Chapter One: General Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecology of Feral Pigeons: Population Monitoring, Resource Selection, and Management Practices Erin E

Chapter Ecology of Feral Pigeons: Population Monitoring, Resource Selection, and Management Practices Erin E. Stukenholtz, Tirhas A. Hailu, Sean Childers, Charles Leatherwood, Lonnie Evans, Don Roulain, Dale Townsley, Marty Treider, R. Neal Platt II, David A. Ray, John C. Zak and Richard D. Stevens Abstract Feral pigeons (Columba livia) are typically ignored by ornithologists but can be found roosting in the thousands within cities across the world. Pigeons have been known to spread zoonoses, through ectoparasites and excrement they produce. Along with disease, feral pigeons have an economic impact due to the cost of cleanup and maintenance of human infrastructure. Many organizations have tried to decrease pigeon abundances through euthanasia or use of chemicals that decrease reproductive output. However, killing pigeons has been unsuccessful in decreasing abundance, and chemical inhibition can be expensive and must be used throughout the year. A case study at Texas Tech University has found that populations fluctu- ate throughout the year, making it difficult to manage numbers. To successfully decrease populations, it is important to have a multifaceted approach that includes removing necessary resources (i. e. nest sites and roosting areas) and decreasing the number of offspring through humane techniques. Keywords: birth control, nest sites, nuisance, rock doves, zoonoses 1. Introduction Of the 7.53 billion people that live on Earth, over half inhabit cities [1, 2]. Increase in development has altered biodiversity through an increase in fragmenta- tion and invasive species abundance. Urban areas are highly susceptible to invasions of nonnative species [3], which can increase threat to native species and increase economic costs due to environmental and structural damage [4, 5]. -

Ecology of Feral Pigeon (Columba Livia) in Urban Areas of Rawalpindi/ Islamabad, Pakistan

Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 45(5), pp. 1229-1234, 2013 Ecology of Feral Pigeon (Columba livia) in Urban Areas of Rawalpindi/ Islamabad, Pakistan Sakhawat Ali,*1 Bushra Allah Rakha,1 Iftikhar Hussain,1 Muhammad Sajid Nadeem2 and Muhammad Rafique3 1Department of Wildlife Management, Pir Mehr Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi-46300, Pakistan 2Department of Zoology, Pir Mehr Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi-46300, Pakistan 3Zoological Division, Pakistan Museum of Natural History, Islamabad, Pakistan Abstract.- This study was designed to study the ecology of feral pigeon (Columba livia) in the urban areas of Rawalpindi/Islamabad, Pakistan. Seasonal changes in population density, sex ratio, age group, roosting sites, nesting sites, food and water points of pigeons were recorded in Rawalpindi/Islamabad. Higher population density of the pigeon in Islamabad was recorded in winter season followed by autumn, spring and summer season (0.13, 0.13, 0.10 and 0.09 individuals/ha respectively) whereas the higher population density of the pigeon in Rawalpindi was found in summer season followed by winter, spring and autumn (0.13, 0.11, 0.11 and 0.10 individuals/ha, respectively). The male and female sex ratio of the pigeon population confirms 1:1 sex ratio, both in Rawalpindi/Islamabad in different seasons. However, adult and juvenile numbers in the pigeon population did not follow 1:1 ratio; adults were more than juveniles in Rawalpindi/Islamabad in all seasons. The roosting sites, nesting sites, food and water points did differ in different seasons in Islamabad. Highest population of the pigeon was recorded in old buildings (0.30 individual/ha) and lowest in parklands (0.008 individual/ha). -

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT TIPS for Dealing with BIRD PESTS

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT TIPS for dealing with BIRD PESTS Lynn Braband, NYSIPM Program of Cornell University As a culture, we have always valued wildlife. Despite that, many animals have been hunted or culled in such a manner as to decimate populations. The goal of wildlife management is, according to Dan Decker of Cornell University, “ . to maximize the benefits of wildlife while minimizing the costs of wildlife. Points to consider when dealing with wildlife are: Is there a problem that is significant enough to make action necessary? Do you know the laws concerning management of this particular animal? Have you considered health and safety aspects? Is the pest animal causing health or safety concerns to people or facilities? Will the ensuing management treatment cause any health or safety concern? Are the proposed treatments humane? While we don’t object to most treatments of insect pests, the management of vertebrate wildlife pests objectionable? Is the treatment effective? What information did you find to support your choice of management treatment? Is the treatment practical? Is the cost worth the result? Is it sustainable in time and cost needed? How would the management treatment be viewed by outsiders? “Act as if you are being videotaped.” What regulatory agencies have a say in wildlife management? The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is the regulatory agency dealing with bird management. The NYS DEC regulates wildlife management and has ECO (Environmental Conservation Officers) in the field. The NYS DEC is also the final say on Registered products (pesticides) including products not always considered ‘pesticides’ such as reproductive inhibitors. -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Rock Doves (Domestic & Feral Pigeons)

