Westerly 57-1 Text.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GéZa Von Bolvã¡Ry ̘͙” ˪…˶€ (Ìž'í'ˆìœ¼ë¡Œ)

Géza von Bolváry ì˜í ™” 명부 (작품으로) The Prisoners of Shanghai https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-prisoners-of-shanghai-19840598/actors The Way to the Light https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-way-to-the-light-55635624/actors The Royal Grenadiers https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-royal-grenadiers-56064216/actors The Princess of the Riviera https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-princess-of-the-riviera-28130371/actors Farewell Waltz https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/farewell-waltz-107210116/actors Die Fledermaus https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/die-fledermaus-1212466/actors Schwarzwaldmelodie https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/schwarzwaldmelodie-1238382/actors A Song Goes Round the World https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-song-goes-round-the-world-1304847/actors Once I Will Return https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/once-i-will-return-1308385/actors Flower of the Tisza https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/flower-of-the-tisza-1321620/actors Zauber der Bohème https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/zauber-der-boh%C3%A8me-148379/actors Yes, Yes, Love in Tyrol https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/yes%2C-yes%2C-love-in-tyrol-1544574/actors The Irresistible Man https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-irresistible-man-15805216/actors Premiere https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/premiere-1591914/actors Roses in Tyrol https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/roses-in-tyrol-1609985/actors Schrammeln https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/schrammeln-1643798/actors -

James Daffern 15/09/2020, 21�09

Spotlight: JAMES DAFFERN 15/09/2020, 2109 JAMES DAFFERN C S A 3rd Floor Joel House, 17-21 Garrick Street, London WC2E 9BL Phone: 020-7420 9351 E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.shepherdmanagement.co.uk HARVEY VOICES 49 Greek Street, London W1D 4EG Phone: 020 7952 4361 Mobile: 07739 902784 Photo: Jennie Scott E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.harveyvoices.co.uk Location: Greater London, Appearance: White, England, United Scandinavian, Kingdom Eastern Height: 6' (182cm) European Weight: 13st. 7lb. (86kg) Other: Equity Playing Age: 40 - 50 years Eye Colour: Blue Hair Colour: Dark Brown Hair Length: Short About me: Television Television, Andrew Wallace, PROFESSOR T, Eagle Eye Productions, Indra Siera Television, Jim Bonning, CASUALTY, BBC, Various Television, One Eyed Marc, BIRDS OF A FEATHER, ITV, Martin Dennis Television, Leon, X COMPANY, CBC Television/Sony Pictures Television Television, Ben Owens, DOCTORS (NINE EPS), BBC, Various Television, Zac Glazerbrook, CUFFS, BBC/Tiger Aspect Productions, Kieron Hawkes Television, Natie, RAISED BY WOLVES, C4, Mitchell Altieri Television, Bruce, FLYING HIGH, ZDF, Stephen Bartmann Television, Andrew Hayden, HUNTED, Kudos/HBO/BBC, Daniel Percival/James Strong Television, Ray Keats, WATERLOO ROAD, Shed Productions, Fraser Macdonald Television, Lucas North in Flashback, SPOOKS, BBC Television, Edward Hall Television, Paul Walsh, HOME TIME, BBC Television, Christine Gernon Television, Nathan, RIVER CITY, BBC Television, Semi regular Television, Jimmy Barrett, THE ROYAL, Yorkshire Television, -

