Democracy in Action: Communicative Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recreation. Fun. Family. • Excavation of Silver and Copper Ores

231 2 32 4 5 6 Fun and action for the whole family Abenteuerpfad Hausach Aussichtsturm Urenkopf Let your feet roam freely... Blac orest Treeto al Besucherbergwerk Grube Wenzel – Get on top of the black forest! underground treasure The GALAXY SCHWARZWALD is one of the most The adventure trail contains 20 play stations made The „Urenkopfturm“, with its slender form and 183 ...in the „BarfussPark“ in Dornstetten-Hallwangen. modern and largest water slide parks in the whole of from natural materials spread over a length of about steps, extends above the highest point of the „Barefoot over hill and dale“ is the motto each year The „Baumwipfelpfad Schwarzwald“ lets you walk In the „Grube Wenzel“ exhibition mine in Oberwolfach Europe. Young and old guests will have an absolute 2.8 km. The path leads along a small stream, more Haslach mountain, the „Urenkopf“, at a height of 554 from 1 May at the „BarfussPark“ in Dornstetten- at eye level with the treetops. Learning stations you will discover one of the most important silver mines ball on 22 high-tech slides, including the world‘s lar- of a rivulet, but still a gorge for children, which they metres, and provides a magnificent panoramic view Hallwangen. The path leads through a small valley along the 1.2 km-long path on the Sommerberg in in the central Black Forest. gest stainless steel half-pipe, Baden-Württemberg‘s can cross with the help of ropes. A range of balancing across the central Black Forest to the Rhine valley, with a stream and meadows and enters a forest in Bad Wildbad let you have fun while learning about longest rubber-ring slide, a unique wave pool and stations line the path. -

1 Germany on the Eve of Reformation

1 Germany on the Eve of Reformation When the Habsburg Emperor Maximilian I died on 12 January 1519, rumours were rife that ships were moving down the Rhine with sacks of French gold tied to their hulls. Denied bills of exchange by the German bankers, agents of the French monarch were forced to such desperate measures in order to ensure that their king, Francis I, had enough ready wealth at his disposal to contest the pending imperial election. Opposing Francis I was Maximilian’s grandson Charles, Duke of Burgundy and King of Spain, whose agents, while conceding that ‘these devils of Frenchmen scatter gold in all directions,’ had managed to win most of the seven electors over to the Habsburg candidate using similar methods of bribes and benefices (Knecht, 1994, p. 166). Other potentates had come forward, including Henry of England and Friedrich the Wise of Saxony, but ultimately the imperial election crystallized into a contest between the Valois king of France and the Habsburg heir Charles of Ghent. And it was an event of profound importance, for in essence it was a struggle between the two most powerful sovereigns in Europe for rule over one of the largest empires of the age. All of the major European sovereigns followed the election with great interest, including the Medici Pope Leo X, who, fearing the King of Spain more than the King of France, sided with Francis I. But an imperial election was not decided by foreign powers. The electors of the Holy Roman Empire would choose the next king, and in the end Charles was elected unanimously because it was thought that the Habsburg was the best choice for the German 2 Germany on the Eve of Reformation lands.The King of France, it was believed, would not respect the liberties of the Empire, and no internal candidate had enough personal might to command the realm. -

Black Forest

Black Forest Our beautiful landscapes, romantic towns and villages, famous museums and great concerts, traditional spas and highly acclaimed cuisine are The Black Forest among the best reasons to visit the Black Forest. Traditionally hospitable. Visit the home of the convenient access to everything from Bollenhut and the Black adventure to enjoyment and nature Forest to culture. The most frequently visited high- How to get there Black Forest girls, farmhouses, Black lights of the Black Forest are towns By rail: The Black Forest holiday region is Forest cake and ham, the Bollenhut like Baden-Baden and Freiburg, the easy to reach by rail on various ICE, TGV, and the cuckoo clock – known the Triberg waterfall and the world fa- Intercity, EuroCity, and CityNight lines from world over, these traditional features mous Titisee. all over Europe. make for a storybook holiday in one For timetables, tickets etc: www.bahn.de of Europe’s most beautiful destina- Other attractions of the Black Forest tions. include impressively beautiful and By car: Reaching the Black Forest by car is historic towns, the traditional quick and easy: To the west is Autobahn A5/ The natural surroundings shift from half-timbered houses, romantic cas- E35; to the east is A81/E41; to the north A8/ sunny vineyards to shadowy forests. tles and palaces, unique churches E52; to the south A98 and B34. From Zürich, Upland moors and lakes, climbing and monasteries. take the Autobahn 3 toward Basel. On the rocks and orchards, the gentle hills in Invitingly charming French side of the Rhine, A35, E25, and N83 the east and the Kaiserstuhl in the run close to the Black Forest. -

