Gregory Palamas and Hesychasm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

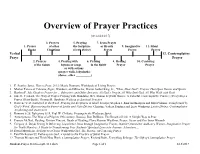

Overview of Prayer Practices

Overview of Prayer Practices (revised 4/2/17) 3. Prayers 5. Praying 7. Jesus Prayer 1. Prayer of other the Scripture or Breath 9. Imaginative 11. Silent Books Christians (lectio divina) Prayer Prayer Prayer Verbal 12. Contemplative Praye Prayer 2. Prayers 4. Praying with 6. Praying 8. Healing 10. Centering of the Saints hymns or songs in the Spirit Prayer Prayer or with actions (prayer walk, labyrinth,) (dance, other __________) 1. E. Stanley Jones, How to Pray, 2015; Maxie Dunnam, Workbook of Living Prayer; 2. Mother Teresa of Calcutta, Signs, Wonders, and Miracles; Martin Luther King, Jr., "Thou, Dear God": Prayers That Open Hearts and Spirits 3. Rueben P. Job, Guide to Prayer for ... (Ministers and Other Servants, All God’s People, All Who Seek God, All Who Walk with God) 4. Jane E. Vennard, The Way of Prayer; Praying with Mandalas; Rev. Sharon Seyfarth Garner, A Colorful, Contemplative Practice; Every Step a Prayer (Print Book); Thomas R. Hawkins, Walking as Spiritual Practice 5. Norvene Vest, Gathered in the Word: Praying the Scriptures in Small Groups; Stephen J. Binz and Kaspars and Ruta Poikans, Transformed by God’s Word: Discovering the Power of Lectio and Visio Divina; Christine Valters Paintner and Lucy Wynkoop, Lectio Divina: Contemplative Awakening and Awareness 6. Romans 8:26, Ephesians 6:18, Paul W. Chilcote, Praying in the Wesleyan Spirit 7. Annonymous, The Way of a Pilgrim(19th century, Russia); Ron DelBene, The Breath of Life: A Simple Way to Pray 8. Francis McNutt, Healing; Kristen Vincent, Beads of Healing; Flora Slosson Wuellner, Prayer, Stress and Our Inner Wounds 9. -

Lex Orandi, Lex Credendi: the Doctrine of the Theotokos As a Liturgical Creed in the Coptic Orthodox Church

Journal of Coptic Studies 14 (2012) 47–62 doi: 10.2143/JCS.14.0.2184687 LEX ORANDI, LEX CREDENDI: THE DOCTRINE OF THE THEOTOKOS AS A LITURGICAL CREED IN THE COPTIC ORTHODOX CHURCH BY BISHOY DAWOOD 1. Introduction In the Surah entitled “The Table Spread” in the Quran, Mohammed, the prophet of Islam, proclaimed a long revelation from God, and in a part that spoke of the role of Mary and teachings of Jesus, the following was mentioned: “And behold! Allah will say: ‘O Jesus the son of Mary! Did you say to men, ‘worship me and my mother as gods in derogation of Allah’?’” (Sura 5:116).1 It is of note here that not only the strict mono- theistic religion of Islam objected to the Christian worshipping of Jesus as God, but it was commonly believed that Christians also worshipped his mother, Mary, as a goddess. This may have been the result of a mis- understanding of the term Theotokos, literally meaning “God-bearer”, but also means “Mother of God”, which was attributed to Mary by the Christians, who used the phrase Theotokos in their liturgical worship. Likewise, in Protestant theology, there was a reaction to the excessive adoration of the Virgin Mary in the non-liturgical devotions of the churches of the Latin West, which was termed “Mariolatry.” However, as Jaroslav Pelikan noted, the Eastern churches commemorated and cel- ebrated Mary as the Theotokos in their liturgical worship and hymnology.2 The place of the Theotokos in the liturgical worship of the Eastern Chris- tian churches does not only show the spiritual relation between the Virgin Mother and the people who commemorate her, but it is primarily a creedal affirmation of the Christology of the believers praying those hymns addressed to the Theotokos. -