Spooks Returns to Dvd

A BAPTISM OF FIRE FOR THE NEW TEAM AS SPOOKS RETURNS TO DVD SPOOKS: SERIES NINE AVALIABLE ON DVD FROM 28TH FEBRUARY 2011 “Who doesn’t feel a thrill of excitement when a new series of Spooks hits our screens?” Daily Mail “It’s a tribute to Spooks’ staying power that after eight years we still care so much” The Telegraph BAFTA Award‐winning British television spy drama Spooks is back for its ninth knuckle‐clenching series and is available on DVD from 28th February 2011 courtesy of Universal Playback. Filled with spy‐tastic extra features, the DVD is a must for any die‐hard Spooks fan. The ninth series of the critically acclaimed Spooks, is filled with dramatic revelations and a host of new characters ‐ Sophia Myles (Underworld, Doctor Who), Max Brown (Mistresses, The Tudors), Iain Glen (The Blue Room, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider), Simon Russell Beale (Much Ado About Nothing, Uncle Vanya) and Laila Rouass (Primeval, Footballers’ Wives). Friendships will be tested and the depth of deceit will lead to an unprecedented game of cat and mouse and the impact this has on the team dynamic will have viewers enthralled. Follow the team on a whirlwind adventure tracking Somalian terrorists, preventing assassination attempts, avoiding bomb efforts and vicious snipers, and through it all face the personal consequences of working for the MI5. The complete Spooks: Series 9 DVD boxset contains never before seen extras such as a feature on The Cost of Being a Spy and a look at The Downfall of Lucas North. Episode commentaries with the cast and crew will also reveal secrets that have so far remained strictly confidential. -

Simon Gillman Production Sound Mixer / Sound Recordist

PRINCESTONE ( +44 (0) 208 883 1616 8 [email protected] SIMON GILLMAN PRODUCTION SOUND MIXER / SOUND RECORDIST TELEVISION CREDITS include: Title Director Production Comp. / Producer MAXXX O-T Fagbenle, Luti Media, OTT Lion Ltd, E4 / (6 x 30 mins) Comedy Series Nick Collett Ali Carron Cast: O-T Fagbenle, Helen Monks, Chris Meloni, Pippa Bennett-Warner, Alan Assad SCARBOROUGH Derren Litten BBC Comedy, BBC 1 / (6 x 30 mins) Warm Comedy Series Gill Isles Cast: Jason Manford, Catherine Tyldesley, Stephanie Cole, Maggie Ollerenshaw THE ATHENA Steve Hughes, Isabelle Sieb, Bryncoed Productions, Sky / (26 x 30 mins) Teen Drama (BAFTA nominated) Max Myers, Paul Walker Paul McKenzie Cast: Ella Balinska, Lucy Gaskell, Oliver Dench, Rebecca Rycroft Tafline Steen, Basil Eidenbenz, Eve Austin UNCLE series 3 Oliver Refson, Baby Cow Productions, BBC 3 / (7 x 30 mins) Comedy Series Lilah Vandenburgh Alison MacPhail Cast: Nick Helm, Elliot Speller-Gillott MARLEY’S GHOST series 2 Jonathan Gershfield Objective Media / John Stanley, (6 x 40 mins) Comedy Series James Dean Cast: Sarah Alexander, John Hannah, Jo Joyner ROVERS Craig Cash Jelly Legs, Sky TV / (6 x 30 mins) Football Based Comedy Drama Gill Isles Cast: Craig Cash, Sue Johnston, Steve Speirs, Joe Wilkinson, David Earl, Pearce Quigley AFTER HOURS Craig Cash Jelly Legs, Sky TV / (6 x 30 mins) Sweetly Comedic Drama Gill Isles Cast: Ardal O’Hanlon, John Thomson, Rob Kendrick, Jaime Winstone HOLBY CITY - 2012 - 2019 Jamie Anette, BBC / (multiple x 60 mins) Single Camera Hospital Drama Richard Signy, Justin -

