Causation - in Context: an Afterword

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(ABSOLUTE) LIABILITY TORTS • General Rule

STRICT (ABSOLUTE) LIABILITY TORTS • General rule: • A defendant may be held liable in the absence of an intention to act or negligence in acting IF his conduct (or the conduct of those with whom he shares a special legal relationship) causes the Plaintiff loss or injury. • Strict liability: • Under the doctrine of strict liability, the Defendant may be held liable without acting intentionally, carelessly or unreasonably • In some instances, defences can be raised • (eg): employers are liable for the actions of their employees if they commit an act that results in loss or injury during the course and scope of their employment • Absolute liability: • Commission of a certain act serves as proof of a Tortious action resulting in liability • The essential issue is causation and not fault • There are no defences that can be raised • Vicarious Liability: • Several forms of vicarious liability: 1) Statutory Vicarious liability - (s192 Ontario Highway Traffic Act) – an owner of a vehicle accepts liability for any other driver using it with their knowledge - (Yeung v Au) 2) Principal/Agent relationship - A principal may be held liable for the Torts committed by an agent 3) Employer/Employee relationship - A Court can hold an employer liable, and an employee personally liable. - The doctrine of vicarious liability provides the Plaintiff with an alternative source of relief – this does not mean that the employee is relieved of responsibility. • I.R.A.C: (employer/employee relationship) • Issue: - The question is whether … (BASED ON THE EXAM PAPER…!!!) • Rule: - a Court can hold an employer vicariously liable, and an employee personally liable for the actions of the employee. -

Cattle Tresspass

CATTLE TRESSPASS The owner of the capital may be held liable if his cattle commit trespass on the land of another person. It is an ancient common law tort whereby the keeper of livestock was held strictly liable for any damage caused by the straying livestock. The liability in such case is strict and the owner of the cattle is liable even if the vicious propensity of the cattle and, owner’s knowledge of the same are not proved. There is also no necessity of proving negligence on the part of the defendant. Liability for cattle trespass is similar to, but conceptually distinct from, the old common law scienter action in relation to strict liability for animals which are known to be vicious. In many of the reported cases, claims for cattle trespass and scienter are pleaded in the alternative. Cattle for the purpose include bulls, cows, sheep, pigs, horses, asses and poultry. Dogs and cats are not included in the term and, therefore there cannot be cattle trespass by dogs and cats. In Buckle v. Holmes,1 the defendant’s cat strayed into the plaintiff’s land and there it killed thirteen pigeons and two bantams. Killing of birds was nothing peculiar to this cat alone, therefore, the liability under the scienter rule did not arise. There was no liability even for cattle trespass because cat is no ‘cattle’ for the purpose of this rule. The same is the position in case of a dog.2 The liability for cattle trespass is strict, scienter or negligence on the part of the owner of the cattle is not required to be proved. -

Cattle Trespass and the Rights and Responsibilities of Biotechnology Owners

Osgoode Hall Law Journal Article 5 Volume 46, Number 2 (Summer 2008) Containing the GMO Genie: Cattle rT espass and the Rights and Responsibilities of Biotechnology Owners Katie Black James Wishart Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj Part of the Environmental Law Commons Commentary Citation Information Black, Katie and Wishart, James. "Containing the GMO Genie: Cattle rT espass and the Rights and Responsibilities of Biotechnology Owners." Osgoode Hall Law Journal 46.2 (2008) : 397-425. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol46/iss2/5 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Osgoode Hall Law Journal by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Containing the GMO Genie: Cattle rT espass and the Rights and Responsibilities of Biotechnology Owners Abstract Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) have caused substantial economic losses by contaminating non- GMO crops and threatening the economic self-determination of non-GMO farmers. After Monsanto v. Schmeiser, biotech IP owners hold most of the rights in the property "bundle" with respect to bioengineered organisms. This commentary highlights the disequilibrium between these broad patent rights and the lack of legal responsibility for harms caused by GMO products. The uthora s propose that there is a role for tort law-- specifically the tort of cattle trespass--in fairly allocating risk and responsibility. The doctrine of cattle trespass reflects a policy of distributive justice, positing that the unique risks associated with keeping living creatures ought to import liability based on the owner's creation and control of those risks. -

