1 Intertwining Histories in Donald Rodney's Untitled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gallery Guide Is Printed on Recycled Paper

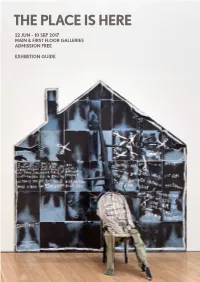

THE PLACE IS HERE 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN & FIRST FLOOR GALLERIES ADMISSION FREE EXHIBITION GUIDE THE PLACE IS HERE LIST OF WORKS 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN GALLERY The starting-point for The Place is Here is the 1980s: For many of the artists, montage allowed for identities, 1. Chila Kumari Burman blends word and image, Sari Red addresses the threat a pivotal decade for British culture and politics. Spanning histories and narratives to be dismantled and reconfigured From The Riot Series, 1982 of violence and abuse Asian women faced in 1980s Britain. painting, sculpture, photography, film and archives, according to new terms. This is visible across a range of Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper Sari Red refers to the blood spilt in this and other racist the exhibition brings together works by 25 artists and works, through what art historian Kobena Mercer has 78 × 190 × 3.5cm attacks as well as the red of the sari, a symbol of intimacy collectives across two venues: the South London Gallery described as ‘formal and aesthetic strategies of hybridity’. between Asian women. Militant Women, 1982 and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. The questions The Place is Here is itself conceived of as a kind of montage: Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper it raises about identity, representation and the purpose of different voices and bodies are assembled to present a 78 × 190 × 3.5cm 4. Gavin Jantjes culture remain vital today. portrait of a period that is not tightly defined, finalised or A South African Colouring Book, 1974–75 pinned down. -

Donald Rodney (1961-1998) Self-Portrait ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ 1990

Donald Rodney (1961-1998) Self-Portrait ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ 1990 Medium: Lightboxes with Duratran prints Size: 5 parts, total, 190.5 x 121.9cm Collection: Arts Council ACC7/1990 1. Art historical terms and concepts Subject Matter Traditionally portraits depicted named individuals for purposes of commemoration and/or propaganda. In the past black figures were rarely portrayed in Western art unless within group portraits where they were often used as a visual and social foil to the main subject. Rodney adopted the portrait to explore issues around black masculine identity - in this case the stereotype of young black men as a ‘public enemy’. The title ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ comes from the writings of cultural theorist Stuart Hall about media representations of young black men as an ‘icon of danger’, a metaphor for all the ills of society. Rodney said of this Art History in Schools CIO | Registered Charity No. 1164651 | www.arthistoryinschools.org.uk work: “I’ve been working for some time on a series…about a black male image, both in the media and black self-perception. I wanted to make a self-portrait [though] I didn’t want to produce a picture with an image of myself in it. It would be far too heroic considering the subject matter. I wanted generic black men, a group of faces that represented in a stereotypical way black man as ‘the other’, a black man as the enemy within the body politic” (1991). Rodney is asking the question: ‘Is this what people see when they see me?’ He has created a kind of ‘everyman’ for every black man, a heterogeneous identity. -

Phillips, M. the Case of the Absent Artist. a Body Of

The Case of the Absent Artist A Body of Evidence of Mike Phillips 1 The Case for the Defence. On the seventeenth of April 1962 Perry Mason, the legendary defence attorney, faced one of his most pataphysical cases. ‘The Case of the Absent Artist’ (CBS 1962) is an account of a transmogrification that resonates through digital arts practice to this day. The author of the popular comic strip ‘Zingy’, Gabe Philips, transforms from a cartoon- ist to a ‘serious’ painter, bifurcating in the process to become Otto Gervaert. This transformation is only completed when he (both Philips and Gervaert) is/are murdered, the artist(s) remains as a body of evi- dence and a body of work. Mason is faced with the absence left by the transformation of the artist; the absent artist (or artists) defines a new space, not emptiness but a place resonant with potential. The following is a re-investigation of this resonant place left by the artist – Philips/Gervaert and how this transformation of the artist is be- ing enacted with increasing frequency. This manifestation of trans- formation, duality and disappearance is symptomatic of a technologi- cal performativity evident in a series of projects and relationships that have informed the development of frameworks, articulated below as ‘Operating Systems’. As forensic tools these Operating Systems are ‘instruments’ or provocative prototypes that enhance our understand- ing of the world and our impact on it. In the case of the absent artist they probe the space that once held the artist to build a new body of evidence. This body of evidence itself builds on an evolutionary thread that has run through the collaborative work of i-DAT.org. -

