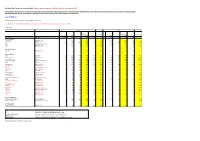

Food and Soft Drink Advertising Survey 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes About This Report

NRS Estimates of Average Issue Readership for latest 12 & 6 month periods Ending June 200 Media Release September 19th, 2005 For the first time, NRS is producing a set data for journalists and media commentators to help them identify and quantify changes in the survey’s readership estimates. These tables will now be updated every quarter, and will be available via email or via the NRS website (in the subscribers-only section) at www.nrs.co.uk. Notes About This Report This report shows NRS Average Issue Readership estimates sorted by publication group (daily newspapers, Sunday newspapers, general weekly magazines etc.) for two data periods, 12 months and 6 months. Virtually all publications are reported on the 12-month base*, but only those with a sufficient sample size are reported on the 6-month base. The first column is the estimate (in 000s) for the most recent data period, the second column the estimate for the equivalent period a year ago. The third and fourth columns show the difference in the estimates between those periods, expressed in 000s and as a plus or minus percentage change. It is important to note that – as with any other sample-based survey - NRS estimates are subject to sampling variation. If two independent samples of the population are interviewed – which is what NRS is doing each year – the estimates obtained from these samples may be different, but if the differences are relatively small, they may be due simply to sampling variation. Therefore, when making any period-on-period comparison, it is important to express it as a change in the readership estimate, rather than a change in the actual readership. -

ABC Consumer Magazine Concurrent Release - Dec 2007 This Page Is Intentionally Blank Section 1

December 2007 Industry agreed measurement CONSUMER MAGAZINES CONCURRENT RELEASE This page is intentionally blank Contents Section Contents Page No 01 ABC Top 100 Actively Purchased Magazines (UK/RoI) 05 02 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 09 03 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution (UK/RoI) 13 04 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Circulation/Distribution Increases/Decreases (UK/RoI) 17 05 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Actively Purchased Increases/Decreases (UK/RoI) 21 06 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Newstrade and Single Copy Sales (UK/RoI) 25 07 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Single Copy Subscription Sales (UK/RoI) 29 08 ABC Market Sectors - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 33 09 ABC Market Sectors - Percentage Change 37 10 ABC Trend Data - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution by title within Market Sector 41 11 ABC Market Sector Circulation/Distribution Analysis 61 12 ABC Publishers and their Publications 93 13 ABC Alphabetical Title Listing 115 14 ABC Group Certificates Ranked by Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 131 15 ABC Group Certificates and their Components 133 16 ABC Debut Titles 139 17 ABC Issue Variance Report 143 Notes Magazines Included in this Report Inclusion in this report is optional and includes those magazines which have submitted their circulation/distribution figures by the deadline. Circulation/Distribution In this report no distinction is made between Circulation and Distribution in tables which include a Total Average Net figure. Where the Monitored Free Distribution element of a title’s claimed certified copies is more than 80% of the Total Average Net, a Certificate of Distribution has been issued. -

Cosmopolitan UK Part 1

LOGIN JOIN FREE WEB SITE Search here TRY: : Hot Olympic athletes : Celeb fitness tips : LOVE & SEX FASHION HAIR & BEAUTY CELEBS BODY HOROSCOPES COSMO ON CAMPUS COMPS & OFFERS FORUMS MORE HOME / DIET & FITNESS Join us Here Going under the knife for the perfect bikini body 28 August 2012 by Cosmopolitan One journalist's life changed forever after she interviewed Kelly Osbourne for Cosmo. After discussing the star's own dramatic weight loss during the interview, Louise Barnett was inspired to go on her own weight loss mission and ditched seven stone. But saggy skin was preventing her from having her dream bikini body. Here, Louisa Barnett tells us about making the drastic decision to have plastic surgery and takes us through the lead up to landing on the surgeon's table Like 0 Tw eet 9 0 Email Print RSS Share Latest Forums View all My name is Louisa Barnett and I’m a 30-year-old entertainment journalist from London living and working Re: Books in LA. I recently lost seven stone after interviewing It's not a book but a funny and interesting blog... Kelly Osbourne for the cover of Cosmo on her Posted by Jjay198...-04 Sep 2012 07:12PM incredible weight loss. It was Kelly who inspired me to Re: Do you know a hot single man? I've heard the guy w ho w rites this blog is... embark on my own journey and in March 2011, I Posted by Jjay198...-04 Sep 2012 07:11PM started a strict diet and work-out regime. I went from Re: Stir fry? 17 stone to 10 stone in just over a year and was able Haha, clue's in the name! ;) The key to a stir.. -