Winfield Tort

WINFIELD ON TORT EIGHTH EDITION BY J. A. JOLOWICZ, M.A. Of the Inner Temple and Gray's Inn, Barrister-at-Law; Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge; Lecturer in Law of the University of Cambridge AND T. ELLIS LEWIS, B.A., LL.M., PH.D. Of Gray's Inn, Barrister-at-Law; Fellow of Trinity Hall, Cambridge; Lecturer in Law in the University of Cambridge LONDON SWEET & MAXWELL 4967 CONTENTS page Preface vii Table of Cases xiii Table of Statutes xlvii References to Year Books lv 1. MEANING OF THE LAW OF TORT 1 The Foundation of Tortious Liability .... 10 2. GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF TORTIOUS LIABILITY . 14 Act or Omission 16 Intention or Negligence or the Breach of a Strict Duty . 16 Motive and Malice 20 3. NOMINATE TORTS 24 4. TRESPASS TO THE PERSON . .27 Assault and Battery 27 False Imprisonment 32 Intentional Physical Harm other than Trespasses to the Person 40 5. NEGLIGENCE 42 Essentials of Negligence 42 Trespass to the Person and Negligence .... 76 6. REMOTENESS OF DAMAGE AND CONTRIBUTORY NEGLIGENCE . 80 Remoteness of Damage 80 Contributory Negligence 102 7. NERVOUS SHOCK 118 8. BREACH OF STATUTORY DUTY 128 The Existence of Liability 128 Elements of the Tort 134 Defences 138 Nature of the Action 140 9. EMPLOYERS' LIABILITY 143 Introductory 143 Common Law 147 Breach of Statutory Duty 158 Employers' Liability 164 10. LIABILITY FOR LAND AND STRUCTURES . .168 Introduction 168 The Common Law 169 The Occupiers' Liability Act 1957 177 ix X CONTENTS 10. LIABILITY FOR LAND AND STRUCTURES—continued Liability to Trespassers 192 Liability to Children 199 Liability of Non-Occupiers 207 11. -

JIJUN YIN, Petitioner/Plaintiff-Appellant, Vs. PI

***FOR PUBLICATION IN WEST’S HAWAII REPORTS AND PACIFIC REPORTER*** Electronically Filed Supreme Court SCWC-15-0000325 09-MAR-2020 10:49 AM IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF HAWAII ---o0o--- JIJUN YIN, Petitioner/Plaintiff-Appellant, vs. P.I. AGUIAR, AS PERSONAL REPRESENTATIVE OF VIRGINIO C. AGUIAR, JR., DECEASED, KEVIN AGUIAR and AGEE, INC., Respondents/Defendants-Appellees. SCWC-15-0000325 CERTIORARI TO THE INTERMEDIATE COURT OF APPEALS (CAAP-15-0000325; CIV. NO. 11-1-0331) MARCH 9, 2020 RECKTENWALD, C.J., NAKAYAMA, McKENNA, POLLACK, AND WILSON, JJ. OPINION OF THE COURT BY POLLACK, J. In this case, the Petitioner filed a complaint in the Circuit Court of the Third Circuit (circuit court) alleging that the Respondent’s cattle trespassed onto his property causing damage to his sweet potato crop. In granting the Respondent’s motion for summary judgment, the circuit court concluded that ***FOR PUBLICATION IN WEST’S HAWAII REPORTS AND PACIFIC REPORTER*** the Petitioner’s land was neither “properly fenced” nor “unfenced,” and therefore Hawaii’s statutory law governing the trespass of livestock onto cultivated land did not apply to the Petitioner’s property. Further, the circuit court determined that a provision in the Petitioner’s lease, making the Petitioner fully responsible for keeping cattle out of his cultivated land, was not void against public policy. The Intermediate Court of Appeals affirmed the circuit court’s judgment. Upon review of the legislative history of the statutes that govern the trespass of livestock onto the cultivated land of another, we conclude that the legislature intended to hold owners of livestock liable for the damage caused by the trespass of their animals on cultivated land whether the land is properly fenced or not. -

The Law Commission

THE LAW COMMISSION CIVIL LIABILITY FOR ANIMALS Laid before Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 LONDON HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE PRICE 5s. 6d. NET LAW COM. No. 13 The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commis- sioners are- The Honourable Mr. Justice Scarman, O.B.E., Chairman. Mr. L. C. B. Gower, M.B.E. Mr. Neil Lawson, Q.C. Mr. N. S. Marsh, Q.C. Mr. Andrew Martin, Q.C. Mr. Arthur Stapleton Cotton is a special consultant to the Commission. The Secretary of the Commission is Mr. H. Boggis-Rolfe, C.B.E., and its offices are at Lacon House, Theobald’s Road, London, W.C.l. 2 CONTENTS Page A. Introduction . 5 B. The General Principles of Liability . 6 (a) Strict Liability for Dangerous Animals . 6 (b) Suggestions for the Refom of Strict Liability for Dangerous Animals . 8 (c) Recommendations of the Law Commission on Strict Liability for Dangerous Animals . 10 (d)The General Liability for Negligence . 16 (e) The Searle v. Wallbanlc Exception to Liability for Negligence 17 (f)Trespassers and Liability for Negligence in respect of Animals . 26 (g) Summary of Recommendations regarding Liability for Negligence . 27 C. Liability for Cattle Trespass . 27 D. DistressDamageFeasant . , . 30 E. The Dogs Acts 1906 to 1928 . 32 F. The Person Liable for Injury or Damage inflicted by Animals . 33 G. The Protection of Livestock against Dogs . 35 H. -