Re-Recordings | List of Materials ------9 1) Selection of Material from the Recordings Project Archive, Policy 6 Documents and Art Documentation (ACAA)

Re-Recordings | List of Materials --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 1) Selection of material from the Recordings Project Archive, policy 6 documents and art documentation (ACAA) Recordings: a Select Bibliography of Contemporary African, Afro-Caribbean and Asian 5 British Art. London: INiva, 1996. Race, Sex and Class 5. Multi-Ethnic Education in further, Higher and Community Education, 1983 8 Box of Recordings Research Project and Drafts. Chelsea College of Art & Design Library Archive. Anti-Racist Film Programme. London, GLC, March/April 1985. London GLC/ London 3 Against Racism. 1985. The Arts and Ethnic Minorities: Action Plan. London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1986 4 Ward, Liz. St.Martin’s School of Art Library: Collection Development, ILEA Muti-Ethnic 1 Review,Winter/Spring 1985 Chambers, Eddie. Blk Art Group Proposal to Art Colleges, 1983 Black Art in Britain: A bibliography of material held in the Library, Chelsea School of Art, 1986 Asian and Afro-Caribbean British art: a Bibliography of Material Held in the Library, 2 Chelsea College of Art & Design,1989. Art Libraries Journal, The Documentation of Black Artists, v.8, no.4 (Winter 1983) Black Arts in London no.50, 4-17 March 1986 7 African and Asian Visual Artists Archive (Flyer and cards) [Bristol],1990. Arts Council Arts & Ethnic Minorities Action Plan. London, February, 1996 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2) Artists’ multiples, artists’ books, ephemera and video Araeen, Rasheed. The Golden Verses: a Billboard Artwork… Artangel Trust, 1990 Chambers, Eddie. Breaking that Bondage: Plotting that Course. London: Black Art Gallery, 1984 Us and ‘Dem, The Storey Institute , Leicester, 1994. Postcard/Virginia Nimarkoh, 1993. Artist Book. The Image Employed, the use of narrative in Black art. -

Re Imaging Donald Rodney

Re imaging Donald Rodney 1 Introduction Reimaging Donald Rodney explores the work of Black British artist Donald Rodney (1961 – 1998). It is the first UK exhibition to examine Rodney’s digital practice, and through new commissions expands on the potential of Rodney’s archive as a resource for challenging our conceptions of cultural, physical and social identity. Donald Rodney was considered to be He developed his artistic skills during one the most significant artists of his prolonged periods of hospitalisation, generation. Mark Sealy, Director of resulting in him regularly missing Autography ABP stated in an online school, due to his sickle cell condition. interview with TATE Britain for their After taking an arts foundation collection of Rodney’s work; course at Bournville School of Art in Birmingham he went on to Nottingham “[Along] with Donald, Keith Piper, Eddie Trent, where he met Keith Piper and Chambers and people like Sonia Boyce, Eddie Chambers. Chambers and Piper Lubaina Himid. Those characters in my espoused the notion of Black Art/Black view are really quite seminal in terms of Power, which derived largely from beginning to create an articulate voice… the USA through black writers and he was really interested in working with activists like Ron Karenga. Becoming Exhibition new media and new technologies. One a prominent member of the Blk Arts of the great tragedies is that he was Group, RRodney highlighted the Reimaging Donald Rodney aims to The new works developed for the becoming very articulate within this sociopolitical condition of Britain in Donald Rodney, from encapsulate the digital embodiment exhibition include doublethink (2015), space around the end of his career”. -