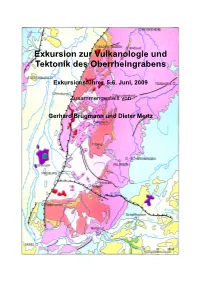

Exkursion Zur Vulkanologie Und Tektonik Des Oberrheingrabens

Exkursion zur Vulkanologie und Tektonik des Oberrheingrabens Exkursionsführer, 5-6. Juni, 2009 Zusammengestellt von Gerhard Brügmann und Dieter Mertz Field Trip Schedule 05. Juni 2009 Geologie des Kaiserstuhl-Vulkankomplexes 07:00 Busabfahrt, vor dem Geo-Institut 9:30 Ankunft Vogelsangpass zwischen Oberschaffhausen und Vogtsburg 1. Vogelsangpass, Einführung Oberrheingraben und Kaiserstuhlüberblick 2. Phonolit bei Endhahlen, SWW von Eichstätten 3. Karbonatit und subvulkanische Brekkzie am Ohrberg, Schelingen 4. Limburgite und Nephelinite am Limberg und Lützelberg, NW Sasbach 5. Essexit-Intrusion und Tephrit-Laven am Fuß von Kastell Sponeck 6. Tehritlaven am Vulkanfelsen, westlich Ihringen 19:00 Uhr Unterkunft Gast zum Löwen in Sasbach - 2 - Field Trip Schedule 06. Juni 2009 Geologie Rheingrabengrand und südlicher Schwarzwald 7:30 Uhr Frühstück 8:00 Uhr Abfahrt Richtung Badenweiler 7. Quarzriff, S Badenweiler, Wanderung Klinik Hausbaden – Alter Mann 8. Schwärzestraße, nördlich Badenweiler, Rheingrabenrandstörung (Muschelkalk/Kulmkonglomerat) 9. Parkplatz Schwärze, Wanderung entlang Geopfad: Lias, Dogger, Tertiär, 10. Weiterfahrt Landstraße L131 Richtung Schönau, Malsburg-Granit 11. Schönau-Geschwend, Randgranit 12. Wanderung Sengalenkopfweg, Randgranit-Sengalenkopfschiefer- 13. Stierhütte / Falkau, Migmatitischer Paragneis der Unit 1 im CSGC 14. Lochütte/Alpesbach, WSW von Hinterzarten; Eklogite der Unit-1 im CSGC Rückfahrt über Kirchzarten - Freiburg – A5 - Mainz - 3 - A. The Upper Rhine Graben and the Kaiserstuhl Volcanic Complex Introduction Two geodynamic events affected the West-European plate during the Cenozoic: (1) the Alpine orogeny, which is related to convergence between the African and European plates, and which started during the Late Cretaceous and is still ongoing; (2) the opening of the European Cenozoic Rift System (ECRIS) that started during the Late Eocene (Fig. 1). -

