Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Semaphore Circular No 659 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016

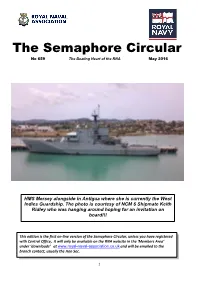

The Semaphore Circular No 659 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016 HMS Mersey alongside in Antigua where she is currently the West Indies Guardship. The photo is courtesy of NCM 6 Shipmate Keith Ridley who was hanging around hoping for an invitation on board!!! This edition is the first on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. April Open Day 2. New Insurance Credits 3. Blonde Joke 4. Service Deferred Pensions 5. Guess Where? 6. Donations 7. HMS Raleigh Open Day 8. Finance Corner 9. RN VC Series – T/Lt Thomas Wilkinson 10. Golf Joke 11. Book Review 12. Operation Neptune – Book Review 13. Aussie Trucker and Emu Joke 14. Legion D’Honneur 15. Covenant Fund 16. Coleman/Ansvar Insurance 17. RNPLS and Yard M/Sweepers 18. Ton Class Association Film 19. What’s the difference Joke 20. Naval Interest Groups Escorted Tours 21. RNRMC Donation 22. B of J - Paterdale 23. Smallie Joke 24. Supporting Seafarers Day Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General -

The British Commonwealth and Allied Naval Forces' Operation with the Anti

THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH AND ALLIED NAVAL FORCES’ OPERATION WITH THE ANTI-COMMUNIST GUERRILLAS IN THE KOREAN WAR: WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE OPERATION ON THE WEST COAST By INSEUNG KIM A dissertation submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the British Commonwealth and Allied Naval forces operation on the west coast during the final two and a half years of the Korean War, particularly focused on their co- operation with the anti-Communist guerrillas. The purpose of this study is to present a more realistic picture of the United Nations (UN) naval forces operation in the west, which has been largely neglected, by analysing their activities in relation to the large number of irregular forces. This thesis shows that, even though it was often difficult and frustrating, working with the irregular groups was both strategically and operationally essential to the conduct of the war, and this naval-guerrilla relationship was of major importance during the latter part of the naval campaign. -

Security & Defence European

a 7.90 D European & Security ES & Defence 4/2016 International Security and Defence Journal Protected Logistic Vehicles ISSN 1617-7983 • www.euro-sd.com • Naval Propulsion South Africa‘s Defence Exports Navies and shipbuilders are shifting to hybrid The South African defence industry has a remarkable breadth of capa- and integrated electric concepts. bilities and an even more remarkable depth in certain technologies. August 2016 Jamie Shea: NATO‘s Warsaw Summit Politics · Armed Forces · Procurement · Technology The backbone of every strong troop. Mercedes-Benz Defence Vehicles. When your mission is clear. When there’s no road for miles around. And when you need to give all you’ve got, your equipment needs to be the best. At times like these, we’re right by your side. Mercedes-Benz Defence Vehicles: armoured, highly capable off-road and logistics vehicles with payloads ranging from 0.5 to 110 t. Mobilising safety and efficiency: www.mercedes-benz.com/defence-vehicles Editorial EU Put to the Test What had long been regarded as inconceiv- The second main argument of the Brexit able became a reality on the morning of 23 campaigners was less about a “democratic June 2016. The British voted to leave the sense of citizenship” than of material self- European Union. The majority that voted for interest. Despite all the exception rulings "Brexit", at just over 52 percent, was slim, granted, the United Kingdom is among and a great deal smaller than the 67 percent the net contribution payers in the EU. This who voted to stay in the then EEC in 1975, money, it was suggested, could be put to but ignoring the majority vote is impossible. -