1 Curriculum Vitae EDDIE CHAMBERS

Curriculum vitae EDDIE CHAMBERS www.eddiechambers.com African Art/African American Art/African Diaspora art history, Field Editor, caa.reviews, (http://www.caareviews.org / http://www.caareviews.org/reviews/2969#.VxlZGaX_R94) appointed August 2014, now serving a second three-year term Member of the editorial board of caa.reviews for a four-year term, from July 1, 2018, to June 30, 2022. Art Monthly Foundation Honorary Patron, (together with Liam Gillick, Hans Haacke, Alfredo Jaar, and Martha Rosler) Appointed June 2018 The University of Texas at Austin Department of Art and Art History 2301 San Jacinto Blvd. Stop D1300 Austin, Texas 78712-1421 EDUCATION Historical and Cultural Studies Department, Goldsmiths College, University of London, (Supervisor, Professor Sarat Maharaj, Internal Examiner, Dr. Carol McKay, External Examiner, Professor Stuart Hall) Black Visual Arts Activity in England 1981-1986: Press and Public Responses, PhD awarded March 31, 1998 Sunderland Polytechnic, Faculty of Art and Design, Fine Art Department, 1980 - 1983. BA (Hons.) Fine Art, 2:1 UT-AUSTIN APPOINTMENT Assistant Professor, Art History, January 2010 – August 2013 Associate Professor, Art History, September 2013 – August 2016 Professor, Art History, September 2016 onwards Inaugural Curatorial Fellow at the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies, Fall Semester 2013/Spring Semester 2014 Assistant Chair, Art History Division, Fall 2015 – Summer 2017, two-year term OTHER TEACHING Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. Visiting Professor, Art History department, spring semester 2008, and spring semester and fall semester 2009. 1 Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. Visiting Professor, Art History department, spring semester and fall semester, 2005 and fall semester 2006. -

Black Art, Black Power: Responses to Soul of a Nation

Black Art, Black Power: Responses to Soul of a Nation Friday 13 October 2017 Starr Cinema, Tate Modern Programme 10.30 Welcome: Richard Martin (Tate) Californian Scenes 10.40 Kellie Jones (Columbia University), ‘South of Pico’ 11.00 Sampada Aranke (School of the Art Institute of Chicago), ‘Death’s Futurity’ 11.20 Discussion, chaired by Zoe Whitley (Tate) 11.50 Break; refreshments in Starr Foyer From Chicago and Washington to Lagos 12.20 Margo Natalie Crawford (University of Pennsylvania), ‘Black Public Interiority, Chicago-Style’ 12.40 Tuliza Fleming (National Museum of African American History and Culture), ‘Jeff Donaldson, FESTAC, and the Washington, D.C., Delegation’ 13.00 Discussion, chaired by Daniel Matlin (King’s College London) 13.30 Lunch New York Photography 14.30 Sherry Turner DeCarava (art historian) and Mark Godfrey (Tate) British Contexts: The Black Arts Movement and Beyond 15.10 Lubaina Himid (artist) and Marlene Smith (artist and curator), chaired by Melanie Keen (Iniva) 16.20 Break; refreshments in Starr Foyer Art in the Age of Black Lives Matter 16.50 Introduction: Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley 17.00 Barby Asante (artist), Kevin Beasley (artist) and Luke Willis Thompson (artist), chaired by Elvira Dyangani Ose (Creative Time and Goldsmiths, University of London) 18.00 Close; reception in Starr Foyer Biographies Sampada Aranke (PhD, Performance Studies) is an Assistant Professor in the Art History, Theory, and Criticism Department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her research interests include performance theories of embodiment, visual culture, and black cultural and aesthetic theory. Her work has been published in e-flux , Artforum , Art Journal , Ecquid Novi: African Journalism Studies , and Trans-Scripts: An Interdisciplinary Online Journal in the Humanities and Social Sciences at UC Irvine. -

