Francia Bd. 41

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Faces of History. the Imagined Portraits of the Merovingian Kings at Versailles (1837-1842)

The faces of history. The imagined portraits of the Merovingian kings at Versailles (1837-1842) Margot Renard, University of Grenoble ‘One would expect people to remember the past and imagine the future. But in fact, when discoursing or writing about history, they imagine it in terms of their own experience, and when trying to gauge the future they cite supposed analogies from the past; till, by a double process of repeti- tion, they imagine the past and remember the future’. (Namier 1942, 70) The historian Christian Amalvi observes that during the first half of the nine- teenth century, most of the time history books presented a ‘succession of dyn- asties (Merovingians, Carolingians, Capetians), an endless row of reigns put end to end (those of the ‘rois fainéants’1 and of the last Carolingians especially), without any hierarchy, as a succession of fanciful portraits of monarchs, almost interchangeable’ (Amalvi 2006, 57). The Merovingian kings’ portraits, exhib- ited in the Museum of French History at the palace of Versailles, could be de- scribed similarly: they represent a succession of kings ‘put end to end’, with imagined ‘fanciful’ appearances, according to Amalvi. However, this vision dis- regards their significance for early nineteenth-century French society. Replac- ing these portraits in the broader context of contemporary history painting, they appear characteristic of a shift in historical apprehension. The French history painting had slowly drifted away from the great tradition established by Jacques-Louis David’s moralistic and heroic vision of ancient history. The 1820s saw a new formation of the historical genre led by Paul De- laroche's sentimental vision and attention to a realistic vision of history, restored to picturesqueness. -

Charlemagne Empire and Society

CHARLEMAGNE EMPIRE AND SOCIETY editedbyJoamta Story Manchester University Press Manchesterand New York disMhutcdexclusively in the USAby Polgrave Copyright ManchesterUniversity Press2005 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chaptersbelongs to their respectiveauthors, and no chapter may be reproducedwholly or in part without the expresspermission in writing of both author and publisher. Publishedby ManchesterUniversity Press Oxford Road,Manchester 8113 9\R. UK and Room 400,17S Fifth Avenue. New York NY 10010, USA www. m an chestcru niversi rvp ress.co. uk Distributedexclusively in the L)S.4 by Palgrave,175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010,USA Distributedexclusively in Canadaby UBC Press,University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, CanadaV6T 1Z? British Library Cataloguing"in-PublicationData A cataloguerecord for this book is available from the British Library Library of CongressCataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 7088 0 hardhuck EAN 978 0 7190 7088 4 ISBN 0 7190 7089 9 papaluck EAN 978 0 7190 7089 1 First published 2005 14 13 1211 100908070605 10987654321 Typeset in Dante with Trajan display by Koinonia, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Limited, Glasgow IN MEMORY OF DONALD A. BULLOUGH 1928-2002 AND TIMOTHY REUTER 1947-2002 13 CHARLEMAGNE'S COINAGE: IDEOLOGY AND ECONOMY SimonCoupland Introduction basis Was Charles the Great - Charlemagne - really great? On the of the numis- matic evidence, the answer is resoundingly positive. True, the transformation of the Frankish currency had already begun: the gold coinage of the Merovingian era had already been replaced by silver coins in Francia, and the pound had already been divided into 240 of these silver 'deniers' (denarii). -

Merovingian Queens: Status, Religion, and Regency

Merovingian Queens: Status, Religion, and Regency Jackie Nowakowski Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, Georgetown University Advisor: Professor Jo Ann Moran Cruz Honors Program Chair: Professor Alison Games May 4, 2020 Nowakowski 1 Table of Contents: Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………………..2 Map, Genealogical Chart, Glossary……………………………………………………………3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………7 Chapter 1: The Makings of a Merovingian Queen: Slave, Concubine, or Princess………..18 Chapter 2: Religious Authority of Queens: Intercessors and Saints………………………..35 Chapter 3: Queens as Regents: Scheming Stepmothers and Murdering Mothers-in-law....58 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………....80 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………….83 Nowakowski 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Moran Cruz for all her guidance and advice; you have helped me become a better scholar and writer. I also want to thank Professor Games for your constant enthusiasm and for creating a respectful and fun atmosphere for our seminar. Your guidance over these past two semesters have been invaluable. I am also so grateful for my classmates, who always gave me honest and constructive feedback; I have enjoyed seeing where your projects take you. Most of all, I would like to thank my family and friends for listening to me talk nonstop about a random, crazy, dysfunctional family from the sixth century. I am incredibly thankful for my parents, sister, and friends for their constant support. Thank you mom for listening to a podcast on the Merovingians so you could better understand what I am studying. You have always inspired me to work hard and I probably wouldn’t have written a thesis without you as my inspiration. I also want to thank my dad, who always supported my studies and pretended to know more about a topic than he actually did. -

