Nartanam 17-1 Final.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Godrej Consumer Products Limited

GODREJ CONSUMER PRODUCTS LIMITED List of shareholders in respect of whom dividend for the last seven consective years remains unpaid/unclaimed The Unclaimed Dividend amounts below for each shareholder is the sum of all Unclaimed Dividends for the period Nov 2009 to May 2016 of the respective shareholder. The equity shares held by each shareholder is as on Nov 11, 2016 Sr.No Folio Name of the Shareholder Address Number of Equity Total Dividend Amount shares due for remaining unclaimed (Rs.) transfer to IEPF 1 0024910 ROOP KISHORE SHAKERVA I R CONSTRUCTION CO LTD P O BOX # 3766 DAMMAM SAUDI ARABIA 180 6,120.00 2 0025470 JANAKIRAMA RAMAMURTHY KASSEMDARWISHFAKROO & SONS PO BOX 3898 DOHA QATAR 240 8,160.00 3 0025472 NARESH KUMAR MAHAJAN 176 HIGHLAND MEADOW CIRCLE COPPELL TEXAS U S A 240 8,160.00 4 0025645 KAPUR CHAND GUPTA C/O PT SOUTH PAC IFIC VISCOSE PB 11 PURWAKARTA WEST JAWA INDONESIA 360 12,240.00 5 0025925 JAGDISHCHANDRA SHUKLA C/O GEN ELECTRONICS & TDG CO PO BOX 4092 RUWI SULTANATE OF OMAN 240 8,160.00 6 0027324 HARISH KUMAR ARORA 24 STONEMOUNT TRAIL BRAMPTON ONTARIO CANADA L6R OR1 360 12,240.00 7 0028652 SANJAY VARNE SSB TOYOTA DIVI PO BOX 6168 RUWI AUDIT DEPT MUSCAT S OF OMAN 60 2,040.00 8 0028930 MOHAMMED HUSSAIN P A LEBANESE DAIRY COMPANY POST BOX NO 1079 AJMAN U A E 120 4,080.00 9 K006217 K C SAMUEL P O BOX 1956 AL JUBAIL 31951 KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA 180 6,120.00 10 0001965 NIRMAL KUMAR JAIN DEP OF REVENUE [INCOMETAX] OFFICE OF THE TAX RECOVERY OFFICER 4 15/295A VAIBHAV 120 4,080.00 BHAWAN CIVIL LINES KANPUR 11 0005572 PRAVEEN -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Name of the Artist & Contact Details Links Grading

MINISTRY OF CULTURE FESTIVAL OF INDIA CELL PANEL OF ARTISTS/GROUPS FOR PARTICIPATION IN FESTIVALS OF INDIA ABROAD (O - OUTSTANDING, P- PROMISING, W- WAITING) Kathak S.NO Name of the Artist & contact Details Links Grading 1. Arijeet Mukherjee Business Development and Events Coordinator https://vimeo.com/151495589 Aditi Mangaldas Dance Company - The Drishtikon Dance Foundation Password: within123 O ADD: N-75/4/2, Sainik Farms South Lane - W 17 (Main) New Delhi-110080 MOB: 0 93111 57771 | 0 98105 66044 http://vimeo.com/aditimangaldasdance/ WEB: www.aditimangaldasdance.com Email: unchartedseas [email protected] Password: AMDC-US 2 Shovana Narayan IA&AS retd https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hha O Kathak Guru(Padmashri& central Sangeet Natak Akademi awardee) Mq0Nxg5s T2-LL-103, Commonwealth Games Village, Delhi-110092 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eOD Cell:+919811173734+919810725340 RnwLc9Mg Email:[email protected] or [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KAw Padmashree Awardee (1996) jM9ggTh8 SNA Awardee (1999-2000) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsUd IJI0yn8 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aR W89rFJ6dc https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KAw jM9ggTh8 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UN A_4Cf1taQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Ax MxNkuxvw https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RhL 6wQ1Y-WA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7A3 dh8pBElg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Xe RJqb65e4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjsl5 Rq3HVo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJQ pWVKMTJI https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjsl5 Rq3HVo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Uf sLeqIYhY https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o- ftl8rIjnc https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jrnt MQy2320 https://i.ytimg.com/vi/IMKCvbQ7cUk/mq default.jpg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MS wixkNxubg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oO1 -WsLotZg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gZrd 14SjJkA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJq PTQTD-Zs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PG5 -DTTykdk https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VW Fuv9mBUQI https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1UY NfMqZ9aQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDq xUHbTLHw 3. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

