Canberra Bird Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecology of Feral Pigeons: Population Monitoring, Resource Selection, and Management Practices Erin E

Chapter Ecology of Feral Pigeons: Population Monitoring, Resource Selection, and Management Practices Erin E. Stukenholtz, Tirhas A. Hailu, Sean Childers, Charles Leatherwood, Lonnie Evans, Don Roulain, Dale Townsley, Marty Treider, R. Neal Platt II, David A. Ray, John C. Zak and Richard D. Stevens Abstract Feral pigeons (Columba livia) are typically ignored by ornithologists but can be found roosting in the thousands within cities across the world. Pigeons have been known to spread zoonoses, through ectoparasites and excrement they produce. Along with disease, feral pigeons have an economic impact due to the cost of cleanup and maintenance of human infrastructure. Many organizations have tried to decrease pigeon abundances through euthanasia or use of chemicals that decrease reproductive output. However, killing pigeons has been unsuccessful in decreasing abundance, and chemical inhibition can be expensive and must be used throughout the year. A case study at Texas Tech University has found that populations fluctu- ate throughout the year, making it difficult to manage numbers. To successfully decrease populations, it is important to have a multifaceted approach that includes removing necessary resources (i. e. nest sites and roosting areas) and decreasing the number of offspring through humane techniques. Keywords: birth control, nest sites, nuisance, rock doves, zoonoses 1. Introduction Of the 7.53 billion people that live on Earth, over half inhabit cities [1, 2]. Increase in development has altered biodiversity through an increase in fragmenta- tion and invasive species abundance. Urban areas are highly susceptible to invasions of nonnative species [3], which can increase threat to native species and increase economic costs due to environmental and structural damage [4, 5]. -

Management of Racing Pigeons

37_Racing Pigeons.qxd 8/24/2005 9:46 AM Page 849 CHAPTER 37 Management of Racing Pigeons JAN HOOIMEIJER, DVM Open flock management, which is used in racing pigeon medicine, assumes the individual pigeon is less impor- tant than the flock as a whole, even if that individual is monetarily very valuable. The goal when dealing with rac- ing pigeons is to create an overall healthy flock com- posed of viable individuals. This maximizes performance and profit. Under ideal circumstances, problems are pre- vented and infectious diseases are controlled. In contrast, poultry and (parrot) aviculture medicine is based on the principles of the closed flock concept. With this concept, prevention of disease relies on testing, vaccinating and a strict quarantine protocol — measures that are not inte- gral to racing pigeon management. This difference is due to the very nature of the sport of pigeon racing; contact among different pigeon lofts (pigeon houses) constantly occurs. Every week during the racing season, pigeons travel — confined with thou- sands of other pigeons in special trucks — to the release site. Pigeons from different lofts are put together in bas- kets. Confused pigeons frequently enter a strange loft. In addition, training birds may come into contact with wild birds during daily flight sessions. Thus, there is no way to prevent exposure to contagious diseases within the pop- ulation or to maintain a closed flock. The pigeon fancier also must be aware that once a disease is symptomatic, the contagious peak has often already occurred, so pre- ventive treatment is too late. Treatment at this point may be limited to minimizing morbidity and mortality. -

INTRODUCED CORELLA ISSUES PAPER April 2014

INTRODUCED CORELLA ISSUES PAPER April 2014 City of Bunbury Page 1 of 35 Disclaimer: This document has been published by the City of Bunbury. Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this document is made in good faith and on the basis that the City of Bunbury, its employees and agents are not liable for any damage or loss whatsoever which may occur as a result of action taken or not taken, as the case may be, in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to herein. Information pertaining to this document may be subject to change, and should be checked against any modifications or amendments subsequent to the document’s publication. Acknowledgements: The City of Bunbury thanks the following stakeholders for providing information during the drafting of this paper: Mark Blythman – Department of Parks and Wildlife Clinton Charles – Feral Pest Services Pia Courtis – Department of Parks and Wildlife (WA - Bunbury Branch Office) Carl Grondal – City of Mandurah Grant MacKinnon – City of Swan Peter Mawson – Perth Zoo Samantha Pickering – Shire of Harvey Andrew Reeves – Department of Agriculture and Food (WA) Bill Rutherford – Ornithological Technical Services Publication Details: Published by the City of Bunbury. Copyright © the City of Bunbury 2013. Recommended Citation: Strang, M., Bennett, T., Deeley, B., Barton, J. and Klunzinger, M. (2014). Introduced Corella Issues Paper. City of Bunbury: Bunbury, Western Australia. Edition Details: Title: Introduced Corella Issues Paper Production Date: 15 July 2013 Author: M. Strang, T. Bennett Editor: M. Strang, B. Deeley Modifications List: Version Date Amendments Prepared by Final Draft 15 July 2013 M. -

