Fear of a Black Planet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derrick Bell: Godfather Provocateur André Douglas Pond Cummings University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H

University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law Masthead Logo Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives Faculty Scholarship 2012 Derrick Bell: Godfather Provocateur andré douglas pond cummings University of Arkansas at little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Judges Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation andré douglas pond cummings, Derrick Bell: Godfather Provocateur, 28 Harv. J. Racial & Ethnic Just. 51 (2012). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DERRICK BELL: GODFATHER PROVOCATEUR andrg douglas pond cummings* I. INTRODUCTION Professor Derrick Bell, the originator and founder of Critical Race The- ory, passed away on October 5, 2011. Professor Bell was 80 years old. Around the world he is considered a hero, mentor, friend and exemplar. Known as a creative innovator and agitator, Professor Bell often sacrificed his career in the name of principles and objectives, inspiring a generation of scholars of color and progressive lawyers everywhere.' Bell resigned a tenured position on the Harvard Law School faculty to protest Harvard's refusal to hire and tenure women of color onto its law school -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

Underground Rap Albums 90S Downloads Underground Rap Albums 90S Downloads

underground rap albums 90s downloads Underground rap albums 90s downloads. 24/7Mixtapes was founded by knowledgeable business professionals with the main goal of providing a simple yet powerful website for mixtape enthusiasts from all over the world. Email: [email protected] Latest Mixtapes. Featured Mixtapes. What You Get With Us. Fast and reliable access to our services via our high end servers. Unlimited mixtape downloads/streaming in our members area. Safe and secure payment methods. © 2021 24/7 Mixtapes, Inc. All rights reserved. Mixtape content is provided for promotional use and not for sale. The Top 100 Hip-Hop Albums of the ’90s: 1990-1994. As recently documented by NPR, 1993 proved to be an important — nay, essential — year for hip-hop. It was the year that saw 2Pac become an icon, Biz Markie entangled in a precedent-setting sample lawsuit, and the rise of the Wu-Tang Clan. Indeed, there are few other years in hip- hop history that have borne witness to so many important releases or events, save for 1983, in which rap powerhouse Def Jam was founded in Russell Simmons’ dorm room, or 1988, which saw the release of about a dozen or so game-changing releases. So this got us thinking: Is there really a best year for hip-hop? As Treble’s writers debated and deliberated, we came up with a few different answers, mostly in the forms of blocks of four or five years each. But there was one thing they all had in common: they were all in the 1990s. Now, some of this can be chalked up to age — most of Treble’s staff and contributors were born in the 1980s, and cut their musical teeth in the 1990s. -

Public Enemy's Views on Racism As Seen Trough Their Songlyrics Nama

Judul : Public enemy's views on racism as seen trough their songlyrics Nama : Rasti Setya Anggraini CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of Choosing The Subject Music has become the most popular and widespread entertainment product in the world. As the product of art, it has performed the language of emotions that can be enjoyed and understood universally. Music is also well known as a medium of expression and message delivering long before radio, television, and sound recordings are available. Through the lyrics of a song, musicians may express everything they want, either their social problems, political opinions, or their dislike toward something or someone. As we know, there are various music genres existed in the music industries nowadays : such as classic, rock, pop, jazz, folk, country, rap, etc. However, not all of them can be used to accommodate critical ideas for sensitive issues. Usually, criticism is delivered in certain music genre that popular only among specific community, where its audience feels personal connection with the issues being criticized. Hip-hop music belongs to such genre. It served as Black people’s medium 1 2 for expressing criticism and protest over their devastating lives and conditions in the ghettos. Yet, hip-hop succeeds in becoming the most popular mainstream music. The reason is this music, which later on comes to be synonym with rap, sets its themes to beats and rivets the audience with them. Therefore, for the audiences that do not personally connected with black struggle (like the white folks), it is kind of protect them from its provocative message, since “it is possible to dig the beats and ignore the words, or even enjoy the words and forget them when it becomes too dangerous to listen” (Sartwell, 1998). -

The Socio-Political Influence of Rap Music As Poetry in the Urban Community Albert D

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2002 The socio-political influence of rap music as poetry in the urban community Albert D. Farr Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Farr, Albert D., "The ocs io-political influence of rap music as poetry in the urban community" (2002). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 182. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/182 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The socio-political influence of rap music as poetry in the urban community by Albert Devon Farr A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Program of Study Committee Jane Davis, Major Professor Shirley Basfield Dunlap Jose Amaya Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2002 Copyright © Albert Devon Farr, 2002. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Albert Devon Farr has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy Ill My Dedication This Master's thesis is dedicated to my wonderful family members who have supported and influenced me in various ways: To Martha "Mama Shug" Farr, from whom I learned to pray and place my faith in God, I dedicate this to you. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Public Enemy 2013.Pdf