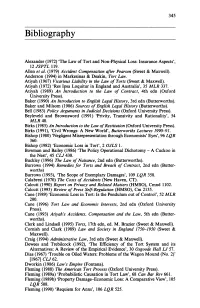

Bibliography

345 Bibliography Alexander (1972) 'The Law of Tort and Non-Physical Loss: Insurance Aspects', 12 JSPTL 119. Allen et al. (1979) Accident Compensation after Pearson (Sweet & Maxwell). Anderson (1994) in Markesinas & Deakin, Tort Law. Atiyah (1967) Vicarious Liability in the Law of Torts (Sweet & Maxwell). Atiyah (1972) 'Res Ipsa Loquitur in England and Australia', 35 MLR 337. Atiyah (1989) An Introduction to the Law of Contract, 4th edn (Oxford University Press). Baker (1990) An Introduction to English Legal History, 3rd edn (Butterworths). Baker and Milsom (1986) Sources of English Legal History (Butterworths). Bell (1983) Policy Arguments in Judicial Decisions (Oxford University Press). Beyleveld and Brownsword (1991) 'Privity, Transivity and Rationality', 54 MLR48. Birks (1985) An Introduction to the Law of Restitution (Oxford University Press). Birks (1991), 'Civil Wrongs: A New World', Butterworths Lectures 1990-91. Bishop (1980) 'Negligent Misrepresentation through Economists' Eyes', 96 LQR 360. Bishop (1982) 'Economic Loss in Tort', 2 OJLS 1. Bowman and Bailey (1986) 'The Policy Operational Dichotomy - A Cuckoo in the Nest', 45 CLJ 430. Buckley (1996) The Law of Nuisance, 2nd edn (Butterworths). Burrows (1994) Remedies for Torts and Breach of Contract, 2nd edn (Butter- worths) Burrows (1993), 'The Scope of Exemplary Damages', 109 LQR 358. Calabresi (1970) The Costs of Accidents (New Haven, CT). Calcutt (1990) Report on Privacy and Related Matters (HMSO), Cmnd 1102. Calcutt (1993) Review of Press Self-Regulation (HMSO), Cm 2135. Cane (1989) 'Economic Loss in Tort: Is the Pendulum out of Control', 52 MLR 200. Cane (1996) Tort Law and Economic Interests, 2nd edn (Oxford University Press). Cane (1993) Atiyah's Accidents, Compensation and the Law, 5th edn (Butter worths). -

TORTICLES Nominate Torts

r991-921 TORTICLES 105 TORTICLES Bernard Rudden* "Both major systems of law in the opening decades of the nineteenth century had to meet new problems with old tools: the French with a wide standard of liability; the British and Americans with a pigeonhole system of nominate torts." F.F. Stone.l Professor Stone's observations describe the early nineteenth century. Almost two hundred years later, very little has changed. This small tribute to his memory speculates on the reasons for the persistence of the pattern. The first part offers a very general comparison of the intellectual and foreniic approach to modern tort problems of the French on the one hand, and, on the other, of the common-law family. The second part attempts something not, apparently, done before: an alphabetical list of known torts. The third part considers the reasons for, and some consequences of, the cornmon law's style of problem solving in this area of law. A Brief Comparison - Tltiq paper's title coins a diminutive to express a curious characteristic of the common law, and one on which attention will be focused. Nonetheless, as a preliminary contrast it is worth recalling, in very general terms, the striking features of the modern French position. ryryi1S asiderecent statutory intervention covering motor vehicles and defective products, liability in private law is attributed on a few broad glounds: that damage was caused deliberately or carelessly; or by a thing in the tortfeasor's custdyi2 or by someone (employee or child) * LL.D. (Cambridge). D.C.L. (Oxford). Ph.D. (Wales). LL.D. -

