Manual Karate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

玄同 Kokusai Budoin, IMAF 2013 Gendo International Martial Arts Federation Newsletter No

国際武道院 国際武道連盟 玄同 Kokusai Budoin, IMAF 2013 Gendo International Martial Arts Federation Newsletter No. 2 The objectives of Kokusai Budoin, IMAF, include the expansion of interest in Japanese Martial Arts; the Upcoming Events establishment of communication, friendship, understanding and harmony among member chapters; the development of the minds and bodies of its members; and the promotion of global understanding 2013 Kokusai Budoin, IMAF and personal growth. European Congress Location: Budapest, Hungary 2013 Kokusai Budoin, IMAF All Japan Budo Exhibition Date: 18 - 20 October Tokyo Information & Reservation details pages 6 - 8 Hirokazu Kanazawa (right-side) receiving his Karatedo Meijin 10th Dan certicate from Kokusai Budoin, IMAF President Yasuhisa Tokugawa at the 35th All Japan Budo Exhibition reception. Contact: [email protected] 2013 Kokusai Budoin, IMAF HQ Autumn Seminar Location: Greater Tokyo Area Date: To Be Announced Contact: [email protected] Featured News 2013 Kokusai Budoin, IMAF All Japan Budo Exhibition Kokusai Budoin, IMAF Portal Site Largest Branch Country Sites International Representatives Multiple Languages, and more... http://kokusaibudoin.com 2013 Shizuya Sato Sensei Memorial Training Tokyo Cidra, Puerto Rico Held May 26th at the Ikegami Kaikan in Tokyo, the 35th All Japan Budo Exhibition featured 25 February 2013 leading Japanese and international practitioners from all Kokusai Budoin, IMAF divisions. Updates for Members Membership Renewals and more... Kokusai Budoin, IMAF sponsors numerous national, regional -

'Christian' Martial Arts

MY LIFE IN “THE WAY” by Gaylene Goodroad 1 My Life in “The Way” RENOUNCING “THE WAY” OF THE EAST “At the time of my conversion, I had also dedicated over 13 years of my life to the martial arts. Through the literal sweat of my brow, I had achieved not one, but two coveted black belts, promoting that year to second degree—Sensei Nidan. I had studied under some internationally recognized karate masters, and had accumulated a room full of trophies while Steve was stationed on the island of Oahu. “I had unwittingly become a teacher of Far Eastern mysticism, which is the source of all karate—despite the American claim to the contrary. I studied well and had been a follower of karate-do: “the way of the empty hand”. I had also taught others the way of karate, including a group of marines stationed at Pearl Harbor. I had led them and others along the same stray path of “spiritual enlightenment,” a destiny devoid of Christ.” ~ Paper Hearts, Author’s Testimony, pg. 13 AUTHOR’S NOTE: In 1992, I renounced both of my black belts, after discovering the sobering truth about my chosen vocation in light of my Christian faith. For the years since, I have grieved over the fact that I was a teacher of “the Way” to many dear souls—including children. Although I can never undo that grievous error, my prayer is that some may heed what I have written here. What you are about to read is a sobering examination of the martial arts— based on years of hands-on experience and training in karate-do—and an earnest study of the Scriptures. -

Santo Torre C.N. 7° Dan Technical Director of the C.S.K.S.Centro Studi Karate Shotokan Catania and Vittoria Born in Acicatena (Catania) 10/6/53