Acquired Contemplation Full

THE ART OF ACQUIRED CONTEMPLATION FOR EVERYONE (Into the Mystery of God) Deacon Dr. Bob McDonald ECCE HOMO Behold the Man Behold the Man-God Behold His holy face Creased with sadness and pain. His head shrouded and shredded with thorns The atrocious crown for the King of Kings Scourged and torn with forty lashes Humiliated and mockingly adored. Pleading with love rejected Impaled by my crucifying sins Yet persisting in his love for me I see all this in his tortured eyes. So, grant me the grace to love you As you have loved me That I may lay down my life in joy As you have joyfully laid down your life for me. In the stillness I seek you In the silence I find you In the quiet I listen For the music of God. THE ART OF ACQUIRED CONTEMPLATION Chapter 1 What is Acquired Contemplation? Chapter 2 The Christian Tradition Chapter 3 The Scriptural Foundation Chapter 4 The Method Chapter 5 Expectations Chapter 6 The Last Word CHAPTER 1 WHAT IS ACQUIRED CONTEMPLATION? It will no doubt come as a surprise For the reader to be told that acquired contemplation is indeed somethinG that can be “acquired” and that it is in Fact available to all Christians in all walKs oF liFe. It is not, as is commonly held, an esoteric practice reserved For men and women oF exceptional holiness. It is now Known to possess a universal potential which all oF us can enjoy and which has been larGely untapped by lay Christians For niGh on 2000 years. -

Compassion for Animals in the Orthodox Church

International Journal of Orthodox Theology 10:2 (2019) 9 urn:nbn:de:0276-2019-2025 His Eminence Kallistos Ware, Metropolitan of Diokleia Compassion for Animals in the Orthodox Church Abstract In this article, His Eminence Metro- politan Kallistos Ware deals with the question about the place of animals in the liturgical and theological world of the Orthodox Church. “The art of the icon is par excellence a liturgical art.” Therefore, if we can find icons with animals and plants or stars and all nature, we might understand this as an eschatological view of the uni- verse. “We humans are not saved from the world but with the world; and that means, with the animals.” Another meaningful question of this article is: “Do animals have souls?” “Even if animals are not ensouled, yet they are undoubtedly sentient. They are responsive and vulnerable. (…) As His Eminence Kallistos living beings, sensitive and easily Ware, Metropolitan of hurt, they are to be viewed as a Diokleia 10 His Eminence Kalistos Ware, Metropolitan of Diokleia 'Thou', not an 'It', (…) not as objects to be exploited and manip- ulated but as subjects, capable of joy and sorrow, of happiness and affliction. They are to be approached with gentleness and tenderness; and, more than that, with respect and reverence, for they are precious in God's sight.” Keywords Compassion, animals, Orthodox Church, worship, soul What is a merciful heart? It is a heart on fire for the whole of creation, for humankind, for the birds, for the animals, for the demons, for all that exists. St Isaac the Syrian (7th century) 1 A place for animals in our worship? As I sit writing at my table, I have before me a Russian icon of the martyrs St Florus and St Laurus. -

Orthodox Books

Orthodox Books Orthodoxy:Introductions and Overviews Ancient Faith Topical Series Booklets Cclick here^ The Cambridge Companion to Orthodox Christian Theology - Cambridge Companions to Religion, Mary Cunningham & Elizabeth Theokritoff Eastern Orthodox Christianity: A Western Perspective, Daniel B. Clendenin Encountering the Mystery: Understanding Orthodox Christianity Today, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology, Fr Andrew Louth Introducing the Orthodox Church-Its Faith and Life, Fr. Anthony Coniaris The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Culture, Fr John McGuckin The Orthodox Faith Series, Fr Thomas Hopko The Orthodox Way, Metropolitan Kallistos Ware Doctrine After Death, Vassilios Bakoyiannis The Deification of Man, Georgios Mantzaridis The Mystery of Christ, Fr. John Behr The Mystery of Death, Nikolaos Vassiliadis The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church, Fr Vladimir Lossky The Nicene Faith, vols 1 and 11, Fr. John Behr Church History The Christian Tradition 2: The Spirit ofEastern Christendom 600-1700,Jaroslav Pelikan The Great Church in Captivity: A Study of the Patriarchate of Constantinople from the Eve of the Turkish Conquest to the Greek War ofIndependence, Steven Runciman History of the Byzantine State, George Ostrogorsky The Lives of Orthodox Saints, Ormylia Monastery The Orthodox Church, Metropolitan Kallistos Ware Liturgy and Sacraments The Divine Liturgy: A Commentary in the Light of the Fathers, Hieromonk Gregorios and Elizabeth Theokritoff The Eucharist: -