Richard Armitage

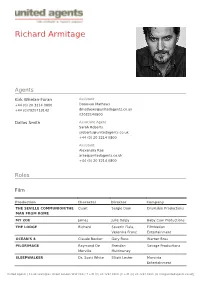

Richard Armitage Agents Kirk Whelan-Foran Assistant +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Donovan Mathews +44 (0)7920713142 [email protected] 02032140800 Dallas Smith Associate Agent Sarah Roberts [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Assistant Alexandra Rae [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE SEVILLE COMMUNION/THE Quart Sergio Dow Drumskin Productions MAN FROM ROME MY ZOE James Julie Delpy Baby Cow Productions THE LODGE Richard Severin Fiala, FilmNation Veronika Franz Entertainment OCEAN'S 8 Claude Becker Gary Ross Warner Bros PILGRIMAGE Raymond De Brendan Savage Productions Merville Muldowney SLEEPWALKER Dr. Scott White Elliott Lester Marvista Entertainment United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company BRAIN ON FIRE Tom Cahalan Gerard Barrett Broad Green Pictures ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING King Oleron James Bobin Walt Disney Pictures GLASS URBAN AND THE SHED CREW Chop Candida Brady Blenheim Films THE HOBBIT: THE BATTLE OF Thorin Peter Jackson MGM THE FIVE ARMIES Oakenshield INTO THE STORM Gary Morris Steven Quale Broken Road/New Line THE HOBBIT - THE DESOLATION Thorin Peter Jackson MGM OF SMAUG Oakenshield THE HOBBIT - AN UNEXPECTED Thorin Peter Jackson MGM JOURNEY Oakenshield CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE FIRST Heinz Kruger Joe Johnston Marvel AVENGER CLEOPATRA Epiphanes Frank Roddan Alexandria Films FROZEN Steven Juliet McKoen Liminal Films MACBETH Angus -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Escaping the Honeytrap Representations and Ramifications of the Female Spy on Television Since 1965 Karen K. Burrows Submitted in fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media and Cultural Studies at the University of Sussex, May 2014 3 University of Sussex Karen K. Burrows Escaping the Honeytrap: Representations and Ramifications of the Female Spy on Television Since 1965 Summary My thesis interrogates the changing nature of the espionage genre on Western television since the middle of the Cold War. It uses close textual analysis to read the progressions and regressions in the portrayal of the female spy, analyzing where her representation aligns with the achievements of the feminist movement, where it aligns with popular political culture of the time, and what happens when the two factors diverge. I ask what the female spy represents across the decades and why her image is integral to understanding the portrayal of gender on television. I explore four pairs of television shows from various eras to demonstrate the importance of the female spy to the cultural landscape. -

Media – History

Matej Santi, Elias Berner (eds.) Music – Media – History Music and Sound Culture | Volume 44 Matej Santi studied violin and musicology. He obtained his PhD at the University for Music and Performing Arts in Vienna, focusing on central European history and cultural studies. Since 2017, he has been part of the “Telling Sounds Project” as a postdoctoral researcher, investigating the use of music and discourses about music in the media. Elias Berner studied musicology at the University of Vienna and has been resear- cher (pre-doc) for the “Telling Sounds Project” since 2017. For his PhD project, he investigates identity constructions of perpetrators, victims and bystanders through music in films about National Socialism and the Shoah. Matej Santi, Elias Berner (eds.) Music – Media – History Re-Thinking Musicology in an Age of Digital Media The authors acknowledge the financial support by the Open Access Fund of the mdw – University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna for the digital book pu- blication. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche National- bibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http:// dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeri- vatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commercial pur- poses, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting rights@transcript- publishing.com Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. -