SANTO TORRE C.N. 7° DAN TECHNICAL DIRECTOR OF THE C.S.K.S.CENTRO STUDI KARATE SHOTOKAN CATANIA AND VITTORIA BORN IN ACICATENA (CATANIA) 10/6/53. HIGH SCHOOL DIPLOMA AND BACHELOR'S DEGREE IN SPORTS SCIENCE SANTO TORRE EX COMPETITOR AND MEMBER OF THE ITALIAN NATIONAL TEAM (FESIKA) ITALIAN KARATE SPORTS FEDERATION. FROM 1969 TO 1984 HE WALKED ALMOST ALL THE TATAMIS OF ITALY AND EUROPE, TAKING PART IN MANY NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS AND INDIVIDUAL TEAM GETTING EXCELLENT RESULTS, MAINLY KUMITE AGONIST, AND AFTERWARDS SPECIALIST IN KATA. SANTO TORRE IN 1967 HAD GONE TO MILAN TO STUDY KARATE UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF RENOWNED JAPANESE MASTER HIROSHI SHIRAI, THE MASTER WHO BROUGHT FAME TO THE OLD ITALIAN KARATE, SANTO TORRE HAS ALSO STUDIED KARATE WITH OTHER FAMOUS MASTERS SUCH AS NAKAIAMA, KEINOSUKE ENOEDA MASATOSHI, TAIJI KASE, KATSUMIRO, TSUIAMA, ETC. NAGAMINE SHOGI. SANTO TORRE IN 1977 RETURNED BACK TO HIS HOMELAND, SICILY, WHERE CATANIA TOGETHER WITH HIS WIFE ELEONORA FOUNDED THE FIRST ASSOCIATION OF THE CENTRO STUDI C.S.K.S. KARATE SHOTOKAN KARATE, THEN HE WAS FORCED TO TEACH "KARATE DO" AND AS A RESULT HE HAD TO ABANDON THE COMPETITION, CONTINUING ALSO TO TRAVEL FROM CATANIA TO MILAN, WHERE HIS TEACHER LIVES; IN ORDER TO FURTHER REFINE HIS "KARATE DO" AND STAY ABREAST , AS WELL AS PARTICIPATE IN SOME INTERNATIONAL TOURNAMENT . DEGREES ACQUIRED IN 1970 PASSES C.N. 1° DAN ---- IN 1973 C.N. 2° DAN---- IN 1976 C.N. 3° DAN----4TH DAN IN 1980--- IN 1984 5° DAN IN 1990 6 ° DAN. AND IN 2001 WAS AWARDED THE 7TH DAN BY MASTER JAPANESE TATSUNO KUNEO THE 7TH DAN, HE WAS RECOGNIZED IN 2003 FOR SPECIAL MERITS FROM THE FEDERATION F.I.J.L.K.A. -

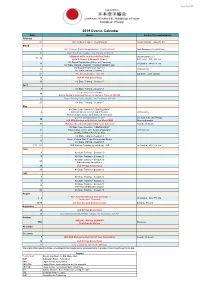

2019 Events Calendar

Issue: April 2019 2019 Events Calendar Date Event Contact Person/Location February 24 VKL Melbourne Open – Keysborough Rosanna Kassis – 0402 278 531 March 3 ** AKF Victorian State Championships – Wantirna South ** Aash Dickinson – 0488 020 822 11 Labour Day Public Holiday - No Training at JKA NP SEMINAR WITH JKA HQ INSTRUCTORS JKA SKC Melbourne 11 - 12 Naka T. Sensei & Okuma K. Sensei Keith Geyer - 0407 886 764 KV Squad Registration (Kata)– VU Footscray 16 Ian Basckin – 0410 778 510 KV State Training – Session 1 Kumite Evaluation Day KV Squad Registration (Kumite) 23 VU Footscray KV State Training – Session 2 24 VKL Shotokan Open – Box Hill Edji Zenel – 0438 440 555 29 JKA NP Kyu Grade Exam 30 KV State Training – Session 3 April 6 KV State Training – Session 4 Good Friday Public Holiday 19 Senior Grade training will be on, no General Class at JKA NP 22 Easter Monday Public Holiday - No Training at JKA NP 27 KV State Training – Session 5 May KV State Team Selection *COMPULSORY* 4 Kata (Children 8 to 13 yr. old & Teams) VU Footscray Kumite (Cadet, Junior, U21, Senior & Veterans) Queen's Birthday Public Holiday 5 to 8 pm at the JKA NP Dojo 10 JKA KDA Seminar with Shihan Jim Wood MBE Open to all grades 11 JKA Aus. Oceania Championship Team Selection Rowville, Melbourne KV State Team Selection *COMPULSORY* 11 Kata (Cadet, Junior, U21, Senior & Veterans) VU Footscray Kumite (Children 9 to 13 yr. old) 18 KV State Training – Session 8 Karate Victoria State Team Presentation Dinner 25 KV State Training – Session 9 31/5 – 2/6 AKF National Training -

