Gone to Seek a Fortune in North Carolina: the Failed Scottish Highland Emigration of 1884

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resb~Teri~N and MONTHLY RECORD

free ~resb~teri~n And MONTHLY RECORD. PEBRUAR Y, I92..I. No. 10. "lRome :Jl3ebin~ Sinn jfein/', T H~S is the title of an ex~ellen~ booklet on,the Ir~sh troub~e . by Mr. John A., Kenslt, London.* 1\:lr. Kenslt, who IS well known as a witness for Protestant 'truth, has gathered together all the principal facts of recent times which gO't0 prove that the representatives of the Roman Church are backing the Sinn Fein movement, and he has presented these facts in clear, brief, compact form in this little volume. The type is first-rate, and anumber of vivid pictorial illustrations are given that enhance the value of the publication and drive home its argument.' -We would like to see a copy of it in every'home in the Church, for although the most of our people have no dubiety as to the religious source of the happenints in Ireland, we believe there are still a few who think that" the land question" and questions of civil government are the chief causes of the Irish revolt. Now, whilst making all allo'wance for elements of discontent under civil, g~vernment~these, indeed, are· liable to emerge (fallen human nature being what it is) under any administration, no matter how good-we hold that in the present case, the largely prevailing cause is the religious 0lle-the determined efforts of the Roman Church to secure universal, supremacy, 'and its undying antagonism to Protestants and Protestant truth. Mr. Kensit, after touching, in his first chapter, on "priestcraft" as a root-cause of the' trouble-witnes'sed to even by Roman Catholic authorities-procee'ds to notice, in his second chapter, Romanism as a political conspiracy. -

Save Pdf (0.17

6.hB Oslrai isc Srtrmilrgt*t LXIV ORII,I,IA, MAY, r93z No. 5 CHARLES JAMES STEWART ,BtrTHUNE, M.A., D.C.L. Entomologists ancl other friends throughout Canada were grieved to hear of the death on April rSth of Dr. c. J. S. Bethune. Although Dr. Bethune was in his 94th year he had retained unimpaired throughout the years that keen mind r,vhich was the delight of all who knew him. The end was quite sud- den. Charles James Stewart Bethune was born on his maternal grandfather's farm in west Flamboro Torvnship, Upper canada, on August rzth, 1838. He was the son of the Rev. Alexander Neil Bethune, second Bishop of 'I'oronto, whose father, the Rev. John Bethune, came from Skye to North Carolina in 1774 and ministered to a Loyalist regiment during the revolutionary \Mar. After corning to Canada with the Loyalists the Rev. John ,Bethune opened the first Presbyterian Church in Montreal. His sons, however, attendecl the Rev. John Strachan's Anglican Church school ancl were all confirrnecl in the Church of England. Dr. c- J. S. Bethune had a distinguished career in the church, in edu- cation and in entomology. He graduated from Trinity.college in rg59, at the age of zr with first class honours in classics and mathematics. He received his n4.A. clegree in 186r and the degree of D.C.L. in 1883. After spending nine years in the Anglican priesthood he became heacl- master of rrinity college School, Port lrope, in r87o. He remained in this position until 1899. -