Japan Im Ersten Weltkrieg

ÖSTERREICHISCHEÖMZ MILITÄRISCHE ZEITSCHRIFT In dieser Onlineausgabe Harald Pöcher Japan im Ersten Weltkrieg Nikolaus Scholik Power-Projection vs Anti-Access/Area-Denial (A2/AD) Die operationellen Konzepte von U.S. Navy (USN) und Peoples Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) im Indo-Pazifischen Raum Andreas Armborst Dschihadismus im Irak Andreas Steiger Die Berufsoffiziersausbildung an der Theresianischen Militärakademie in Wr. Neustadt Beiträge zur Geschichte des Bundesheeres der 1. Republik von 1934-1938 Zusätzlich in der Printausgabe Walter Schilling Die Problematik der pazifistischen Grundströmung in Deutschland Hans Krech Die direkte Einflussnahme der strategischen Führungsebene von Al Qaida auf interne Konflikte in den Regionalorganisationen Heino Matzken Zwist statt Liebe in der Geburtskirche Ewiger christlicher Zankapfel auch Spielball im palästinensisch-israelischen Staatspoker! Klaus-Jürgen Bremm Die elektrische Telegraphie als Mittel militärischer Führung und der Nachrichtengewinnung in den deutschen Einigungskriegen sowie zahlreiche Berichte zur österreichischen und internationalen Verteidigungspolitik ÖMZ 4/2014-Online ÖMZ itärisc Mil he Z e ei h ts sc c i h h r Japan im Ersten Weltkrieg c i i f e t r r e t s Ö w Peer Revie Harald Pöcher 1808 er japanische Beitrag zum Ersten Weltkrieg Nation-starke Armee). Unmittelbar nach der Öffnung des führte zu einer Neugestaltung des westpazi- Landes gaben sich die ausländischen Militärdelegationen - Dfisch-ostasiatischen Raumes und schuf damit auch in der Hoffnung auf gute Geschäfte für ihre Rüstungs- -

Master Narrative Ours Is the Epic Story of the Royal Navy, Its Impact on Britain and the World from Its Origins in 625 A.D

NMRN Master Narrative Ours is the epic story of the Royal Navy, its impact on Britain and the world from its origins in 625 A.D. to the present day. We will tell this emotionally-coloured and nuanced story, one of triumph and achievement as well as failure and muddle, through four key themes:- People. We tell the story of the Royal Navy’s people. We examine the qualities that distinguish people serving at sea: courage, loyalty and sacrifice but also incidents of ignorance, cruelty and cowardice. We trace the changes from the amateur ‘soldiers at sea’, through the professionalization of officers and then ships’ companies, onto the ‘citizen sailors’ who fought the World Wars and finally to today’s small, elite force of men and women. We highlight the change as people are rewarded in war with personal profit and prize money but then dispensed with in peace, to the different kind of recognition given to salaried public servants. Increasingly the people’s story becomes one of highly trained specialists, often serving in branches with strong corporate identities: the Royal Marines, the Submarine Service and the Fleet Air Arm. We will examine these identities and the Royal Navy’s unique camaraderie, characterised by simultaneous loyalties to ship, trade, branch, service and comrades. Purpose. We tell the story of the Royal Navy’s roles in the past, and explain its purpose today. Using examples of what the service did and continues to do, we show how for centuries it was the pre-eminent agent of first the British Crown and then of state policy throughout the world. -

Military Operations in Libya

Military Operations in Libya Standard Note: SN/IA/5909 Last updated: 24 October 2011 Author: Claire Taylor Section International Affairs and Defence Section On 17 March 2011 the UN Security Council adopted resolution 1973 (2011), under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, which authorised the use of force, including enforcement of a no-fly zone, enforcement of a UN arms embargo against Libya and to protect civilians and civilian areas targeted by the Qaddafi regime and its supporters. The weekend of 19/20 March saw French, British and US military action begin under Operation Odyssey Dawn. By the end of March command of that operation had been gradually transitioned to NATO. On 23 March NATO assumed command of operations to enforce the UN arms embargo. The transfer of command responsibility for the no-fly zone was agreed on 24 March; while the decision to transfer command and control for all military operations in Libya was taken on 27 March. NATO formally assumed command under Operation Unified Protector at 0600 hours on 31 March 2011. Military operations have been ongoing for seven months. During that time there have been criticisms of stalemate in the military campaign, allegations over burden sharing among NATO Member States, and questions over the existence of a viable exit strategy. Following the fall of Sirte and the death of Colonel Gadaffi, Libya’s transitional government declared liberation on 23 October 2011. The NATO Secretary General also confirmed in a statement that a preliminary decision had been taken to end Operation Unified Protector on 31 October 2011. However, he also went on to state that NATO would monitor the situation and retain the capacity to respond to threats to civilians if necessary. -

Thank You, Father Kim Il Sung” Is the First Phrase North Korean Parents Are Instructed to Teach to Their Children