Aikido Shihan Hiroshi Tada: the Budo Body, Part 1 Written by Christopher Li Aikidosangenkai.Org

http://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/aikido-shihan-hiroshi-tada-budo-body-part-1/ Aikido Shihan Hiroshi Tada: The Budo Body, Part 1 Written by Christopher Li aikidosangenkai.org Aikido Shihan Hiroshi Tada: The Budo Body, Part 1 Posted on Sunday, August 12th, 2012 at 2:35 pm. Tatsuro Uchida interviews Hiroshi Tada Sensei These three Budo “tips” came from Hiroshi Tada in a lecture that he gave in Italy in 2002: 1) An Aikidoka should be able to consistently cut down an opponent with the first blow. This it the true Budo aspect of Aikido. It is precisely because we are confident that we will always able to do this. This confidence gives us two things, our strength and the ability to choose a less deadly outcome, both of which we should have as a prerequisite to our training. Hiroshi Tada Sensei 2) When you look at your opponent, he becomes the center of your Aikido, causing you to stop. When you practice, observe where your eyes tend to look. You should be the center of your movement, so when you move, you should see all around you. The question is how far can you see around you? half a meter? 1 meter? 3 meters? 5 meters? As far as your eyes can see, that is the sphere of your control. Once someone enters the sphere of your control, he is drawn to you as the center of that sphere. When O-Sensei would hold a session, one would notice that it was hard to see where he was looking, as if his eyesight was looking outside of the dojo. -

D. Miguel Ángel Gómez Martínez, 6º Dan De Karate De La REAL FEDERACION ESPAÑOLA DE KARATE, Y Director Del CLUB YOSHITAKA

KARATE-DO, APUNTES CONTEMPORANEOS JOSE VTE. MONTANER MARTINEZ 2013 KARATE-DO, APUNTES CONTEMPORANEOS D. Miguel Ángel Gómez Martínez, 6º Dan de Karate de la REAL FEDERACION ESPAÑOLA DE KARATE, y Director del CLUB YOSHITAKA. Nº de Registro: 195 CERTIFICA: Que la presente tesina ha sido realizada, íntegramente, por José Vicente Montaner Martínez, lo cual firmo y rubrico, para los efectos oportunos. Firmado.- Miguel Ángel Gómez Martínez JOSE VTE. MONTANER MARTINEZ 2013 KARATE-DO, APUNTES CONTEMPORANEOS Esta tesina ha sido realizada íntegramente por José Vicente Montaner Martínez D.N.I. 22.634.343–C Cinturón negro 5º Dan de la REAL FEDERACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE KARATE Carné nº 7273 Nº de licencia KA-620 Firmado.- José Vicente Montaner Martínez. Cheste, 28 de Marzo de 2.013 JOSE VTE. MONTANER MARTINEZ 2013 KARATE-DO, APUNTES CONTEMPORANEOS AGRADECIMIENTOS Difícil momento el de los agradecimientos, no por lo que supone plasmarlos en el papel, sino porque por más que en éste escriba, dudo que pueda agradecer lo suficiente, a todas las personas a las cuales debo de referirme en este escrito. Mi primer agradecimiento se lo debo al karate, ya que por él estoy escribiendo estas líneas. Me siento afortunado por haber tenido la suerte de conocerlo, practicarlo y poder haber hecho de él mi estilo de vida. Los valores que en él se transmiten, y que teóricamente se deben de poner en funcionamiento desde el primer día de su práctica, son los que llevan a los karatecas a su más alto nivel también como personas. Son sin duda alguna, los principios de la vida, pero en el dojo (lugar donde se practican artes marciales) éstos se suelen inculcar un poco más. -