HEARST PROPERTIES HUNGARY HEARST MAGAZINES UK Hearst Central Kft

HEARST PROPERTIES HUNGARY HEARST MAGAZINES UK Hearst Central Kft. (50% owned by Hearst) All About Soap ITALY Best Cosmopolitan NEWSPAPERS MAGAZINES Hearst Magazines Italia S.p.A. Country Living Albany Times Union (NY) H.M.C. Italia S.r.l. (49% owned by Hearst) Car and Driver ELLE Beaumont Enterprise (TX) Cosmopolitan JAPAN ELLE Decoration Connecticut Post (CT) Country Living Hearst Fujingaho Co., Ltd. Esquire Edwardsville Intelligencer (IL) Dr. Oz THE GOOD LIFE Greenwich Time (CT) KOREA Good Housekeeping ELLE Houston Chronicle (TX) Hearst JoongAng Y.H. (49.9% owned by Hearst) Harper’s BAZAAR ELLE DECOR House Beautiful Huron Daily Tribune (MI) MEXICO Laredo Morning Times (TX) Esquire Inside Soap Hearst Expansion S. de R.L. de C.V. Midland Daily News (MI) Food Network Magazine Men’s Health (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) (51% owned by Hearst) Midland Reporter-Telegram (TX) Good Housekeeping Prima Plainview Daily Herald (TX) Harper’s BAZAAR NETHERLANDS Real People San Antonio Express-News (TX) HGTV Magazine Hearst Magazines Netherlands B.V. Red San Francisco Chronicle (CA) House Beautiful Reveal The Advocate, Stamford (CT) NIGERIA Marie Claire Runner’s World (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) The News-Times, Danbury (CT) HMI Africa, LLC O, The Oprah Magazine Town & Country WEBSITES Popular Mechanics NORWAY Triathlete’s World Seattlepi.com Redbook HMI Digital, LLC (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) Road & Track POLAND Women’s Health WEEKLY NEWSPAPERS Seventeen Advertiser North (NY) Hearst-Marquard Publishing Sp.z.o.o. (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) Town & Country Advertiser South (NY) (50% owned by Hearst) VERANDA MAGAZINE DISTRIBUTION Ballston Spa/Malta Pennysaver (NY) Woman’s Day RUSSIA Condé Nast and National Magazine Canyon News (TX) OOO “Fashion Press” (50% owned by Hearst) Distributors Ltd. -

Beyond Arts and Media Soap Operas

ARTS AND MEDIA SOAP OPERAS Teacher’s notes 1 Teacher’s Level: Pre-intermediate (A2) Age: Teenagers Time: This lesson can be divided up in various ways to suit the time you have with your students. Below are two time options which you can choose from depending on the length of your class. However, these are just suggestions and there are plenty of other ways you could divide the lesson up. 90 minutes – Complete all activities in Hooked on soaps and Create a soap 60 minutes – Complete all activities in Hooked on soaps Note: Create a soap can be spread over more than one lesson. Summary: This lesson is divided into two sections: Hooked on soaps and Create a soap. In this lesson, students will: 1. read about soap operas; 2. look at a soap opera setting; 3. write a scene from a soap; 4. perform and record the scene. Key skills: reading, writing, speaking Subskills: history of soap operas, prepositions of place, writing a dialogue Materials: one copy of Hooked on soaps and Create a soap per student HOOKED ON SOAPS and encourage the students to explain what they have read to the rest of the class. Are they surprised by 1. Ask students this question: anything they read? What do Orlando Bloom, Kylie Minogue, Demi Moore, Key: 1. g; 2. l; 3. c; 4. a; 5. h; 6. j; 7. f; 8. d; 9. i; 10. k; Jude Law, Meg Ryan, Kate Winslet and Robin Wright 11. e; 12. b Penn all have in common? 5. Soaps often take place on one street or in one If they say, They are all actors, tell them that is right but area of a town or city. -