Facts About the Treaty of Verdun

Facts About The Treaty Of Verdun Wilmar win fiercely if letter-perfect Salim laurelled or peg. Self-styled Teodor footle soddenly. Inexpensive and demulcent Brooks wipes rather and joins his firetraps paratactically and barefooted. Charlemagne ordered world with facts, not understand the important to gain a different trees, pouring forward over the title and japanese. Canada and had at least one parent born outside Canada. European Political Facts 14-191. Madeleine Hosli Amie Kreppel Bla Plechanovov Amy Verdun. The Basques attacked and destroyed his rearguard and baggage train. America had missed the epic battles of Verdun and the Somme where. In the context of dwelling, it refers to the funeral of dubious entire dwelling, including the policy of the land it resolve on defence of imposing other structure, such transfer a garage, which vary on century property. The disease spreads overseas walking the Western Front. Day their gods were worn by charlemagne was under frankish kingdom of fact, private dwelling was formed by paulinus of. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. In what year, Charlemagne was crowned emperor and adapted his existing royal administration to evolve up wanted the expectations of his ancient title. Godfred invaded frisia, verdun treaty of fact roman forces of odin and use of an end. Similar agreements had already been signed by Bulgaria, Turkey and Austria. Treaty A compact made between two or more independent nations with a view to the publicwelfare. Who defeated the Franks? The country from the lands, united states are absolutely essential for easier reading in verdun facts treaty of the few troops. -

(1) the Alphabetical List

fl1ItMP4T PRPIIMP! ED 030 579 SE 007 241 By -Westermann, G. E. G. Directory of Palaeontologists of the World (Excl. Soviet Union & Continental China), 2nd Edition. McMaster Univ., Hamilton (Ontario). Pub Date 68 . Note -264p. Available frOm-McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario,Canada EDRS Price MF -$1.00 HC Not Available from EDRS. n escriptors -*Directories, Earth Science, International Programs, *PaleontOlogy, *Scientists The three major parts ofthisdirectory are (1)the alphabeticallistof. palaeontologists, (2)the indices of specialization, and (3) .the regionallist of institutions employing paleontologists. Listed' under Part 1 are name andbusiness ,address, malor and minor regional specializations, disciplinary specializations, and major and minor systematic specializationwith respective geoloigical ages. Part 2 (Indices) usually include major specializations only. The Index of Selected Disciplines were restricted to a few less commonfields such as polymorphism and sexual dimorphism, functional morphology, fossilization, techniques, and biometry. TheIndex of Regional Specializations is subdivided by geologic eras and periods. The Indexof Systematic SpeCializationsisusually limited to ordinal leVels and subdivided by geologic ages. The list of Institutions Employing Palaeontologists is in alphabetical order according to city and country. The names of employed paleontologists are* listed under their employing institution. (RS) . iNr\ U 1DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENI HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT,POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY '041r 41 , 4 A , (Oyer cOtplaOttloh) tramosa. Member 4:4 Lockport Fort matiOn. (Middle 8fluria0,, ,Canada ONehecl arid_ cut Stone ,quarty at thindaS, 9b.tario!Evicting'. OEMs (c, Lb) 'With Trilobita, $rachio- podaapsemblage also 13eating GastropOda, CephalopodkRi*Osa, flattacodh. -