Terrorism, Ethics and Creative Synthesis in the Post-Capitalist Thriller

The Post 9/11 Blues or: How the West Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Situational Morality - Terrorism, Ethics and Creative Synthesis in the Post-Capitalist Thriller Patrick John Lang BCA (Screen Production) (Honours) BA (Screen Studies) (Honours) Flinders University PhD Dissertation School of Humanities and Creative Arts (Screen and Media) Faculty of Education, Humanities & Law Date of Submission: April 2017 i Table of Contents Summary iii Declaration of Originality iv Acknowledgements v Chapter One: A Watershed Moment: Terror, subversion and Western ideologies in the first decade of the twenty-first century 1 Chapter Two: Post-9/11 entertainment culture, the spectre of terrorism and the problem of ‘tastefulness’ 18 A Return to Realism: Bourne, Bond and the reconfigured heroes of 21st century espionage cinema 18 Splinter cells, stealth action and “another one of those days”: Spies in the realm of the virtual 34 Spies, Lies and (digital) Videotape: 21st Century Espionage on the Small Screen 50 Chapter Three: Deconstructing the Grid: Bringing 24 and Spooks into focus 73 Jack at the Speed of Reality: 24, torture and the illusion of real time or: “Diplomacy: sometimes you just have to shoot someone in the kneecap” 73 MI5, not 9 to 5: Spooks, disorder, control and fighting terror on the streets of London or: “Oh, Foreign Office, get out the garlic...” 91 Chapter Four: “We can't say anymore, ‘this we do not do’”: Approaching creative synthesis through narrative and thematic considerations 108 Setting 108 Plot 110 Morality 111 Character 114 Cinematic aesthetics and the ‘culture of surveillance’ 116 The role of technology 119 Retrieving SIGINT Data - Documenting the Creative Artefact 122 ii The Section - Series Bible 125 The Section - Screenplays 175 Episode 1.1 - Pilot 175 Episode 1.2 - Blasphemous Rumours 239 Episode 1.9 - In a Silent Way 294 Bibliography 347 Filmography (including Television and Video Games) 361 iii Summary The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 have come to signify a critical turning point in the geo-political realities of the Western world. -

Semantron 20 Summer 2020

Semantron 20 Summer 2020 Semantron was founded in 1992 by Dr. Jan Piggott (Head of English, and then Archivist at the College) together with one of his students, Richard Scholar (now Senior Tutor at Oriel College, Oxford and Professor of French and Comparative Literature). The photographs on the front and back covers, and those which start each section, are by Ed Brilliant. Editor’s introduction: ex umbris Neil Croally Summer 2020 Torn between the war against cliché and the rhetoric of praeteritio In late March, purely for entertainment’s sake, I had recourse to the guilty pleasure of watching some episodes of Spooks.1 Soon this turned into an obsessive need to watch the episodes of all ten series. Yes, that is nearly 100 hours of television – for someone who does not own a television. But what was the attraction? At first, I merely indulged a love for representations of the secret world, however inane or fantastic. Co-incidentally and (I suppose) remarkably, there were the Dulwich connections: not only of two of the starring actors, Rupert Penry-Jones and Raza Jaffrey, but also of the use of Sydenham Hill station and the nearby woods as the site of a secret assignation away from the febrile atmosphere of the ‘grid’, and of Crystal Palace Sports Centre as the place where a jihadi cell met under cover of a weekly five-a-side knockabout. But moving through the series, I began to marvel at two apparently incompatible features of the show. The first was the wish, unsurprising in a series about the security services, to dive boldly into ethical dilemmas, more specifically into an examination of Utilitarianism.2 One can only admire the direct, no-nonsense way in which centuries of philosophical reflection are cast aside, as the spies come down without fail in favour of the majoritarian position, whatever the cost to individuals and to themselves. -

Opinions of Film Critics and Viewers

Alexander Fedorov 100 most popular Soviet television movies and TV series: opinions of film critics and viewers Moscow, 2021 Fedorov A.V. 100 most popular Soviet television movies and TV series: opinions of film critics and viewers. Moscow: "Information for all", 2021. 144 p. What does the list of the hundred most popular Soviet television films and TV series look like? How did the press and viewers evaluate and rate these films? In this monograph, for the first time, an attempt is made to give a panorama of the hundred most popular Soviet television films and serials in the mirror of the opinions of film critics, film critics and viewers. The monograph is intended for high school teachers, students, graduate students, researchers, film critics, film experts, journalists, as well as for a circle of readers who are interested in the problems of cinema, film criticism and film sociology. Reviewer: Professor M.P. Thselyh. © Alexander Fedorov, 2021. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ………………………………….................................................................................... 4 100 most popular Soviet television movies and TV series: opinions of film critics and viewers ……………………………........................................................................................... 5 Interview on the release of the book "One Thousand and One Highest Grossing Soviet Movie: Opinions of Film Critics and Viewers"…………………………………………………………….. 119 List of "100 most popular Soviet television films and TV series.......................................... 125 About -