President's Report

Vol. 57 No 47 June xx25 - June xx,30, 2016 President’s Report t feels like just yesterday that a group resounding success and will continue to of Rotarians took to their feet at my make a lasting impact on Bombay. The Installation to surprise everyone and Animal Committee was another active new shake things up with their flash mob initiative, working with the animal hospital Irendition of “Happy”. in Parel and with Welfare for Stray Dogs. And a happy year it has been. I have been We acted on our decision to be exacting on the recipient of so much affection and membership rules and unfortunately had to amazing support that this job has been a ask for the resignations of four members. wonderful experience. This past year 7 of our senior members passed away .We added a total of 12 new Preparations for the year began with an members; all of whom we hope will make April retreat in Pune with the Board of promising results. Our Talwada projects great contributions to the Club, resulting Directors, where much of the setting of have struggled with lack of water from in a total Club strength of 314. We have priorities and planning for the year was April onwards for the past few years; this actually seen a lowering of the average mapped out. This was an experiment — year, the deepening of the well and the age of our club.we started the year at an the first of its kind — but it was such a building of a new pipeline will ensure that average 58.9 and end it at 56.9. -

A History of Indian Music by the Same Author

68253 > OUP 880 5-8-74 10,000 . OSMANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Call No.' poa U Accession No. Author'P OU H Title H; This bookok should bHeturned on or befoAbefoifc the marked * ^^k^t' below, nfro . ] A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC BY THE SAME AUTHOR On Music : 1. Historical Development of Indian Music (Awarded the Rabindra Prize in 1960). 2. Bharatiya Sangiter Itihasa (Sanglta O Samskriti), Vols. I & II. (Awarded the Stisir Memorial Prize In 1958). 3. Raga O Rupa (Melody and Form), Vols. I & II. 4. Dhrupada-mala (with Notations). 5. Sangite Rabindranath. 6. Sangita-sarasamgraha by Ghanashyama Narahari (edited). 7. Historical Study of Indian Music ( ....in the press). On Philosophy : 1. Philosophy of Progress and Perfection. (A Comparative Study) 2. Philosophy of the World and the Absolute. 3. Abhedananda-darshana. 4. Tirtharenu. Other Books : 1. Mana O Manusha. 2. Sri Durga (An Iconographical Study). 3. Christ the Saviour. u PQ O o VM o Si < |o l "" c 13 o U 'ij 15 1 I "S S 4-> > >-J 3 'C (J o I A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC' b SWAMI PRAJNANANANDA VOLUME ONE ( Ancient Period ) RAMAKRISHNA VEDANTA MATH CALCUTTA : INDIA. Published by Swaxni Adytaanda Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta-6. First Published in May, 1963 All Rights Reserved by Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta. Printed by Benoy Ratan Sinha at Bharati Printing Works, 141, Vivekananda Road, Calcutta-6. Plates printed by Messrs. Bengal Autotype Co. Private Ltd. Cornwallis Street, Calcutta. DEDICATED TO SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND HIS SPIRITUAL BROTHER SWAMI ABHEDANANDA PREFACE Before attempting to write an elaborate history of Indian Music, I had a mind to write a concise one for the students. -

CURRENT AFFAIRS of February 2019

8 CURRENT AFFAIRS OF FEBRUARY 2018 Defence • The place in Maharashtra where the Indian Army conducted its annual artillery fire power exercise Topchi – Deolali • The five-day multinational maritime exercise conducted at Karachi, Pakistan with participation of 46 countries and slogan "Together for Peace" – Aman-19 • The multinational training exercise held from 27 Jan to 06 Feb 19 in the Western Indian Ocean with participation from USA, India, Netherlands and several East African countries was named – CUTLASS EXPRESS – 19 Persons • The former Chairman of Railway Board who has been appointed as the Chairman and Managing Director of Air India – Shri Ashwani Lohani • The new Chairman of CBDT appointed to replace Shri Sushil Chandra who has taken over as Election Commissioner – Shri Pramod Kumar Mody • The American economist who has been nominated by the US President to be the next World Bank President – David Malpass • The new Director of Central Bureau of Investigation, replacing Shri Alok Verma for a period of two years - Shri Rishi Kumar Shukla Places • The place in Haryana where setting up All India Institute of Medical Sciences was approved by the Union Cabinet – Manethi (Rewari Dist) • The places in Madhya Pradesh and Assam where National Institute of Design were inaugurated through video conferencing in New Delhi – Bhopal and Jorhat • The venue of first ever Drone Olympics, a competition for UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) held from 18 to 21 February 2019 – Bengaluru • The emirate of UAE which has declared Hindi to be its third official -

