Mapping Judah's Fate in Ezekiel's Oracles Against the Nations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partners with God

Partners with God Theological and Critical Readings of the Bible in Honor of Marvin A. Sweeney Shelley L. Birdsong & Serge Frolov Editors CLAREMONT STUDIES IN HEBREW BIBLE AND SEPTUAGINT 2 Partners with God Table of Contents Theological and Critical Readings of the Bible in Honor of Marvin A. Sweeney Abbreviations ix ©2017 Claremont Press Preface xv 1325 N. College Ave Selected Bibliography of Marvin A. Sweeney’s Writings xvii Claremont, CA 91711 Introduction 1 ISBN 978-1-946230-13-3 Pentateuch Is Form Criticism Compatible with Diachronic Exegesis? 13 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rethinking Genesis 1–2 after Knierim and Sweeney Serge Frolov Partners with God: Theological and Critical Readings of the Bible in Exploring Narrative Forms and Trajectories 27 Honor of Marvin A. Sweeney / edited by Shelley L. Birdsong Form Criticism and the Noahic Covenant & Serge Frolov Peter Benjamin Boeckel xxi + 473 pp. 22 x 15 cm. –(Claremont Studies in Hebrew Bible Natural Law Recorded in Divine Revelation 41 and Septuagint 2) A Critical and Theological Reflection on Genesis 9:1-7 Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-946230-13-3 Timothy D. Finlay 1. Bible—Criticism, Narrative 2. Bible—Criticism, Form. The Holiness Redaction of the Abrahamic Covenant 51 BS 1192.5 .P37 2017 (Genesis 17) Bill T. Arnold Former Prophets Miscellaneous Observations on the Samson Saga 63 Cover: The Prophet Jeremiah by Barthélemy d’Eyck with an Excursus on Bees in Greek and Roman Buogonia Traditions John T. Fitzgerald The Sword of Solomon 73 The Subversive Underbelly of Solomon’s Judgment of the Two Prostitutes Craig Evan Anderson Two Mothers and Two Sons 83 Reading 1 Kings 3:16–28 as a Parody on Solomon’s Coup (1 Kings 1–2) Hyun Chul Paul Kim Y Heavenly Porkies 101 The Psalm in Habakkuk 3 263 Prophecy and Divine Deception in 1 Kings 13 and 22 Steven S. -

(Leviticus 10:6): on Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible

1 “Do not bare your heads and do not rend your clothes” (Leviticus 10:6): On Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible Yael Shemesh, Bar Ilan University Many agree today that objective research devoid of a personal dimension is a chimera. As noted by Fewell (1987:77), the very choice of a research topic is influenced by subjective factors. Until October 2008, mourning in the Bible and the ways in which people deal with bereavement had never been one of my particular fields of interest and my various plans for scholarly research did not include that topic. Then, on October 4, 2008, the Sabbath of Penitence (the Sabbath before the Day of Atonement), my beloved father succumbed to cancer. When we returned home after the funeral, close family friends brought us the first meal that we mourners ate in our new status, in accordance with Jewish custom, as my mother, my three brothers, my father’s sisters, and I began “sitting shivah”—observing the week of mourning and receiving the comforters who visited my parent’s house. The shivah for my father’s death was abbreviated to only three full days, rather than the customary week, also in keeping with custom, because Yom Kippur, which fell only four days after my father’s death, truncated the initial period of mourning. Before my bereavement I had always imagined that sitting shivah and conversing with those who came to console me, when I was so deep in my grief, would be more than I could bear emotionally and thought that I would prefer for people to leave me alone, alone with my pain. -