Open Call for Creative Proposals

Open Call for Creative Proposals Open Call for proposals for the Birmingham 2022 Cultural Festival: NATURE, TRAMS and BLACK ART 1 BACKGROUND In 2022 we welcome the world to Birmingham and the West Midlands region with a global sporting event like no other, as we host the Birmingham 22 Commonwealth Games. From March to September 2022, a 6-month arts festival will encapsulate and explore the spirit of the Games, and finally give Birmingham its moment in the spotlight. It will reach artists and audiences across the West Midlands region. The festival will aim to double the reach of the sporting events of the Games themselves - engaging at least 2.5million audiences and participants. _______________________________________________________________________________________________ Our vision: To present an ambitious arts festival that will harness a once in a lifetime opportunity to positively disrupt the region’s cultural sector and inspire lasting change. Collaborative and original work by artists and communities will connect people, time and place, as we host the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games. Audacious, playful and inclusive, over 6 months it will entertain, engage and embrace at least 2.5million people, setting Birmingham and the West Midlands in a new creative light. __________________________________________________________________________ Our approach is focused on creativity, collaboration and Commonwealth, always seeking equity in artistic partnerships. Three simple curatorial lines invite and embolden artists to make artworks -

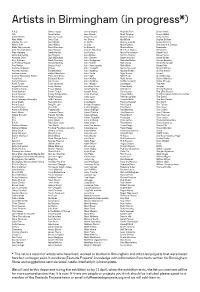

Artists in Birmingham (In Progress*)

Artists in Birmingham (in progress*) A.A.S. Darren Joyce Jenny Moore Michelle Bint Simon Davis A2rt Dave Patten Jess Hands Mick Thacker Simon Webb Adele Prince David A. Hardy Jesse Bruton Mike Holland Sofia Hulten Alan Miller David Cox Jim Byrne Mo White Sophie Bullock Alastair Scruton David Mabb Jo Griffin Mohammed Ali Space Banana Albert Toft David Miller Jo Loki Mona Casey Sparrow and Castice Aleks Wojtulewicz David Prentice Jo Roberts Monica Ross Spectacle Alex Gene Morrison David Rowan Joanne Masding Mrs G. A. Barton Steve Bell Alex Marzeta Derek Horton Joe Hallam Myria Panayiotou Steve Field Alicia Dubnyckyj Des Hughes Joe Welden Nathan Hansen Steve Payne Amanda Grist Dick McGowan John Barrett Nayan Kulkarni Steve Wilkes Amy Kirkham Dinah Prentice John Bridgeman Nicholas Bullen Steven Beasley An Endless Supply Donald Rodney John Butler Nick Jones Stuart Mugridge Ana Rutter Easton Hurd John Hammersley Nick Wells Stuart Tait Andrew Gillespie Ed Lea John Hodgett Nicola Counsell Stuart Whipps Andrew Jackson Ed Wakefield John Newling Nicolas Bullen Su Richardson Andrew Lacon Eddie Chambers John Poole Nigel Amson Surely? Andrew Moscardo Parker Eliza Jane Grose John Salt Nikki Pugh Surjit Simplay Andy Hunt Elizabeth Rowe John Walker Nola James Sylvani Merilion Andy Robinson Elly Clarke John Wallbank OHNE/projects Tadas Stalyga Andy Turner Emily Mulenga John Wigley Ole Hagen Ted Allen Angela Maloney Emily Warner Jonathan Shaw Oliver Braid Temper Angelina Davis Emma Macey Jony Easterby Ollie Smith Tereza Buskova Anna Barham Emma Talbot Joseph -

Keith Piper Special Relationships - Debates About Black Art in America Influenced a Later Generation of Black British Artist’, Apollo, October 2017

H A L E s APOLLO THE INTER NAT IONA L ART MAGAZINE FRANK BOWLING Keith Piper Special Relationships - Debates about black art in America influenced a later generation of black British artist’, Apollo, October 2017 EXHIBITIONS Special relationships Debatesabout black art in America influenceda later generationof black British artists, writes Keith Piper (the focus of a recent displa y, 'The Place is embed their practi ce as a too l of actu al stru g Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age Her e', at the South Londo n Gallery) , Bowling gle, encoding th e politica l ideo logy of th e of Black Power provided a tangible link between two histori Black Panther Party into graphic form for the 12 J uly- 22 October ca l moments. His attenda n ce at t he Fir st Party newspaper from 1967 onwards (Fig. 3). A Tate Modern, London National Black Art Convention, held in Wolver similar set of political alignments informs Dan hampton in 1982, put him int o contact with C. Chandler' s restru cturin g ofF red Hampton's Cata logue by Zoe Whitley and Mark the BLKArt Group, whose membe rs includ ed bullet-ridd led door as a gallery-based assem Godfrey myse lf, Marle ne Smith , Eddie Chambers , blage of fou nd and pa int ed objects . For Betye ISBN 9781849764636 (paperback ), £29 .99 Claudette Johnson, and Dona ld Rodne y, as Saar, assemblage is a crea tive strate gy in her (Tate Publishing) well as young UK-based artists such as Son ia subvers ive remodelling of the mammy figure Boyce, Lubaina Himid , and Rash eedAraeen. -

