Truth Commissions—Timor-Leste

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Governing the Ungovernable: Contesting and Reworking REDD+ in Indonesia

Governing the ungovernable: contesting and reworking REDD+ in Indonesia Abidah B. Setyowati1 Australian National University, Australia Abstract Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation plus the role of conservation, sustainable forest management, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries (REDD+) has rapidly become a dominant approach in mitigating climate change. Building on the Foucauldian governmentality literature and drawing on a case study of Ulu Masen Project in Aceh, Indonesia, this article examines the practices of subject making through which REDD+ seeks to enroll local actors, a research area that remains relatively underexplored. It interrogates the ways in which local actors react, resist or maneuver within these efforts, as they negotiate multiple subject positions. Interviews and focus group discussions combined with an analysis of documents show that the subject making processes proceed at a complex conjuncture constituted and shaped by political, economic and ecological conditions within the context of Aceh. The findings also suggest that the agency of communities in engaging, negotiating and even contesting the REDD+ initiative is closely linked to the history of their prior engagement in conservation and development initiatives. Communities are empowered by their participation in REDD+, although not always in the ways expected by project implementers and conservation and development actors. Furthermore, communities' political agency cannot be understood by simply examining their resistance toward the initiative; these communities have also been skillful in playing multiple roles and negotiating different subjectivities depending on the situations they encounter. Keywords: REDD+, subject-making, agency, resistance, Indonesia, Aceh Résumé La réduction des émissions dues à la déforestation et à la dégradation des forêts (REDD +) est rapidement devenue une approche dominante pour atténuer le changement climatique. -

The Solomon Islands “Ethnic Tension” Conflict and the Solomon Islands Truth and Reconciliation Commission: a Personal Reflection

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2018-01 Flowers in the Wall: Truth and Reconciliation in Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Melanesia Webster, David University of Calgary Press http://hdl.handle.net/1880/106249 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca FLOWERS IN THE WALL Truth and Reconciliation in Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Melanesia by David Webster ISBN 978-1-55238-955-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Partnership in the Gospel

Partnership in the Gospel A Report based on the Vision of the Archbishop of Melanesia On Sunday 17 April 2016 more than 4000 people gathered at St Barnabas Cathedral Honiara in the Solomon Islands to witness the enthronement of Archbishop George Takeli as the sixth Archbishop of Anglican Church of Melanesia. It was at this enthronement that he set out his vision for the future of the church of Melanesia. In the last 18 months he has been working to establish many of those ideas. I want in this report to reflect upon the key messages of that vision which Archbishop George Takeli has set out and the Church of Melanesia has begun trying to live out and implement. “God is always present with us.” Melanesian culture is pervaded by the realisation of the presence of God in all things. It is a culture immediately dependent on the land and sea to sustain the life of its people. When storms and cyclone come, as we have seen they often do, we have constantly seen how vulnerable these low-lying islands are, made still more vulnerable by climate change. We also see the resilience and courage of the people both in Solomon Islands and Vanuatu as they rebuild their lives after floods and cyclones and when forced to move whole villages and abandon islands due to rising sea levels. In our partnership with the Church of Melanesia we have much to learn from this closeness to creation- for we abandon our own stewardship of creation at our peril. But we also have much to learn about the presence of God in our daily lives- the gifts of God revealed in the food we eat, the water we drink, our homes providing shelter from the elements, the air we breathe and the many gifts of God we take for granted. -