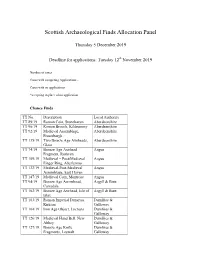

Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel

Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel Thursday 5 December 2019 Deadline for applications: Tuesday 12th November 2019 Number of cases – Cases with competing Applications - Cases with no applications – *accepting in place of no application Chance Finds TT No. Description Local Authority TT 89/19 Roman Coin, Stonehaven Aberdeenshire TT 90/19 Roman Brooch, Kildrummy Aberdeenshire TT 92/19 Medieval Assemblage, Aberdeenshire Fraserburgh TT 135/19 Two Bronze Age Axeheads, Aberdeenshire Glass TT 74/19 Bronze Age Axehead Angus Fragment, Ruthven TT 109/19 Medieval – Post-Medieval Angus Finger Ring, Aberlemno TT 132/19 Medieval-Post-Medieval Angus Assemblage, East Haven TT 147/19 Medieval Coin, Montrose Angus TT 94/19 Bronze Age Arrowhead, Argyll & Bute Carradale TT 102/19 Bronze Age Axehead, Isle of Argyll & Bute Islay TT 103/19 Roman Imperial Denarius, Dumfries & Kirkton Galloway TT 104/19 Iron Age Object, Lochans Dumfries & Galloway TT 126/19 Medieval Hand Bell, New Dumfries & Abbey Galloway TT 127/19 Bronze Age Knife Dumfries & Fragments, Leswalt Galloway TT 146/19 Iron Age/Roman Brooch, Falkirk Stenhousemuir TT 79/19 Medieval Mount, Newburgh Fife TT 81/19 Late Bronze Age Socketed Fife Gouge, Aberdour TT 99/19 Early Medieval Coin, Fife Lindores TT 100/19 Medieval Harness Pendant, Fife St Andrews TT 101/19 Late Medieval/Post-Medieval Fife Seal Matrix, St Andrews TT 111/19 Iron Age Button and Loop Fife Fastener, Kingsbarns TT 128/19 Bronze Age Spearhead Fife Fragment, Lindores TT 112/19 Medieval Harness Pendant, Highland Muir of Ord TT -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

T1mj-~ Ak~Jjs Mary-Anne Nicholls (Mrs.) Archivistlrecords Officer

Mission: To worship God and pro- claim Jesus Christ in the power of the Holy Spirit and to embody - in word and action - God's reconciling love, justice, compassion and liberation - Diocese of Toronto through which knowledge of God's Anglican Church of Canada reign is extended. April 22, 1997 /l'Js, Mi-gs Eunice Streeter Fwiher to our telephone conversation of April 17, 1997 enclosed please find the baptism records of the three Stutt girls as requested. They were located in the early parish records 0[31. Peter's, Cobourg. Interestingly, AN. Bethune was the officiant at all three and I have included a couple ofbriefbiographicaJ notes about him for your information. Yours sincerely, t1Mj-~ Ak~JJs Mary-Anne Nicholls (Mrs.) ArchivistlRecords Officer THE INCORPORATED SYNOD OF THE DIOCESE OF 1QRQ.NTO 135 ADELAIDE ST. E .• TORONTO· ONTARIO· M5C 1L8 • (416) 363-6021 t 1-800-6_~.!.:3: .1(Fax) 363 7678 . / The Right Reverenc 1867-J anuary-N o\'ember- of Lord Bishop of If67-1879-Lord Bi~: 18bo--Born Thursdar, 28tl Educated at tile Gr: 18.+7-D.0. (honoris (flU, 1857-D.C.L. (honoris Cflll 1823-0rdained Deacon in hec (J. l\Iountain . August, at the Ca: 182.j.-Ordained Priest in tl (J. l\Iountain). Church of the H, 1823'1~27-lncumbent of I 1827-1867-Rector of Cob( 1830-1867-Cbplain to th 18.j.I· 18.j.6- President. Tht' 18.j.7-1P67-Arcl~deacon of' 1866-Elrcted Coadjutor H= and with right of i her. hy the Synod! Onto . -