Ruminations on the Role of Fault in the History of the Common Law of Torts Wex S

Louisiana Law Review Volume 31 | Number 1 December 1970 Ruminations on the Role of Fault in the History of the Common Law of Torts Wex S. Malone Repository Citation Wex S. Malone, Ruminations on the Role of Fault in the History of the Common Law of Torts, 31 La. L. Rev. (1970) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol31/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RUMINATIONS ON THE ROLE OF FAULT IN THE HISTORY OF THE COMMON LAW OF TORTS* Wex S. Malone** Any attempt to assign negligence its proper role in the his- tory of tort law must be deferred until a determination of the role that fault in any of its varieties played in early law. Even this deferment does not lead us back far enough, for we must also ask whether we can isolate a distinct role for tort law itself in the dawn of the history of the common law. The answer here must be clearly, No, if by "torts" we mean some sort of organized scheme for determining when and under what conditions the monetary costs of a harm suffered by one person should be shifted to the shoulders of another by means of some authori- tative order. The very prospect of a civil suit for damages pre- supposes a sophistication that simply did not exist in the earliest half-organized legal societies. -

The Canadian Approach to Negligent Misrepresentation: a Critique of the Reliance Model of Liability

THE CANADIAN APPROACH TO NEGLIGENT MISREPRESENTATION: A CRITIQUE OF THE RELIANCE MODEL OF LIABILITY by John Fairlie B.Mus. (1978), LL.B. (1982), The University of British Columbia A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Faculty of Law) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia August 2003 ©John Fairlie, 2003 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of ^.r^^x^a, ^-U A^OQ ^ ^TV<Lo b.^p ^<VJ The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date Ao^u-V" 2.q j ?J^CN^ DE-6 (2/88) 11 ABSTRACT The Canadian Approach to Negligent Misrepresentation: A Critique of the Reliance Model of Liability by John Fairlie This thesis is presented on recent developments in the law of negligent misrepresentation in Canada, focusing on the debate surrounding the appropriate basis of liability and its significance in commercial settings. Since Hedley Byrne first opened up the law of negligence to careless words and economic loss, there has been some confusion as to the precise nature of the duty of care. -

Chapter 3: Intentional Invasion of Land

3 Intentional Invasion of Land Trespass [3.10] From earliest times the common law protected the possessory rights of landlords against unauthorised entry by an action of trespass, known as quare clausum fregit. The remedy was not, as its name might suggest, confined to intrusions upon enclosed lands because, says Blackstone, “every man’s land is in the eye of the law inclosed and set apart from his neighbour’s.” 1 In the course of its history, this action of trespass came to be used for a number of different purposes which have left their mark on its conditions of liability. In origin, trespass was a remedy for forcible breach of the King’s peace, aimed against acts of intentional aggression. This early association with the maintenance of public order explains why the action lies only for interference with an occupier’s actual possession. Its proprietary aspect became more dominant when it was later used for the purpose of settling boundary disputes, quieting title and preventing the acquisition of easements by prescriptive user. 2 These latter functions account for the rule that the plaintiff is not required to prove material loss, 3 and that a mistaken belief by the defendant that the land was his affords no excuse. 4 The temptation for the occupier to resort to violence in defence of his boundary and privacy was not lessened by the absence of pecuniary loss, while in less serious cases nominal damages were justified to vindicate his rights against adverse claims. Likewise, if mistake as to title had been admitted as a defence, trespass would have been a less suitable remedy for settling claims to disputed land. -

The English Law of Tort

The English Law of Tort John Hodgson MA (Cambridge); LLM (Cambridge); Solicitor; Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. Reader in Legal Education, Nottingham Law School, Nottingham Trent University. Co-author Hodgson & Lewthwaite Tort Law (Oxford University Press) [email protected] Overview of the programme: Monday 24th October 2011: Session One: Origins and conceptual framework. Trespass Torts. Tuesday 25th October: Session Two: The evolution of the Tort of negligence/breach of duty from actions on the case via Donoghue v Stevenson to Caparo v Dickman. Wednesday 26th October: Session Three: The concept of causation in Tort - difficulties and solutions. Session Four: Special situations in negligence: - Economic Loss, Psychiatric Harm, Occupier's Liability and Employer's liability. Thursday 27th October: Session Five: Nuisance Torts. Remedies - damages and injunctions. Session Six: International aspects - jurisdiction, forum conveniens and the Brussels and Rome II regulations. Session One: Origins and conceptual framework. Trespass Torts. Origins and conceptual framework. A study of early legal history shows that legal systems typically cover a range of topics, which in modern terminology correspond to the law of persons, the law of property, and the law of obligations, as we can see them in modern European Civil Codes. At this stage, among the obligations we find a number of sub-categories. Contractual obligations are identified as those where the obligation arises out of the choice of the parties. In Roman law these are regarded as bonds arising out of a formal undertaking. Tortious obligations are those arising from a vinculum juris, a bond arising from the general legal expectations of the society, not from a private arrangement.