March 9, 2014 the LIVING CHURCH CATHOLIC EVANGELICAL ECUMENICAL

Cambodia’s Killing Fields Holiness for Women Biblical Studies March 9, 2014 THE LIVING CHURCH CATHOLIC EVANGELICAL ECUMENICAL O God, who from the family of your servant David raised up Joseph to be the guardian of your incarnate Son and the spouse of his virgin mother: Give us grace to imitate his uprightness of life and his obedience to your commands; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. Collect for the Feast of Saint Joseph Lent Book Issue $5.50 livingchurch.org Westminster Communities of Florida H ONORABLE SERVICE GRANTResidents at Westminster Communities of Florida quickly find they enjoy life more fully now that they’re free from the time and expense of their home maintenance. They choose from a wide array of options in home styles, activities, dining, progressive fitness and wellness programs. Many of our communities also provide a range of health care services, if ever needed. For many residents, the only question left is: Why did I wait so long? Call us today to see why a move to a Westminster community is the best move you can make! Westminster Communities of Florida proudly offers financial incentives to retired Episcopal priests, Christian educators, missionaries, spouses and surviving spouses. Call Suzanne Ujcic today to see if you meet eligibility requirements. 800-948-1881ext. 226 Westminster Communities of Florida WestminsterRetirement.com THE LIVING CHURCH THIS ISSUE March 9, 2014 ON THE COVER | “It is past time for Joseph to receive NEWS appropriate attention beyond the 4 Joyous Reunion at General rather vapid devotional literature that so often surrounds him” FEATURES (see p. -

The Church of Melanesia 1849-1999

ISSN 1174-0310 THE CHURCH OF MELANESIA 1849 – 1999 1999 SELWYN LECTURES Marking the 150th Anniversary of the Founding of The Melanesian Mission EDITED BY ALLAN K. DAVIDSON THE COLLEGE OF ST JOHN THE EVANGELIST Auckland, New Zealand ISSN 1174-0310 THE CHURCH OF MELANESIA 1849 – 1999 1999 SELWYN LECTURES Marking the 150th Anniversary of the Founding of The Melanesian Mission EDITED BY ALLAN K. DAVIDSON THE COLLEGE OF ST JOHN THE EVANGELIST Auckland, New Zealand 2000 © belongs to the named authors of the chapters in this book. Material should not be reproduced without their permission. ISBN 0-9583619-2-4 Published by The College of St John the Evangelist Private Bag 28907 Remuera Auckland 1136 New Zealand TABLE OF CONTENTS Contributors 4 Foreword 5 1. An ‘Interesting Experiment’ – The Founding of the Melanesian Mission 9 Rev. Dr Allan K. Davidson 2. ‘Valuable Helpers’: Women and the Melanesian Mission in the Nineteenth Century 27 Rev. Dr Janet Crawford 3. Ministry in Melanesia – Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow 45 The Most Rev. Ellison Pogo 4. Missionaries and their Gospel – Melanesians and their Response 62 Rev. Canon Hugh Blessing Boe 5. Maori and the Melanesian Mission: Two ‘Sees’ or Oceans Apart 77 Ms Jenny Plane Te Paa CONTRIBUTORS The Reverend Canon Hugh Blessing Boe comes from Vanuatu. He was principal of the Church of Melanesia’s theological college, Bishop Patteson Theological College, at Kohimarama, Guadalcanal 1986 to 1995. He undertook postgraduate study at the University of Oxford and has a master’s degree from the University of Birmingham. He is currently enrolled as a Ph.D. -

VOLUNTEER TRAINING of TRAINER's MANUAL (Tots)

5th - 16th February, Guwahati & Shillong VOLUNTEER TRAINING OF TRAINER’S MANUAL (ToTs) 1 2 Contents VOLUNTEER TRAINING OF TRAINER’S MANUAL (ToTs) 1 GUWAHATI & SHILLONG 1 VOLUNTEER FUNCTIONAL AREA 2 5TH TO 16TH OF FEBURARY , 2016 2 1. SOUTH ASIAN GAMES 5 History 5 Culture Value 5 Peace, Perseverance & Progress 5 Member Countries 5 Bi annual event 5 2. NORTH EAST INDIA 6 Culture & Tradition of north India 6 Legacy 7 Organising Committee 12th South Asian Games 2106 3. VISION AND MISSION 8 Vision 8 Mission 8 4. EVENTS AND VENUES 8 Guwahati 8 Shillong 9 Functional Areas 9 5. VOLUNTEERS 17 Concept of volunteering 17 Benefits of becoming a volunteer 17 The volunteer Honour code 18 DO’S 18 DONT’S 19 6. ACCREDITATION 19 What is accreditation? 19 People requiring accreditation 19 3 Importance of accreditation 19 The accreditation card 20 Venues and zones 20 Access Privileges 20 Non Transferability of the accreditation card 20 7. WORKFORCE POLICIES 20 Appropriate Roles for Volunteers and its Policy : 20 1.Volunteers being absent from work : 20 2.Entry & Check in Policy for Volunteers: 20 3.Exit Checkout Policy for Volunteers: 21 4.Sub specific policies 21 8. DISCIPLINE OF VOLUNTEERS 21 Volunteer Grievance Redressal 22 9. BEHAVIOUR OF VOLUNTEERS 22 Respect for Others 22 Ensure a Positive Experience 23 Act professionally and take responsibility for actions 23 10. LEADERSHIP 23 Roles of Volunteers 23 A volunteer leader is a volunteer who: 23 Orienting and Training Volunteers 23 11. ENERGY ENTHUSIASM 24 12. PROBLEM SOLVING 24 OVERCOMING OBSTACLES 24 13. COMMUNICATION 25 Listening 25 Listen Actively 25 SPEAKING 25 14. -

