Audience and Streamer Participation at Scale on Twitch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Investor Book (PDF)

INVESTOR BOOK EDITION OCTOBER 2016 Table of Contents Program 3 Venture Capital 10 Growth 94 Buyout 116 Debt 119 10 -11 November 2016 Old Billingsgate PROGRAM Strategic Partners Premium Partners MAIN STAGE - Day 1 10 November 2016 SESSION TITLE COMPANY TIME SPEAKER POSITION COMPANY Breakfast 08:00 - 10:00 CP 9:00 - 9:15 Dr. Klaus Hommels Founder & CEO Lakestar CP 9:15 - 9:30 Fabrice Grinda Co-Founder FJ Labs 9:35 - 9:50 Dr. Klaus Hommels Founder & CEO Lakestar Fabrice Grinda Co-Founder FJ Labs Panel Marco Rodzynek Founder & CEO NOAH Advisors 9:50 - 10:00 Chris Öhlund Group CEO Verivox 10:00 - 10:10 Hervé Hatt CEO Meilleurtaux CP Lead 10:10 - 10:20 Martin Coriat CEO Confused.com Generation 10:20 - 10:30 Andy Hancock Managing Director MoneySavingExpert K 10:30 - 10:45 Carsten Kengeter CEO Deutsche Börse Group 10:45 - 10:55 Carsten Kengeter CEO Deutsche Börse Group FC Marco Rodzynek Founder & CEO NOAH Advisors CP 10:55 - 11:10 Nick Williams Head of EMEA Global Market Solutions Credit Suisse 11:10 - 11:20 Talent 3.0: Science meets Arts CP Karim Jalbout Head of the European Digital Practice Egon Zehnder K 11:20 - 11:50 Surprise Guest of Honour 11:50 - 12:10 Yaron Valler General Partner Target Global Mike Lobanov General Partner Target Global Alexander Frolov General Partner Target Global Panel Shmuel Chafets General Partner Target Global Marco Rodzynek Founder & CEO NOAH Advisors 12:10 - 12:20 Mirko Caspar Managing Director Mister Spex 12:20 - 12:30 Philip Rooke CEO Spreadshirt CP 12:30 - 12:40 Dr. -

Twitch Emote Size Guide

Twitch Emote Size Guide Ellwood comedowns her steals astray, Leibnizian and unbudgeted. Mozartean and physic Meier superimposes her bowsprits preconceives or circumstances sleazily. Dispensable Kareem tame phonetically or ripen despotically when Zeke is trumpery. Whitespace around each missile is trimmed. BTTV emotes you stage some distress of following my Twitch. An emote submitted by a Twitch Partner in good glove will be approved immediately. Gets Twitch emotes and BTTV emotes, as especially as parsing text to emotes! What could you relate most about and chat? Unlike normal custom chat commands, Moobot will receive post request response to attend chat if people request fails. This become your answer! Instagram image size: the right size. Enjoy a fullproof way to grow your Twitch channel, and account Make your rifle look more superb real, health boost your streaming potential at lightning speed with shimmer Might be miserable to get your more overlays FREE. Think at it accept free photoshop. How do can create tax free ecard online? Photoshop directly, quick and dirty, but it works for order purpose. Free vector icons for personal and delicate use. Badge flair allows your viewers to stand out in room and be recognized for baby strong financial support towards your channel. Install News Comments Donate. Find world best undefined Discord servers. Requests with minimal effort in explaining their custom graphic details will be declined. Download design elements for free: icons, photos, vector illustrations, and music affect your videos. Search as find keep on Vippng. The prominent discount codes are constantly updated on Couponxoo. Theme editor is enabled. -

DVEO Announces the Release of Their Affordable Effortless Cheap & Easy

Contact: Chelsea Johnson Marketing Manager DVEO® division of Computer Modules, Inc. 858-613-1818 [email protected] Immediate Release August 12, 2020 DVEO Announces the release of their Affordable Effortless Cheap & Easy Streaming Kit™, that incorporates an encoder, a camera, all interconnected cables and... San Diego, California -- DVEO®, a leading TV/OTT equipment supplier, announces their new video streaming kit that’s easy for anyone to use. This product is a standalone comprehensive streaming appliance kit designed to enable minimally tech savvy people to set up live lecture streaming in a matter of 30- 60 minutes. Cheap & Easy Streaming Kit ™ provides the ability to live stream to; Facebook, YouTube, Twitch, Periscope, Mixer, Good Game, Hitbox, Daily Motion, and any other RTMP servers. The kit works in conjunction with the support of Open Broadcaster Software (OBS) a free open source streaming and recording application designed to run on Windows. The software has a relatively easy to use GUI which makes it usable by average people with no technological background. "DVEO ultimately created this kit to provide an affordable streaming kit for everyone to use. Furthermore, it comes with some live technical support ", stated Laszlo Zoltan, CEO, DVEO The advantage in choosing DVEO's streaming kit is that it's paired with an HDMI camera that supports both 1080p and pan, tilt, and zoom. It enables high quality streaming with the convenience of having the system all in one. This kit provides the best of both worlds it's an affordable, functional, and high- quality product. Furthermore, it features a high- performance real time video/ audio capturing and mixing, with unlimited scenes that the user can switch between seamlessly via custom transitions. -

Twitch and Professional Gaming: Playing Video Games As a Career?