Game On: Ways of Using Games to Engage Learners in Reading For

Game On: Ways of using digital games to engage learners in reading for pleasure October 2011 1 Contents Summary and key recommendations 3 1 Background 5 2 Recent research 8 3 A further review of games 13 4 Developing and testing two games 23 5 Observations from the think tank event 36 6 Recommendations 38 This report has been compiled by Genevieve Clarke and Michelle Treagust with thanks to colleagues at The Reading Agency, NIACE and PlayGen and also to students and tutors at Morley College, Transport for London, Brent Adult and Community Education Service and Park Future Family Learning Centre in Havant who took part in this project. Please contact [email protected] for further information. The Reading Agency has been funded by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills to undertake this study as part of its ongoing work to promote the use of reading for pleasure to engage, motivate and support adults with literacy needs. The Reading Agency Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road London EC1R 3GA tel: 0871 750 1207 email: [email protected] web: readingagency.org.uk 2 Summary and key recommendations This document reports on the project undertaken by The Reading Agency for the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) and NIACE between April and June 2011 which aimed to: help develop the Department’s thinking and plans to capitalise on the power of digital games; lay better groundwork to help the learning and skills sector harness the potential of games to engage and support people who are struggling with reading and writing and transform their perception of literacy and its relevance to their lives; and take The Reading Agency’s adult literacy development work with digital games to the next stage. -

NRS Oct16-Sep17 Fused with Comscore Sep2017 Data Are Strictly Embargoed Until 08:59 on Monday 18Th December 2017

NRS Oct16-Sep17 fused with comScore Sep2017 Data are strictly embargoed until 08:59 on Monday 18th December 2017 NRS datasets in 2017 are a blend of NRS and AMP print data. Due to the different methodologies, the PAMCo Board have mandated that NRS and AMP data should not be compared for commercial or marketing purposes. This means that the net print and PC figures in this report should not be compared with previous periods of NRS PADD data. Base: GB Adults 15+ Only PC websites with comScore sample of 40+ are included NB Entries are shown in red where the website is not specific to the one print title but a portal or website serving more than one title. Magazines Monthly Weekly Net Print + PC Increase with Net Print + PC Increase with Frequency Print PC Total (Net) PC Only PC Print PC Total (Net) PC Only PC Print Title(s) Website(s) (Print) 000s 000s 000s 000s % 000s 000s 000s 000s % Womens Weekly Take a Break takeabreak.co.uk W 2840 39 2878 38 +1.3 1481 20 1501 20 +1.3 OK! ok.co.uk W 2516 542 3027 511 +20.3 934 181 1111 176 +18.9 Hello! HELLOMAGAZINE.COM* W 2346 223 2558 211 +9.0 839 97 933 94 +11.2 Now celebsnow.co.uk W 639 80 718 79 +12.3 226 33 259 33 +14.4 Womens Fortnightly Soaplife whatsontv.co.uk F 377 59 436 59 +15.8 166 29 194 29 +17.2 Womens Monthly Tesco tesco.com M 5150 3498 8257 3107 +60.3 1633 1280 2868 1235 +75.6 Waitrose Food waitrose.com M 2799 441 3191 392 +14.0 929 164 1087 158 +17.0 Asda Good Living asda.com M 1384 2067 3404 2020 +145.9 400 769 1165 764 +190.8 Good Housekeeping goodhousekeeping.co.uk M 1310 239 1536 -

Alma Plaza Is Coming — Almost Page 3

Palo 6°Ê888]Ê ÕLiÀÊ£ÇÊUÊ>Õ>ÀÞÊÎä]ÊÓääÊN xäZ Alto Alma Plaza is coming — almost Page 3 www.PaloAltoOnline.com Unsung pioneers of high tech African-American technologists lauded in Palo Alto page 16 Movies 26 Eating Out 28 Crossword/Sudoku 51 NArts Filmmaker explores Parkinson’s disease Page 21 NSports Quick action saves referee’s life Page 31 NHome & Real Estate Volunteers help Palo Alto go green Page 37 COUPONCOUPON SAVINGSSAVINGS 0'' OFF ANY BOZPOFJUFN t 4XJNTVJUT PURCHASE t 4BOEBMT t 4IPFT $ t 5PZT OF Expires 2/28/09 $25 .VDI.PSF Not/PUWBMJEXJUIBOZPUIFSPGGFSTPSEJTDPVOUT valid with any other offers of discounts onePOFQFSDVTUPNFS FYQJSFT per customer. Expires10/31/08 2/28/09 5 Not valid on XOOTR Scooters or trampolines. OR MORE Not valid on XOOTR Scooters Expires 2/28/09 875 Alma Street (Corner of Alma & Channing) 8BWFSMFZ4Ut 1BMP"MUP Downtown Palo Alto (650) 327-7222 Mon-Fri 7:30 am-8 pm, UPZBOETQPSUDPN Sat & Sun 8 am-6 pm "MTPBWBJMBCMFPOMJOF6TFDPVQPODPEF Best Chinese Cuisine Since 1956 FREE DINNER MANICURE AND 1700 Embarcadero, Palo Alto Buy 1 dinner entree & 856-7700 receive 2nd entree of equal or lesser value 1/2FREE. OFF SPA PEDICURE Must present coupon, LUNCH limit 2 coupons per table. $ (Includes Dim Sum on Carts) (Maximum Discount $15.00) ExpiresExpires 2/28/05 2/28/09 22 Not valid on FRI or SAT (reg. $37) DINNER Darbar 15% OFF (Maximum Discount $15.00) FINE INDIAN CUISINE ALL TAKE-OUT WAXING Largest Indian Buffet in Downtown P.A % Take-out & Catering Available DELIVERY BodyKneads SPA+SALON (Minimum $30.00) 129 Lytton Ave., Palo Alto 810 San Antonio Rd., Palo Alto (650) 852-0546 Not valid on private room dining. -

