U N D E R S T a N D I N G Your Lab Re S U L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Your A1C Test

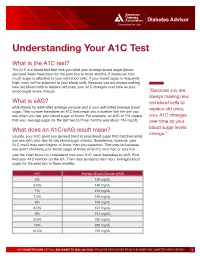

Diabetes Advisor Understanding Your A1C Test What is the A1C test? The A1C is a blood test that tells you what your average blood sugar (blood glucose) levels have been for the past two to three months. It measures how much sugar is attached to your red blood cells. If your blood sugar is frequently high, more will be attached to your blood cells. Because you are always making new red blood cells to replace old ones, your A1C changes over time as your blood sugar levels change. “Because you are always making new What is eAG? red blood cells to eAG stands for estimated average glucose and is your estimated average blood replace old ones, sugar. This number translates an A1C test result into a number like the one you see when you test your blood sugar at home. For example, an A1C of 7% means your A1C changes that your average sugar for the last two to three months was about 154 mg/dL. over time as your What does an A1C/eAG result mean? blood sugar levels change.” Usually, your A1C gives you general trend in your blood sugar that matches what you see with your day-to-day blood sugar checks. Sometimes, however, your A1C result may seem higher or lower than you expected. That may be because you aren’t checking your blood sugar at times when it’s very high or very low. Use the chart below to understand how your A1C result translates to eAG. First find your A1C number on the left. -

Serological (Antibody) Testing for Covid-19

SEROLOGICAL (ANTIBODY) TESTING FOR COVID-19 Serological tests detect antibodies in the blood People in the early stages of COVID-19 might generated as part of the immune response test antibody negative despite being highly to a specific infection, such as infection with infectious. Additionally, some tests might give a SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. false positive result because of past or present Antibody tests are different from tests such as infection with other types of coronaviruses. polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and antigen False positive results are also more likely tests which detect the SARS-CoV-2 virus. when the percentage of the population with Many new serological tests for COVID-19 have the disease is low. The Idaho Division of Public been developed and have an emergency use Health discourages persons who have a positive authorization (EUA) from the U.S. Food and serology test from relaxing the precautions such Drug Administration (FDA). Only antibody tests as social distancing that are recommended for that have an FDA EUA should be used. The all Idahoans to prevent spread of coronavirus, Idaho Division of Public Health discourages and strongly discourages employers form the use of unauthorized serology-based assays relaxing the employee protections for an for diagnosis of COVID-19 or determining if employee solely based upon a positive serology someone is currently infected or had a prior test. infection. The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 (the Serological tests are not recommended for virus that causes COVID-19) infection is not COVID-19 diagnosis in most situations because well understood. -

Jaundice Protocol

fighting childhood liver disease Jaundice Protocol Early identification and referral of liver disease in infants fighting childhood liver disease 36 Great Charles Street Birmingham B3 3JY Telephone: 0121 212 3839 yellowalert.org childliverdisease.org [email protected] Registered charity number 1067331 (England & Wales); SC044387 (Scotland) The following organisations endorse the Yellow Alert Campaign and are listed in alphabetical order. 23957 CLDF Jaundice Protocol.indd 1 03/08/2015 18:25:24 23957 3 August 2015 6:25 PM Proof 1 1 INTRODUCTION This protocol forms part of Children’s Liver Disease Foundation’s (CLDF) Yellow Alert Campaign and is written to provide general guidelines on the early identification of liver disease in infants and their referral, where appropriate. Materials available in CLDF’s Yellow Alert Campaign CLDF provides the following materials as part of this campaign: • Yellow Alert Jaundice Protocol for community healthcare professionals • Yellow Alert stool colour book mark for quick and easy reference • Parents’ leaflet entitled “Jaundice in the new born baby”. CLDF can provide multiple copies to accompany an antenatal programme or for display in clinics • Yellow Alert poster highlighting the Yellow Alert message and also showing the stool chart 2 GENERAL AWARENESS AND TRAINING The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has published a clinical guideline on neonatal jaundice which provides guidance on the recognition, assessment and treatment of neonatal jaundice in babies from birth to 28 days. Neonatal Jaundice Clinical Guideline guidance.nice.org.uk cg98 For more information go to nice.org.uk/cg98 • Jaundice Community healthcare professionals should be aware that there are many causes for jaundice in infants and know how to tell them apart: • Physiological jaundice • Breast milk jaundice • Jaundice caused by liver disease • Jaundice from other causes, e.g. -