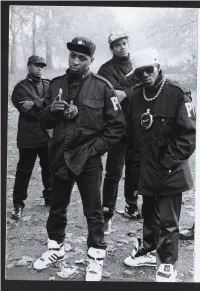

PERFORMERS Due to Public Enemy’s work, hip-hop established itself as a global force. ------------------------------------------- ---------------------------- By Alan Light _________________________________ UN-DM C had a more revolutionary impact on the way records are made. N.W . A spawned more imitators. The Death Row and Bad Boy juggernauts sold more R albums. Jay-Z has topped the charts for many more years. But no act in the history of hip-hop ever felt more important than Public Enemy. A t the top o f its game, PE redefined not just what a rap group could accomplish, but also the very role pop musicians could play in contemporary culture. Lyrically, sonically, politi cally, onstage, on the news - never before had musicians been considered “radical” across so many different platforms. The mix of agitprop politics, Black Panther-meets-arena-rock packaging, high drama, and low comedy took the group places hip-hop has never been before or since. For a number of years in the late eighties and early nineties, it was, to sample a phrase from the Clash, the only band that mattered. I put them on a level with Bob Marley and a handful of other artists,” wrote the late Adam Yauch (the Beastie Boys were one of Public Enemy's earliest champions). “[It’s a] rare artist who can make great music and also deliver a political and social message. But where Marley’s music sweetly lures you in, then sneaks in the message, Chuck D grabs you by the collar and makes you listen.” Behind, beneath, and around it all was that sound. -

Rap, Racecraft, and MF Doom

humanities Article Keeping It Unreal: Rap, Racecraft, and MF Doom J. Jesse Ramírez School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of St Gallen, 9000 St. Gallen, Switzerland; [email protected] Abstract: Focusing on the masked rapper MF Doom, this article uses Karen E. Fields and Barbara J. Fields’s concept of “racecraft” to theorize how the insidious fiction called “race” shapes and reshapes popular “Black” music. Rap is a mode of racecraft that speculatively binds or “crafts” historical musical forms to “natural,” bio-geographical and -cultural traits. The result is a music that counts as authentic and “real” to the degree that it sounds “Black,” on the one hand, and a “Blackness” that naturally expresses itself in rap, on the other. The case of MF Doom illustrates how racialized peoples can appropriate ascriptive practices to craft their own identities against dominant forms of racecraft. The ideological and political work of “race” is not only oppressive but also gives members of subordinated “races” a means of critique, rebellion, and self-affirmation—an ensemble of counter- science fictions. Doom is a remarkable case study in rap and racecraft because when he puts an anonymous metal mask over the social mask that is his ascribed “race,” he unbinds the latter’s ties while simultaneously revealing racecraft’s durability. Keywords: race; racecraft; rap; hip-hop; science fiction; MF Doom; King Geedorah; Viktor Vaughn; Doctor Doom; KMD The history of blackness is testament to the fact that objects can and do resist. —Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (p. -

Carlton Douglas Ridenhour (Born August 1, 1960), Known Professionally As Chuck D, Is an American Rapper, Author, and Producer. A

Carlton Douglas Ridenhour (born August 1, 1960), known professionally as Chuck D, is an American rapper, author, and producer. As the leader of the rap group Public Enemy, he helped create politically and socially conscious hip hop music in the mid 1980s. Chuck D has a powerful, resonant voice that is often acclaimed as one of the most distinct and impressive in hip-hop. About.com ranked him at No. 9 on their list of the Top 50 MCs of All Time, while The Source ranked him at No. 12 on their list of the Top 50 Hip-Hop Lyricists of All Time. Ridenhour was born in Queens, New York. He began writing rhymes after the New York City blackout of 1977. After graduating from Roosevelt Junior-Senior High School, he went to Adelphi University on Long Island to study graphic design, where he met William Drayton (Flavor Flav). He received a B.F.A. from Adelphi in 1984 and later received an honorary doctorate from Adelphi in 2013. While at Adelphi, Ridenhour co-hosted hip hop radio show the Super Spectrum Mix Hour as Chuck D on Saturday nights at Long Island rock radio station WLIR, designed flyers for local hip-hop events, and drew a cartoon called Tales of the Skind for Adelphi student newspaper The Delphian. Upon hearing Ridenhour's demo track "Public Enemy Number One", fledgling producer/upcoming music-mogul Rick Rubin insisted on signing him to his Def Jam label. Public Enemy’s major label albums were Yo! Bum Rush the Show (1987), It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988), Fear of a Black Planet (1990), Apocalypse 91.. -