Zusammenfassung Abstract Barbara KORTE the Fading of the Hero In

http://www.interferenceslitteraires.be ISSN : 2031 - 2790 Barbara KORTE The Fading of the Hero in the Spy Genre A Case Study of Spooks (BBC 2002-2011) Zusammenfassung Spionagefiktion suggeriert typischerweise, dass das Heldentum von Geheimagenten prekär ist. Spione lügen, betrügen und töten, und ihre moralische Fragwürdigkeit wird treffend mit dem britischen umgangssprachlichen Ausdruck ‘spook’ erfasst, vom Ursprung her ein Synonym für ‘Geist,.Gespenst’. Aufgrund ihrer moralischen Fragwürdigkeit haben Spione und die Fiktionen, die sie darstellen, eine besondere Affinität zur Idee des ‘verschwindenden’ Heldens und Heldentums. Spionagefiktion projiziert einen Heroismus, dessen Bedeutungen und Manifestationen prekär sind, der erscheint und verschwindet, der in bestimmten Augenblicken aufleuchtet, dann aber wieder verblasst. Der Artikel zeigt dies zunächst für das Spionagegenre per se, dann in einem Close Reading von Spooks (2002-2011), einer von der BBC produzierten Fernsehserie über den Sicherheitsdienst des Vereinigten Königreichs. Die Länge und (Dis-) Kontinuitäten serieller Narration ermöglichen ein komplexes Erzählen und widersprüchliche Charakterzeichnung, einschließlich der Möglichkeit, dass heroisierte Figuren einen bedeutungsvollen und verstörenden Wandel erfahren. Dies erreicht einen Höhepunkt in der neunten Staffel von Spooks, auf die dieser Aufsatz seinen Fokus legt; hier durchlebt der Held einen Wandel seiner Moral und Persönlichkeit , der angesichts seiner früheren Geschichte und der Kenntnisse, die die Zuschauer über ihn aufgebaut haben, nicht vorhersagbar ist. Abstract Spy fiction typically suggests that the heroicity of the secret agent is, at best, an insecure one. Spies lie, deceive and kill, and their moral shadiness is aptly captured in the British colloquial expression ‘spook’, originally a synonym for ‘ghost’. It is this shadiness through which spies and the fictions that depict them have a special affinity to the idea of ‘fading’ heroes and heroism. -

UBC Virtual Graduation | Spring 2021

ubc virtual graduation spring 2021 june 2 Dear Graduate, Today’s virtual ceremony celebrates your very real accomplishment. Your graduation began long before this day. It began when you made the choice to study that extra hour, dedicate yourself more deeply and strive to reach for the degree you had chosen to fully commit your life to pursuing. Many of the people that helped you arrive here today— family, friends, classmates—are watching this ceremony with you. While they may not be physically next to you, they stand with you in spirit, take pride in your achievement and share your joy. We are honoured to have given you a place to discover, inspire others and be challenged beyond what you thought was possible. Yours, UBC TABLE OF CONTENTS The Graduation Journey 2 Lists of Spring 2021 Graduating Students Graduation Traditions 4 The Faculty of Graduate and Chancellor’s Welcome 6 Postdoctoral Studies 21 President’s Welcome 8 The Faculty of Applied Science 30 Musqueam Welcome 10 The Faculty of Arts 36 The Board of Governors & Senate 12 The Faculty of Commerce and Business Administration 47 Scholarships, Medals & Prizes 14 The Faculty of Dentistry 53 The Program of Ceremony 20 The Faculty of Education 54 The Faculty of Forestry 56 The Faculty of Land and Food Systems 58 The Peter A. Allard School of Law 60 The Faculty of Medicine 61 The Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences 63 The Faculty of Science 64 Acknowledgements 70 O Canada 70 Alumni Welcome 71 1 SPRING GRADUATION 2021 THE GRADUATION JOURNEY The UBC graduation journey has been forged by the spirit of the university’s motto, Tuum Est, (meaning ‘it is yours’) since 1915.