2013 Individual Results Highland Cross 2013 Individual Prizes

Highland Cross 2013 Individual Results Highland Cross 2013 Individual Prizes 1 Joe Symonds Inverness 03:16:55 First - Gent Joe Symonds Inverness 03:16:55 2 Ewan McCarthy Kingussie 03:34:15 First - Lady Claire Gordon Bathgate 04:01:40 3 Gordon Lennox Invergordon 03:35:04 First - Over 50 Gent David Oliphant Stirling 04:03:10 4 Stewart Whitlie Edinburgh 03:40:21 First - Over 50 Lady Marion Nicolson Inverness 04:55:09 5 Dan Gay Edinburgh 03:41:33 First - Over 60 Alex Brett Dingwall 04:40:51 6 Alan Semple Aberdeen 03:42:54 First - Superveteran Gent Adrian Davis Dunkeld 03:46:07 7 Michael O'Donnell Inverness 03:46:06 First - Superveteran Lady Mary Johnson Dingwall 04:37:14 8 Adrian Davis Dunkeld 03:46:07 First - Veteran Gent Stewart Whitlie Edinburgh 03:40:21 9 David Rodgers Fort William 03:46:15 First - Veteran Lady Lorna Stanger Thurso 04:23:16 10 Andrew MacRae Inverness 03:46:51 Mark Hamilton Memorial Trophy Iain MacDonald Dingwall 04:47:49 11 Graham Bee Elgin 03:47:01 Special Endeavour Trophy Roddy Main Inverness 12 Paul Miller Beauly 03:50:04 13 Anthony Lawther Kingussie 03:50:06 Highland Cross 2013 Team Prizes 14 Gary MacDonald Kinlochleven 03:58:22 15 Richard Lonnen Dingwall 03:58:29 First - Open Team Ken's Team 16 Steven McIntyre Inverness 04:00:40 Second - Open Team Against the Odds 17 Claire Gordon Bathgate 04:01:40 Third - Open Team Stirling Triers 18 Mike Legget Edinburgh 04:01:52 First - Overall Gents Team Looking Good, Looking Skinny 19 Jamie Paterson Dingwall 04:01:53 First - Overall Ladies Team Cross Land High 20 David Oliphant -

1 Remembering Montreal As a Site Of

1 Remembering Montreal as a Site of Transatlantic Slavery Charmaine A. Nelson Having lived in Montreal for many years, I often visited the historic neighbourhood of Old Montreal. As a scholar who studies Transatlantic Slavery, I found it to be full of ghosts. Old Montreal was Montreal at one time; the part of the city that was first settled by the French starting in the sixteenth century. In 1688 the colonial administrator Jean-Baptiste de Lagny (Sieur des Bringandières) petitioned the governor, Jacques-Réné de Brisay (Marquis de Denonville), to appeal to France for slaves.1 Already established trade routes between New France and several French-held Caribbean islands were cited as evidence of the feasibility of transportation. By the early eighteenth century, slavery continued to grow slowly to service the demand for domestics and field hands of the wealthier classes.2 By 1663, an aggressive new era of colony-building had ensued under King Louis XIV. Although hesitant about the ability of Africans to survive in the Canadian winters, the King was persuaded when local politicians extolled the success of slavery in New England as indicative of the resilience and adaptability of the African population. He gave his assent on 1 May 1689.3 Slavery in New France included the enslavement of people of African and Indigenous descent, a practice that the British continued after conquest with the renaming of the region as Quebec. Transatlantic Slavery transpired over the course of 400 years from the 1400’s to the 1800’s. The standard focus on the tropical or semi-tropical regions, has resulted in a fixation on mono-crop plantation economies where year-round agriculture resulted in the cultivation and exportation of crops like coffee, cotton, and sugar cane. -

Your Detailed Itinerary Scotland Will Bring You to the A96 to the North- Its Prehistory, Including the Standing This Is the ‘Outdoor Capital’ of the UK

Classic Scotland Classic Your Detailed Itinerary Scotland will bring you to the A96 to the north- its prehistory, including the Standing This is the ‘outdoor capital’ of the UK. east. At Keith, you can enjoy a typical Stones at Calanais, a setting of great Nearby Nevis Range, for example, is a Day 1 distillery of the area, Strathisla. presence and mystery which draws ski centre in winter, while, without Day 13 From Jedburgh, with its abbey visitor many to puzzle over its meaning. snow, it has Britain’s longest downhill Glasgow, as Scotland’s largest city, centre, continue northbound to (Option here to stay for an extra day mountain bike track, from 2150 ft offers Scotland’s largest shopping experience the special Borders to explore the island.) Travel south to (655m), dropping 2000ft (610m) over choice, as well as museums, galleries, landscape of rolling hills and wooded Day 4/5 Tarbert in Harris for the ferry to Uig almost 2 miles (3km). It’s fierce and culture, nightlife, pubs and friendly river valley. Then continue to Go west to join the A9 at Inverness in Skye. demanding but there are plenty of locals. Scotland’s capital, Edinburgh, with its for the journey north to Scrabster, other gentler forest trails nearby. Fort choice of cultural and historic ferryport for Orkney. From Stromness, William also offers what is arguably attractions. Explore the Old Town, the Stone Age site of Skara Brae lies Scotland’s most scenic rail journey, the city’s historic heart, with its quaint north, on the island’s west coast. -

![Inverness County Directory for 1887[-1920.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1473/inverness-county-directory-for-1887-1920-541473.webp)

Inverness County Directory for 1887[-1920.]

