The Role of Satirical News in Dissent, Deliberation, and Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TV Preview: Tales of Television Centre at BFI Southbank / Tue 15 May / 18:10

PRESS RELEASE April 2012 12/29 TV Preview: Tales of Television Centre At BFI Southbank / Tue 15 May / 18:10 BFI Southbank is delighted to present a preview screening of Tales of Television Centre, the upcoming feature-length documentary telling the story of one of Britain’s most iconic buildings as the BBC prepares to leave it. The screening will be introduced by the programme’s producer-director Richard Marson The story is told by both staff and stars, among them Sir David Frost, Sir David Attenborough, Dame Joan Bakewell, Jeremy Paxman, Sir Terry Wogan, Esther Rantzen, Angela Rippon, Biddy Baxter, Edward Barnes, Sarah Greene, Waris Hussein, Judith Hann, Maggie Philbin, John Craven, Zoe and Johnny Ball and much loved faces from Pan’s People (Babs, Dee Dee and Ruth) and Dr Who (Katy Manning, Louise Jameson and Janet Fielding). As well as a wealth of anecdotes and revelations, there is a rich variety of memorable, rarely seen (and in some cases newly recovered) archive material, including moments from studio recordings of classic programmes like Vanity Fair, Till Death Us Do Part, Top of the Pops and Dr Who, plus a host of vintage behind-the-scenes footage offering a compelling glimpse into this wonderful and eccentric studio complex – home to so many of the most celebrated programmes in British TV history. Press Contacts: BFI Southbank: Caroline Jones Tel: 020 7957 8986 or email: [email protected] Lucy Aronica Tel: 020 7957 4833 or email: [email protected] NOTES TO EDITORS TV Preview: Tales of Television Centre Introduced by producer-director Richard Marson BBC 2012. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’S Eve 2018 – the Night Is Yours

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’s Eve 2018 – The Night is Yours. Image: Jared Leibowtiz Cover: Dianne Appleby, Yawuru Cultural Leader, and her grandson Zeke 11 September 2019 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2019. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 11 September 2019 and provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC continues to be the home and source of Australian stories, told across the nation and to the world. The Corporation’s commitment to innovation in both storytelling and broadcast delivery is stronger than ever, as the needs of its audiences rapidly evolve in line with technological change. Australians expect an independent, accessible public broadcasting service which produces quality drama, comedy and specialist content, entertaining and educational children’s programming, stories of local lives and issues, and news and current affairs coverage that holds power to account and contributes to a healthy democratic process. The ABC is proud to provide such a service. The ABC is truly Yours. Sincerely, Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chair Letter to the Minister iii ABC Radio Melbourne Drive presenter Raf Epstein. -

Motion Film File Title Listing

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MOTION FILM FILE ● MFF-001 "On Guard for America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #1" (1950) One of a series of six: On Guard for America", TV Campaign spots. Features Richard M. Nixon speaking from his office" Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. Cross Reference: MVF 47 (two versions: 15 min and 30 min);. DVD reference copy available ● MFF-002 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #2" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. DVD reference copy available ● MFF-003 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #3" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office. Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. DVD reference copy available Monday, August 06, 2018 Page 1 of 202 Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MOTION FILM FILE ● MFF-004 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #4" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office. Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

Project Catalyst Magazine 2018

PROJECT CATALYST 2018 – THE EVOLUTION OF INNOVATION – HARVESTING IDEAS IN SUGAR TEN YEARS HARVESTING IDEAS FOSTERING INNOVATION CORAL & CANDY Catalyst growers inspiring The innovation challenge EMBRACING TECHNOLOGY next gen to 2030 Why farmers need data Image: Jeppersen Farm visit with Coca-Cola, WWF and Catalyst growers Mackay. TEN YEARS As we meet again for Project Catalyst Forum They say it takes a village to raise a child flow freely across mill and regional boundaries – 2018, we reflect on 10 years since a group of well I think it takes a community to deliver a this is part of the glue that holds our community forward thinking growers and representatives program like Project Catalyst. We are a diverse together. The other is that like-minded growers from Reef Catchments, WWF and Coca-Cola community of growers across multiple mill areas share a bond through the trials and forums that got together to form what is now a highly / growing regions, with partners from industry strengthens the community. Growers are able regarded and successful sugar cane innovation and government as well as service providers to talk to each other all year because of these program. and supporters. There is a commitment to connections. our community’s brand just like there is for a I never cease to be amazed at how Project sporting team and there will always be highs and 2017 was another year of media exposure for Catalyst has grown over the 10 years to cover lows, but by working together collaboratively we Project Catalyst highlighted by the September the three regions and involve more than 100 have grown and protected our community. -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