Apheresis Donation This Quick Reference Guide Will Help You Identify the Best Donation for Your Unique Blood Type

Apheresis Donation This quick reference guide will help you identify the best donation for your unique blood type. Donors now have the opportunity to make an apheresis (ay-fur-ee-sis) donation and donate just platelets, red cells, or plasma at blood drives. These individual components are vital for local patients in need. Platelets Control Bleeding Red Cells Deliver Oxygen Plasma transports blood cells & controls bleeding Donation Type Blood Types Requirements Donation Time A+, B+, O+ Over 75% of population has one of these blood types. Platelet Donation: Be healthy, weigh at least 114 lbs 2 hours cancer & surgery patients no aspirin for 48 hours Platelets only last five days after donation so the need is constant. O-, O+, A-, B- Special height, weight, Double Red: O-Negative is the 1 hour and hematocrit requirements. surgery, trauma patients, universal red cell donor. +25 min Please call us or see a staff member accident, & burn victims Only 17% of population has one of these negative blood types Plasma: AB+, AB- Trauma patients, burn Universal Plasma Donors 1 hour Be healthy, weigh at least 114 lbs victims, & patients with +30 min serious illness or injuries Only 4% of population How Apheresis works: Blood is drawn from the donor’s arm and the components are separated. Only the components being donated are collected while the remaining components are safely returned to the donor How to Schedule an Appointment: Please call 800-398-7888 or visit schedule.bloodworksnw.org. Walk-ins are also welcome at some blood drives, so be sure to ask our staff when you stop in. -

Lactose Tolerance Blood Test

Lactose tolerance blood test Lactose tolerance tests measure the ability of your intestines to break down lactose, a type of sugar found in milk and other dairy products. How the test is performed The lactose tolerance blood test looks for glucose in your blood. Your body creates glucose when lactose breaks down. For this test, several blood samples will be taken before and after you drink the lactose solution described above. For information on how a blood sample is obtained, see venipuncture. How to prepare for the test You should not eat for 8 hours before the test. Avoid strenuous exercise for 8 hours before the test. How the test will feel There should not be any pain or discomfort when giving a breath sample. When the needle is inserted to draw blood, some people feel moderate pain, while others feel only a prick or stinging sensation. Afterward, there may be some throbbing. Why the test is performed Your doctor may order these tests if you have signs of lactose intolerance. Normal Values The breath test is considered normal if the increase in hydrogen is less than 12 parts per million over your fasting (pre-test) level. The blood test is considered normal if your glucose level rises more than 30 mg/dL within 2 hours of drinking the lactose solution. A rise of 20-30 mg/dL is inconclusive. Note: Normal value ranges may vary slightly among different laboratories. Talk to your doctor about the meaning of your specific test results. The examples above show the common measurements for results for these tests. -

Patient Information Leaflet – Plasma Exchange Procedure

Therapeutic Apheresis Services Patient Information Leaflet – Plasma Exchange Procedure Introduction Antibodies, which normally help to protect you from infection, can begin to attack your own This leaflet has been written to give patients healthy cells, or an over production of proteins can information about plasma exchange (sometimes cause your blood to become thicker and slow down called plasmapheresis). If you would like any more the blood flow throughout your body. A plasma information or have any questions, please ask the exchange can help improve your symptoms, doctors and nurses involved in your treatment at although this may not happen immediately. the NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) Therapeutic Apheresis Services Unit. Although plasma exchange may help with symptoms, it will not normally cure your condition When you have considered the information given as it does not switch off the production of the in this leaflet, and after we have discussed the harmful antibodies or proteins. It is likely that procedure and its possible risks with you, we will this procedure will form only one part of your ask you to sign a consent form to indicate that you treatment. are happy for the procedure to go ahead. Before any further procedures we will again check that you are happy to proceed. How do we perform Plasma Exchange? What is a plasma exchange? Plasma exchange is performed using a machine Blood is made up of red cells, white cells and called a Blood Cell Separator which can separate platelets which are carried around in fluid called blood into its various parts. The machine separates plasma. -