Cat Ogo De Productos Kamikaze Karategi

Katalog : Bücher (Deutstch) 1 Buch Kuatsu und Akupressur, Fritz Oblinger und Gerhard Kerschera, deutsch Buch Kuatsu und Akupressur, Fritz Oblinger und Bücher Gerhard Kerscher, deutsch. 14,8 x 21 cm. 240 Neuheiten Seiten. Kuatsu und Akupressur in den Kampfkünsten. Erste Hilfe für Budo, Sport und... (+ info) 32,90 € 1 31,63 € 2 Ref.: 002225000 BUCH GICHINS FAUST Aus den Gründerjahren des Buch Die Karate-Essenz. Das Handbuch, Fiore Shôtôkan Karate, Konno Bin, deutsch Tartaglia, deutsch Buch GICHINS FAUST - Aus den Gründerjahren des Buch Die Karate-Essenz. Das Handbuch, Fiore Shôtôkan Karate, Konno Bin, Dr. Wolfgang Herbert, Tartaglia, deutsch. 17 x 24 cm. 304 Seiten. 14,8 x 21 cm, 298 Seiten, deutsch. Eine Erzählung Insgesamt 386 Zeichnungen. Umschlag mit des japanischen Erfolgsautors Konno... (+ info) Einklapplaschen und partieller Lackierung. Fadenheftung. Übersichtliche... (+ info) 23,90 € 1 22,98 € 2 28,90 € 1 27,79 € 2 Ref.: 002208000 Ref.: 002192000 Buch Geschichte und Lehre des Karatedo, Heiko BUCH KANAZAWA Im Zeichen des Tigers, Hirokazu Bittmann, Deutsch KANAZAWA, deutsch Buch Geschichte und Lehre des Karatedo von Heiko Buch KANAZAWA Im Zeichen des Tigers - Eine Bittmann. deutsch, DIN A5, 264 Seiten. 2. Autobiographie, Hirokazu KANAZAWA, 18 x 26 cm, überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage des Buches 352 Seiten, deutsch. (Übersetzung: Dr. Wolfgang "Die Lehre des Karatedô" mit einem neuen Kapitel Herbert). Klimaneutral... (+ info) zur Geschichte des... (+ info) 26,38 € 1 25,37 € 2 33,50 € 1 32,21 € 2 Ref.: 000687000 Ref.: 001901000 Buch Die Form des Karate - Roman Westfehling, Buch Mein Erstes Karate-Buch, der Karate-Weg der deutsch Kinder, deutsch Buch Die Form des Karate - Kata als umfassendes Buch Mein Erstes Karate-Buch, der Karate-Weg der Übungskonzept, Roman Westfehling, deutsch. -

Student(Handbook(

Arizona(JKA 6326(N.(7th(Street,(Phoenix,(AZ(85012( Phone:(602?274?1136( www.arizonajka.org www.arizonakarate.com( ! [email protected]( ! Student(Handbook( ! ! What to Expect When You Start Training The Arizona JKA is a traditional Japanese Karate Dojo (school). Starting any new activity can be a little intimidating. This handbook explains many of the things you need to know, and our senior students will be happy to assist you and answer any questions you might have. You don’t have to go it alone! To ease your transition, here are some of the things you can expect when you start training at our Dojo: Class Times Allow plenty of time to change into your gi, or karate uniform. Men and women’s changing rooms and showers are provided. You should also allow time to stretch a little before class starts. Try to arrive 15 minutes before your class begins. If your work schedule does not allow you to arrive that early, explain your situation to one of the senior students. There is no limit to the number of classes you can attend each week, but we recommend training at least 3 times a week if at all possible, to gain the greatest benefit from your karate training. Morning Class: 11:00 a.m. to 12:00 noon Monday, Wednesday, Friday Adult class, where all belt levels are welcome. Afternoon Class: 5:30 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. Monday, Wednesday, Friday All ages and belt levels are welcome. This class has multiple instructors and is ideal for the beginning student. -

