Drones in Hybrid Warfare: Lessons from Current Battlefields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Child Soldiers Continue to Be Deployed to Libya

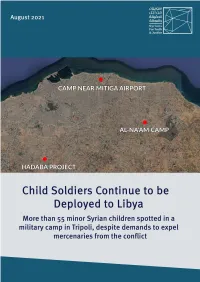

www.stj-sy.org Child Soldiers Continue to be Deployed to Libya More than 55 minor Syrian children spotted in a military camp in Tripoli, despite demands to expel mercenaries from the conflict Page | 2 www.stj-sy.org Despite an October 2020 ceasefire agreement and repeated international calls to expel all foreign forces and mercenaries from the Libyan conflict, recruitment operations continue to enlist and transfer Syrian mercenaries into Libya – including children under the age of 18. In 2021, the recruitments have largely been carried out by Russia and Turkey. In July 2021, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) obtained new testimonies on the deployment of new groups of children to Tripoli, Libya’s capital, since March 2021. Notably, we heard from a 16-year-old child soldier, a fighter in the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division, and a medical worker who treated a number of recruited children in a hospital in Tripoli. We contacted sources via phone and through encrypted online applications. Sources confirmed the spread of 55 new Syrian child recruits in areas overseen by the Government of National Accord (GNA), including makeshift camp near Mitiga International Airport, al-Sahbah camp, Hadaba project and al-Na’am camp. Image 1 – A map of locations where Syrian child soldiers have been observed in Libya. Military Groups Recruiting Children Sources provided STJ with the names of military groups formed by the opposition-Syrian National Army (SNA) who are confirmed to have children serving among their ranks in Libya. The groups include the Auxiliary Forces/al-Quwat al-Radifa, Front and Alert Units, and Special Intrusion Units. -

Efes 2018 Combined Joint Live Fire Exercise

VOLUME 12 ISSUE 82 YEAR 2018 ISSN 1306 5998 A LOOK AT THE TURKISH DEFENSE INDUSTRY LAND PLATFORMS/SYSTEMS SECTOR EFES 2018 COMBINED JOINT LIVE FIRE EXERCISE PAKISTAN TO PROCURE 30 T129 ATAK HELICOPTER FROM TURKEY TURAF’S FIRST F-35A MAKES MAIDEN FLIGHT TURKISH DEFENCE & AEROSPACE INDUSTRIES 2017 PERFORMANCE REPORT ISSUE 82/2018 1 DEFENCE TURKEY VOLUME: 12 ISSUE: 82 YEAR: 2018 ISSN 1306 5998 Publisher Hatice Ayşe EVERS Publisher & Editor in Chief Ayşe EVERS 6 [email protected] Managing Editor Cem AKALIN [email protected] Editor İbrahim SÜNNETÇİ [email protected] Administrative Coordinator Yeşim BİLGİNOĞLU YÖRÜK [email protected] International Relations Director Şebnem AKALIN [email protected] Advertisement Director 30 Yasemin BOLAT YILDIZ [email protected] Translation Tanyel AKMAN [email protected] Editing Mona Melleberg YÜKSELTÜRK Robert EVERS Graphics & Design Gülsemin BOLAT Görkem ELMAS [email protected] Photographer Sinan Niyazi KUTSAL 46 Advisory Board (R) Major General Fahir ALTAN (R) Navy Captain Zafer BETONER Prof Dr. Nafiz ALEMDAROĞLU Cem KOÇ Asst. Prof. Dr. Altan ÖZKİL Kaya YAZGAN Ali KALIPÇI Zeynep KAREL DEFENCE TURKEY Administrative Office DT Medya LTD.STI Güneypark Kümeevleri (Sinpaş Altınoran) Kule 3 No:142 Çankaya Ankara / Turkey 58 Tel: +90 (312) 447 1320 [email protected] www.defenceturkey.com Printing Demir Ofis Kırtasiye Perpa Ticaret Merkezi B Blok Kat:8 No:936 Şişli / İstanbul Tel: +90 212 222 26 36 [email protected] www.demirofiskirtasiye.com Basım Tarihi Nisan - Mayıs 2018 Yayın Türü Süreli DT Medya LTD. ŞTİ. 74 © All rights reserved. -