Rotational Thromboelastometry Predicts Care Level in Covid-19

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.11.20128710; this version posted June 12, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Rotational Thromboelastometry predicts care level in Covid-19 1 2 3 4 Lou M. Almskog, MD ; Agneta Wikman, MD, PhD ; Jonas Svensson, MD ; 1 5 6 2 Michael Wanecek, MD, PhD ; Matteo Bottai, PhD ; Jan van der Linden, MD, PhD 7 8 9 ; Anna Ågren, MD, PhD . 1 Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, Capio St Göran’s Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden 2 Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden 3 Department of Clinical Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital and Department of CLINTEC, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden 4 Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden 5 Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden 6 Unit of Biostatistics, Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden 7 Perioperative Medicine and Intensive Care, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden 8 Coagulation Unit, Division of Hematology, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden 9 Department of Clinical Sciences, Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.11.20128710; this version posted June 12, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

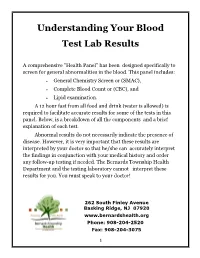

Understanding Your Blood Test Lab Results

Understanding Your Blood Test Lab Results A comprehensive "Health Panel" has been designed specifically to screen for general abnormalities in the blood. This panel includes: General Chemistry Screen or (SMAC), Complete Blood Count or (CBC), and Lipid examination. A 12 hour fast from all food and drink (water is allowed) is required to facilitate accurate results for some of the tests in this panel. Below, is a breakdown of all the components and a brief explanation of each test. Abnormal results do not necessarily indicate the presence of disease. However, it is very important that these results are interpreted by your doctor so that he/she can accurately interpret the findings in conjunction with your medical history and order any follow-up testing if needed. The Bernards Township Health Department and the testing laboratory cannot interpret these results for you. You must speak to your doctor! 262 South Finley Avenue Basking Ridge, NJ 07920 www.bernardshealth.org Phone: 908-204-2520 Fax: 908-204-3075 1 Chemistry Screen Components Albumin: A major protein of the blood, albumin plays an important role in maintaining the osmotic pressure spleen or water in the blood vessels. It is made in the liver and is an indicator of liver disease and nutritional status. A/G Ratio: A calculated ratio of the levels of Albumin and Globulin, 2 serum proteins. Low A/G ratios can be associated with certain liver diseases, kidney disease, myeloma and other disorders. ALT: Also know as SGPT, ALT is an enzyme produced by the liver and is useful in detecting liver disorders. -

Your Blood Cells

Page 1 of 2 Original Date The Johns Hopkins Hospital Patient Information 12/00 Oncology ReviseD/ RevieweD 6/14 Your Blood Cells Where are Blood cells are made in the bone marrow. The bone marrow blood cells is a liquid that looks like blood. It is found in several places of made? the body, such as your hips, chest bone and the middle part of your arm and leg bones. What types of • The three main types of blood cells are the red blood cells, blood cells do the white blood cells and the platelets. I have? • Red blood cells carry oxygen to all parts of the body. The normal hematocrit (or percentage of red blood cells in the blood) is 41-53%. Anemia means low red blood cells. • White blood cells fight infection. The normal white blood cell count is 4.5-11 (K/cu mm). The most important white blood cell to fight infection is the neutrophil. Forty to seventy percent (40-70%) of your white blood cells should be neutrophils. Neutropenia means your neutrophils are low, or less than 40%. • Platelets help your blood to clot and stop bleeding. The normal platelet count is 150-350 (K/cu mm). Thrombocytopenia means low platelets. How do you Your blood cells are measured by a test called the Complete measure my Blood Count (CBC) or Heme 8/Diff. You may want to keep track blood cells? of your blood counts on the back of this sheet. What When your blood counts are low, you may become anemic, get happens infections and bleed or bruise easier. -