A Fighting Force for Mental Health

SANE: A fighting force for mental health Famous personalities who are friends and Vice Patrons of SANE are speaking up for those whose voices are so often not heard. We are delighted that they give their time and talent for greater public understanding. Jane Asher: “Where SANE is so invaluable is in not only providing someone to talk to who understands and can offer encouragement, but also in giving the kind of practical information that is needed.” Fellow Vice Patrons: The Rt Hon the Lord Kinnock Lynda Bellingham: Professor Colin Blakemore FRS Hon FRCP “SANE is vital to sanity in the way society Rowan Atkinson deals with mental health.” Cherie Booth QC Frank Bruno MBE Michael Buerk Stephanie Cole OBE Barry Cryer OBE Dame Judi Dench CH DBE Alastair Stewart OBE: Edward Fox OBE Sir David Frost OBE “Ignorance and prejudice are terrifying Barry Humphries AO CBE partners. SANE has always bravely and Virginia Ironside consistently battled against both and held high Sir Jeremy Isaacs the banners of care and compassion.” Gary Kemp Ross Kemp Nick Mason Ian McShane Carole Stone: Anna Massey CBE “As someone whose brother suffered from paranoid Sir Jonathan Miller CBE schizophrenia, I am very pleased to be a patron of David Mitchell SANE. I only wish it had been available to me and my James Naughtie family in those days.” Trevor Phillips Tim Pigott-Smith Griff Rhys Jones Barry Cryer: Nick Ross Timothy Spall OBE “The crazier the world gets, the more we need SANE. They are completely Juliet Stevenson CBE involved with the people they help. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Discourse Types in Stand-Up Comedy Performances: an Example of Nigerian Stand-Up Comedy

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2015.3.1.filani European Journal of Humour Research 3 (1) 41–60 www.europeanjournalofhumour.org Discourse types in stand-up comedy performances: an example of Nigerian stand-up comedy Ibukun Filani PhD student, Department of English, University of Ibadan [email protected] Abstract The primary focus of this paper is to apply Discourse Type theory to stand-up comedy. To achieve this, the study postulates two contexts in stand-up joking stories: context of the joke and context in the joke. The context of the joke, which is inflexible, embodies the collective beliefs of stand-up comedians and their audience, while the context in the joke, which is dynamic, is manifested by joking stories and it is made up of the joke utterance, participants in the joke and activity/situation in the joke. In any routine, the context of the joke interacts with the context in the joke and vice versa. For analytical purpose, the study derives data from the routines of male and female Nigerian stand-up comedians. The analysis reveals that stand-up comedians perform discourse types, which are specific communicative acts in the context of the joke, such as greeting/salutation, reporting and informing, which bifurcates into self- praising and self denigrating. Keywords: discourse types; stand-up comedy; contexts; jokes. 1. Introduction Humour and laughter have been described as cultural universal (Oring 2003). According to Schwarz (2010), humour represents a central aspect of everyday conversations and all humans participate in humorous speech and behaviour. This is why humour, together with its attendant effect- laughter, has been investigated in the field of linguistics and other disciplines such as philosophy, psychology, sociology and anthropology. -

For U.S. Tha Baptiat Church

9. ' i t. : #s' • ,/■ FRIDAY, AUGUST 26, 19M f'"' . -JL - y " V-4 iRanck^stcr lEvpnitis Irralb psJTvT...,^ You E s^ped Flood Dim8tei*"llelp Those Who DidnH-.-Give n j ^ Q w n Velvet Sales -«( tka MFD «i1w V r. ictMt* In tha Seen by Avelaio Dal^ Net Press Ron „ _ , tomocraw an J Fee Uw Weak BBSae I eC 0 . n . Wealb UHt -Um panda hat iMan AngBaC S i, IN S . jad dua to flood oondltioas. Cheney Bros. 'a tta n a ta data haa feaan .an* cotiD m Chaoay Broa. valvet production 11333 eael taBlgM.' rataivad hatlon-wida attention MeuBkae-el the A unt •tha Kaa. CItarlaa M. Btjrren Bb n b b a« OInrtBtlaa 'fNmtka rtn t Pariah, Uncoln. earlier thia month In an article Manehs$Ur~^A City of Viliogo Charm Uam.. wOl ba (uaat mialatar Sun blUhad in Women'a Wear wtth a Franch aooaiit... day at'»:U ajn. in Cantor Church. Silly, a trade newapaper for the texula and women'a apparel in- W t ana aradoatad (ram Ohio Wea- MANCHESTER, CONN^ SATURDAY, AUGUST 37, 1955 I t) PRICE nV B CENTS l«wan U n tro M ^ and Unlan Thao- duatrica^ X ▼OL. LXX1V.no . 279 (TWELVE PAGES) loclcal damhaary, Na«r Toik. and The article,. which appeared in RAIssion VaUay plafdsi ana aaaooiata minlatar f t Canter le Any. 8 isaue of the trade Churah,. Naw Britain, and Can tar s:per, aaid that Cheney Broa. an* Ghunh.. Hartford, bafon aaaumlnf ticipatea an rincreaae in the pro tha paatorata n t Uncoln. -