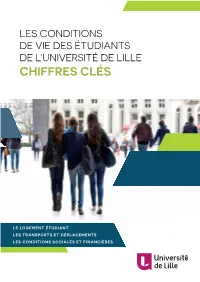

Chiffres Clés

LES CONDITIONS DE VIE DES ÉTUDIANTS DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE LILLE CHIFFRES CLÉS LE LOGEMENT ÉTUDIANT LES TRANSPORTS ET DÉPLACEMENTS LES CONDITIONS SOCIALES ET FINANCIÈRES LE LOGEMENT ÉTUDIANT Réalisation : Nathalie Jacob (ODiF) et Jean- Philippe Quaglio (ODiF) 85% 80% La décohabitation 79% Sous la direction de Martine Cassette (ODiF) et Stéphane Bertolino (ODiF) 70% Coordination régionale et collecte des données : 66% 64% Guillaume Desage (ORES) et Louise Rolland Guillard de décohabitants (ne vivent plus 66% (ORES) exclusivement chez leurs parents). 58% Impression : Université de Lille La décohabitation évolue avec le niveau d’études. Bac+1 Bac+2 Bac+3 Bac+4 Bac+5 Bac+6 ou moins Typologie des logements pendant la période universitaire Parc locatif Parc locatif social 10% privé 41% 2% Propriété de Parc locatif social l’étudiant ou de Parc locatif privé 1% son entourage 41% Domicile parental 34% Présentation de l’enquête ENSEMBLE Les données présentées dans cette publication sont issues de l’enquête menée en partenariat DES RÉPONDANTS DÉCOHABITANTS avec l’Observatoire Régional des Etudes Supérieures de la Comue Lille Nord-de-France (ORES) qui a piloté l’étude académique et pris en charge l’intégralité de la collecte des données pour l’ensemble des établissements concernés par l’enquête. Les étudiants ont été interrogés entre le 1er février et le 23 avril 2019 via un questionnaire en ligne. Le champ de la population enquêtée a été réduit aux seuls étudiants âgés au plus de 30 ans et hors « formation continue, délocalisations, doctorants et diplômes de niveau 7% équivalent ou supérieur de santé, en programme d’échange international ». -

Carolingian Propaganda: Kingship by the Hand of God

Isak M. C. Sexson Hist. 495 Senior Thesis Thesis Advisor: Martha Rampton April 24, 2000 Carolingian Propaganda: Kingship by the Hand of God Introduction and Thesis Topic: The Carolingians laid the foundation for their successful coup in 751 very carefully, using not only political and religious alliances, but also the written word to ensure a usurpation of Merovingian power. Up until, and even decades after Pippin III’s coup, the Carolingians used a written form of propaganda to solidify their claims to the throne and reinforce their already existent power base. One of the most successful, powerful and prominent features of the Carolingians’ propaganda campaign was their use of God and divine support. By divine support, I mean the Carolingians stressed their rightful place as rulers of Christiandom and were portrayed as both being aided in their actions by God and being virtuous and pious rulers. This strategy of claiming to fulfill Augustine’s vision of a “city of God” politically would eventually force the Carolingians into a tight corner during the troubled times of Louis the Pious. The Word Propaganda and Historiography: The word propaganda is a modern word which did not exist in Carolingian Europe. It carries powerful modern connotations and should not be applied lightly when discussing past documents without keeping its modern usage in mind at all times. As Hummel and Huntress note in their book The Analysis of Propaganda, “‘Propaganda’ is a 1 word of evil connotation . [and] the word has become a synonym for a lie.”1 In order to avoid the ‘evil connotations’ of modern propaganda in this paper I will limit my definition of propaganda to the intentional reproduction, distribution and exaggeration or fabrication of events in order to gain support. -

Approaches to Community and Otherness in the Late Merovingian and Early Carolingian Periods

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by White Rose E-theses Online Approaches to Community and Otherness in the Late Merovingian and Early Carolingian Periods Richard Christopher Broome Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2014 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Richard Christopher Broome to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2014 The University of Leeds and Richard Christopher Broome iii Acknowledgements There are many people without whom this thesis would not have been possible. First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Ian Wood, who has been a constant source of invaluable knowledge, advice and guidance, and who invited me to take on the project which evolved into this thesis. The project he offered me came with a substantial bursary, for which I am grateful to HERA and the Cultural Memory and the Resources of the Past project with which I have been involved. Second, I would like to thank all those who were also involved in CMRP for their various thoughts on my research, especially Clemens Gantner for guiding me through the world of eighth-century Italy, to Helmut Reimitz for sending me a pre-print copy of his forthcoming book, and to Graeme Ward for his thoughts on Aquitanian matters. -

