PICCOLI SPOKESPERSON JERZY STUHR CARDINAL GREGORI RENATO SCARPA CARDINAL BOLLATI FRANCO GRAZIOSI CARDINAL PESCARDONA CAMILLO MILLI CARDINAL CEVASCO ROBERTO NOBILE CARDINAL BRUMMER ULRICH VON DOBSCHÜTZ SWISS GUARD GIANLUCA GOBBI MALE PSYCHOTHERAPIST NANNI MORETTI FEMALE PSYCHOTHERAPIST MARGHERITA BUY CHILDREN CAMILLA RIDOLFI LEONARDO DELLA BIANCA THEATER COMPANY DARIO CANTARELLI MANUELA MANDRACCHIA ROSSANA MORTARA TECO CELIO ROBERTO DE FRANCESCO CHIARA CAUSA MASTER OF CEREMONIES MARIO SANTELLA CHIEF OF POLICE TONY LAUDADIO JOURNALIST ENRICO IANNIELLO A MOTHER CECILIA DAZZI SHOP ASSISTANT LUCIA MASCINO TV JOURNALIST MAURIZIO MANNONI HALL PORTER GIOVANNI LUDENO GIRL AT THE BAR GIULIA GIORDANO BARTENDER FRANCESCO BRANDI BOY AT THE BUS LEONARDO MADDALENA PRIEST SALVATORE MISCIO DOCTOR SALVATORE -

MA RCD FERUIP1, F'f Gt'a" PÌ-120 CA, Ccir(I) 1);?-10.(Ja)E{,0 T)E- I

Ferrario, Davide 624 625 Ferreri, Marco ce off rivelando la sua verginità. Deve in- Bibliografia: Davide Ferrario, in Sopralluoghi e Doni- gnala uno dal terrompere gli studi per fare il servizio civi- meritai-i, Torino Film Festival, 1998; Lorenzo Pelliz, Processo di Kafka, cui pensa già nel cita della regolarizzazione dei rapporti: già le, buona occasione per lasciare la famiglia. zar!, Davide Ferrario, Frammenti aguzzi di un discorso 1959, e che costituisce una sugge- El pisito rivela l'intrigante legame fra pro- amoroso, in '>Cineforum»,2000, n. 391. stione di fondo presente in L'udienza. Pur con qualche concessione allo stile da vi- prietà e relazione coniugale, in La donna Quella di Marco Ferreri è una figura atipi- deoclip, il film funziona grazie all'ottimo scimmia questa diventa addirittura il crisma ca nel panorama del cinema italiano, per gli montaggio, all'inventiva della regia e all'in- che permette il cinico sfruttamento della Ferreri, Marco umori che nutrono i suoi film, per le in- terprete, Valerio Mastandrea, talento comi- donna. La storia di L'ape regina - (Milano, 1928 - Parigi, 1997). Studi regola-. un mari- fluenze, per lo stile fatto di accostamenti to progressivamente s'avvia alla morte per co naturale. Fiume di parole, musica e im- ri a Milano, s'iscrive, senza raggiungere la stranianti e di commistioni insolite. Già i adempiere all'«obbligo coniugale» - mette magini, Tutti giú per terra diverte senza vol- laurea, alla facoltà di Veterinaria. L'inte- primi tre film, girati in Spagna (un contesto in luce il dirottamento dell'istinto sessuale garità né cali di ritmo. -

Hiol 20 11 Fraser.Pdf (340.4Kb Application/Pdf)