The Sercret of Hotel Dollenberg

READY FOR A REFRESH The Dollenberg in full bloom this summer! 2021 TARIFFS AND PACKAGES We have made use of recent months to renew the Dollenberg in readiness for a fresh A TIME OF summer start. You can look forward to our exciting new look, including: RENEWAL ... remodelled pool area ... refurbished restaurants ... new gym with state-of-the-art equipment Dear Dollenberg guests and friends, ... overhauled sauna world ... new bathrooms and many rooms Do you share our excitement at the prospect of the sun’s warming rays setting our faces ... brand new junior and luxury suites and hearts aglow? Of the ripe taste of summer wine? Of the forest’s resinous fragrance ... modernised Spiegelsaal rooms and the sweet sensuality of roses? Of cool, invigorating water making our skin tingle ... new smoker's lounge with pleasure? Of stimulating conversations or simply the quiet hum of bees? ... new access roads In the heart of the Black Forest – and close to Baden-Baden (50km), Strasbourg (50km), ... even more EXPERIENCES ... Freiburg (70km), Offenburg (33km) and Freudenstadt (25km) – we have created a refuge of abundant space and time for you to indulge yourself ... or simply relax, take With kind regards from Meinrad Schmiederer, the Schmiederer and Herrmann in the view, and breathe. families, and the Dollenberg team 2 3 Explorers and adventurers reconnoitre the Black Forest uplands on the Kniebis, survey the River Rench and discover the wonders of the Black REENERGISE AND REVITALISE ON A HIKE Forest National Park. Families go on a fairy-tale treasure hunt and stalk hidden forest dwellers. In the superb hiking region of Bad Peterstal-Griesbach: The Dollenberg’s hiking package Our weekly programme opens up a whole world of hiking, Hiking maps: complimentary Black Forest hiking map for outdoor but we can also help you plan your own, self-guided hike. -

Imperial and Free Towns of the Holy Roman Empire City-States in Pre-Modern Germany?

Imperial and Free Towns of the Holy Roman Empire City-States in Pre-Modern Germany? Peter Johanek (Respondent: Martina Stercken) The imperial and free towns of Germany are a phen speaking of the German monarchs, as most of their omenon not to be found elsewhere in pre-modem contemporaries did. Europe, and they are a special feature of German con To be the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, stitutional history. So, before looking at the main issue which was seen as a continuation of the ancient of this paper, we have to discuss briefly the general Roman Empire, transferred first to the Franks (800) setting of these “city-states”, i.e. the constitutional and then to the Germans (962), was also seen as a vital framework of the “Holy Roman Empire” during the factor to salvation history, and accordingly it provided late Middle Ages and in early modern times, viz. ca. a ruler with an unquestionable legitimacy. But in 1200-1800.1 The Empire was not a centralised reality the emperor had little power and only a few monarchy like the kingdoms of Western Europe, espe instruments were at his disposal to exercise power. In cially England and France. Its political structure was the late Middle Ages and in early modern times there determined by regional forces, particularly the was no royal demesne which was handed down from dynastic territories that emerged in the course of the one monarch to the next. What territorial power an 13th century, as well as by the ecclesiastical territories emperor had, lay in the territories over which he ruled (bishoprics, a great number of important monasteries as a prince. -

Volume 1. from the Reformation to the Thirty Years War, 1500-1648 Peace Treaties of Westphalia (October 14/24, 1648)*

Volume 1. From the Reformation to the Thirty Years War, 1500-1648 Peace Treaties of Westphalia (October 14/24, 1648)* In 1643, negotiations began on a general peace to end the Thirty Years War. The Peace of Westphalia, signed five years later, was actually two treaties, each negotiated in a different seat of an Imperial prince-bishop in the land of Westphalia. On October 14/24, 1648, the treaty between Emperor Ferdinand III and Queen Christina of Sweden and their respective allies was signed at Osnabrück (see part A, below); on the same day, the treaty between Ferdinand III and King Louis XIV of France and their respective allies was signed at Münster (see part B). For the Holy Roman Empire, the Peace meant a settlement to the political and territorial disputes that had begun with the German Reformation and an end to the conflicts sparked by the Bohemian conflict of 1618 and the Swedish invasion of June 1631. The excerpt from the Treaty of Osnabrück confirmed: the Empire’s character as aristocratic- corporate state governed by the emperor and the Imperial estates, which enjoyed a new but limited right to relations with foreign powers (Art. VIII, §2); the international expansion of the Imperial estates with the admission of Sweden (Art. X, §9), whose monarch acquired territorial reparations in the form of half of Pomerania and other lands (Art. X); Brandenburg’s acquisition of the prince-archbishopric of Magdeburg and the other half of Pomerania (Art. XI-XIV); Bavaria’s retention of the Upper Palatinate and the electoral title from the Palatine line of the Wittelsbachs (Art.