Getting Hip to the Hop: a Rap Bibliography/Discography

Music Reference Services Quarterly. 1996, vol.4, no.4, p.17-57. ISSN: 1540-9503 (online) 1058-8167 (print) DOI: 10.1300/J116v04n04_02 http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/wmus20/current http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/wmus20/4/4 © 1996 The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved. Getting Hip to the Hop: A Rap Bibliography/Discography Leta Hendricks ABSTRACT. This bibliographic/discographic essay examines works which may be used to develop a core collection on Rap music. A selected bibliography and discography is also provided. INTRODUCTION Research interest has recently emerged in the popular African-American musical idiom known as Rap and continues to grow as social and cultural scholars have embarked on a serious study of Rap music and culture. Therefore, the student, scholar, and general library patron may seek information on Rap and its relationship with the African-American community. During the 1970's, libraries rushed to include in their holdings culturally diverse materials, especially materials on African-American history, literature, and culture. Today, emphasis is placed on cultural diversity, Rap is sometimes deemed to be low art and may be overlooked in the collecting of diverse materials. However, Rap has already celebrated its sixteenth anniversary and, like Rock and Roll, Rap is here to stay. Rap music research is difficult because (1) the librarian or information provider generally lacks knowledge of the category,' and (2) primary/ephemeral materials are not widely accessible.2 This selective bibliographic and discographic essay examines a variety of Rap resources and materials including biographies, criticisms, discographies, histories, recordings, and serials to help fill the Rap knowledge and culture gap and assist in the development of a core collection on Rap music. -

Using Outside Sources: Quoting, Paraphrasing, Summarizing, and Citing

Using Outside Sources: Quoting, Paraphrasing, Summarizing, and Citing Two General Reasons to Use Outside Sources 1. Support and Strengthen Your Argument: If the source agrees with you, if it supports your position, you make an implicit claim along the lines of “Hey, I’m not the only one who feels this way and/or believes this. See, someone else who also has authority in regard to this particular issue also supports this position.” Additionally, another reason parietals are so well-loved among Notre Dame students relates to how difficult they make group projects. For instance, my English class, “Reasons Shakespeare, Like, Totally Rocks,” requires my classmates and me to present in small groups at least three times a semester. Not only do we love having to find open times in our busy schedules to meet outside of class, but we especially appreciate having to leave our dorm rooms partway through our planning sessions, because our sessions overlap with when parietals begin on weeknights. Tanya Jones, one of my “Shakespeare Rocks” classmates, explains that she especially likes having to vacate her Lyons Hall dorm room when she and her groupmates are right in the middle of their project. “It’s great,” she declares, “to have to gather up all of our books, notes, computers, and other materials and move to the lounge on the first floor. Interruptions? Bring ’em on!” she adds with a smile. Thus, because group projects are too easy to begin with, Notre Dame should maintain parietals to make such projects far more challenging and annoying. 2. Act as a Counter or Foil to Your Argument If the source disagrees with you, you can use the source as a representative example of a position that may seem reasonable at first, at least to some audiences, but upon further examination, the position is revealed to be flawed: Many people believe, for instance, that today’s college students are lazy and entitled, feeling the world owes them something. -

1 from the Cambridge Companion to Pop and Rock Simon Frith and William Straw, Editors Soul Into Hip-Hop Russell A. Potter Rhode

From The Cambridge Companion to Pop and Rock Simon Frith and William Straw, editors Soul into Hip-Hop Russell A. Potter Rhode Island College Call it soul, call it funk, call it hip-hop; the deep-down core of African-American popular music has been both a center to which performers and audiences have continually returned, and a centrifuge which has sent its styles and attitudes outwards into the full spectrum of popular music around the world. The pressure -- both inward and outward -- has often been kept high by an American music industry slow to move beyond the apartheid-like structures of its marketing systems, which, though ostensibly abandoned in the days since the "race records" era (the 1920's through the 1950's), continue to shadow the industry's practices. However much cross-over there has been between black and white audiences, the continual reiteration of racial and generic boundaries in radio formats, retailing, and chart-making has again and again forced black artists and producers to navigate between a vernacular aesthetic (often invoked as "the street") and what the rapper Guru calls "mass appeal" -- the watering-down of style targeted at an supposedly "broader" (read: white) audience. So it has been that, within black communities, there has been an ongoing need to name and claim a music whose strategic inward turns refused what was often seen as a "sell-out" appeal to white listeners, a music that set up shop right in the neighborhood, via black (later "urban contemporary") radio, charts, and retailers, and in the untallied vernacular traffic in dubbed tapes, DJ mixes, and bootlegs.