The Hermeneutics of John Cassian in Conference 14

Logos: A Journal of Eastern Christian Studies Vol. 59 (2018) Nos. 1–4, pp. 263–275 The Monastic Life as Exegesis: The Hermeneutics of John Cassian in Conference 14 Thomas Deutsch Today, faith in the revelation of scripture is not a prerequi- site for becoming a successful scripture scholar. Although many contemporary scholars consider unbelief a prerequisite for analyzing and interpreting scriptures unbiasedly,1 the monk John Cassian (d. circa 435 C.E.) would see such lack of faith as detrimental to the entire process of understanding the scrip- tures. This divergence of opinion results in part because these contemporary scholars and Cassian view the end of scriptural interpretation differently. While a contemporary agnostic scholar strives in his or her exegetical work primarily for eru- dition, originality, and positive peer reception, Cassian wants to unlock the meaning of scriptures for the sake of living a life of unceasing prayer and encounter with God. 1 D.Z. Phillips describes the hermeneutical situation today in terms of a false dichotomy between a hermeneutics of recollection, which presupposes belief on the part of the interpreter in the religious texts being analyzed, and a her- meneutics of suspicion, which sees the unbelief of the interpreter as his or her greatest tool for accessing the meaning of the religious text, since the re- ligious worldview of the text hides or warps the truth of the text. As a middle position between these two extremes, Phillips offers the hermeneutic of con- templation, which allows the interpreter to accept the religious worldview of sacred texts for the purpose of interpretation without actually believing in the worldview presupposed by the text. -

Consciousness of God As God Is: the Phenomenology of Christian Centering Prayer

CONSCIOUSNESS OF GOD AS GOD IS: THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF CHRISTIAN CENTERING PRAYER BY BENNO ALEXANDER BLASCHKE A dissertation submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington (2017) Abstract In this study I aim to give an alternative approach to the way we theorise in the philosophy and comparative study of mysticism. Specifically, I aim to shift debate on the phenomenal nature of contemplative states of consciousness away from textual sources and towards reliable and descriptively rich first-person data originating in contemporary practices of lived traditions. The heart of this dissertation lies in rich qualitative interview data obtained through recently developed second-person approaches in the science of consciousness. I conducted in-depth phenomenological interviews with 20 Centering Prayer teachers and practitioners. The interviews covered the larger trajectory of their contemplative paths and granular detail of the dynamics of recent seated prayer sessions. I aided my second-person method with a “radical participation” approach to fieldwork at St Benedict’s Monastery in Snowmass. In this study I present nuanced phenomenological analyses of the first-person data regarding the beginning to intermediate stages of the Christian contemplative path, as outlined by the Centering Prayer tradition and described by Centering Prayer contemplatives. My presentation of the phenomenology of Centering Prayer is guided by a synthetic map of Centering Prayer’s (Keating School) contemplative path and model of human consciousness, which is grounded in the first-person data obtained in this study and takes into account the tradition’s primary sources. -