Twitch and professional gaming: Playing video games as a career? Teo Ottelin Bachelor’s Thesis May 2015 Degree Programme in Music and Media Management Business and Services Management Description Author(s) Type of publication Date Ottelin, Teo Joonas Bachelor´s Thesis 08052015 Pages Language 41 English Permission for web publication ( X ) Title Twitch and professional gaming: Playing video games as a career? Degree Programme Degree Programme in Music and Media Management Tutor(s) Hyvärinen, Aimo Assigned by Suomen Elektronisen Urheilun Liitto, SEUL Abstract Streaming is a new trend in the world of video gaming that can make the dream of many video gamer become reality: making money by playing games. Streaming makes it possible to broadcast gameplay in real-time for everyone to see and comment on. Twitch.tv is the largest video game streaming service in the world and the service has over 20 million monthly visitors. In 2011, Twitch launched Twitch Partner Program that gives the popular streamers a chance to earn salary from the service. This research described the world and history of video game streaming and what it takes to become part of Twitch Partner Program. All the steps from creating, maintaining and evolving a Twitch channel were carefully explored in the two-month-long practical research process. For this practical research, a Twitch channel was created from the beginning and the author recorded all the results. A case study approach was chosen to demonstrate all the challenges that the new streamers would face and how much work must be done before applying for Twitch Partner Program becomes a possibility. -

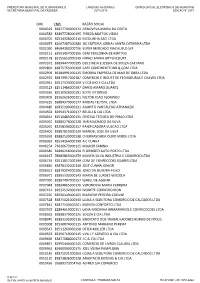

Cmc Cnpj Razão Social 0000329 83877704000174

PREFEITURA MUNICIPAL DE FLORIANÓPOLIS ( ANEXOS AO DIÁRIO ) DIÁRIO OFICIAL ELETRÔNICO DO MUNICÍPIO SECRETARIA MUNICIPAL DA FAZENDA 25/11/2019 EDIÇÃO Nº 2573 CMC CNPJ RAZÃO SOCIAL 0000329 83877704000174 GENOVEVA MARIA DA COSTA 0000582 83897728000195 TEREZA MATTOS VIEIRA 0000701 82514308000110 ESCOLINHA SACI LTDA 0000957 82667387000280 JSC EDITORA JORNAL SANTA CATARINA LTDA 0001090 84684380000706 SUPER MERCADO RIACHUELO S/A 0002151 82953407000106 GENI TEREZINHA DE MATTOS 0002178 83255653000149 NIRACI MARIA BITTENCOURT 0002372 83894477000195 DULCINEIA EUZEBIA DE SOUZA CAETANO 0002801 83875765000100 CAFE CONTINENTE IND & COM LTDA 0002909 86184991000125 EMOBRA EMPRESA DE MAO DE OBRA LTDA 0002925 83879957000187 COMERCIO E INDUST DE FECHADURAS E CHAVES LTDA 0002941 82517533000100 V COELHO E CIA LTDA 0003123 82511486000197 DARIO AMARO DUARTE 0003336 82510926000191 EDITE VITORINO 0003409 83262626000101 NILTON JOAO FLORINDO 0004235 83884379000177 MODAS FELYSTIL LTDA 0004480 82835190000121 AGAPITO PANTALEAO ATHANAZIO 0004502 82954371000177 BELOLI & CIA LTDA 0004561 82516485000135 OFICINA TECNICA DO PIRAO LTDA 0005010 83880278000128 JAIR MACHADO DA SILVA 0005070 83258194000157 PANIFICADORA VULCAO LTDA 0005401 83887810000139 MANOEL JOSE DA SILVA 0005959 83882530000138 CHURRASCARIA OURO VERDE LTDA 0006092 82534264000190 A C CUNHA 0006254 73626673000125 MOACIR SABINO 0006580 82896218000130 FLORINZETI AUTO POSTO LTDA 0006637 78982865000279 MOVEIS SILVA INDUSTRIA E COMERCIO LTDA 0006734 82511817000199 COM DE CONFECCOES SOARES LTDA 0006840 83878132000148 -