Important Information for Female Platelet Donors

Important Information for Female Platelet Donors We are grateful for the support you provide our community blood program and especially appreciate your willingness to help save lives as a volunteer platelet donor. We also take our responsibility to provide a safe and adequate blood supply very seriously and need to share the following information regarding a change to our donor eligibility criteria for female platelet donors. We recently began performing a Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) antibody test on each of our current female platelet donors who have ever been pregnant. In addition, we modified our Medical History Questionnaire to ask donors whether they have been pregnant since their last donation. Platelet donors who respond yes to that question will be screened for HLA antibodies. Platelet donors will also be retested after every subsequent pregnancy. These adjustments are being made as part of our effort to reduce occurrences of Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI). TRALI is a rare but serious complication of blood transfusions most commonly thought to be caused by a reaction to HLA antibodies present in the donor’s plasma. When transfused, these antibodies can sometimes cause plasma to leak into the patient’s lungs, creating fluid accumulation — a condition referred to as acute pulmonary edema. Female donors who have been pregnant are more likely than others to have these HLA antibodies in their plasma. Once the antibodies develop, they are present forever. The antibodies could be harmful if transfused into certain patients. The antibodies are present in plasma — and platelet donations contain a high volume of plasma, so our current efforts are directed at screening blood samples from female platelet donors to test for the HLA antibody. -

FACTS ABOUT DONATING Blood WHY SHOULD I DONATE BLOOD? HOW MUCH BLOOD DO I HAVE? Blood Donors Save Lives

FACTS ABOUT DONATING BLOOD WHY SHOULD I DONATE BLOOD? HOW MUCH BLOOD DO I HAVE? Blood donors save lives. Volunteer blood donors provide An adult has about 10–11 pints. 100 percent of our community’s blood supply. Almost all of us will need blood products. HOW MUCH BLOOD WILL I donate? Whole blood donors give 500 milliliters, about one pint. WHO CAN DONATE BLOOD? Generally, you are eligible to donate if you are 16 years of WHAT HAPPENS TO BLOOD AFTER I donate? age or older, weigh at least 110 pounds and are in good Your blood is tested, separated into components, then health. Donors under 18 must have written permission distributed to local hospitals and trauma centers for from a parent or guardian prior to donation. patient transfusions. DOES IT HURT TO GIVE BLOOD? WHAT ARE THE MAIN BLOOD COMPONENTS? The sensation you feel is similar to a slight pinch on the Frequently transfused components include red blood arm. The process of drawing blood should take less than cells, which replace blood loss in patients during surgery ten minutes. or trauma; platelets, which are often used to control or prevent bleeding in surgery and trauma patients; and HOW DO I PREPARE FOR A BLOOD DONATION? plasma, which helps stop bleeding and can be used to We recommend that donors be well rested, eat a healthy treat severe burns. Both red blood cells and platelets meal, drink plenty of fluids and avoid caffeine and are often used to support patients undergoing cancer alcohol prior to donating. treatments. WHAT CAN I EXPECT WHEN I DONATE? WHEN CAN I DONATE AGAIN? At every donation, you will fill out a short health history You can donate whole blood every eight weeks, platelets questionaire. -

Community Lab Costs

Sickle Cell This tests for the genetic trait which may lead to sickle cell anemia. Osteoporosis Screening This uses ultrasound to screen people for low bone density or osteoporosis and is completed by painlessly scanning the heel. Because osteoporosis rarely causes signs or symptoms until it’s advanced, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends a bone density test if you are: • A woman older than age 65 or a man older than age 70 • A postmenopausal woman with at least one risk factor for osteoporosis Community Lab Costs • A man between age 50 and 70 who has at least one osteoporosis (greatly reduced rates) risk factor • Older than age 50 with a history of a broken bone • Taking medications, such as prednisone, aromatase inhibitors or Wellness Panel........................................................................ $20 Fasting anti-seizure drugs, that are associated with osteoporosis Includes screening for glucose, electrolytes, kidney, liver and • A postmenopausal woman who has recently stopped taking thyroid, plus complete blood count and lipid profile hormone therapy • A woman who experienced early menopause Diabetic Screening (A1c)...................................................... $5 The results of this test will indicate if you have or at risk for osteoporosis. Sickle Cell................................................................................ $6 If so, your doctor can offer treatment. PSA (Prostate Screening)...................................................... $8 Breathing Test This measures airflow and lung