VERTEBRATE PEST CONTROL HANDBOOK - BIRDS BIOLOGY, LEGAL STATUS, CONTROL MATERIALS AND DIRECTIONS FOR USE Rock Doves (Domestic pigeons - also known as feral pigeons) Columba livia Family: Columbidae Introduction: Pigeons and doves share many common features, including small, rounded heads, small slim bills with a small fleshy patch at the base, rounded bodies with dense, soft feathers, tapered wings and short, scaly legs, and cooing or crooning calls. In fact, there is no strict division. The rock dove has long been domesticated and ‘escaped’ to live wild as the familiar town pigeon. There are many species all over the world. The rock dove was first introduced into North America in the 1600’s. Identification: The rock dove is a large pigeon. Their color varies, but the truly wild birds are gray. They have a white rump, rounded tail, usually with a dark tip. Their pale gray wings have two back bars. The sexes look alike although the male is slightly larger with more iridescence on the neck. Size: 11-14 inches. Distinctive sound is a continuous "Coo, recto-coo." Further information is available at: Cornell Lab of Ornithology The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds Legal Status: Feral pigeons are not protected by federal or state statute. However, the taking of Antwerp or homing pigeons (banded individuals) is a misdemeanor. VERTEBRATE PEST CONTROL HANDBOOK - BIRDS There may be local municipal restrictions on the methods used to take feral pigeons. Damage: In rural areas, pigeons can cause serious losses by their depredations on small grains and vegetables, contamination of foodstuffs, and potential dissemination of disease to domestic stock. -

Study of the Corpuscular Hematological Parameters Related to Growth, Development and Behavior of the Feral Pigeon

International Journal of Zoology and Applied Biosciences ISSN: 2455-9571 Volume 3, Issue 4, pp: 344-349, 2018 http://www.ijzab.com https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo Research Article STUDY OF THE CORPUSCULAR HEMATOLOGICAL PARAMETERS RELATED TO GROWTH, DEVELOPMENT AND BEHAVIOR OF THE FERAL PIGEON Saurabh Ranjan* and Gagan Kumar Thakur Department of Zoology, Sido Kanhu Murmu University, Dumka, Jharkhand, India. Article History: Received 24th July 2018; Accepted 1st August 2018; Published 17th August 2018 ABSTRACT Humans have observed birds from the earliest times and stone age drawings are among the oldest indications of an interest in birds. Many aspects of bird biology are difficult to study in the field. These include the study of behavioral and physiological changes that require a long duration of access to the bird. Studies in bird behavior include the use of tamed and trained birds in captivity. Studies on bird intelligence and song learning have been largely laboratory based. Studies of bird migration including aspects of navigation, orientation and physiology are often studied using captive birds in special cages that record their activities. The present study was designed with the following objectives to study and analyze corpuscular hematological parameters related to reproduction, growth, development and behavior of the domestic or feral pigeon. Keywords: Corpuscular hematological parameters, feral pigeon, Reproduction, Growth, Behavior, Feral pigeon. INTRODUCTION variations in corpuscular haematological parameters related to reproduction, growth, development and behavior of the The science of ornithology has a long history and studies domestic or feral pigeon (Fowler, 1990; Slater, 2003). on birds have helped develop several key concepts in evolution, behavior and ecology such as the definition of species, the process of speciation, instinct, learning, MATERIALS AND METHODS ecological niches, guilds, island biogeography, phylogeography and conservation (Mayr, 1984). -

Managing Urban Pest Bird Problems in Kentucky Thomas G

C O O P E R A T I V E E X T E N S I O N S E R V I C E U N I V E R S I T Y O F K E N T U C K Y • C O L L E G E O F A G R I C U L T U R E FOR-62 Managing Urban Pest Bird Problems in Kentucky Thomas G. Barnes, Extension Wildlife Specialist Bernice U. Constantin, USDA-APHIS-ADC ome birds come into conflict with man as a S consequence of their roosting, feeding, and nesting activities. House or English sparrows (Passer domesticus), European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris), pigeons (Columba livia), blackbirds, and woodpeckers are examples of this conflict. Other species, such as geese, vultures, and House sparrow Red-winged blackbird raptors, are not considered pests but can cause problems or become a nuisance. Sparrows, starlings, and pigeons frequently roost or nest on rafters, window sills, and ledges. Blackbirds — including red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus), common grackles (Quiscalus quiscula), starlings, and brown- headed cowbirds (Molothrus ater) — often estab- Cowbird Common grackle lish large winter and summer roosts which can create a nuisance or health hazard in urban The purpose of this publication is to provide areas. The constant tapping and hole-building information about the control of roost problems activities of woodpeckers during the reproductive caused by urban pigeons, starlings, house spar- season can frustrate homeowners. rows, and small urban birds. Individuals who Birds can cause other problems, including the experience problems with woodpeckers should occasional cardinal or Northern mockingbird that ask the local county Extension office for a copy of slams into a window during spring time and the publication FOR-39, Controlling Woodpecker other birds that create a nuisance around a Damage. -