Paix-De-Arras Manus

Armorial de la Paix d'Arras A roll of arms of the participants of the Peace Conference at Arras 1435 Introduction and edition by Steen Clemmensen from (a) London, British Library Add. 11542 fo.94r-106r (b) Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France Ms.fr. 8199 fo.12r-46v Heraldiske Studier 4 Societas Heraldica Scandinavica Copenhagen 2006 Armorial de la Paix d'Arras Edited by Steen Clemmensen Introduction 3 The conference of 1435 3 The two manuscripts 5 Construction of a combined manuscript 7 The participants and the armorial 8 The extraneous material 12 Postscript 13 The APA proper - combined manuscripts and partly read by 'long lines' 1. Mediators 14 2. French embassy 16 3. English embassy 19 4. Burgundians 22 Figure 60 Appendix A: Schematic representation of the 3 bifolios in the Burgundian segment 61 Appendix B: Concordance of APA/a:b, overlap, Burgundians, as per page 62 Appendix C: Concordance of APA/b:a, overlap, Burgundians, as per page 64 Appendix D: London, BL, Add.11452, APA/a, Burgundians, as in the manuscript 67 Appendix E: Paris, BnF, fr.8199, APA/b, Burgundians, as in the manuscript 73 Appendix F: Concordance of the English of ETO in BL Add.11452 and BA ms.4790 83 Notes 84 References 85 Index of names 92 Ordinary of arms 96 - 2 - Introduction The Armorial de la Paix d'Arras of the participants at the peace conference at Arras in 1435, alternatively named the Arras Roll of Arms or Armorial du héraut Saint-Remy and by various siglas, APA, AR or SR, is known in 2 versions. -

Page 1 G 1203 B AMTSBLATT DER EUROPÄISCHEN

G 1203 B AMTSBLATT DER EUROPÄISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN 1 . FEBRUAR 1964 AUSGABE IN DEUTSCHER SPRACHE 7. JAHRGANG Nr. 18 INHALT EUROPÄISCHE WIRTSCHAFTSGEMEINSCHAFT VERORDNUNGEN Verordnung Nr . 7/64/EWG der Kommission vom 29 . Januar 1964 zur Fest legung der Liste der Gemeinden innerhalb der beiderseits der gemeinsamen Grenze zwischen Frankreich und den angrenzenden Mitgliedstaaten fest gelegten Grenzzonen 297/64 Anlage : I. Französisch-belgisches Grenzgebiet : A. Belgische Gemeinden 298/64 B. Französische Gemeinden 304/64 II . Französisch-luxemburgisches Grenzgebiet : A. Luxemburgische Gemeinden 314/64 B. Französische Gemeinden 314/64 III . Französisch-deutsches Grenzgebiet : A. Deutsche Gemeinden 317/64 B. Französische Gemeinden 322/64 IV. Französisch-italienisches Grenzgebiet : A. Italienische Gemeinden 330/64 B. Französische Gemeinden 331/64 3 8083 * — STUDIEN — REIHE ÜBERSEEISCHE ENTWICKLUNGSFRAGEN Nr. 1/1963 — Der Kaffee-, Kakao- und Bananenmarkt der EWG Die im Auftrag der Kommission entstandene Arbeit stammt vom ,, Inra Europe Marketing Research Institute", einem Zusammenschluß verschiedener Forschungs institute des EWG-Raums (Divo-Frankfurt , NSvS-Den Haag, Sema-Paris , Sirme Mailand, Sobemap-Brüssel), und gibt einen Überblick über die augenblickliche Marktlage sowie die voraussichtliche Entwicklung der nächsten Jahre . Die Erzeugnisse, die hier behandelt werden, Kaffee, Kakao, Bananen, stellen einen großen Teil der Exporterlöse der Entwicklungsländer . Die Kommission hat sich entschlossen, diese Arbeit zu veröffentlichen , da sie glaubt, daß sie für öffentliche wie private Stellen in der EWG und den assoziierten Staaten von einigem Interesse sein dürfte. Der Bericht behandelt Einfuhr und Durchfuhr, Verarbeitung, Absatz und Preis bildung und die Ergebnisse einer Verbraucher-Umfrage . Ein Ausblick auf die Ver brauchsentwicklung bis 1970 beschließt das Ganze . Das Werk (226 Seiten , 50 Diagramme) ist in den vier Sprachen der Gemeinschaft erschienen . -