Ezekiel 15.Pdf

The Vine Ezekiel 15 The Vine Introduction • For a few years I experimented with growing Concord grapes in our backyard. • It was a complete failure. The Vine Introduction • I cut down the vine, let it dry out and eventually burned it. • To be fair to the grapevine, it probably needed a bigger yard and more effort than I was able to give to it. The Vine Introduction • We shouldn’t blame the vine in this case. • The vine or vineyard is a theme that runs through much of the Bible. The Vine Introduction • Read Isaiah 5:1-7. The Vine Introduction • Read Isaiah 5:1-7. • The problem with the nation was its fruit – or its lack of good fruit, to be precise. • Ezekiel will elaborate on this theme. The Vine Ezekiel 15 The Vine Ezekiel 15 • The downfall of the nation began in the days of Isaiah. • It was completed in the days of Ezekiel. The Vine Ezekiel 15 • A vine that bears no fruit – or bad fruit – is truly worthless. • As Ezekiel points out, it’s wood isn’t really useful for anything except to burn. The Vine Ezekiel 15 • God appointed Israel to be a blessing to the nations. • Instead they were unfaithful and bore bad fruit. • Then the vine was burned and its wood became even more useless than it was at the beginning. The Vine Ezekiel 15 This situation is mentioned because of what actually happened to Jerusalem. The city was charred (partially burned) by the fire of the Babylonians in 597 BC, but survived. -

THRU the BIBLE EXPOSITION Ezekiel

THRU THE BIBLE EXPOSITION Ezekiel: Effective Ministry To The Spiritually Rebellious Part XXXIII: Illustrating Israel's Great Pain From God's Discipline (Ezekiel 24:15-27) I. Introduction A. When God disciplines man for sin, His discipline is very painful that it might produce the desired repentance. B. Ezekiel 24:15-27 provides an illustration of this truth, and we view this passage for our insight (as follows): II. Illustrating Israel's Great Pain From God's Discipline, Ezekiel 24:15-27. A. God made Ezekiel a moving illustration of the painful shock his fellow Hebrew captives would experience at the fall of Jerusalem in God's judgment, the destruction of their beloved temple and children, Ezek. 24:15-24: 1. After God's prophet in Ezekiel 24:1-14 announced that the Babylonian army had begun its siege of Jerusalem, the Lord told Ezekiel that He was going to take the delight of his eyes, Ezekiel's wife, away from him in death with a "blow," that is, to take her life very suddenly, Ezekiel 24:15-16a NIV. 2. Regardless of the intense shock of such event, Ezekiel was not to mourn or weep, not to let tears run from his eyes, but to sigh silently, to perform no public mourning act for the dead, Ezek. 24:16b-17a. Rather, he was to bind on his turban, put on his sandals, not cover the lower part of his face nor eat any food, highly unusual behavior for a man who had just tragically, suddenly lost his beloved wife, Ezekiel 24:17b NIV. -

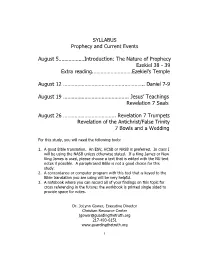

Prophecy and Current Events

SYLLABUS Prophecy and Current Events August 5………………Introduction: The Nature of Prophecy Ezekiel 38 - 39 Extra reading.………………………Ezekiel’s Temple August 12 …………………………………….………….. Daniel 7-9 August 19 ………………………………………. Jesus’ Teachings Revelation 7 Seals August 26 ………………………………. Revelation 7 Trumpets Revelation of the Antichrist/False Trinity 7 Bowls and a Wedding For this study, you will need the following tools: 1. A good Bible translation. An ESV, HCSB or NASB is preferred. In class I will be using the NASB unless otherwise stated. If a King James or New King James is used, please choose a text that is edited with the NU text notes if possible. A paraphrased Bible is not a good choice for this study. 2. A concordance or computer program with this tool that is keyed to the Bible translation you are using will be very helpful. 3. A notebook where you can record all of your findings on this topic for cross referencing in the future; the workbook is printed single sided to provide space for notes. Dr. JoLynn Gower, Executive Director Christian Resource Center [email protected] 217-493-6151 www.guardingthetruth.org 1 INTRODUCTION The Day of the Lord Prophecy is sometimes very difficult to study. Because it is hard, or we don’t even know how to begin, we frequently just don’t begin! However, God has given His Word to us for a reason. We would be wise to heed it. As we look at prophecy, it is helpful to have some insight into its nature. Prophets see events; they do not necessarily see the time between the events. -