INVERNE COUNTY DIRECTORY 899 PRICE ONE SHII.I-ING. COAL. A" I i H .J.A 2 Lomhara ^ai-eei. UNlfERNESS ^^OCKB XSEND \V It 'lout ^'OAL produced .^mmmmmmmm ESTABLISHED 1852. THE LANCASHIRE INSUBANCE COY. (FIRE, IIFE, AND EMPLOYERS' LIABILITY). 0£itpi±a.l, THf-eo IVIiliion® Sterling: Chief Offices EXCHANGE STREET, MANCHESTER Branch Office in Inverness— LANCASHIRE INSURANCE BUILDINGS, QUEEN'S GATE. SCOTTISH BOARD- SiR Donald Matheson, K.C.B., Cliairinan, Hugh Brown, Esq. W. H. KiDBTON, Esq. David S. argfll, Esq. Sir J. King of ampsie, Bart., LL.D. Sir H arles Dalrymple, of Newhailes, Andrew Mackenzie, Esq. of Dahnore. Bart., M.P. Sir Kenneth J. Matheson of Loclialsh, Walter Duncan, Esq, Bart. Alexander Fraser, Esq., InA^eriiess. Alexander Ross, Esq., LL.D., Inverness. Sir George Macpherson-Gr-nt, Bart. Sir James A. Russell, LL.D., Edin- (London Board). burgh. James Keyden, Esq. Alexander Scott, Esq., J. P., Dundee- Gl(is(f<nv Office— Edinhuvfih Office— 133 West Georf/e Street, 12 Torh JiiMilings— WM. C. BANKIN, Re.s. Secy. G. SMEA TON GOOLD, JRes. Secy. FIRE DEPARTMENT Tlie progress made in the Fire Department of the Company has been very marked, and is the result of the promptitude Avith which Claims for loss or damage by Fiie have always been met. The utmost Security is afforded to Insurers by the amjjle apilal and large Reserve Fund, in addition to the annual Income from Premiums. Insurances are granted at M> derate Rates upon almost every description of Property. Seven Years' Policies are issued at a charge for Six Years only. -

Laws - by State

Laws - By State Bill Name Title Action Summary Subject AL S 32 Civics Tests for Students 04/25/2017 - This law requires students enrolled in a public institution in Alabama to take the Education Enacted civics portion of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services naturalization exam and score a 60 out of 100 prior to receiving a high school diploma. AL SJR 82 Bridge Designation 04/25/2017 - This resolution names a bridge after Johannes Whetstein and his family, who Resolutions Enacted immigrated to the U.S. in 1734, in order to recognize their contributions to the development of Autauga County in Alabama. AR H 1041 Application of Foreign 04/07/2017 - This law prohibits Arkansas institutions from applying foreign laws that violate Law Enforcement Law in Courts Enacted the Arkansas Constitution or the U.S. Constitution. AR H 1281 Human Services Division 04/05/2017 - This human services appropriations law includes funds for refugee resettlement. Budgets of County Operations Enacted AR H 1539 Naturalization Test 03/14/2017 - This law requires students enrolled in a public institution in Arkansas to take the Education Passage Requirement Enacted civics portion of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services naturalization exam and score a 60 out of 100 prior to receiving a high school diploma. AR S 531 School for Mathematics 03/28/2017 - This law exempts U.S. residents who attend The Arkansas School for Education and Arts Provisions Enacted Mathematics, Sciences, and the Arts from paying tuition, fees, and housing, while requiring international students to pay for tuition, fees, and housing. -