Hideo Yamamoto & Tatsuya Naka BEIM GASSHUKU & KATA-Spezial

Magazin des Deutschen JKA-Karate Bundes e.V. HEFT 01/2018 HIDEO YAMAMOTO & TATSUYA NAKA BEIM GASSHUKU & KATA-SPEZIAL • EINLADUNG ZUR ORDENTLICHEN MITGLIEDERVERSAMMLUNG DES DJKB • • AUSSCHREIBUNG DEUTSCHE MEISTERSCHAFT 2018 • KATA UND HÜFTE • • BERND HINSCHBERGER ZUM 70STEN GEBURTSTAG • GASSHUKU & KATA-SPEZIAL POSTER • ©Collage: demaex – Fotos: Sven Mikolajewicz Sven – Fotos: ©Collage: demaex EDITORIAL AKTUELLES BITTE BEACHTEN! Bei der Deutschen Meisterschaft am 09. Juni 2018 in Bochum gibt es bei den ONLINE-JAHRESMELDUNG Kumite- und Kata-Team Wettbewerben ab 18 Jahren keine Unterteilung in DER MITGLIEDER 2018 Junioren/Erwachsene +21 mehr. UNTER: In den Einzeldisziplinen starten die Athleten weiterhin in den Altersgruppen WWW.DJKB.COM/FORMULARE 18 - 20 und +21 Jahren. Seit 2017 können Dojos ihre Mitglieder für 2018 online melden. 43 M 3. Kyu - DAN 18 - 99 Kumite-Team Jiyu Kumite (Freikampf) 1. Möglichkeit: 44 W 3. Kyu - DAN 18 - 99 Kumite-Team Jiyu Kumite (Freikampf) Übernahme der Ist-Daten aus 2017, dann 45 M 3. Kyu - DAN 18 - 99 Kata-Team freie Wahl einzelne Mitglieder löschen oder auf in- 46 W 3. Kyu - DAN 18 - 99 Kata-Team freie Wahl aktiv setzen. Neue Mitglieder können später wieder manuell ergänzt werden. 2. Möglichkeit: In die „leere Tabelle“ eine aktuelle Ex- cel-Liste hochladen. INSTRUCTOR-LEHRGÄNGE 2015 - 2017 & DIE DOJOLEITER-TAGE 2015 & 2016 AUF DVD! Der DJKB bietet in Kooperation mit Axel Schmidt/Bad Lausick die Möglichkeit für Interessierte, DVDs der Instructor-Lehrgänge 2015 – 2017 und Dojoleiter-Tage LEHRGANGSAUSSCHREI- 2015 und 2016 für den Eigengebrauch zu erwerben. BUNGEN IM DJKB-MAGAZIN: Die DVDs beinhalten sowohl Bildmaterial als auch Videoclips der Lehrgänge. Lehrgangsausschreibungen, die bis Insbesondere die Workshop-Dokumentationen sind für interessierte Trainer/innen zum Redaktionsschluss auf der Home- sicher interessant. -