Kurukshetra Magazine Summary for April 2021 Issue

NURTURING INDIA’S RICH CULTURAL HERITAGE • India with its glorious past has bequeathed a remarkable variety of monuments and sites spread all across the length and breadth of the country. There are 38 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in India (as of 2021), of which 30 are cultural sites, 7 are natural sites and one mixed site. • Along with these are rich and varied intangible cultural heritage of the country like oral traditions and expressions, craftsmanship etc. Heritage are not just reflectors of the past, but opportunities to generate employment and income in the present and future through heritage tourism. Heritage can Change the Rural Economy • There are various heritage structures with cultural and historical significance in the rural hinterlands lying untapped and unattended. Due to the pandemic, people are now more interested in visiting less- crowded rural India. This creates opportunity for rural areas. • There are traditional step wells which have heritage significance and also can be explored if the water sources can be revived. While attracting tourists, it will also solve the water issue faced by the people in the area. Steps Taken by the Govt. • In budget 2020-21, govt. has proposed five archaeological sites, namely, Rakhigarhi (Haryana), Hastinapur (Uttar Pradesh), Shivsagar (Assam), Dholavira (Gujarat) and Adichanallur (Tamil Nadu) to be developed as iconic sites with on-site Museums. • Rakhigarhi, the site of a pre-Indus Valley Civilisation settlement, dating back to about 6500 BCE village is located in Hisar District in Haryana. • Dholavira, a site of ruins of ancient Harappan city, is located near the Dholavira village in Gujarat. -

Dr. Sandip Kumar Raut* Original Research Paper Music

Original Research Paper Volume - 10 | Issue - 8 | August - 2020 | PRINT ISSN No. 2249 - 555X | DOI : 10.36106/ijar Music THE ROLE OF TABLA IN INDIAN MUSIC Dr. Sandip Kumar Asst.Prof. in Dept.of Tabla, Utkal university of culture, Bhubaneswar. *Corresponding Raut* Author ABSTRACT Tabla is a most popular percussion instrument of India coming under membranophones category .Its versatility in all musical styles has enabled it to become most popular percussion instrument of India. It is used in almost all types of music like classical music, light classical music, light music, folk music, religious music, fusion music and western music. It consists of a pair of hand drums namely Tabla and Bayan comprising of contrasting sizes and Timbers. It has ten syllables which forms different types of rhythmic patterns. Its distinct sound and timber makes it as a main accompanying instrument of Indian music. It possesses a sophisticated tonal beauty which elevated the instrument to an unmatched status in the world of percussion. KEYWORDS : Rhythm, percussion, syllables, Tradition, Music, Veda, Tal Tabla is a most popular percussion instrument of North Indian music. It playing and many times the thickness is depending upon the diameter comes under membranophones category of percussion instrument. of Tabla . The instrument not only produces a wild range of sonorities pleasing to many tastes but also gives the performer a great scope to demonstrate Tabla is the main accompanying instrument of Hindustani music. It has his technical facility and speed. It is most developed tal keeping been used in classical, semi classical, light, folk, Bhajan etc. and also in instrument of Indian music which is used in traditional, classical, semi fusion music. -