Scotland/Northern Ireland

Please send your reports, observations, and comments by Mail to: The PSV Circle, Unit 1R, Leroy House, 9 436 Essex Road, LONDON, N1 3QP by FAX to: 0870 051 9442 by email to: [email protected] SCOTLAND & NORTHERN IRELAND NEWS SHEET 850-9-333 NOVEMBER 2010 SCOTLAND MAJOR OPERATORS ARRIVA SCOTLAND WEST Limited (SW) (Arriva) Liveries c9/10: 2003 Arriva - 1417 (P807 DBS), 1441 (P831 KES). Subsequent histories 329 (R129 GNW), 330 (R130 GNW), 342 (R112 GNW), 350 (S350 PGA), 352 (S352 PGA), 353 (S353 PGA): Stafford Bus Centre, Cotes Heath (Q) 7/10 ex Arriva Northumbria (ND) 2661/57/60/2/9/3. 899 (C449 BKM, later LUI 5603): Beaverbus, Wigston (LE) 8/10 ex McDonald, Wigston (LE). BLUEBIRD BUSES Limited (SN) (Stagecoach) Vehicles in from Highland Country (SN) 52238 9/10 52238 M538 RSO Vo B10M-62 YV31M2F16SA042188 Pn 9412VUM2800 C51F 12/94 from Orkney Coaches (SN) 52429 9/10 52429 YSU 882 Vo B10M-62 YV31MA61XVC060874 Pn 9?12VUP8654 C50FT 5/98 (ex NFL 881, R872 RST) from Highland Country (SN) 53113 10/10 53113 SV 09 EGK Vo B12B YV3R8M92X9A134325 Pn 0912.3TMR8374 C49FLT 7/09 Vehicles re-registered 52137 K567 GSA Vo B10M-60 YV31MGC1XPA030781 Pn 9212VCM0824 to FSU 331 10/10 (ex 127 ASV, K567 GSA) 52141 K571 DFS Vo B10M-60 YV31MGC10PA030739 Pn 9212VCM0809 to FSU 797 10/10 54046 SV 08 GXL Vo B12BT YV3R8M9218A128248 Pn 0815TAR7877 to 448 GWL 10/10 Vehicle modifications 9/10: fitted LED destination displays - 22254 (GSU 950, ex V254 ESX), 22272 (X272 MTS) 10/10: fitted LED destination displays - 22802 (V802 DFV). -

TT Skye Summer from 25Th May 2015.Indd

n Portree Fiscavaig Broadford Elgol Armadale Kyleakin Kyle Of Lochalsh Dunvegan Uig Flodigarry Staffi Includes School buses in Skye Skye 51 52 54 55 56 57A 57C 58 59 152 155 158 164 60X times bus Information correct at time of print of time at correct Information From 25 May 2015 May 25 From Armadale Broadford Kyle of Lochalsh 51 MONDAY TO FRIDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) SATURDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) NSch Service No. 51 51 51 51 51 51A 51 51 Service No. 51 51 51A 51 51 NSch NSch NSch School Armadale Pier - - - - - 1430 - - Armadale Pier - - 1430 - - Holidays Only Sabhal Mor Ostaig - - - - - 1438 - - Sabhal Mor Ostaig - - 1433 - - Isle Oronsay Road End - - - - - 1446 - - Isle Oronsay Road End - - 1441 - - Drumfearn Road End - - - - - 1451 - - Drumfearn Road End - - 1446 - - Broadford Hospital Road End 0815 0940 1045 1210 1343 1625 1750 Broadford Hospital Road End 0940 1343 1625 1750 Kyleakin Youth Hostel 0830 0955 1100 1225 1358 1509 1640 1805 Kyleakin Youth Hostel 0955 1358 1504 1640 1805 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0835 1000 1105 1230 1403 1514 1645 1810 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 1000 1403 1509 1645 1810 NO SUNDAY SERVICE Kyle of Lochalsh Broadford Armadale 51 MONDAY TO FRIDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) SATURDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) NSch Service No. 51 51 51 51 51A 51 51 51 Service No. 51 51A 51 51 51 NSch NSch NSch NSch School Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0740 0850 1015 1138 1338 1405 1600 1720 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0910 1341 1405 1600 1720 Holidays Only Kyleakin Youth