Blunderful-World-Of-Bloopers.Pdf

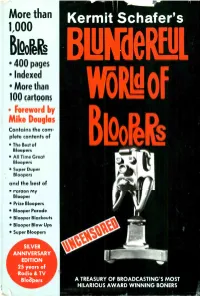

o More than Kermit Schafer's 1,000 BEQ01416. BLlfdel 400 pages Indexed More than 100 cartoons WÖLof Foreword by Mike Douglas Contains the com- plete contents of The Best of Boo Ittli Bloopers All Time Great Bloopers Super Duper Bloopers and the best of Pardon My Blooper Prize Bloopers Blooper Parade Blooper Blackouts Blooper Blow Ups Super Bloopers SILVER ANNIVERSARY EDITION 25 years of Radio & TV Bloópers A TREASURY OF BROADCASTING'S MOST HILARIOUS AWARD WINNING BONERS Kermit Schafer, the international authority on lip -slip- pers, is a veteran New York radio, TV, film and recording Producer Kermit producer. Several Schafer presents his Blooper record al- Bloopy Award, the sym- bums and books bol of human error in have been best- broadcasting. sellers. His other Blooper projects include "Blooperama," a night club and lecture show featuring audio and video tape and film; TV specials; a full - length "Pardon My Blooper" movie and "The Blooper Game" a TV quiz program. His forthcoming autobiography is entitled "I Never Make Misteaks." Another Schafer project is the establish- ment of a Blooper Hall of Fame. In between his many trips to England, where he has in- troduced his Blooper works, he lectures on college campuses. Also formed is the Blooper Snooper Club, where members who submit Bloopers be- come eligible for prizes. Fans who wish club information or would like to submit material can write to: Kermit Schafer Blooper Enterprises Inc. Box 43 -1925 South Miami, Florida 33143 (Left) Producer Kermit on My Blooper" movie opening. (Right) The million -seller gold Blooper record. -

Accelerated Reader Book List 08-09

Accelerated Reader Book List 08-09 Test Number Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 35821EN 100th Day Worries Margery Cuyler 3.0 0.5 107287EN 15 Minutes Steve Young 4.0 4.0 8251EN 18-Wheelers Linda Lee Maifair 5.2 1.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4.0 7351EN 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Jon Buller 2.5 0.5 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Gr Verne/Vogel 5.2 3.0 6201EN 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen 4.0 1.0 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4.0 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups A.K. Donahue 4.2 1.0 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubb Dr. Seuss 4.0 1.0 31170EN The 6th Grade Nickname Game Gordon Korman 4.3 3.0 413EN The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson 4.7 2.0 71428EN 95 Pounds of Hope Gavalda/Rosner 4.3 2.0 81642EN Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6.0 11151EN Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner 2.6 0.5 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3.0 76357EN The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6.0 9751EN Abiyoyo Pete Seeger 2.2 0.5 86635EN The Abominable Snowman Doesn't R Debbie Dadey 4.0 1.0 117747EN Abracadabra! Magic with Mouse an Wong Herbert Yee 2.6 0.5 815EN Abraham Lincoln Augusta Stevenson 3.5 3.0 17651EN The Absent Author Ron Roy 3.4 1.0 10151EN Acorn to Oak Tree Oliver S. Owen 2.9 0.5 102EN Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt 6.6 10.0 7201EN Across the Stream Mirra Ginsburg 1.7 0.5 17602EN Across the Wide and Lonesome Pra Kristiana Gregory 5.5 4.0 76892EN Actual Size Steve Jenkins 2.8 0.5 86533EN Adam Canfield of the Slash Michael Winerip 5.4 9.0 118142EN Adam Canfield,