LUH Clears 6 Kms Altitude Flight

www.aeromag.in n January - February 2019 | Vol 13 | Issue 1 LUH Clears 6 KMs Altitude Flight World’s Largest Importer, in association with Yet Indian Armed Forces Society of Indian Aerospace Technologies & Industries Need to be Better Equipped - Page 14 Official Media Partner Feb 20 - 24, 2019. Yelahanka Air Force Station, Bangalore Advertise with AEROMAG Show Dailies 1 Total Air and Missile Defense Sky Capture BARAK 8 - Naval-based BARAK 8 - Land-based ARROW 2 - Anti-Ballistic ARROW 3 - Anti-Ballistic Air & Missile Defense Air & Missile Defense Missile Defense Missile Defense Full Spectrum of Integrated, Networked Meet us at AERO INDIA 2019 Air and Missile Defense Solutions to Defeat Hall B: B2.1, B2.2 Threats at Any Range and Altitude IAI offers a comprehensive range of Air and Missile Defense Systems for land and naval applications. From VSHORAD to long-range, to theater and exo-atmospheric systems against ballistic missiles. Our unique solutions, based on lessons derived from vast operational experience, incorporate state-of-the-art technology and full networking for the most effective System of Systems. The result: IAI’s solutions. www.iai.co.il • [email protected] 2 Total Air and Missile Defense Advertise with Official Show Dailies of AEROMAG AEROMAG OFFICIAL MEDIA PARTNER Sky Capture BARAK 8 - Naval-based BARAK 8 - Land-based ARROW 2 - Anti-Ballistic ARROW 3 - Anti-Ballistic Air & Missile Defense Air & Missile Defense Missile Defense Missile Defense Full Spectrum of Integrated, Networked Meet us at AERO INDIA 2019 AERO INDIA 2019 Air and Missile Defense Solutions to Defeat Hall B: B2.1, B2.2 Threats at Any Range and Altitude 20-24 FEBRUARY, BENGALURU IAI offers a comprehensive range of Air and Missile Defense Systems for land and naval applications. -

Syrian Armed Opposition Powerbrokers

March 2016 Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS Cover: A rebel fighter of the Southern Front of the Free Syrian Army gestures while standing with his fellow fighter near their weapons at the front line in the north-west countryside of Deraa March 3, 2015. Syrian government forces have taken control of villages in southern Syria, state media said on Saturday, part of a campaign they started this month against insurgents posing one of the biggest remaining threats to Damascus. Picture taken March 3, 2015. REUTERS/Stringer All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2016 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2016 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jennifer Cafarella is the Evans Hanson Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War where she focuses on the Syrian Civil War and opposition groups. Her research focuses particularly on the al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al Nusra and their military capabilities, modes of governance, and long-term strategic vision. She is the author of Likely Courses of Action in the Syrian Civil War: June-December 2015, and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria: An Islamic Emirate for al-Qaeda. -

Country Travel Risk Summaries

COUNTRY RISK SUMMARIES Powered by FocusPoint International, Inc. Report for Week Ending September 19, 2021 Latest Updates: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, India, Israel, Mali, Mexico, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine and Yemen. ▪ Afghanistan: On September 14, thousands held a protest in Kandahar during afternoon hours local time to denounce a Taliban decision to evict residents in Firqa area. No further details were immediately available. ▪ Burkina Faso: On September 13, at least four people were killed and several others ijured after suspected Islamist militants ambushed a gendarme patrol escorting mining workers between Sakoani and Matiacoali in Est Region. Several gendarmes were missing following the attack. ▪ Cameroon: On September 14, at least seven soldiers were killed in clashes with separatist fighters in kikaikelaki, Northwest region. Another two soldiers were killed in an ambush in Chounghi on September 11. ▪ India: On September 16, at least six people were killed, including one each in Kendrapara and Subarnapur districts, and around 20,522 others evacuated, while 7,500 houses were damaged across Odisha state over the last three days, due to floods triggered by heavy rainfall. Disaster teams were sent to Balasore, Bhadrak and Kendrapara districts. Further floods were expected along the Mahanadi River and its tributaries. ▪ Israel: On September 13, at least two people were injured after being stabbed near Jerusalem Central Bus Station during afternoon hours local time. No further details were immediately available, but the assailant was shot dead by security forces. ▪ Mali: On September 13, at least five government soldiers and three Islamist militants were killed in clashes near Manidje in Kolongo commune, Macina cercle, Segou region, during morning hours local time. -