The Study of the Fundamentals of Martin Luther's Theology in The

The Study of the Fundamentals of Martin Luther’s Theology in the Light of Ecumenism 1 Tuomo Mannermaa Translated and edited by Kirsi Stjerna It is not unusual in the history of academic disciplines that new ideas concerning the fundamentals of a particular discipline emerge either by accident or as a result of impulses from another field of scholarship. This is the case also in today’s Luther research. Two particular fields can be named from most recent history, fields with significant impulses for new insights: ecumenism and philosophy. The philosophical impulses are connected with the task of locating Luther’s theology in regard to both scholasticism, which preceded Luther, and the philosophy of the modern times, which succeeded him. Ecumenism presents its own challenges for Luther research and Lutheran theological tradition. It is the latter issue that I wish to address here, touching upon the issues related to philosophy only as far as it is helpful in light of ecumenical questions at stake. The ecumenical impulses originate, above all, from two sources: Lutheran–Orthodox theological discussions, on the one hand, and Lutheran–Catholic theological encounters, on the other. The challenge issued to Luther research by Lutheran–Orthodox discussions lies in the theme “Luther and the doctrine of divinization,” whereas Lutheran–Catholic cooperation in Luther research has set out to clarify the theme, “Luther as a theologian of love.” Especially the late Catholic Luther specialist Peter Manns has unraveled the latter topic wit h his fruitful Luther interpretation. The first of these two topics, “Luther and theosis (divinization),” is fundamental in the sense that it gives expression to the patristic standard of comparison that all these three denominations share and that can serve as a starting point in their process toward a common understanding. -

“Until the Christian World Begins to Read Its Own Sources with the Contemplative Mind That Is Offered Here, I See Little Hope for Its in Depth Renewal

“Until the Christian world begins to read its own sources with the contemplative mind that is offered here, I see little hope for its in depth renewal. The argumentative mind that has dominated so much of our recent past has not served history well. Vincent Pizzuto is offering us both inspiration and very readable scholarship here. This is the Great Tradition!” —Fr. Richard Rohr, OFM Center for Action and Contemplation Albuquerque, New Mexico “Denizens of the land of silence owe a debt of gratitude to Vincent Pizzuto for the gift of this book. Clearly written and based on solid scholarship, grounded in Scripture itself, the author clarifies the simplest of truths: to become a contemplative is quite simply a matter of becoming fully normal. Paradoxically our becoming natural involves a lifetime of loves soul-sifting. As Meister Eckhart puts it: ‘The eye with which I see God is the same eye with which God sees me.’ One seeing, one loving, one knowing.” —Martin Laird, OSA Professor of Early Christian Studies Villanova University “A magnificent, nutritious book of spiritual counsel, both visionary and compassionate! Contemplating Christ patiently trains us to rethink familiar texts, feelings, and attitudes by recovering the grandeur of the cosmic Christ from the Gospels, the hymn of Colossians 1, and the teachers of ancient Christianity. This work of mystagogy grasps anew the ‘transgressive’ power of the Incarnation that ‘has made mystics of us all,’ and offers practical ways to live into our wondrous ‘divinized’ identity after baptism. At the same time, it performs microsurgery upon our spiritual practices and predilections (its rethinking of asceticism and of demonic power is particularly fine). -

Gregory Palamas at the Council of Blachernae, 1351 Papadakis, Aristeides Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1969; 10, 4; Proquest Pg

Gregory Palamas at the Council of Blachernae, 1351 Papadakis, Aristeides Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1969; 10, 4; ProQuest pg. 333 Gregory Palamas at the Council of Blachernae, 1351 Aristeides Papadakis HE STORY of the last centuries of Byzantium is one of shrinking Tfrontiers and inevitable disintegration, graphically illustrated by the disasters of Manzikert (1071) and Myriocephalon (1176). The final disaster of 1453 only marks the end of a story the outcome of which had long been determined. Curiously enough, however, these years of increasing decay, when Byzantium proved Ha marvel of tenacity,"1 were also years of extraordinary vitality in such areas as Byzantine theology and art. The profound puzzle of cultural energy amidst political inertia and exhaustion is best illustrated by hesychasm -a movement long organic to Byzantine spirituality, but which first gained momentum with its first eminent exponent, Gregory Palamas, theologian and monk of Mount Athos, and subsequent archbishop of Thessalonica. Happily, confusion and obSCUrity no longer shroud the personality and achievement of Gregory Palamas. Recent research has shown that Pal amite theology-the cause celebre that shook the fabric of Byzantine society in the 1340s-constitutes an organic continuation of the strong biblical and patristic tradition of the Byzantine Church. The theology of Palamas is in no wayan innovative or heretical deviation from orthodoxy (and therefore of marginal importance as some have thought).2 No one has contributed more to making Palamas accessible 1 Cf. G. Ostrogorsky in CMedHI IV.l (Oxford 1968) 367; J. M, Hussey, "Gibbon Re written: Recent Trends in Byzantine Studies," in Rediscovering Eastern Christendom, ed. -