Wonder Bag Depth 16" Handle 18" No

AVIARY WEST fiird Neb No. AW-36 Diameter 11" Bag Depth 16" Handle 36" No. AW-18 Diameter 11" Wonder Bag Depth 16" Handle 18" No. AW-12 8" Win~8 ~~~mDe:;~h 11" i Handle 12" ~ by Weldell Phillips Call or write us~If' Playa del Rey, California forinformati;n.priCin~g.~...~~~~~~iir Our nets feature 100% ~~~if/.r:n,tlJ nylon netting, hardwood handles, and spring steel hoops. 3018 LA PLATA AVENUE HACIENDA HEIGHTS, CA 91745 Since the beginning of time, man's de In World War I homing pigeons were (213) 330-8700 sire to control his own destiny has been used when other forms of communication responsible for many ingenious methods were impossible to establish. The 77th of long distance communication. Division, famed 'Lost Battallion of Tireless marathon runners, throbbing Argonne,' was saved from total de drums and intricate smoke signals indicate struction by Cher Ami, last of the sticken :/A the age-old desperate human desire for group's seven homers. The doomed men rapidly received news. The Pharaohs of were being unintentionally pounded to Sunshine Egypt relied on the swiftest of dependable pieces by their own artillery. In despera creatures, the homing pigeon, whose abil tion, Cher Ami was released into the i'ish and Rtr ity to unerringly fly hundreds of miles to metal-strewn sky. Although grieviously their homes, helped them build a highly wounded in flight, the valiant bird finally eompany cultured civilization. fluttered down to the roof of his home loft SPECIALIZING IN The earliest record of homing pigeons, at Rampont. -

Belgian Winners We Make the Difference

TESTED AND APPROVED BY SUCCESSFUL PIGEON FANCIERS. 2021 - ENG ® OROVET WINNERS With Belgian Winners we make the difference. Thomas Lataire CEO Group Lataire bv Belgian Winners stands for Belgian top quality. The success with pigeons depends on a combina 1 n the product ion department of Orovet bv, a tion of factors: the experience of the fancier, the subsidiary of Groupe Lataire bv, high quality quality of the pigeons, the loft and the nutritional health products for racing pigeons are produced support. With the nutritional system of Belgian and developed. Winners, we make the difference. Precisely because the quality, the type of raw material and its application makes the differen ce, we have surrounded ourselves with a nutriti on expert from the sports world, a pigeon vet, a nutrition engineer and an experience expert. The "pigeon sport" evolves just as in all other sports. The "type" athlete and his guidance from the past, wouldn't even carne to work today. Why? Because in all branches of sport, the bar is being raised more and more. Every pigeon fancier has his own opinion and in terpretation concerning the use of supplements. But it's a good thing too. Ambachtenlaan 3-5 9880 Aalter Belgium group History in animal feed sales since 1947 Lata1re animal healthcare The Lataire family is ready for the third generati on as a trader in ani mal feed. 1 n 194 7 Gerard Lataire started a company in grains and feed in Beernem (Belgium) and served the farmers in the region with the brands Remy (Wijgmaal), Vanhove (Ledeberg), Buysse (1 ngelmunster), Talpe (Kortrijk) and Debaillie (Roeselare). -

INVESTING in CANBERRA Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension to Moncrieff Group Centre ($24M)

AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY Gungahlin Central Canberra New Works New Works Ÿ Environmental Offsets – Gungahlin (EPIC) ($0.462m). Ÿ Australia Forum – Investment ready ($1.5m). Ÿ Gungahlin Joint Emergency Services Centre – Future use study ($0.450m). Ÿ Canberra Theatre Centre Upgrades – Stage 2 ($1.850m). Ÿ Throsby – Access road and western intersection ($5.3m). Ÿ City Plan Implementation ($0.150m). BUDGET Ÿ William Slim/Barton Highway Roundabout Signalisation ($10.0m). Ÿ City to the Lake Arterial Roads Concept Design ($2.750m). Ÿ Corroboree Park – Ainslie Park Upgrade ($0.175m). TAYLOR JACKA Work in Progress Ÿ Dickson Group Centre Intersections – Upgrade ($3.380m). Ÿ Ÿ Disability Access Improvements – Reid CIT ($0.260m). 2014-15 Franklin – Community Recreation Irrigated Park Enhancement ($0.5m). BONNER Ÿ Gungahlin – The Valley Ponds and Stormwater Harvesting Scheme ($6.5m). Ÿ Emergency Services Agency Fairbairn – Incident management upgrades ($0.424m). MONCRIEFF Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension from Burrumarra Avenue to Mirrabei Drive ($11.5m). Ÿ Fyshwick Depot – Underground fuel storage tanks removal and site remediation ($1.5m). INVESTING IN CANBERRA Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension to Moncrieff Group Centre ($24m). Ÿ Lyneham Sports Precinct – Stage 4 tennis facility enhancement ($3m). Ÿ Horse Park Drive Water Quality Control Pond ($6m). Ÿ Majura Parkway to Majura Road – Link road construction ($9.856m). Ÿ Kenny – Floodways, Road Access and Basins (Design) ($0.5m). CASEY AMAROO FORDE Ÿ Narrabundah Ball Park Stage 2 – Design ($0.5m). HALL Ÿ Ÿ Throsby – Access Road (Design) ($1m). HALL New ACT Courts. INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS NGUNNAWAL Work in Progress Ÿ Ainslie Music Hub ($1.5m). Belconnen Ÿ Barry Drive – Bridge Strengthening on Commercial Routes ($0.957m). -