Saudi Arabia 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Riyadh

Saudi Arabia 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Riyadh This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Embassy in Riyadh. OSAC encourages travelers to use this report to gain baseline knowledge of security conditions in Saudi Arabia. For more in-depth information, review OSAC’s Saudi Arabia country page for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private- sector representatives with an OSAC password. Travel Advisory The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses Saudi Arabia at Level 2, indicating travelers should exercise increased caution due to terrorism and the threat of missile and drone attacks on civilian targets. Do not travel to within 50 miles of the border with Yemen due to terrorism and armed conflict. Review OSAC’s report, Understanding the Consular Travel Advisory System. Overall Crime and Safety Situation Crime Threats The U.S. Department of State has assessed Riyadh as being a LOW-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government interests. Crime in Saudi Arabia has increased over recent years but remains at levels far below most major metropolitan areas in the United States. Criminal activity does not typically target foreigners and is mostly drug-related. Review OSAC’s reports, All That You Should Leave Behind, The Overseas Traveler’s Guide to ATM Skimmers & Fraud, Taking Credit, Hotels: The Inns and Outs, and Considerations for Hotel Security. Cybersecurity Issues The Saudi government continues to expand its cybersecurity activities. -

Creating a Competitive Environment for Defense Aerospace in a Protectionist Multipolar World: a Study of India and Israel

Beyond: Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 4 Article 1 Creating a Competitive Environment for Defense Aerospace in a Protectionist Multipolar World: A Study of India and Israel Shlok Misra Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, [email protected] Tanish Jain University of California San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/beyond Part of the Technology and Innovation Commons Recommended Citation Misra, Shlok and Jain, Tanish () "Creating a Competitive Environment for Defense Aerospace in a Protectionist Multipolar World: A Study of India and Israel," Beyond: Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://commons.erau.edu/beyond/vol4/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Beyond: Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Creating a Competitive Environment for Defense Aerospace in a Protectionist Multipolar World: A Study of India and Israel Cover Page Footnote Shlok Misra is an undergraduate at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Daytona Beach. He is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Science in Aeronautical Science, with a minor in Airline Operations and Business Administration. Shlok is passionate about using technology for enhancing airspace efficiency and safety. Shlok’s research also focuses on studying human factors to enhance aviation safety. Shlok is currently a Commercial Pilot with an instrument rating. Tanish Jain is an undergraduate at the University of California, San Diego. He is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering, with a focus on Machine Learning and Controls. -

WEEKLY REPORT 21 – 28 May 2021

WEEKLY REPORT 21 – 28 May 2021 KEY DYNAMICS Presidential elections .................................................................................................... 2 Assad elected for 4th term .......................................................................... 2 IDPs stranded ................................................................................................................. 3 Um Batna families deported ....................................................................... 3 Self-Administration, ISIS concerns ............................................................................ 4 ISIS continue to attack .................................................................................. 4 MERCY CORPS HUMANITARIAN ACCESS WEEKLY REPORT, 21 – 28 May 2021 1 Presidential elections Voter turnout low, contrary to government media reports Assad elected for 4th term Despite pro-government media claiming that Bashar al-Assad has been re-elected president of voter turnout was high, reports from local Syria in a landslide victory, in which he officially sources directly contradict this. Election centers received 95.1% of the votes. The result, although in Syrian government areas were largely empty ultimately unsurprising due to both the lack of save for a few where pro-government citizens viable opposition candidates and expected and Baath party members gathered in front of fraudulency of the elections themselves, did not cameras to welcome government officials going come without disruptions. to vote. Voters were for -

UAS – Low Hanging Fruit India Still to Pluck

01/21 UAS – Low Hanging Fruit India Still to Pluck Air Marshal Anil Chopra PVSM AVSM VM VSM (Retd) Director General, CAPS 22 April 2021 Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) began making unmanned aerial system (UAS) with the Fluffy target drone in 1970s, which was replaced by the reusable, subsonic, pilotless target aircraft Lakshya that first flew in 1985. Around 30 were produced and operated by all the services. The advanced version Lakshya-II was flight-tested in January 2012. In March 2017, Air Force version of Lakshya-II was flight tested. The Army-centric Nishant is a multi-mission UAS with day/night capability for battlefield surveillance and targeting, and was first flown in August 1996. DRDO claimed it equivalent of IAI’s Searcher. Finally only four were built. A wheeled version of the Nishant UAS, named “Panchi” is known to be under development. There are a large number of DRDO UAS projects since 1985, but what really counts is, what gets inducted into the Armed Forces. That number after nearly 45 years should have been much higher. DRDO’s Rustom Series Rustom-1 was evolved from Burt Rutan’s Long-EZ with 250 km range, for visual and radar surveillance. It was to be a tactical UAV with endurance of 12 hours, and made its first flight in November 2009. Rustom-H, is a larger UAV was with flight endurance of over 24 hours. TAPAS-BH- 201 (Rustom-2) Medium Altitude Long Endurance (MALE) UAV has been derived from the National Aerospace Laboratories (NAL) LCRA (Light Canard Research Aircraft), and is meant to supplement the Heron UAVs in service. -