u 11 Urban Difference “on the Move”: Disabling Mobil- ity in the Spanish Film El cochecito (Marco Ferreri, 1960) Benjamin Fraser Introduction Pulling from both disability studies and mobility studies specifically, this ar- ticle offers an interdisciplinary analysis of a cult classic of Spanish cinema. Marco Ferreri’s filmEl cochecito (1960)—based on a novel by Rafael Azcona and still very much an underappreciated film in scholarly circles—depicts the travels of a group of motorized-wheelchair owners throughout urban (and rural) Madrid. From a disability studies perspective, the film’s focus on Don Anselmo, an able-bodied but elderly protagonist who wishes to travel as his paraplegic friend, Don Lucas, does, suggests some familiar tropes that can be explored in light of work by disability theorists.1 From an (urbanized) mobil- ity studies approach, the characters’ movements through the Spanish capital suggest the familiar image of a filmic Madrid of the late dictatorship, a city that was very much culturally and physically “on the move.”2 Though not un- problematic in its nuanced portrayal of the relationships between able-bodied and disabled Madrilenians, El cochecito nonetheless broaches some implicit questions regarding who has a right to the city and also how that right may be exercised (Fraser, “Disability Art”; Lefebvre; Sulmasy). The significance of Ferreri’s film ultimately turns on its ability to “universalize” disability and connect it to the contemporary urban experience in Spain. What makes El cochecito such a complex film—and such a compelling one—is how a nuanced view of (dis)ability is woven together with explicit narratives of urban modernity and implicit narratives of national progress. -

Conto Alla Rovescia Di Un FESTIVAL

ESPERIENZE FRANCESCANE Conto alla rovescia di un FESTIVAL Si mette a fuoco il programma della manifestazione di settembre di Chiara Vecchio Nepita giornalista, responsabile comunicazione Festival Francescano Appuntamento da non perdere Si avvicina un appuntamento atteso da tutti coloro che ispirano la propria vita alla figura di San Francesco, ne condividono i valori o anche solo ne sono incuriositi. Alla fine dell’estate, precisamente il 25, 26 e 27 settembre, si terrà a Reggio Emilia il primo Festival Francescano, pensato dai cappuccini dell’Emilia-Romagna per festeggiare gli ottocento anni della nascita della Regola francescana. Il programma del Festival, che prevede molte attività anche per i bambini e i ragazzi, si divide in quattro principali tipologie di iniziative: lezioni magistrali, spettacoli, mostre e cinema. Le lezioni magistrali hanno il compito di illustrare, da punti di vista differenti, le questioni legate al francescanesimo. Oltre a Giovanni Salonia, direttore dell’Istituto di Gestalt e a Chiara Frugoni, docente di Storia medievale all’Università di Roma II e Pisa, i cui contributi sono stati anticipati nello scorso numero della rivista, parteciperanno: Stefano Zamagni, docente di Economia presso l’Università degli Studi di Bologna; Lucio Saggioro, docente di Teologia della Comunicazione presso lo Studio Teologico di Venezia; Orlando Todisco, docente di Storia della Filosofia medievale presso l’Università di Cassino e al Seraphicum di Roma; Fulvio De Giorgi, docente di Storia della Pedagogia presso l’Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia; Giorgio Zanetti, docente di Letteratura italiana presso l’Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia. Il mondo del giornalismo è rappresentato da Gabriella Caramore, collaboratrice dagli inizi degli anni Ottanta di Rai Radio Tre (sua la conduzione della trasmissione “Uomini e Profeti”) e autrice de “La fatica della luce”, un libro di domande sul religioso. -

Uw Cinematheque Announces Fall 2012 Screening Calendar

CINEMATHEQUE PRESS RELEASE -- FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AUGUST 16, 2012 UW CINEMATHEQUE ANNOUNCES FALL 2012 SCREENING CALENDAR PACKED LINEUP INCLUDES ANTI-WESTERNS, ITALIAN CLASSICS, PRESTON STURGES SCREENPLAYS, FILMS DIRECTED BY ALEXSEI GUERMAN, KENJI MISUMI, & CHARLES CHAPLIN AND MORE Hot on the heels of our enormously popular summer offerings, the UW Cinematheque is back with the most jam-packed season of screenings ever offered for the fall. Director and cinephile Peter Bogdanovich (who almost made an early version of Lonesome Dove during the era of the revisionist Western) writes that “There are no ‘old’ movies—only movies you have already seen and ones you haven't.” With all that in mind, our Fall 2012 selections presented at 4070 Vilas Hall, the Chazen Museum of Art, and the Marquee Theater at Union South offer a moveable feast of outstanding international movies from the silent era to the present, some you may have seen and some you probably haven’t. Retrospective series include five classic “Anti-Westerns” from the late 1960s and early 70s; the complete features of Russian master Aleksei Guerman; action epics and contemplative dramas from Japanese filmmaker Kenji Misumi; a breathtaking survey of Italian Masterworks from the neorealist era to the early 1970s; Depression Era comedies and dramas with scripts by the renowned Preston Sturges; and three silent comedy classics directed by and starring Charles Chaplin. Other Special Presentations include a screening of Yasujiro Ozu’s Dragnet Girl with live piano accompaniment and an in-person visit from veteran film and television director Tim Hunter, who will present one of his favorite films, Tsui Hark’s Shanghai Blues and a screening of his own acclaimed youth film, River’s Edge. -