The Ways of Byzantine Philosophy

The Ways of Byzantine Philosophy The Ways of Byzantine Philosophy Edited by Mikonja Knežević Sebastian Press Alhambra, California The ways of Byzantine philosophy / Mikonja Knežević, editor. — Alham- bra, California : Sebastian Press, Western American Diocese of the Ser- bian Orthodox Church, Faculty of Philosophy, Kosovska Mitrovica, 2015. 476 pages ; 23 cm. (Contemporary Christian thought series ; no. 32) ISBN: 978-1-936773-25-1 1. Philosophy—Byzantine Empire. 2. Philosophy, Ancient. 3. Philosophy, Medieval. 4. Christian philosophy. 5. Christianity—Philosophy. 6. Ortho- dox Eastern Church—Byzantine Empire—Doctrines—History. 7. Ortho- dox Eastern Church—Theology. 8. Philosophy and religion—Byzantine Empire. 9. Theologians—Byzantine Empire. 10. Christian saints—Byzan- tine Empire—Philosophy. 11. Byzantine empire—Church history. 12. Byzantine empire—Civilization. I. Knežević, Mikonja, 1978– II. Series. Contents Georgi Kapriev Philosophy in Byzantium and Byzantine Philosophy .....................1 Dušan Krcunović Hexaemeral Anthropology of St. Gregory of Nyssa: “Unarmed Man” (ἄοπλος ὁ ἄνθρωπος) ................................9 Torstein Theodor Tollefsen St. Gregory the Theologian on Divine Energeia in Trinitarian Generation ..........................................25 Ilaria L. E. Ramelli Proclus and Christian Neoplatonism: Two Case Studies . 37 Dmitry Birjukov Hierarchies of Beings in the Patristic Thought. Gregory of Nyssa and Dionysius the Areopagite ........................71 Johannes Zachhuber Christology after Chalcedon and the Transformation of the Philosophical Tradition: Reflections on a neglected topic . 89 José María Nieva Anthropology of Conversion in Dionysius the Areopagite . 111 Filip Ivanović Eros as a Divine Name in Dionysius the Areopagite . 123 Basil Lourié Leontius of Byzantium and His “Theory of Graphs” against John Philoponus ..........................................143 i Vladimir Cvetković The Transformation of Neoplatonic Philosophical Notions of Procession (proodos) and Conversion (epistrophe) in the Thought of St. -

Taught by God: Teaching and Spiritual Formation by Karen-Marie Yust and E

For published version: See Interpreation 61 (3): 350. Taught by God: Teaching and Spiritual Formation by Karen-Marie Yust and E. Byron Anderson, Chalice Press, St. Louis, 2006. Pp. 186. $21.99. ISBN 0827236492. Religious educators need a vibrant spiritual life. This seems obvious but it is easy to overlook. When we think about education, we immediately think about our own schooling where we were required to regurgitate information. We do not think about deeper dimensions of formation and what this demands of the teacher. But “can we teach Christians to pray,” authors Karen-Marie Yust and E. Byron Anderson stress again and again, “if we ourselves do not know a life of prayer?” (p. 19). Taught by God is designed to address this oversight. It retrieves a rich variety of paths to Christian wisdom. In fact, a more accurate subtitle is “Spiritual Resources for Religious Educators.” Organized around a four-part exploration of teacher identity, teaching context, models, and evaluation, the book essentially reviews a series of classical texts (Luther, Kierkegaard, Julian of Norwich, John Cassian, Jane de Chantal, Francis de Sales, Anthony, John Bunyan, John Climacus, Thomas à Kempis, Benedict, Catherine of Siena, Diadochos, Ignatius, Henri Nouwen, and Simon Weil) as well as contemporary educational theorists, such as Parker Palmer and Mary Belenky. The summaries of primary texts and secondary source commentary on them makes for dry reading, a problem “easily rectified,” Yust and Anderson say, “through further reading” of the classics (p. 5). Reading this book alongside sample works would enhance its value. Unfortunately the advice of many of these figures stands at real odds with the lives of the book’s likely readers.