OSAC Country Security Report Saudi Arabia

OSAC Country Security Report Saudi Arabia Last Updated: August 10, 2021 Travel Advisory The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication indicates travelers should not travel due to COVID-19. The advisory further highlights that travelers should reconsider travel due to the threat of missile and drone attacks on civilian facilities. Exercise increased caution due to terrorism. Do not travel to within 50 miles of the Yemeni border, including Abha, Jizan, Najran, Khamis Mushait, and the Abha airport due to missile and drone attacks; and terrorism. In addition, do not travel to Qatif in the Eastern Province and its suburbs, including Awamiyah due to terrorism. Review OSAC’s report, Understanding the Consular Travel Advisory System. The Institute for Economics & Peace Global Peace Index 2021 ranks Saudi Arabia 125 out of 163 worldwide, rating the country as being at a Low state of peace. Crime Environment The U.S. Department of State has assessed Riyadh as being a LOW-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government interests. The U.S. Department of State has not included a Crime “C” Indicator on the Travel Advisory for Saudi Arabia. Emergency contact information differs in regions and cities. In the Riyadh and Makkah regions, call 911 police and fire department/civil defense. Elsewhere in Saudi Arabia, call 999 for police and 998 for the fire department/civil defense. Review the State Department’s Crime Victims Assistance brochure. Crime: General Threat Crime in Saudi Arabia has increased over recent years, but remains at levels far below most major metropolitan areas in the United States. -

The Turkey-UAE Race to the Bottom in Libya: a Prelude to Escalation

The Turkey-UAE race to the bottom in Libya: a prelude to escalation Recherches & Documents N°8/2020 Aude Thomas Research fellow, Fondation pour la recherche stratégique July 2020 www.frstrategie.org SOMMAIRE THE TURKEY-UAE RACE TO THE BOTTOM IN LIBYA: A PRELUDE TO ESCALATION ................................. 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 1. TURKEY: EXERCISING THE FULL MILITARY CAPABILITIES SPECTRUM IN LIBYA ............................. 3 2. THE UAE’S MILITARY VENTURE IN LIBYA ................................................................................ 11 2.1. The UAE’s failed campaign against Tripoli ....................................................... 11 2.2. Russia’s support to LNA forces: from the shadow to the limelight ................ 15 CONCLUSION: LOOKING AT FUTURE NATIONAL DYNAMICS IN LIBYA ................................................... 16 FONDATION pour la RECHERCHE STRATÉ GIQUE The Turkey-UAE race to the bottom in Libya: a prelude to escalation This paper was completed on July 15, 2020 Introduction In March, the health authorities in western Libya announced the first official case of Covid- 19 in the country. While the world was enforcing a lockdown to prevent the spread of the virus, war-torn Libya renewed with heavy fighting in the capital. Despite the UNSMIL’s1 call for a lull in the fighting, the Libyan National Army (LNA) and its allies conducted shelling on Tripoli, targeting indistinctly residential neighbourhoods, hospitals and armed groups’ locations. The Government of National Accord (GNA) answered LNA’s shelling campaign by launching an offensive against several western cities. These operations could not have been executed without the support of both conflicting parties’ main backers: Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The protracted conflict results from both the competing parties’ unwillingness to agree on conditions to resume political negotiations2. -

Security, Protracted Conflicts and the Role of Drones in Eurasia Note: the Term ‘Drone’ Is Used Interchangeably with ‘Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)’ in This Report

On the Edge Security, protracted conflicts and the role of drones in Eurasia Note: The term ‘drone’ is used interchangeably with ‘Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)’ in this report. Supported by a funding from the Foundation Open Society Institute in cooperation with the Human Rights Initiative of the Open Society Foundations. Drone Wars UK is a small British NGO established in 2010 to undertake research and advocacy around the use of armed drones. We believe that the growing use of remotely-controlled, armed unmanned systems is encouraging and enabling a lowering of the threshold for the use of lethal force as well as eroding well established human rights norms. While some argue that the technology itself is neutral, we believe that drones are a danger to global peace and security. We have seen over the past decade that once these systems are in the armoury, the temptation to use them becomes great, even beyond the constraints of international law. As more countries develop or acquire this technology, the danger to global peace and security grows. Published by Drone Wars UK Drone Wars UK Written by Joanna Frew Peace House, 19 Paradise Street January 2021 Oxford, OX1 1LD Design by Chris Woodward www.dronewars.net www.chriswoodwarddesign.co.uk [email protected] On the Edge | 1 Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Ukraine and conflicts with Russian-backed separatists in Crimea and Donbas 5 Use of Drones in Crimea & the Donbas Armed Drones on the Horizon Russian and Separatist use of Drones Ukrainian Drones Russian and Separatists Drones 3 Georgia, South