Ezekiel Chapter 13

Ezekiel Chapter 13 Ezekiel 13:1 "And the word of the LORD came unto me, saying," This Word of the LORD is to a special group of people, and not to the entire nation. This is a totally different prophecy from the last lesson. Ezekiel 13:2 "Son of man, prophesy against the prophets of Israel that prophesy, and say thou unto them that prophesy out of their own hearts, Hear ye the word of the LORD;" This prophesy is directed to the false prophets, themselves. These prophets should not be ministering to anyone, because they do not even know the truth themselves. False prophets had long flourished in Judah and had been transported to Babylon as well. Here God directs Ezekiel to indict those false prophets for futile assurances of peace. Then His attention turns to lying prophetesses (in verses 17-23). Those who would be teachers then, or now, must first learn themselves. Many feel called to the ministry, but they do not prepare. The greatest preparation a man can make is to thoroughly study the Word of God. The Truth is in the Word of God. A person should never go into the ministry as a vocation. The ministry must be a call. In the case of the true prophets, their mouths are not their own. God speaks to the people through them. The words are not from the prophets' hearts, but from the heart of God. The false prophets in Israel were not innocently in error. They had made up these prophecies themselves, pretending the message came from God. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

Baasha of Ammon

Baasha of Ammon GARY A. RENDSBURG Cornell University 1lVD'i' 'Xtl1' i1'1::J' i"'~ 1,T The identification of the members of the western coalition who fought Shal maneser HI at the battle of Qarqar has engaged Assyriologists since the 19th century. Among the more elusive members of the alliance has been Ba-J-sa miir 1 Ru-bu-bi .KUR A-ma-na-a-a, listed in the Monolith Inscription, column II, line 95. The majority view holds that the toponym A-ma-na-a-a refers to Ammon. the small state located in Transjordan = biblical cammon (Gen. 19:38, etc.). This iden tification ,:>riginated among late 19th and early 20th century scholars,2 is repeated in more recent works,3 and appears in standard translations.4 The ~llinority view was first offered by E. Forrer,S who identified the word with Amana, the mountainous region of southern Syria, more specifically the It is my pleasure to thank Peter Machinist and Samuel M. Paley whose helpful suggestions I have incorporated into this article. 1. For the original, see H. C. Rawlinson, The Cuneiform Inscriptions of Western Asia (London, 1870),3: pliltes 7-8. 2. F. Delitzsch, Wo lag das Paradies ? (Leipzig, 1881),294; F. Hommel. Geschichte Babylolliells und Assyriells (Berlin, 1885), 609; C. P. Tiele, Babylollisch·assyrische Geschichte (Gotha, 1886). 201; E. Schrader. Sammlung von assyrischen und babylonischen Textell (Berlin, (889), I: 173; R. W. Rogers, A History of Babylollia and Assyria (New York, 1901),77; H. Winckler, The History of Babylonia and Assyria (New York, 1907),220; A. -

Ezekiel 13:1-23

False Prophets Condemned - Ezekiel 13:1-23 Topics: Anger, Death, Deceit, Discouragement, Foolishness, Freedom, Judgment, Listening, Lying, Occult, Opposition, Peace, Power, Prophecy, Righteousness, Salvation, Suffering Open It 1. For what different reasons do people listen to fortune-tellers and psychics? * 2. When have you refused to face reality in a specific situation? Explore It 3. To whom did God tell Ezekiel to prophesy? (13:1-2) * 4. Where did the false prophets get the message they were preaching? (13:2) 5. What had the prophets of Israel actually seen? (13:3) 6. To what animal did Ezekiel compare the false prophets? (13:4) * 7. What had the false prophets not done that God expected of His prophets? (13:5) 8. What verbal “signature” did the prophets use to give their words more weight? (13:6-7) 9. What attitude did God take toward the false prophets? (13:8) 10. In what way did the Lord promise to silence the false prophets? (13:9) 11. With what pleasing message were Israel’s prophets leading the people astray? (13:10) 12. What did God predict about the flimsy wall covered with whitewash? (13:11-12) 13. What imagery did God use to portray the fate of the false prophets and their lies? (13:13-16) 14. What practices did God condemn in the prophetesses of Israel? (13:17-19) 15. What did God promise to do for the people who had been ensnared by the prophetesses? (13:20- 21) * 16. How did the false prophets have justice completely reversed? (13:22) 17. -