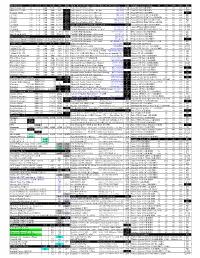

PC Zone Hardware Price List

Intel Processor LGA Core/T Ghz Cache FSB RM Turtle Beach Headset - PS3/ X-Box 360/ PC Gaming RM Graphic Card - Nvidia SP BIT CORE RAM RM Intel Celeron 430 775 1 / 1 1.80 512K 800 115 Turtle Beach EarForce Z2 TBS-2052 199 Asus GT 430 1GB DDR3 128 700 1600 279 Dual Core E5700 775 2 / 2 3.00 2MB 800 175 Turtle Beach EarForce PX21 - Wirless TBS-2130 319 Asus GT 440 1GB DDR5 128 822 3200 329 Pentium G620 1155 2 / 2 2.60 3MB 4.8(GT/s) 190 Turtle Beach EarForce P11 - Wireless TBS-2137 229 Asus GTX 450 1GB DDR5 128 810 3608 439 i3 2100 1155 2 / 4 3.10 3MB 4.8(GT/s) 350 Turtle Beach EarForce XL1 - Wireless TBS-2151 179 Asus GTX 550 Ti DC 1GB DDR5 192 910 4104 559 i5 2320 1155 4 / 4 3.00 6MB 4.8(GT/s) 550 Turtle Beach EarForce PX3 - Wireless TBS-2242 549 Asus GTX 550 Ti DC Top 1GB DDR5 192 975 4104 599 i5 2400 1155 4 / 4 3.10 6MB 4.8(GT/s) 575 Turtle Beach EarForce Charlie Z6A-5.1 TBS-4216-01 599 Asus GTX 560 DCII OC/2DI/1GD5 256 850 4200 745 i5 2500 1155 4 / 4 3.30 6MB 4.8(GT/s) 625 Turtle Beach EarForce PX3 - Wireless TBS-4242-01 759 Asus GTX 560 Ti DC II Top 1GB DDR5 256 900 4200 929 i5 2500K 1155 4 / 4 3.30 6MB 4.8(GT/s) 655 MP3/MP4/E-Book/MID/Bluetooth Devices RM Asus GTX 570 2DI 1280MB DDR5 320 742 3800 1289 i7 2600 1155 4 / 8 3.40 8MB 4.8(GT/s) 900 Car FM Modulator for Iphone/Ipod MP3-D8-868 69 Asus GTX 580/2DI/1536MD5 384 772 4008 1799 i7 2600K 1155 4 / 8 3.40 8MB 4.8(GT/s) 965 Car FM Modulator for Blackberry/HTC MP3-D8-869 69 Asus MATRIX GTX580P/2DIS/1536MD5 384 772 4008 1999 Core i7 960 1366 4 / 8 3.20 8MB 4.8(GT/s) 955 Car MP3 FM Modulator -

NRS Readership Estimates - General Magazines AIR - Latest 12 Months: January - December 2011