The Synanthropic Status of Wild Rock Doves (Columba Livia) and Their Contribution to Feral Pigeon Populations

Rivista Italiana di Ornitologia - Research in Ornithology, 90 (1): 51-56, 2020 DOI: 10.4081/rio.2020.479 The synanthropic status of wild rock doves (Columba livia) and their contribution to feral pigeon populations Natale Emilio Baldaccini Abstract - Wild rock doves still breed in suitable habitats along Parole chiave: colombo selvatico, colombo di città, Columba southern and insular Italy, even if their colonies are threatened by livia, uccelli sinatropici. the genetic intrusion of feral pigeons. One of their prominent behav- iours is the daily foraging flights from colonial to feeding grounds which involves coming into contact with man-made buildings. These are exploited firstly as roosting places near crop resources and later INTRODUCTION for nesting. This incipient synanthropy is not extended to direct food Feral pigeons are among those birds with the most de- dependence on humans, by which they tend to remain independent. In the same way that ferals genetically intruded the wild colonies, in veloped degree of synanthropy, being one of the oldest urban habitats, rock doves mix with ferals because of the large inter- and most common human commensal worldwide (Lever, breeding possibilities. In the natural range of the wild species, this has 1987). Nevertheless, a synanthropic status may also cha- occurred since the appearance of the feral form of pigeons and still racterize another pigeon, namely the wild rock dove (Co- continues with the residual populations of rock doves, representing lumba livia Gmelin, 1789), the ancestors of domestic pige- their endless contribution to the feral populations, at least until the dis- solution of the gene pool of the primordial form of wild rock dove. -

The Pigeon Names Columba Livia, ‘C

Thomas M. Donegan 14 Bull. B.O.C. 2016 136(1) The pigeon names Columba livia, ‘C. domestica’ and C. oenas and their type specimens by Thomas M. Donegan Received 16 March 2015 Summary.—The name Columba domestica Linnaeus, 1758, is senior to Columba livia J. F. Gmelin, 1789, but both names apply to the same biological species, Rock Dove or Feral Pigeon, which is widely known as C. livia. The type series of livia is mixed, including specimens of Stock Dove C. oenas, wild Rock Dove, various domestic pigeon breeds and two other pigeon species that are not congeners. In the absence of a plate unambiguously depicting a wild bird being cited in the original description, a neotype for livia is designated based on a Fair Isle (Scotland) specimen. The name domestica is based on specimens of the ‘runt’ breed, originally illustrated by Aldrovandi (1600) and copied by Willughby (1678) and a female domestic specimen studied but not illustrated by the latter. The name C. oenas Linnaeus, 1758, is also based on a mixed series, including at least one Feral Pigeon. The individual illustrated in one of Aldrovandi’s (1600) oenas plates is designated as a lectotype, type locality Bologna, Italy. The names Columba gutturosa Linnaeus, 1758, and Columba cucullata Linnaeus, 1758, cannot be suppressed given their limited usage. The issue of priority between livia and domestica, and between both of them and gutturosa and cucullata, requires ICZN attention. Other names introduced by Linnaeus (1758) or Gmelin (1789) based on domestic breeds are considered invalid, subject to implicit first reviser actions or nomina oblita with respect to livia and domestica. -

Emission Scenarios for Biocides Used As Avicides (EUBEES, 2003)

SUPPLEMENT TO THE METHODOLOGY FOR RISK EVALUATION OF BIOCIDES EMISSION SCENARIO DOCUMENT FOR BIOCIDES USED AS AVICIDES (PRODUCT TYPE 15) Mathieu Rolland, Pascal Deschamps (Cabinet Paracelse) July 2003 This report has been developed ni the context of the EC EUBEES project entitled "Gathering, review and development of environmental emission scenarios for biocides (EUBEES 2). The contents have to be discussed and agreed by the EUBEES 2 working group, consisting of representatives of some Member States, CEFIC and the Commission. The financial support of the French Ministry of ecology and sustainable development is gratefully acknowledged (Ref. BC02000753). Foreword ______________________________________________________________________________ This report gives a description of the emission scenarios for avicides used in the European Community (EC). The scenarios and assessments are dealing with the environment including the non-target mammals and birds. This document describes a method of estimating the emission rates of avicides to the primary receiving environmental compartments (e.g. air, soil, and water). This allows the estimation of a worst case Predicted Environmental Concentration (PEC) for each compartment. The calculation of a realistic worst case PEC using environmental interactions is considered to be fate and behaviour modelling, and is outside the scope of these guidelines. Discussions in the working group for the EC project “Gathering, review and development of environmental emission scenarios for biocides (EUBEES 2)” (Baumann, -