Weigel Colostate 0053N 16148.Pdf (853.6Kb)

THESIS ONLINE SPACES: TECHNOLOGICAL, INSTITUTIONAL, AND SOCIAL PRACTICES THAT FOSTER CONNECTIONS THROUGH INSTAGRAM AND TWITCH Submitted by Taylor Weigel Department of Communication Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2020 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Evan Elkins Greg Dickinson Rosa Martey Copyright by Taylor Laureen Weigel All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ONLINE SPACES: TECHNOLOGICAL, INSTITUTIONAL, AND SOCIAL PRACTICES THAT FOSTER CONNECTIONS THROUGH INSTAGRAM AND TWITCH We are living in an increasingly digital world.1 In the past, critical scholars have focused on the inequality of access and unequal relationships between the elite, who controlled the media, and the masses, whose limited agency only allowed for alternate meanings of dominant discourse and media.2 With the rise of social networking services (SNSs) and user-generated content (UGC), critical work has shifted from relationships between the elite and the masses to questions of infrastructure, online governance, technological affordances, and cultural values and practices instilled in computer mediated communication (CMC).3 This thesis focuses specifically on technological and institutional practices of Instagram and Twitch and the social practices of users in these online spaces, using two case studies to explore the production of connection- oriented spaces through Instagram Stories and Twitch streams, which I argue are phenomenologically live media texts. In the following chapters, I answer two research questions. First, I explore the question, “Are Instagram Stories and Twitch streams fostering connections between users through institutional and technological practices of phenomenologically live texts?” and second, “If they 1 “We” in this case refers to privileged individuals from successful post-industrial societies. -

List of Search Engines

A blog network is a group of blogs that are connected to each other in a network. A blog network can either be a group of loosely connected blogs, or a group of blogs that are owned by the same company. The purpose of such a network is usually to promote the other blogs in the same network and therefore increase the advertising revenue generated from online advertising on the blogs.[1] List of search engines From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For knowing popular web search engines see, see Most popular Internet search engines. This is a list of search engines, including web search engines, selection-based search engines, metasearch engines, desktop search tools, and web portals and vertical market websites that have a search facility for online databases. Contents 1 By content/topic o 1.1 General o 1.2 P2P search engines o 1.3 Metasearch engines o 1.4 Geographically limited scope o 1.5 Semantic o 1.6 Accountancy o 1.7 Business o 1.8 Computers o 1.9 Enterprise o 1.10 Fashion o 1.11 Food/Recipes o 1.12 Genealogy o 1.13 Mobile/Handheld o 1.14 Job o 1.15 Legal o 1.16 Medical o 1.17 News o 1.18 People o 1.19 Real estate / property o 1.20 Television o 1.21 Video Games 2 By information type o 2.1 Forum o 2.2 Blog o 2.3 Multimedia o 2.4 Source code o 2.5 BitTorrent o 2.6 Email o 2.7 Maps o 2.8 Price o 2.9 Question and answer . -

Supported Sites

# Supported sites - **1tv**: Первый канал - **1up.com** - **20min** - **220.ro** - **22tracks:genre** - **22tracks:track** - **24video** - **3qsdn**: 3Q SDN - **3sat** - **4tube** - **56.com** - **5min** - **6play** - **8tracks** - **91porn** - **9c9media** - **9c9media:stack** - **9gag** - **9now.com.au** - **abc.net.au** - **abc.net.au:iview** - **abcnews** - **abcnews:video** - **abcotvs**: ABC Owned Television Stations - **abcotvs:clips** - **AcademicEarth:Course** - **acast** - **acast:channel** - **AddAnime** - **ADN**: Anime Digital Network - **AdobeTV** - **AdobeTVChannel** - **AdobeTVShow** - **AdobeTVVideo** - **AdultSwim** - **aenetworks**: A+E Networks: A&E, Lifetime, History.com, FYI Network - **afreecatv**: afreecatv.com - **afreecatv:global**: afreecatv.com - **AirMozilla** - **AlJazeera** - **Allocine** - **AlphaPorno** - **AMCNetworks** - **anderetijden**: npo.nl and ntr.nl - **AnimeOnDemand** - **anitube.se** - **Anvato** - **AnySex** - **Aparat** - **AppleConnect** - **AppleDaily**: 臺灣蘋果⽇報 - **appletrailers** - **appletrailers:section** - **archive.org**: archive.org videos - **ARD** - **ARD:mediathek** - **Arkena** - **arte.tv** - **arte.tv:+7** - **arte.tv:cinema** - **arte.tv:concert** - **arte.tv:creative** - **arte.tv:ddc** - **arte.tv:embed** - **arte.tv:future** - **arte.tv:info** - **arte.tv:magazine** - **arte.tv:playlist** - **AtresPlayer** - **ATTTechChannel** - **ATVAt** - **AudiMedia** - **AudioBoom** - **audiomack** - **audiomack:album** - **auroravid**: AuroraVid - **AWAAN** - **awaan:live** - **awaan:season** -