Final Senior Fellowship Report

FINAL SENIOR FELLOWSHIP REPORT NAME OF THE FIELD: DANCE AND DANCE MUSIC SUB FIELD: MANIPURI FILE NO : CCRT/SF – 3/106/2015 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TWO VAISHNAVISM INFLUENCED CLASSICAL DANCE FORM, SATRIYA AND MANIPURI, FROM THE NORTH EAST INDIA NAME : REKHA TALUKDAR KALITA VILL – SARPARA. PO – SARPARA. PS- PALASBARI (MIRZA) DIST – KAMRUP (ASSAM) PIN NO _ 781122 MOBILE NO – 9854491051 0 HISTORY OF SATRIYA AND MANIPURI DANCE Satrya Dance: To know the history of Satriya dance firstly we have to mention that it is a unique and completely self creation of the great Guru Mahapurusha Shri Shankardeva. Shri Shankardeva was a polymath, a saint, scholar, great poet, play Wright, social-religious reformer and a figure of importance in cultural and religious history of Assam and India. In the 15th and 16th century, the founder of Nava Vaishnavism Mahapurusha Shri Shankardeva created the beautiful dance form which is used in the act called the Ankiya Bhaona. 1 Today it is recognised as a prime Indian classical dance like the Bharatnatyam, Odishi, and Kathak etc. According to the Natya Shastra, and Abhinaya Darpan it is found that before Shankardeva's time i.e. in the 2nd century BC. Some traditional dances were performed in ancient Assam. Again in the Kalika Purana, which was written in the 11th century, we found that in that time also there were uses of songs, musical instruments and dance along with Mudras of 108 types. Those Mudras are used in the Ojha Pali dance and Satriya dance later as the “Nritya“ and “Nritya hasta”. Besides, we found proof that in the temples of ancient Assam, there were use of “Nati” and “Devadashi Nritya” to please God. -

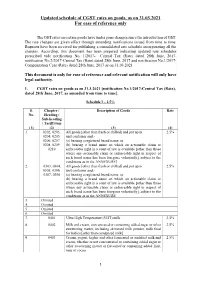

GST Notifications (Rate) / Compensation Cess, Updated As On

Updated schedule of CGST rates on goods, as on 31.03.2021 For ease of reference only The GST rates on certain goods have under gone changes since the introduction of GST. The rate changes are given effect through amending notifications issued from time to time. Requests have been received for publishing a consolidated rate schedule incorporating all the changes. According, this document has been prepared indicating updated rate schedules prescribed vide notification No. 1/2017- Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017, notification No.2/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 and notification No.1/2017- Compensation Cess (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 as on 31.03.2021 This document is only for ease of reference and relevant notification will only have legal authority. 1. CGST rates on goods as on 31.3.2021 [notification No.1/2017-Central Tax (Rate), dated 28th June, 2017, as amended from time to time]. Schedule I – 2.5% S. Chapter / Description of Goods Rate No. Heading / Sub-heading / Tariff item (1) (2) (3) (4) 1. 0202, 0203, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0204, 0205, unit container and,- 0206, 0207, (a) bearing a registered brand name; or 0208, 0209, (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or 0210 enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE] 2. 0303, 0304, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0305, 0306, unit container and,- 0307, 0308 (a) bearing a registered brand name; or (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE 3. -

KRAKAUER-DISSERTATION-2014.Pdf (10.23Mb)

Copyright by Benjamin Samuel Krakauer 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Benjamin Samuel Krakauer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Negotiations of Modernity, Spirituality, and Bengali Identity in Contemporary Bāul-Fakir Music Committee: Stephen Slawek, Supervisor Charles Capwell Kaushik Ghosh Kathryn Hansen Robin Moore Sonia Seeman Negotiations of Modernity, Spirituality, and Bengali Identity in Contemporary Bāul-Fakir Music by Benjamin Samuel Krakauer, B.A.Music; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2014 Dedication This work is dedicated to all of the Bāul-Fakir musicians who were so kind, hospitable, and encouraging to me during my time in West Bengal. Without their friendship and generosity this work would not have been possible. জয় 巁쇁! Acknowledgements I am grateful to many friends, family members, and colleagues for their support, encouragement, and valuable input. Thanks to my parents, Henry and Sarah Krakauer for proofreading my chapter drafts, and for encouraging me to pursue my academic and artistic interests; to Laura Ogburn for her help and suggestions on innumerable proposals, abstracts, and drafts, and for cheering me up during difficult times; to Mark and Ilana Krakauer for being such supportive siblings; to Stephen Slawek for his valuable input and advice throughout my time at UT; to Kathryn Hansen