Belait District

BELAIT DISTRICT His Majesty Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah ibni Al-Marhum Sultan Haji Omar ‘Ali Saifuddien Sa’adul Khairi Waddien Sultan and Yang Di-Pertuan of Brunei Darussalam ..................................................................................... Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Paduka Seri Baginda Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah ibni Al-Marhum Sultan Haji Omar ‘Ali Saifuddien Sa’adul Khairi Waddien Sultan dan Yang Di-Pertuan Negara Brunei Darussalam BELAIT DISTRICT Published by English News Division Information Department Prime Minister’s Office Brunei Darussalam BB3510 The contents, generally, are based on information available in Brunei Darussalam Newsletter and Brunei Today First Edition 1988 Second Edition 2011 Editoriol Advisory Board/Sidang Redaksi Dr. Haji Muhammad Hadi bin Muhammad Melayong (hadi.melayong@ information.gov.bn) Hajah Noorashidah binti Haji Aliomar ([email protected]) Editor/Penyunting Sastra Sarini Haji Julaini ([email protected]) Sub Editor/Penolong Penyunting Hajah Noorhijrah Haji Idris (noorhijrah.idris @information.gov.bn) Text & Translation/Teks & Terjemahan Hajah Apsah Haji Sahdan ([email protected]) Layout/Reka Letak Hajah Apsah Haji Sahdan Proof reader/Penyemak Hajah Norpisah Md. Salleh ([email protected]) Map of Brunei/Peta Brunei Haji Roslan bin Haji Md. Daud ([email protected]) Photos/Foto Photography & Audio Visual Division of Information Department / Bahagian Fotografi -

Message From·The Archbishop of Melanesia to The

MESSAGE FROM · THE ARCHBISHOP OF MELANESIA TO THE PROVINCE To all God's People in Melanesia : - We as the Independent Church of Melanesia have a great responsibility ahead of us. We all have a duty to do for God's Church and the Country. Soon our Country will become independent and everybody is expected to contri bute something. What is our contribution t o the Country? 1. The C.O.M. has inherited a goodly tradition from the past, both the Anglican tradition and our own Melanesian tradition. We must combine the two in order to give strength and meaning to our worship. 2. We must thank our Founders, Bishops Selwyn and Patteson and the great men and women of tbe past, especially our first Archbishop for planning and preparing our Church to be:.ome a Province. Each one of us must be willing to work hard, work together and believe in God for what He wants His Church to be in the future. J. The many changes that have come to our Islands have caused confusion and doubts in the minds of some of our people. They ar~ involved in many different kinds of work and activities which are very good, but as a re sult these involvements weaken the work of the Church in some parts. What we need today, more than ever is the awakening or developing of the spiritual life of our People, and the training of our people to have a right attitude to life and work~ Also to have a better understanding and relationship with each othero 4. -