Keinosuke Enoeda Sensei

Beckie Challans Life of a Karate Master – Keinosuke Enoeda Sensei Born on July 4th, 1935, in Kyushu, South Japan, Keinosuke Enoeda was widely known as ‘Tora’ – or, the Tiger. Gaining this nickname, through his reputation and skill as a competitive and extremely successful Karateka. It is not surprising that Enoeda Sensei was so highly revered by his fellow martial artists. Sensei first started out as a martial artist at the age of seven, when he took up Judo, alongside other massively popular activities in Japan at the time; Kendo, and baseball. He proved to be very skilled, and the art came naturally to him, allowing him to achieve the grade of Nidan at the age of just sixteen, laying the foundations for his future life in the martial art world. Not long after achieving this grade, however, Enoeda Sensei found himself at a Karate demonstration, held at Takushoku University, and showcasing two of the main instructors of that group – Senseis Okazaki and Irea. He found himself to be inspired by what he saw that day, and upon enrolling on a degree in Economics, he joined the group, and began to train in Shotokan Karate. After just 2 years of tuition from instructors such as Okazaki and Irea, and even Sensei Gichin Funakoshi himself, Enoeda was awarded with his Shodan, the first of the eight dan grades he would achieve over his lifetime. A further 2 years saw him take on the role of Captain for the competition team associated with the university, which allowed him to enter a large number of competitions for the university, in particular within the kumite division of the JKA All-Japan Championships. -

Student Handbook

Student Handbook 1 Budo Shotokan Karate, LLC • 1401 3rd Ave • Longmont, CO 80501 • (720) 899‐8836 [email protected] http://www.budoshotokan.com Affiliated with the International Shotokan Karate Federation (ISKF) Introduction Welcome to Budo Shotokan Karate. New students are always welcome and we recognize that you are an essential and valuable part of our karate training group. We look forward to working with you and hope to see you thrive as we begin this journey together. Shotokan karate training helps increase physical fitness, confidence, improved motor skills, flexibility, speed, concentration, discipline and personal safety. Karate is practiced by young and old alike. Anyone can learn karate no matter what your age, gender and physical condition. Karate encompasses so much more than just physical training. The mental & spiritual benefits of karate training are endless and increases as you progress along this journey. Learning karate can be an extremely awkward experience at first. Not only are you exercising your body in ways that you have never done before, but it also encompasses mental & spiritual aspects that you may have not foreseen. Karate is deeply rooted in Eastern philosophies and with that comes a different way of thinking. Mutual respect for one another is of utmost importance. That being said, persistence and a positive attitude towards learning will help overcome this initial awkwardness. Below you will find some useful information that will attempt to answer the most commonly asked questions and the rules and etiquette of the dojo (training place). If you have questions, please do not hesitate to ask the Sensei (Teacher) or Sempai (Senior Student). -

ISKF Spotlight June 2019 V5R Final

International Shotokan Karate Federation June 2019 SPOTLIGHT To Preserve and Spread Traditional Japanese Karate through Exceptional Instruction Master Camp 2019 - Bringing You the Best Instructors in One Camp! Once again, Master Camp 2019 promises to deliver on the excitement and rigorous training of past camps. Hosting camp is Shihan Hiroyoshi Okazaki, 9th Dan and Chairman and Chief Instructor of the ISKF, and joining him is Master Miura, 9th Dan and Chief In The Instructor of SKI/Europe. Spotlight We are also excited to introduce two new instructors to Master Camp, Sensei A Question from Takechiyo Nemoto and Sensei Shihan Okazaki Ryozo Hirata. In 2017, Sensei Page 2 Nemoto and Sensei Hirata were appointed joint Assistant Instructors to Shihan Takahashi of ISKF/TSKF Australia. Master Camp Lectures Sensei Nemoto, 4th Dan, began training at age six in Chiba, Japan. In college Page 2 he joined the Aoyama Gakuin University Karate Club, training under the leadership of Takahashi Shihan. In 1996, he was elected as the team captain In Memoriam: and in 2013 he was appointed as coach of the karate team. His tournament Sensei Greer Golden accomplishments include 1st place in individual kumite at the JKF All Kanto Page 3 Regional University Tournament in 1996, and he was also part of the 1st place Kata and Kumite Teams at the JKA National Championship in the same year. Spotlight Interview: Sensei Hirata, 5th Dan, started training at the Kashii Dojo (JKA) in Fukuoka, Sensei Mark Tarrant Japan at the age of 10. At 13 he won 3rd place in Junior Individual Kata in JKA Page 6 World Championship Osaka, Japan.