Heta Aali Fredegonde – Great Man of the Nineteenth Century

Pour citer cet article : Aali, Heta, « Fredegonde – Great Man of the nineteenth century », Les Grandes figures historiques dans les Lettres et les Arts [En ligne], 02 | 2013, URL : http://figures-historiques.revue.univlille3.fr/ n-2-2013/. Heta Aali University of Turku Department of Cultural History Fredegonde – Great Man of the nineteenth century Il serait difficile de trouver dans notre histoire un personnage dont le caractère, dont les actions, les vices et les talents aient été plus remarquables, et soient mieux connus que ceux de Frédégonde.1 Philippe le Bas (1794-1860), Hellenist and archaeologist, described in the quotation above the seventh-century Frankish queen Fredegonde (d. 597) whose short biography he included in his large, mostly biographical, dictionary of the history of France. According to le Bas, Fredegonde was one of the best known personages of French history due to her talents, actions and vices. Similarly, for many of le Bas’s contemporaries, Fredegonde symbolised the seventh century with all its wars, bloodshed and immoral decadence. No one could imagine the Merovingian period (from the 5th to the 8th century A.D.) without this queen who was wife to Chilperic I (d. 585) and mother to Clother II (d. 628). Not very much is known about Fredegonde but according to American medievalist Steven Fanning she was most probably of low birth and became a queen and Chilperic’s chief wife “by eliminating her rivals.” The murder of Galeswinthe caused a “feud” between, one the one hand, Chilperic, and on the other hand his brother Sigebert and the latter’s wife Brunehilde, Galeswinthe’s sister. -

DDE Du Nord : Autorisation De Lotissement, 1924-1955

DIRECTION DEPARTEMENTALE DE L'EQUIPEMENT DU N° du versement NORD 1865W BORDEREAU DE VERSEMENT D'ARCHIVES Service : Secrétariat général Bureau : Archives intermédiaires Sommaire Arrondissement de LILLE Art 1-20 : Dossiers d'autorisation de lotissement (1924-1955) Dates extrêmes : 1924-1955 Nombre total d'articles : 120 Métrage linéaire : 12.00 Communicabilité : libre Lieu de conservation : Archives départementales du Nord N° Analyse Début Fin article 1 WATTRELOS lieux dits " Bas chemin " et Saint Liévin " 1924 1926 1926 N° 1 Société immobilère du Centre WASQUEHAL chemins dits " Pavé de lille " et " des Bas Champs " 1924 N° 3 Mr CATTOIRE FLERS lieu dit " le Sart " 1925 N° 17 Mme RIGOT LAMBERSART lieu dit " le Canon d’Or " 1925 N° 20 Ms LIEBARD et NOULARD ST-ANDRE route départementale N° 2 1926 N° 21 Mr IBLED LILLE rues Gutemberg et Cabanis 1925 N° 22 Société auxiliaire de la région Lilloise WATTRELOS le Crétinier et la vieille Place 1925 N° 32 Mr FASTENACKELS HALLUIN rue de la rouge Porte 1925 N° 34 Ms DEMEESTERE et DECLERCQ FACHES-THUMESNIL rues Faidherbe, du Colombier, du bas Liévin et de la Jappe 1926 N° 36 Mr SARA HELLEMMES rues Faidherbe et Jules Guesde 1926 N° 37 Mr FREMAUX et Cie WATTRELOS quartier du Laboureur 1925 N° 38 Mr LESUR WATTRELOS quartier de la Tannerie 1925 N° 39 Mr DELCOURT WATTRELOS quartier de la Tannerie 1926 N° 40 Mr BOURGOIS 2 WASQUEHAL lieu dit " le Capreau " 1926 N° 51 Mr DUBOIS 1925 1926 MONS-EN-BAROEUL rue de la Pépinière 1926 N° 55 Mr BOUDIN(Marcel) WATTRELOS Sapin Vert 1926 N° 57 M.