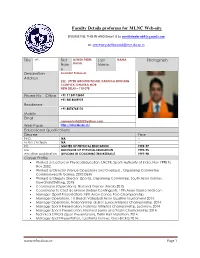

View Profile

Faculty Details proforma for MLNC Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] cc: [email protected] Title MR. First ASHISH PREM Last NAMA Photograph Nam SINGH Name e Designation Assistant Professor Address 222- UPPER GROUND FLOOR, KAKROLA HOUSING COMPLEX, DWARKA MOR NEW DELHI – 110 078 Phone No Office +91 11 24112604 +91 9818049974 Residence +91 8076768110 Mobile Email [email protected] Web-Page http://mlncdu.ac.in/ Educational Qualifications Degree Year Ph.D. NA -- M.Phil. / M.Tech. NA -- PG MASTER OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION 1995-97 UG BACHELOR OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION 1992-95 Any other qualification DIPLOMA IN COACHING [BASKETBALL] 1997-98 Career Profile Worked as Lecture in Physical Education, LNCPE, Sports Authority of India, Nov 1998 to Nov 2002. Worked as Director (Venue Operations and Overlays) , Organising Committee Commonwealth Games, 2010 Delhi Worked as Deputy Director (Sports), Organising Committee, South Asian Games, Guwahati/Shillong, 2015. Coordinator (Operations), National Games, Kerala 2015. Coordinator to Chef de Mission (Indian Contingent), 17th Asian Games Incheon. Manager (Sport Presentation) 15th Asian Canoe Polo Championship. Manager Operations, 1st Beach Volleyball Asian Qualifier tournament 2014. Manager Operations, National Inter-district Junior Athletics Championship, 2014. Manager Sports Presentation, National Athletics Championship, Lucknow, 2014. Manager Sports Presentation, National Junior and Youth Championship 2014. Technical Official (Sport Presentation), Delhi Half Marathon, 2014. Manager Sport Presentation, Lusofonia Games, Goa (India) 2014. www.mlncdu.ac.in Page 1 Administrative Assignments THE INTERNATIONAL SESSION FOR EDUCATORS AND OFFICIALS OF HIGHER INSTITUTES OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION, International Olympic Academy, Athens (GREECE) June 2011. Sports Administration of the Olympic Solidarity, Sports Administration Programme2004. -

Kamu Terim Bankası

TÜRKÇE-İNGİLİZCE Kamu Terim Ban•ka•sı Kamu kurumlarının istifadesine yönelik Türkçe-İngilizce Terim Bankası Term Bank for Public Institutions in Turkey Term Bank for use by public institutions in Turkish and English ktb.iletisim.gov.tr Kamu Terim Ban•ka•sı Kamu kurumlarının istifadesine yönelik Türkçe-İngilizce Terim Bankası Term Bank for Public Institutions in Turkey Term Bank for use by public institutions in Turkish and English © İLETİŞİM BAŞKANLIĞI • 2021 ISBN: 978-625-7779-95-1 Kamu Terim Bankası © 2021 CUMHURBAŞKANLIĞI İLETİŞİM BAŞKANLIĞI YAYINLARI Yayıncı Sertifika No: 45482 1. Baskı, İstanbul, 2021 İletişim Kızılırmak Mahallesi Mevlana Bulv. No:144 Çukurambar Ankara/TÜRKİYE T +90 312 590 20 00 | [email protected] Baskı Prestij Grafik Rek. ve Mat. San. ve Tic. Ltd. Şti. T 0 212 489 40 63, İstanbul Matbaa Sertifika No: 45590 Takdim Türkiye’nin uluslararası sahada etkili ve nitelikli temsili, 2023 hedeflerine kararlılıkla yürüyen ülkemiz için hayati öneme sahiptir. Türkiye, Sayın Cumhurbaşkanımız Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’ın liderliğinde ortaya koyduğu insani, ahlaki, vicdani tutum ve politikalar ile her daim barıştan yana olduğunu tüm dünyaya göstermiştir. Bölgesinde istikrar ve barışın sürekliliğinin sağlanması için büyük çaba sarf eden Türkiye’nin haklı davasının kamuoylarına doğru ve tutarlı bir şekilde anlatılması gerekmektedir. Bu çerçevede kamu kurumları başta olmak üzere tüm sektörlerde çeviri söylem birliğini sağlamak ve ifadelerin yerinde kullanılmasını temin etmek büyük önem arz etmektedir. İletişim Başkanlığı, Devletimizin tüm kurumlarını kapsayacak ortak bir dil anlayışını merkeze alan, ulusal ve uluslararası düzeyde bütünlüklü bir iletişim stratejisi oluşturmayı kendisine misyon edinmiştir. Bu doğrultuda Başkanlığımız kamu sektöründe yürütülen çeviri faaliyetlerinde ortak bir dil oluşturmak, söylem birliğini sağlamak ve çeviri süreçlerini hızlandırmak amacıyla çeşitli çalışmalar yapmaktadır. -