Naples and the Nation in Cultural Representations of the Allied Occupation. California Italian Studies, 7(2)

Glynn, R. (2017). Naples and the Nation in Cultural Representations of the Allied Occupation. California Italian Studies, 7(2). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vp8t8dz Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY-NC Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via University of California at https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vp8t8dz . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ UC Berkeley California Italian Studies Title Naples and the Nation in Cultural Representations of the Allied Occupation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vp8t8dz Journal California Italian Studies, 7(2) Author Glynn, Ruth Publication Date 2017-01-01 License CC BY-NC 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Naples and the Nation in Cultural Representations of the Allied Occupation Ruth Glynn The Allied Occupation in 1943–45 represents a key moment in the history of Naples and its relationship with the outside world. The arrival of the American Fifth Army on October 1, 1943 represented the military liberation of the city from both Nazi fascism and starvation, and inaugurated an extraordinary socio-cultural encounter between the international troops of the Allied forces and a war-weary population. -

Note Nel Frastuono Del Presente: Pasolini, Manganelli, Landolfi, Pavese

SEBASTIANO TRIULZI Note nel frastuono del presente: Pasolini, Manganelli, Landolfi, Pavese Diacritica Edizioni 2018 «Ofelia», 4 SEBASTIANO TRIULZI Note nel frastuono del presente: Pasolini, Manganelli, Landolfi, Pavese Diacritica Edizioni 2018 Copyright © 2018 Diacritica Edizioni di Anna Oppido Via Tembien 15 – 00199 Roma www.diacriticaedizioni.it www.diacriticaedizioni.com [email protected] Iscrizione al Registro Operatori Comunicazione n. 31256 ISBN 978-88-31913-058 Pubblicato nel mese di marzo 2018 Quest’opera è diffusa in modalità open access. Realizzazione editoriale e revisione del testo a cura di Maria Panetta. Indice Prefazione Il frastuono del Novecento e la Poesia, di Maria Panetta……….…...……… p. 9 Breve nota al testo…………………………………..……………..……….. p. 11 Sul set di Medea. Pier Paolo Pasolini e Maria Callas………..…………….. p. 13 Il corpo di Pasolini. Considerazioni intorno a un’esposizione……..….…… p. 23 Curiosando fra le tesi degli scrittori nell’Archivio dell’Università di Torino…………………………………………………………..…………… p. 45 Una letteratura di parole, non di cose. Breve nota su Cesare Pavese…...…. p. 73 Versi virali e follower: ingrate illusioni degli Instapoeti………...………….. p. 81 Crollo, avidità e salute: la malattia del denaro in Pirandello Gadda e Svevo. Per una storia economica della letteratura……………………………………....…. p. 93 Ansie sublunari e avvistamenti di UFO negli scritti giornalistici di Giorgio Manganelli…………………………………………………………………….…… p. 113 Isotopie «famigliari» nel Racconto d’autunno di Tommaso Landolfi…....… p. 135 Attilio Bertolucci 1925-1929: nascita e avvento di Sirio……………..….….. p. 165 7 Prefazione Il frastuono del Novecento e la Poesia Dedicato all’Italia è questo terzo volume di Triulzi, che segue, nella collana intitolata a «Ofelia», ad altri due libri rispettivamente incentrati su alcune voci femminili e sulla letteratura di grandi interpreti della realtà contemporanea in forma di narrazione. -