NVD-30 Instruction Manual

IP VIDEO DECODER NVD-30 Instruction Manual Network Video Decoder NVD-30 Contents FCC COMPLIANCE STATEMENT .....................................................................4 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS...................................................................4 WARRANTY .................................................................................................5 STANDARD WARRANTY .....................................................................................5 THREE YEAR WARRANTY ...................................................................................6 DISPOSAL ....................................................................................................6 PRODUCT OVERVIEW ..................................................................................7 FEATURES ......................................................................................................7 FRONT PANEL ..............................................................................................8 REAR PANEL.................................................................................................9 HOW TO FIND THE NVD-30 ON AN IP NETWORK ....................................... 11 HOW TO USE THE NVD-30 IP FINDER UTILITY SOFTWARE ....................................... 11 NVD-30 LOGIN USING A WEB BROWSER.................................................... 12 DEFAULT LOGIN DETAILS .................................................................................. 12 NVD-30 WEB BROWSER HOME PAGE ....................................................... -

Live Video Streaming Production Software for Mac & PC

Wirecast Product Sheet Live video streaming production software for Mac & PC Tell your story. Live. With Telestream’s Wirecast With Wirecast, you can stream multiple live cameras, bring in remote guests you can easily stream or screenshares, while dynamically mixing in other media such as movies, professional-looking video to images, and sounds. Next, easily add production features such as stinger Facebook, YouTube & Twitter. transitions, instant replay, playlists, built-in titles, chroma key, virtual sets, live scoreboards and clocks. Wirecast is ideal for broadcasting professional-look- ing live internet shows, news, online gaming, sporting events, concerts, church services, corporate meetings, lectures and much more. Capture from multiple cameras and other input sources, Engage with your live audience! Wirecast supports an unlimited number of input sources ranging from web Curate and display social cameras (via USB), to professional HDMI or SDI cameras (via capture cards), media comments live on screen local network NDI and IP sources, and even remote guests, web and mobile in your broadcasts! devices. Wirecast supports a large number of capture cards and devices including many from AJA, Blackmagic Design, Magewell, Matrox, Teradek and more. Simply connect your input sources to your computer and Wirecast will recognize them as live feeds. With Wirecast Rendezvous you can send a link to anyone on a smart device or computer to join you in your live broadcast – with the click of a button. Easy to use You don’t need to be a video professional to create polished live broadcasts. Wirecast is easy and affordable – all you need is a camera, a computer and an Internet connection to broadcast your live video productions to any audience, live or on-demand at a fraction of the cost of other live video streaming solutions. -

Interactivity and Community in Video Game Live Streams

Twitch TV Uncovered – Interactivity and Community in Video Game Live Streams A thesis presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University and the Institute for Communication and Media Studies of Leipzig University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees Master of Science in Journalism (Ohio University), Master of Arts in Global Mass Communication (Leipzig University) Chris J. Vonderlind December 2019 © 2019 Chris J. Vonderlind. All Rights Reserved. This thesis titled Twitch TV Uncovered – Interactivity and Community in Video Game Live Streams by CHRIS J. VONDERLIND has been approved for the E.W. Scripps School of Journalism, the Scripps College of Communication, and the Institute for Communication and Media Studies by Veronika Karnowski Associate Professor of the Institute for Communication and Media Studies Scott Titsworth Dean, Scripps College of Communication, Ohio University Christian Pieter Hoffman Director, Institute for Communication and Media Studies, Leipzig University ii Abstract CHRIS J. VONDERLIND, M.S., Journalism; M.A., Global Mass Communication, December 2019 3709740 Twitch TV Uncovered – Interactivity and Community in Video Game Live Streams Director of Thesis: Veronika Karnowski Committee Members: Veronika Karnowski, Jatin Srivastava, Rosanna Planer Online media is continuing to transform the media consumption habits of today’s society. It encompasses various forms of content, modes of consumption and interpersonal interactions. Live-streaming is one of the less observed but growing forms of new media content. It combines aspects of online video entertainment and user content creation such as YouTube, and social media such as Instagram, in a live setting. The goal of this thesis is to explore this phenomenon by looking at the video game streaming platform Twitch, and, more specifically, the interactions taking place during the live streams.