40 Years After Roe: Saving Lives

ADVANCES IN VIETNAM-HOLY SEE RELATIONS | PAGE 5 Pro-life pregnancy centers find right formula to give expectant mothers a sense of security and support both before and after their children are born. In the process, they are lowering the abortion rates in their communities. >NEWS ANALYSIS, PAGES 6-8 JANUARY 20, 2013 40 YEARS AFTER ROE: SAVING LIVES MORE PRO-LIFE STORIES Four decades after landmark ruling, pro-life activists of all generations work to promote sanctity of all human life. >SPECIAL SECTION, PAGES 9-16 Pro-lifers face challenge of changing Author-activist Monica Migliorino hearts of Americans who oppose abortion, Miller discusses book about her but favor keeping it legal. radical response to abortion. >NEWS ANALYSIS, PAGE 4 >FAITH, PAGES 18-19 VOLUME 101, NO. 38 • $3.00 WWW.OSV.COM ABOVE: WOMEN’S CARE CENTER FOUNDATION; LEFT: CNS 2 JANUARY 20, 2013 IN THIS ISSUE OUR SUNDAY VISITOR OPENERS | MARYANN GOGNIAT EIDEMILLER Dismissing ‘the big lie’ that abortion provides a better life uring my interview with tend you were never the mother The father of the baby never son together. and too old now. Dr. Day Gardner for the of a child.” had a chance to make it right, That marriage ended in di- But again, she chose life. articlesD in this week’s Respect Many of us know of someone though he wanted to, because vorce and annulment decades That unplanned baby is Life special section (Pages who has had an abortion, and my friend’s controlling mother later, and the woman was en- nearly 23 years old and is a trea- 9-16), she talked about “the big we all know someone who was forced her to “go away” and joying great freedom. -

Goa University Glimpses of the 22Nd Annual Convocation 24-11-2009

XXVTH ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 asaicT ioo%-io%o GOA UNIVERSITY GLIMPSES OF THE 22ND ANNUAL CONVOCATION 24-11-2009 Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon ble President of India, arrives at Hon'ble President of India, with Dr. S. S. Sidhu, Governor of Goa the Convocation venue. & Chancellor, Goa University, Shri D. V. Kamat, Chief Minister of Goa, and members of the Executive Council of Goa University. Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon'ble President of India, A section of the audience. addresses the Convocation. GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 XXV ANNUAL REPORT June 2009- May 2010 GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU GOA 403 206 GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 GOA UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR H. E. Dr. S. S. Sidhu VICE-CHANCELLOR Prof. Dileep N. Deobagkar REGISTRAR Dr. M. M. Sangodkar GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 CONTENTS Pg, No. Pg. No. PREFACE 4 PART 3; ACHIEVEMENTS OF UNIVERSITY FACULTY INTRODUCTION 5 A: Seminars Organised 58 PART 1: UNIVERSITY AUTHORITIES AND BODIES B: Papers Presented 61 1.1 Members of Executive Council 6 C; ' Research Publications 72 D: Articles in Books 78 1.2 Members of University Court 6 E: Book Reviews 80 1.3 Members of Academic Council 8 F: Books/Monographs Published 80 1.4 Members of Planning Board 9 G. Sponsored Consultancy 81 1.5 Members of Finance Committee 9 Ph.D. Awardees 82 1.6 Deans of Faculties 10 List of the Rankers (PG) 84 1.7 Officers of the University 10 PART 4: GENERAL ADMINISTRATION 1.8 Other Bodies/Associations and their 11 Composition General Information 85 Computerisation of University Functions 85 Part 2: UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS/ Conduct of Examinations 85 CENTRES / PROGRAMMES Library 85 2.1 Faculty of Languages & Literature 13 Sports 87 2.2 Faculty of Social Sciences 24 Directorate of Students’ Welfare & 88 2.3 Faculty of Natural Sciences 31 Cultural Affairs 2.4 Faculty of Life Sciences & Environment 39 U.G.C.