“THANK YOU FATHER KIM ILLL SUNG”:”:”: Eyewitness Accounts of Severe Violations of Freedom of Thought, Conscience, and Religion in North Korea PPPREPARED BYYY: DAVID HAWK Cover Photo by CNN NOVEMBER 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Michael Cromartie Chair Felice D. Gaer Vice Chair Nina Shea Vice Chair Preeta D. Bansal Archbishop Charles J. Chaput Khaled Abou El Fadl Dr. Richard D. Land Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou Bishop Ricardo Ramirez Ambassador John V. Hanford, III, ex officio Joseph R. Crapa Executive Diretor NORTH KOREA STUDY TEAM David Hawk Author and Lead Researcher Jae Chun Won Research Manager Byoung Lo (Philo) Kim Research Advisor United States Commission on International Religious Freedom Staff Tad Stahnke, Deputy Director for Policy David Dettoni, Deputy Director for Outreach Anne Johnson, Director of Communications Christy Klaasen, Director of Government Affairs Carmelita Hines, Director of Administration Patricia Carley, Associate Director for Policy Mark Hetfield, Director, International Refugee Issues Eileen Sullivan, Deputy Director for Communications Dwight Bashir, Senior Policy Analyst Robert C. Blitt, Legal Policy Analyst Catherine Cosman, Senior Policy Analyst Deborah DuCre, Receptionist Scott Flipse, Senior Policy Analyst Mindy Larmore, Policy Analyst Jacquelin Mitchell, Executive Assistant Tina Ramirez, Research Assistant Allison Salyer, Government Affairs Assistant Stephen R. Snow, Senior Policy Analyst Acknowledgements The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom expresses its deep gratitude to the former North Koreans now residing in South Korea who took the time to relay to the Commission their perspectives on the situation in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and their experiences in North Korea prior to fleeing to China. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. Donald Macintyre, Narvik (London: Evans, 1959), p. 15. 2. See Olav Riste, The Neutral Ally: Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War (London: Allen and Unwin, 1965). 3. Reflections of the C-in-C Navy on the Outbreak of War, 3 September 1939, The Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs, 1939–45 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 37–38. 4. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 10 October 1939, in ibid. p. 47. 5. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 8 December 1939, Minutes of a Conference with Herr Hauglin and Herr Quisling on 11 December 1939 and Report of the C-in-C Navy, 12 December 1939 in ibid. pp. 63–67. 6. MGFA, Nichols Bohemia, n 172/14, H. W. Schmidt to Admiral Bohemia, 31 January 1955 cited by Francois Kersaudy, Norway, 1940 (London: Arrow, 1990), p. 42. 7. See Andrew Lambert, ‘Seapower 1939–40: Churchill and the Strategic Origins of the Battle of the Atlantic, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), pp. 86–108. 8. For the importance of Swedish iron ore see Thomas Munch-Petersen, The Strategy of Phoney War (Stockholm: Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1981). 9. Churchill, The Second World War, I, p. 463. 10. See Richard Wiggan, Hunt the Altmark (London: Hale, 1982). 11. TMI, Tome XV, Déposition de l’amiral Raeder, 17 May 1946 cited by Kersaudy, p. 44. 12. Kersaudy, p. 81. 13. Johannes Andenæs, Olav Riste and Magne Skodvin, Norway and the Second World War (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1966), p. -

The Royal Canadian Navy and Operation Torch, 1942-19431

"A USEFUL LOT, THESE CANADIAN SHIPS:" THE ROYAL CANADIAN NAVY AND OPERATION TORCH, 1942-19431 Shawn Cafferky Like other amphibious animals we must come occasionally on shore: but the water is more properly our element, and in it...as we find our greatest security, so exert our greatest force. Bolingbroke, Idea of a Patriot King (1749) The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) corvettes that supported the Allied landings in North Africa beginning in November 1942 achieved substantial success. This little-known story is important, for the Canadian warships gave outstanding service at a time when the fortunes of the main RCN escort forces in the north Atlantic had dropped to their nadir. Problems resulting from overexpansion and overcommitment had, as has been fully documented in recent literature, raised grave doubts about the efficiency of Canadian escorts.2 What has yet to be properly acknowledged was that the operations of RCN ships in the Mediterranean and adjacent eastern Atlantic areas during these same months of crisis demonstrated that given an opportunity Canadian escorts could match the best. On 25 July 1942, after months of high-level discussions concerning the strategic direction of the war, Allied leaders agreed to invade North Africa in a campaign named Operation Torch, rather than immediately opening a second front in Europe. On 27 August 1942 the First Sea Lord signalled Vice-Admiral P.W. Nelles, Chief of the Naval Staff (CNS), "that Admiral Cunningham's [Naval Commander Expeditionary Force] Chief of Staff, Commodore R.M. Dick, would be visiting him in Ottawa with some information."3 The material proved to be an outline of Operation Torch, along with a request that the RCN provide escorts for the operation. -