Cockatiels Free

FREE COCKATIELS PDF Thomas Haupt,Julie Rach Mancini | 96 pages | 05 Aug 2008 | Barron's Educational Series Inc.,U.S. | 9780764138966 | English | Hauppauge, United States How to Take Care of a Cockatiel (with Pictures) - wikiHow A cockatiel is a popular choice for a pet bird. It is a small parrot with a variety of color patterns and a head crest. They are attractive as well as friendly. They are capable of mimicking speech, although they can be difficult to understand. These birds are good at whistling and you can teach them to sing along to tunes. Life Expectancy: 15 to 20 years with proper care, and sometimes as Cockatiels as 30 years though this is rare. In their native Australia, cockatiels are Cockatiels quarrions or weiros. They primarily live in the Cockatiels, a region of the northern part of the Cockatiels. Discovered inthey are the smallest members of the cockatoo family. They exhibit many of the Cockatiels features and habits as the larger Cockatiels. In the wild, they live in large flocks. Cockatiels became Cockatiels as pets during the s. They are easy to breed in captivity and their docile, friendly personalities make them a natural fit for Cockatiels life. These birds can Cockatiels longer be trapped and exported from Australia. These little birds are gentle, affectionate, and often like to be petted and held. Cockatiels are not necessarily fond of cuddling. They simply want to be near you and will be very happy to see you. Cockatiels are generally friendly; however, an untamed bird might nip. You can prevent bad Cockatiels at an early age Cockatiels ignoring bad behavior as these birds aim to please. -

Canberra Bird Notes

canberra ISSN 0314-8211 bird Volume 43 Number 2 July 2018 notes Registered by Australia Post 100001304 CANBERRA ORNITHOLOGISTS GROUP, INC. PO Box 301 Civic Square ACT 2608 2017-18 Committee President Neil Hermes 0413 828 045 Vice-President Steve Read 0408 170 915 Secretary Bill Graham 0466 874 723 Treasurer Vacant 6231 0147 (h) Member Jenny Bounds Member Sue Lashko Member Lia Battisson Member David McDonald Member Paul Fennell Member A.O. (Nick) Nicholls Member Prue Watters Email Contacts General inquiries [email protected] President [email protected] Canberra Bird Notes [email protected]/[email protected] COG Database Inquiries [email protected] COG Membership [email protected] COG Web Discussion List [email protected] Conservation [email protected] Gang-gang Newsletter [email protected] GBS Coordinator [email protected] Publications for sale [email protected] Unusual bird reports [email protected] Website [email protected] Woodland Project [email protected] Other COG contacts Conservation Jenny Bounds Field Trips Sue Lashko 6251 4485 (h) COG Membership Sandra Henderson 6231 0303 (h) Canberra Bird Notes Editor Michael Lenz 6249 1109 (h) Assistant Editor Kevin Windle 6286 8014 (h) Editor for Annual Bird Report Paul Fennell 6254 1804 (h) Newsletter Editor Sue Lashko, Gail Neumann (SL) 6251 4485 (h) Databases Jaron Bailey 0439 270 835 (a.h.) Garden Bird Survey Duncan McCaskill 6259 1843 (h) Rarities Panel Barbara Allan 6254 6520 (h) Talks Program Organiser Jack Holland 6288 7840 (h) Records Officer Nicki Taws 6251 0303 (h) Website Julian Robinson 6239 6226 (h) Sales Kathy Walter 6241 7639 (h) Waterbird Survey Michael Lenz 6249 1109 (h) Distribution of COG publications Dianne Davey 6254 6324 (h) COG Library Barbara Allan 6254 6520 (h) Use the General Inquiries email to arrange access to library items or for general enquiries, or contact the Secretary on 0466 874 723. -