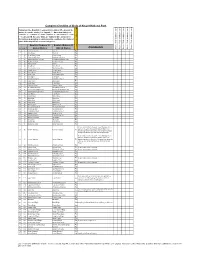

BIRD TRACKS TABLE 1: Bird Food & Habitat Use by Land-Based Birds in South Australia

BIRD TRACKS TABLE 1: Bird Food & Habitat Use by land-based birds in South Australia. Shows where birds look for food, what types of food they find there, how they find and catch it, and the types of birds that tend to use each habitat layer and how they prefer to find their food. Feeding Group Where & how they feed Common Foods Key Features & Species in Group you may see in Schools Birds you see Hunting in the Air – Swooping, Scooping, Sallying & Snatching Look & See Hover up high or perch up Small live animals: Powerful legs, feet, talons, Swoopers high, sight prey and catch it rats, mice, rabbits & for grabbing & holding - Birds of Prey on ground, in air or among other birds. prey. Wings for speed By Day - Eagles, trees. Grab prey in talons, Dead animals or or gliding. Kites, Harriers perch and use hooked beak carrion Nankeen Kestrel, to tear up for eating Black-shouldered Kite, Falcons, Goshawks & Sparrowhawks. Brown Goshawk, Whistling Kite, By night – Owls Wedge-tail Eagle Air Swimming Catch insects in open air by Free flying insects: Long rounded wings for Insect Scoopers scooping them up as fly variety of small speed OR shorter, broader past. Continually in air or moths, flies, bees wings for gliding at speed. By Day - Swallows, making trips out from mosquitoes Martins, Bee-eaters Fairy Martin, perches. etc. Woodswallows. Welcome Swallow, By Night – Nightjars Dusky Woodswallow Frogmouths. Somersaulting Catch insects in open air Free flying insects: Short rounded wings for Insect Snatchers above ground or among variety of small manoeuvrability, long tail can trees & shrubs with ‘sally’ moths, flies, bees be fanned for quick stop or Willy Wagtails, (leap into air off ground or mosquitoes etc balance as turn, whiskers at Fantails, other bird perch, to dive on insect) or Insects on surface: base of beak to guide insects species such as ‘snatch’ insect off surface snatched into mouth. -

Kruger Comprehensive

Complete Checklist of birds of Kruger National Park Status key: R = Resident; S = present in summer; W = present in winter; E = erratic visitor; V = Vagrant; ? - Uncertain status; n = nomadic; c = common; f = fairly common; u = uncommon; r = rare; l = localised. NB. Because birds are highly mobile and prone to fluctuations depending on environmental conditions, the status of some birds may fall into several categories English (Roberts 7) English (Roberts 6) Comments Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps # Rob # Global Names Old SA Names Rough Status of Bird in KNP 1 1 Common Ostrich Ostrich Ru 2 8 Little Grebe Dabchick Ru 3 49 Great White Pelican White Pelican Eu 4 50 Pinkbacked Pelican Pinkbacked Pelican Er 5 55 Whitebreasted Cormorant Whitebreasted Cormorant Ru 6 58 Reed Cormorant Reed Cormorant Rc 7 60 African Darter Darter Rc 8 62 Grey Heron Grey Heron Rc 9 63 Blackheaded Heron Blackheaded Heron Ru 10 64 Goliath Heron Goliath Heron Rf 11 65 Purple Heron Purple Heron Ru 12 66 Great Egret Great White Egret Rc 13 67 Little Egret Little Egret Rf 14 68 Yellowbilled Egret Yellowbilled Egret Er 15 69 Black Heron Black Egret Er 16 71 Cattle Egret Cattle Egret Ru 17 72 Squacco Heron Squacco Heron Ru 18 74 Greenbacked Heron Greenbacked Heron Rc 19 76 Blackcrowned Night-Heron Blackcrowned Night Heron Ru 20 77 Whitebacked Night-Heron Whitebacked Night Heron Ru 21 78 Little Bittern Little Bittern Eu 22 79 Dwarf Bittern Dwarf Bittern Sr 23 81 Hamerkop