Company Profile Fenix Entertainment About Us

COMPANY PROFILE FENIX ENTERTAINMENT ABOUT US Fenix Entertainment is a production company active also in the music industry, listed on the stock exchange since August 2020, best newcomer in Italy in the AIM-PRO segment of the AIM ITALIA price list managed by Borsa Italiana Spa. Its original, personalized and cutting-edge approach are its defining features. The company was founded towards the end of 2016 by entrepreneurs Riccardo di Pasquale, a former bank and asset manager and Matteo Di Pasquale formerly specializing in HR management and organization in collaboration with prominent film and television actress Roberta Giarrusso. A COMBINATION OF MANY SKILLS AT THE SERVICE OF ONE PASSION. MILESTONE 3 Listed on the stock exchange since 14 Produces the soundtrack of Ferzan Produces the film ‘’Burraco Fatale‘’. August 2020, best newcomer in Italy in Ozpetek's “Napoli Velata” the AIM-PRO segment of the AIM ITALIA price list managed by Borsa Italiana Spa First co-productions Produces the soundtrack "A Fenix Entertainment cinematographic mano disarmata" by Claudio Distribution is born Bonivento Acquisitions of the former Produces the television Produces the film works in the library series 'That’s Amore' “Ostaggi” Costitution Fenix Attend the Cannes Film Festival Co-produces the film ‘’Up & Produces the “DNA” International and the International Venice Film Down – Un Film Normale‘’ film ‘Dietro la product acquisition Festival notte‘’ 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 “LA LUCIDA FOLLIA DI MARCO FERRERI” “UP&DOWN. UN FILM “NAPOLI VELATA” original “BEST REVELATION” for Fenix Entertainment • David di Donatello for Best Documentary NORMALE” Kineo award soundtrack Pasquale Catalano Anna Magnani Award to the production team • Nastro d’Argento for Best Film about Cinema for Best Social Docu-Film nominated: • David di Donatello for Best Musician • Best Soundtrack Nastri D’Argento “STIAMO TUTTI BENE” by Mirkoeilcane “DIVA!” Nastro D’Argento for the Best “UP&DOWN. -

Morneault Thesis

A Barthesean Analysis of Revisionist Stagings of Verdi's La Traviata Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Morneault, Gwyndolyn E. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 23:11:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/636931 A BARTHESEAN ANALYSIS OF REVISIONIST STAGINGS OF VERDI’S LA TRAVIATA by Gwyndolyn Morneault ____________________________ Copyright © Gwyndolyn Morneault 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC WITH A MAJOR IN MUSICOLOGY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 3 Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 CHAPTER I: REVISIONIST DIRECTORS ............................................................................................................ 6 Revising La Traviata ................................................................................................................................................ -

Sunday Morning Grid 6/26/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

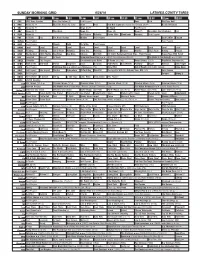

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/26/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Paid Red Bull Signature Series From Detroit. (N) Å Beach Volleyball 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Incredible Dog Challenge Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Earth 2050 FabLab 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Happy Yoga With Sarah 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. (PG-13) The World Is Not Enough ›› (1999) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Un recuerdo para Rubé Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Firehouse Dog ›› (2007) Josh Hutcherson. -