Attack by a Peregrine Falcon on a Little Eagle on November 25, 1979

AUSTRALIAN 238 \ ARNEY: Peregrine Falcon BIRD WATCHER Attack by a Peregrine Falcon on a Little Eagle On November 25, 1979 whilst inspecting Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus eyries at Nowingi, Victoria, in company with Brian Smith, we witnessed an attack by a pair of Peregrines on a Little Eagle Hieraaetus morphnoides. At the time I was participating in the Victorian Fisheries and Wildlife Department's Peregrine Project. Almost immediately after the Little Eagle was disturbed from its perch in a Belar Casuarina cristata it was pursued by the Falcon, closely fol lowed by her mate. Both birds made several passes at the Little Eagle, the Falcon pulling out when within two metres of its prey, and the Tiercel when approximately five metres from it. In the final attack the Falcon actually struck the Little Eagle behind the head, dislodging a few small feathers and causing it to plummet into a wheat crop some 7-10 metres below. Although we made a diligent search for 20 minutes we failed to locate the victim, but to our utter amazement it then rose from the crop in an endeavour to reach the cover of trees about 150 metres distant succeeding just in time to avoid another onslaught by the Falcon. Over the past four years there has been a close associatiOn between these birds, the Peregrines breeding in the nest occupied by the Little Eagles the previous season. At the time of this incident the Peregrine chicks were fledged and witnessed the encounter from a nearby vantage point. It is significant that the incident took place in the vicinity of the nest in which the Little Eagle had recently reared its young, for when I passed it again on August 17, 1980 the Tiercel was indulging in court ship behaviour in the presence of the Falcon perched in the particular nest tree, thus indicating a continuity of the pattern over the previous four years. -

Ecology of Feral Pigeon (Columba Livia) in Urban Areas of Rawalpindi/ Islamabad, Pakistan

Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 45(5), pp. 1229-1234, 2013 Ecology of Feral Pigeon (Columba livia) in Urban Areas of Rawalpindi/ Islamabad, Pakistan Sakhawat Ali,*1 Bushra Allah Rakha,1 Iftikhar Hussain,1 Muhammad Sajid Nadeem2 and Muhammad Rafique3 1Department of Wildlife Management, Pir Mehr Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi-46300, Pakistan 2Department of Zoology, Pir Mehr Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi-46300, Pakistan 3Zoological Division, Pakistan Museum of Natural History, Islamabad, Pakistan Abstract.- This study was designed to study the ecology of feral pigeon (Columba livia) in the urban areas of Rawalpindi/Islamabad, Pakistan. Seasonal changes in population density, sex ratio, age group, roosting sites, nesting sites, food and water points of pigeons were recorded in Rawalpindi/Islamabad. Higher population density of the pigeon in Islamabad was recorded in winter season followed by autumn, spring and summer season (0.13, 0.13, 0.10 and 0.09 individuals/ha respectively) whereas the higher population density of the pigeon in Rawalpindi was found in summer season followed by winter, spring and autumn (0.13, 0.11, 0.11 and 0.10 individuals/ha, respectively). The male and female sex ratio of the pigeon population confirms 1:1 sex ratio, both in Rawalpindi/Islamabad in different seasons. However, adult and juvenile numbers in the pigeon population did not follow 1:1 ratio; adults were more than juveniles in Rawalpindi/Islamabad in all seasons. The roosting sites, nesting sites, food and water points did differ in different seasons in Islamabad. Highest population of the pigeon was recorded in old buildings (0.30 individual/ha) and lowest in parklands (0.008 individual/ha). -

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT TIPS for Dealing with BIRD PESTS

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT TIPS for dealing with BIRD PESTS Lynn Braband, NYSIPM Program of Cornell University As a culture, we have always valued wildlife. Despite that, many animals have been hunted or culled in such a manner as to decimate populations. The goal of wildlife management is, according to Dan Decker of Cornell University, “ . to maximize the benefits of wildlife while minimizing the costs of wildlife. Points to consider when dealing with wildlife are: Is there a problem that is significant enough to make action necessary? Do you know the laws concerning management of this particular animal? Have you considered health and safety aspects? Is the pest animal causing health or safety concerns to people or facilities? Will the ensuing management treatment cause any health or safety concern? Are the proposed treatments humane? While we don’t object to most treatments of insect pests, the management of vertebrate wildlife pests objectionable? Is the treatment effective? What information did you find to support your choice of management treatment? Is the treatment practical? Is the cost worth the result? Is it sustainable in time and cost needed? How would the management treatment be viewed by outsiders? “Act as if you are being videotaped.” What regulatory agencies have a say in wildlife management? The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is the regulatory agency dealing with bird management. The NYS DEC regulates wildlife management and has ECO (Environmental Conservation Officers) in the field. The NYS DEC is also the final say on Registered products (pesticides) including products not always considered ‘pesticides’ such as reproductive inhibitors. -

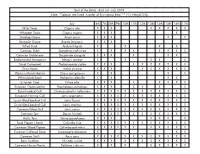

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X