Exploring Zechariah, Volume 2

EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 VOLUME ZECHARIAH, EXPLORING is second volume of Mark J. Boda’s two-volume set on Zechariah showcases a series of studies tracing the impact of earlier Hebrew Bible traditions on various passages and sections of the book of Zechariah, including 1:7–6:15; 1:1–6 and 7:1–8:23; and 9:1–14:21. e collection of these slightly revised previously published essays leads readers along the argument that Boda has been developing over the past decade. EXPLORING MARK J. BODA is Professor of Old Testament at McMaster Divinity College. He is the author of ten books, including e Book of Zechariah ZECHARIAH, (Eerdmans) and Haggai and Zechariah Research: A Bibliographic Survey (Deo), and editor of seventeen volumes. VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Boda Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-201-0) available at http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx Cover photo: Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com Mark J. Boda Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 ANCIENT NEAR EAST MONOGRAPHS Editors Alan Lenzi Juan Manuel Tebes Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach C. L. Crouch Esther J. Hamori Chistopher B. Hays René Krüger Graciela Gestoso Singer Bruce Wells Number 17 EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah by Mark J. -

The Prophets Speak on Forced Migration

THE PROPHETS SPEAK ON FORCED MIGRATION Press SBL A ncient Israel and Its Literature Thomas C. Römer, General Editor Editorial Board: Mark G. Brett Marc Brettler Cynthia Edenburg Konrad Schmid Gale A. Yee Press SBLNum ber 21 THE PROPHETS SPEAK ON FORCED MIGRATION Edited by Mark J. Boda, Frank Ritchel Ames, John Ahn, and Mark Leuchter Press SBL Press SBLAt lanta C opyright © 2015 by SBL Press A ll rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office,S BL Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The prophets speak on forced migration / edited by Mark J. Boda, Frank Ritchel Ames, John Ahn, and Mark Leuchter. p. cm. — (Society of Biblical Literature : Ancient Israel and its literature ; 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “In this collection of essays dealing with the prophetic material in the Hebrew Bible, scholars explore the motifs, effects, and role of forced migration on prophetic literature. Students and scholars interested in current, thorough approaches to the issues and problems associated with the study of geographical displacement, social identity ethics, trauma studies, theological diversification, hermeneutical strat- egies in relation to the memory, and the effects of various exilic conditions will find a valuable resource with productive avenues for inquiry”— Provided by publisher ISBN 978-1-62837-051-5 (paper binding : alk. -

1 Context Overview 2 Outline of Ezekiel 26

Author: Ron Graham EEzzeekkiieell CChhaapptteerrss 2266,, 2277 aanndd 2288 —Outline and Notes 1 Context Overview Jerusalem has been under siege by Nebudchadnezzar king of Babylon, and finally the city has been ransacked and brought to ruin. Many Israelites were killed, many taken captive to Babylon, and some escaped. So Israel now consisted of the slaughtered in Jerusalem, the exiles in Babylon, and the fugitives among other nations. Ezekiel was among the exiles in Babylon who had been taken captive years earlier. He was appointed by God to watch over the Israelite captives and teach them by sharing his visions, preaching oracles from God, and performing symbolic acts. Not many paid heed to Ezekiel. King Nebuchadnezzar was attacking other nations besides Judah, and other cities besides Jerusalem. Prominent among these was the kingdom and city of Tyre. God promised that Tyre, because it had become corrupt, would be attacked by the Babylonians and by "many nations" and eventually be destroyed like Jerusalem. Ezekiel delivers God’s counsel to Tyre in a series of prophecies, laments, and oracles. 2 Outline of Ezekiel 26 11th YEAR (Ezekiel 26:1). Prophecy Against Tyre Jerusalem is in ruins and Judah is desolate. The coastal kingdom of Tyre thinks that opens the gate for Tyre to expand and profit. (Ezekiel 26:1-2). But God is against Tyre, and the kingdom will eventually suffer the same ruin as Jerusalem. This will result from "many nations" making wave after wave of assault (Ezekiel 26:3-6). Nebuchadnezzar will Attack Tyre Babylon will be the first of the nations to attack Tyre.