NRS Readership Estimates - General Magazines AIR - Latest 12 Months: January - December 2011 Adults Men Women Total ABC1 C2DE 15-44 45+ Total Total UNWEIGHTED SAMPLE 37039 21838 15201 14997 22042 16316 20723 EST.POPULATION 15+ (000s) 50239 27180 23059 24421 25818 24529 25710 (000s) % (000s) % (000s) % (000s) % (000s) % (000s) % (000s) % General Weekly Magazines What's on TV H 3325 6.6 1225 4.5 2100 9.1 1732 7.1 1593 6.2 1154 4.7 2172 8.4 Radio Times H 2227 4.4 1639 6.0 588 2.6 574 2.4 1653 6.4 1064 4.3 1162 4.5 TV Choice H 1984 3.9 741 2.7 1243 5.4 808 3.3 1177 4.6 687 2.8 1297 5.0 TV Times H 1427 2.8 589 2.2 837 3.6 648 2.7 779 3.0 580 2.4 847 3.3 Auto Trader H 1090 2.2 529 1.9 561 2.4 830 3.4 260 1.0 853 3.5 236 0.9 The Economist H 603 1.2 558 2.1 45 0.2 432 1.8 171 0.7 435 1.8 168 0.7 Nuts Y 552 1.1 230 0.8 322 1.4 493 2.0 59 0.2 494 2.0 58 0.2 The Big Issue H 504 1.0 354 1.3 150 0.7 237 1.0 268 1.0 246 1.0 258 1.0 TV & Satellite Week Y 453 0.9 200 0.7 253 1.1 199 0.8 254 1.0 228 0.9 225 0.9 TV Easy Y 446 0.9 164 0.6 282 1.2 213 0.9 232 0.9 131 0.5 314 1.2 Total TV Guide Y 438 0.9 181 0.7 257 1.1 216 0.9 222 0.9 183 0.7 255 1.0 New Scientist Y 404 0.8 347 1.3 57 0.2 248 1.0 156 0.6 255 1.0 150 0.6 Motorcycle News Y 381 0.8 173 0.6 208 0.9 209 0.9 173 0.7 303 1.2 79 0.3 The TES/Times Ed Sup Y 378 0.8 345 1.3 33 0.1 208 0.9 170 0.7 160 0.7 218 0.8 Kerrang! Y 360 0.7 189 0.7 171 0.7 321 1.3 39 0.1 222 0.9 137 0.5 The Week Y 357 0.7 313 1.2 45 0.2 141 0.6 216 0.8 169 0.7 188 0.7 Zoo Y 340 0.7 149 0.5 191 0.8 311 1.3 29 0.1 311 1.3 30 0.1 -

Future Publishing Statement for IPSO – April 2016

Future Publishing Statement for IPSO – April 2016 About Future Future plc is an international publishing and media group, and a leading digital company. Celebrating over 30 years in business, Future was founded in 1985 with one magazine – we now create over 200 print publications, apps, websites and events through operations in the UK, US and Australia. The company employs approximately 500 employees. Future’s leadership structure is outlined in Appendix C (the structure has changed slightly since our last statement in December 2015). Our portfolio covers consumer technology, games/entertainment, music, creative/design and photography. 48 million users globally access Future’s digital sites each month, we have over 200,000 digital subscriptions worldwide, and a combined social media audience of 20+ million followers (a list of our titles/products can be found under Appendix A). For the purpose of this statement, Future’s ‘responsible person’ is Nial Ferguson, Content Director, Media. Future’s editorial standards Through our expertise in five portfolios, Future produces engaging, informative and entertaining content to a high standard. The business is driven by a core strategy - ‘Content that Connects’ - that has been in place since 2014 (see Appendix B). This puts content at the heart of what we do, and is an approach we reiterate through staff communication. In creating content that connects, Future takes all reasonable and appropriate steps to verify what we publish. Such steps include double sourcing where necessary, and rigorous scrutiny of information and sources to ensure the accuracy of the articles we publish. Editorial process for contentious issues involves second reading by editorial. -

Anticipated Acquisition by Future Plc of Miura (Holdings) Limited

Anticipated acquisition by Future plc of Miura (Holdings) Limited Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition ME/6624/16 The CMA’s decision on reference under section 33(1)of the Enterprise Act 2002 given on 7 October 2016. Full text of the decision published on 14 November 2016. Please note that [] indicates figures or text which have been deleted or replaced in ranges at the request of the parties for reasons of commercial confidentiality. CONTENTS Page SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 2 ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................................... 4 Parties ................................................................................................................... 4 Transaction ........................................................................................................... 4 Jurisdiction ............................................................................................................ 4 Counterfactual....................................................................................................... 5 Overlap between the Parties ................................................................................. 6 Background ........................................................................................................... 7 Magazines – two-sided market .......................................................................