Extinction of a Minor Species Im Bockenheimer Depot

477-18-06 s Juni 2018 www.strandgut.de für Frankfurt und Rhein-Main D A S K U L T U R M A G A Z I N >> Film Die brilliante Mademoiselle Neïla von Yvan Attal ab 14. Juni >> Special 70 Jahre Luftbrücke Frankfurt-Berlin Gail Halvorsen kommt ins Orfeos Erben >> Tanz Extinction of a Minor Species im Bockenheimer Depot >> Theater Bonjour Tristesse im Kellertheater >> Kunst O Sentimental Machine im Liebieghaus >> Musik Brian Fallon am 10. Juni im Schlachthof Wiesbaden NEUFASSUNG EXTINCTION OF A MINOR SPECIES 2018 8. 10., 13. 16. juni 20Uhr Tickets BOCKENHEIMER DEPOT 069 212 494 94 FRANKFURT AM MAIN dresdenfrankfurtdancecompany.de INHALT Film 4 Die brillante Mademoiselle Neïla von Yvan Atal 5 Kolyma von Stanislaw Mucha 6 Swimming with Men von Oliver Parker 7 abgedreht Tully 8 Der Blick zurück 70 Jahre Luftbrücke Ffm.-Berlin 9 Filmstarts Theater 15 Tanztheater 17 The Invisible Hand im English Theatre Immer das richtige 18 vorgeführt Argument zur Hand Marina Vlady © DIF 18 Woyzeck im Schauspiel Frankfurt »Die brillante Mademoiselle Neïla« 19 Bonjour Tristesse von Yvan Atal im Kellertheater Der Jura-Professor Pierre Ma- 20 Stimmen einer Stadt im Schauspiel Frankfurt 4 zard ist zweifellos ein gebildeter 21 Claube Liebe Hoffnung Mann. Doch ihm fehlt, was man ro- im Staatstheater Darmstadt mantisch Herzensbildung oder et- 22 Dinge, die ich sicher weiß & Die Nibelungen was einfacher Mitgefühl nennt. Weil im Staatstheater Mainz er zusätzlich noch zu sehr von sich Am Strand 23 Premieren überzeugt ist, unterbricht er seine 24 Die Möwe & Nora Vorlesung und redet sich in Rage, als im Staatstheater Wiesbaden 25 Neue Produktionen eine Erstsemester-Studentin zu spät 26 Musiktheater kommt. -

MARCO FERRERI the Director Who Came from the Future

MASSIMO VIGLIAR presents a production SURF FILM – ORME – LA7 MARCO FERRERI The director who came from the future a documentary film by MARIO CANALE With the participation of: Rafael Azcona, Nicoletta Braschi, Franco Brocani, Jerry Calà, Sergio Castellitto, Pappi Corsicato, Piera Degli Esposti, Francesca Dellera, Maruschka Detmers, Nicoletta Ercole, Sabrina Ferilli, Andréa Ferréol, Enzo Jannacci, Christopher Lambert, Citto Maselli, Gianni Massaro, Ornella Muti, Philippe Noiret, Esteve Riambau, Ettore Rosboch, Dado Ruspoli, Alfonso Sansone, Giancarlo Santi, Philippe Sarde, Catherine Spaak, Lina Nerli Taviani, Ricky Tognazzi, Mario Vulpiani narrator: Michele Placido Music: Philippe Sarde Non contractual credits TECHNICAL DATA Marco Ferreri, the director who came from the future ITALIA 2007, b/w and colour, 90’ Direction: Mario Canale Story and screenplay: Mario Canale, Annarosa Morri Narrator: Michele Placido Music: Philippe Sarde Editing: Adalberto Gianuario, Alessandro Raso Photography: Maurizio Carta, Massimo Coconi, Paolo Mancini, Marcello Rapezzi, Mario Canale Iconography research: Rosellina d’Errico Executive production: Mario Canale, Elena Francot Archive images: Orme Istituto Luce Aamod – Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Fondazione Mario Schifano TVE – A fondo - 1978 Argento puro di Pappi Corsicato Giancarlo Santi : facevo er Cinema di Anton Giulio Mancino Italia Taglia di Tatti Sanguineti Antonioni di Gianfranco Mingozzi Period pictures : Jacqueline Ferreri Reporters Associati Images of the film for kind concession of: Jacqueline Ferreri Surf film: Controsesso, La donna scimmia, La Carne, Diario di un vizio, L’uomo dei 5 palloni, Casanova 70, Il fischio al naso, Cronaca di un amore. Myra Film : La Grande abbuffata, Non toccare la donna bianca, Ciao Maschio, Il seme dell’uomo, El Cochecito, La casa del sorriso, Nitrato d’argento.