Lead and Line September

september 2015 volume 30, issue No. 7 LEAD AND LINE newsletter of the naval Association of vancouver island A Royal Toast Haida in drydock Russia’s Messy Naval Day Life of Richard Leir Page 3 Page 4 Page 8 Page 9 HMCS Fredericton's CH-124 Sea King helicopter conducting hoists during Operation Reassurance this summer. Photo: Cpl Charles A. Stephen Speaker: LCdr. Martin Head, Executive NAC-VI Officer RCSU Pacific, who will be speaking on 28 Sept the Sea Cadet Program in British Columbia as well as the recent Summer Training for Cadets Luncheon at HMCS Quadra. Guests - spouses, friends, family are most welcome Please contact Kathie Csomany Lunch at the Fireside Grill at 1130 for 1215 [email protected] or 250-477-4175 prior to 4509 West Saanich Road, Royal Oak, Saanich. noon on Thursday 24 Sep. Please advise of any allergies or food sensitivities. NACVI • PO box 5221, Victoria BC • Canada V8R 6N4 • www.noavi.ca • Page 1 september 2015 volume 30, issue No. 7 NAC-VI LEAD AND LINE See below in this publication for a listing of the new Board as well as members that have taken on special appointments. Lo. will also note that President’s a few former positions, Membership and Nro9 grams are still to be Cilled. These are big tasks Message and we, as a Board, will be looking at innovative sol.tions, perhaps breaking .p the load a bit. Sept 2015 If an1 of 1o. have some time, and will be willing to take on some tasks, please contact me and we will gladly include you. -

Hms Sheffield Commission 1975

'During the night the British destroyers appeared once more, coming in close to deliver their torpedoes again and again, but the Bismarck's gunnery was so effective that none of them was able to deliver a hit. But around 08.45 hours a strongly united attack opened, and the last fight of the Bismarck began. Two minutes later, Bismarck replied, and her third volley straddled the Rodney, but this accuracy could not be maintained because of the continual battle against the sea, and, attacked now from three sides, Bismarck's fire was soon to deteriorate. Shortly after the battle commenced a shell hit the combat mast and the fire control post in the foremast broke Gerhard Junack, Lt Cdr (Eng), away. At 09.02 hours, both forward heavy gun turrets were put out of action. Bismarck, writing in Purnell's ' A further hit wrecked the forward control post: the rear control post was History of the Second World War' wrecked soon afterwards... and that was the end of the fighting instruments. For some time the rear turrets fired singly, but by about 10.00 hours all the guns of the Bismarck were silent' SINK the Bismarck' 1 Desperately fighting the U-boat war and was on fire — but she continued to steam to the picture of the Duchess of Kent in a fearful lest the Scharnhorst and the south west. number of places. That picture was left Gneisenau might attempt to break out in its battered condition for the re- from Brest, the Royal Navy had cause for It was imperative that the BISMARCK be mainder of SHEFFIELD'S war service. -

Sunset for the Royal Marines? the Royal Marines and UK Amphibious Capability

House of Commons Defence Committee Sunset for the Royal Marines? The Royal Marines and UK amphibious capability Third Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 30 January 2018 HC 622 Published on 4 February 2018 by authority of the House of Commons The Defence Committee The Defence Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Ministry of Defence and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Dr Julian Lewis MP (Conservative, New Forest East) (Chair) Leo Docherty MP (Conservative, Aldershot) Martin Docherty-Hughes MP (Scottish National Party, West Dunbartonshire) Rt Hon Mark Francois MP (Conservative, Rayleigh and Wickford) Graham P Jones MP (Labour, Hyndburn) Johnny Mercer MP (Conservative, Plymouth, Moor View) Mrs Madeleine Moon MP (Labour, Bridgend) Gavin Robinson MP (Democratic Unionist Party, Belfast East) Ruth Smeeth MP (Labour, Stoke-on-Trent North) Rt Hon John Spellar MP (Labour, Warley) Phil Wilson MP (Labour, Sedgefield) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/defcom and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the inquiry page of the Committee’s website. Committee staff Mark Etherton (Clerk), Dr Adam Evans (Second Clerk), Martin Chong, David Nicholas, Eleanor Scarnell, and Ian Thomson (Committee Specialists), Sarah Williams (Senior Committee Assistant), and Carolyn Bowes and Arvind Gunnoo (Committee Assistants).