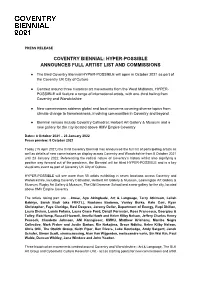

Hyper-Possible Announces Full Artist List and Commissions

PRESS RELEASE COVENTRY BIENNIAL: HYPER-POSSIBLE ANNOUNCES FULL ARTIST LIST AND COMMISSIONS ● The third Coventry Biennial HYPER-POSSIBLE will open in October 2021 as part of the Coventry UK City of Culture ● Centred around three historical art movements from the West Midlands, HYPER- POSSIBLE will feature a range of international artists, with one-third hailing from Coventry and Warwickshire ● New commissions address global and local concerns covering diverse topics from climate change to homelessness, involving communities in Coventry and beyond ● Biennial venues include Coventry Cathedral, Herbert Art Gallery & Museum and a new gallery for the city located above HMV Empire Coventry Dates: 8 October 2021 – 23 January 2022 Press preview: 5 October 2021 Today (15 April 2021) the third Coventry Biennial has announced the full list of participating artists as well as details of new commissions on display across Coventry and Warwickshire from 8 October 2021 until 23 January 2022. Referencing the radical nature of Coventry’s history whilst also signifying a positive way forward out of the pandemic, the Biennial will be titled HYPER-POSSIBLE and is a key visual arts event as part of Coventry UK City of Culture. HYPER-POSSIBLE will see more than 50 artists exhibiting in seven locations across Coventry and Warwickshire, including Coventry Cathedral, Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Leamington Art Gallery & Museum, Rugby Art Gallery & Museum, The Old Grammar School and a new gallery for the city, located above HMV Empire Coventry. The artists taking -

Claudette-Johnson-Exhibition-Notes

Upper Gallery 7. Figure in raw umber, 2018 12. Afterbirth, 1990 Piper Gallery 1. Standing Figure, 2017 Pastels on paper Pastel on paper 16. Reclining Figure, 2017 21. Untitled (with wool and leather), 1982 Acrylic paint, pastel and masking tape on paper Tate: Purchased 2019 Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Pastel and gouache paint on paper Pastel, gouache paint, silver paper, Rugby Art Gallery and Museum Gardens, London Halamish Collection, London leather and wool ‘Although I don’t believe that there is an Courtesy the artist and Hollybush essential truth that artists can convey through This work was included in Johnson’s important 2. Untitled (Yellow Blocks), 2019 1 7. And I Have My Own Business In This Gardens, London representation, I do believe that the fiction of 1992 solo exhibition at The Black-Art Gallery in Pastel and gouache paint on paper Skin, 1982 “blackness” that is the legacy of colonialism Finsbury Park, London, then led by Marlene Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Pastel and gouache paint on paper 22. Standing Figure with African Masks, 2018 can be interrupted by an encounter with the Smith, entitled In This Skin: Drawings by Gardens, London Museums Sheffield Pastel, gouache paint and ground on paper stories that we have to tell about ourselves.’ Claudette Johnson. A young Steve McQueen Tate: Purchased using funds provided by the ‘I wanted to look at how women occupy space. ‘Pushing the pastels around on oversized – Claudette Johnson reviewed the show, describing the works as 2018 Frieze Tate Fund supported by Endeavor I’d made a series of semi-abstract works sheets forces me to build the forms in a ‘overwhelmingly arresting.