Linking Communities, Tourism & Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Farmers and Shepherds to Shopkeepers and Hoteliers: Constituency-Differentiated Experiences of Endogenous Tourism in the Greek Island of Zakynthos

From Farmers and Shepherds to Shopkeepers and Hoteliers: Constituency-differentiated Experiences of Endogenous Tourism in the Greek Island of Zakynthos By: Yiorgos Apostolopoulos and Sevil F. Sönmez Apostolopoulos, Y. and S. Sönmez (1999). From Farmers and Shepherds to Shopkeepers and Hoteliers: Constituency-Differentiated Experiences of Endogenous Tourism in the Greek Isle of Zakynthos. International Journal of Tourism Research, 1(6):413-427. Made available courtesy of Wiley-Blackwell *** Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document *** Note: The definitive version is available at http://www3.interscience.wiley.com Abstract: The effects exerted by endogenous tourism investment on the developing Greek island of Zakynthos are examined, focusing in particular on whether the experiences among residents, tourist enterprises and local government are homogeneous, or whether they reflect varied attitudes related to sociodemographic, destination, development-process and tourist characteristics. Multivariate analysis shows that the main factors contributing to the variance in locals' experiences of and reactions to tourism development are the endogenous nature associated with the early 'development' phase of the evolution cycle, inhabitant constituency, carrying capacity and tourist nationality. In addition, the protection and conservation of natural and sociocultural resources are revealed as serious concerns of the island's local government. Management strategies for visitor-impact alleviation should focus on community-based -

Sustainability Issues of Health Tourism Non-Profit- Organisations

African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, Volume 8 (5) - (2019) ISSN: 2223-814X Copyright: © 2019 AJHTL /Author/s- Open Access- Online @ http//: www.ajhtl.com Sustainability issues of health tourism Non-Profit- Organisations Chux Gervase Iwu* Department of Entrepreneurship and Business Management Faculty of Business and Management Sciences Cape Peninsula University of Technology Cape Town, South Africa Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Prominent Choto Department of Marketing Faculty of Business and Management Sciences Cape Peninsula University of Technology South Africa Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Robertson Khan Tengeh Department of Entrepreneurship and Business Management Faculty of Business and Management Sciences Cape Peninsula University of Technology Cape Town, South Africa Email: [email protected] Corresponding author* Abstract Health tourism occurs when people around the world travel across international borders to access various health and wellness treatment and at the same time touring the country they are visiting. It is one of the growing industries in South Africa, as people are constantly coming to South Africa in search of health care services. Health tourism is imperative for economic growth and development and has recently assumed the status of one of the most important contributors to employment, infrastructural and services development, and generating an economic return. Due to these significant contributions, it is vital to have sustainable health care services in countries attracting health tourists. Making use of the traditional literature method, this paper presents an overview of health tourism, the importance of healthcare in South Africa, discussing the sustainability issues faced by health care providers and the impact thereof to health tourism. -

Research on the Industrial Integration of the Tourism Industry in Xi'an from the Panoramic View

2018 5th International Conference on Business, Economics and Management (BUSEM 2018) Research on the Industrial Integration of the Tourism Industry in Xi’an from the Panoramic View Jian Xin Xi’an International Studies University, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710128 Keywords: panoramic view; Xi’an tourism; industrial integration Abstract: In order to make an overall developmental planning for taking advantage of tourist resources and promote the development of the tourism industry of Xi’an, it is necessary to research the industrial integration model of Xi’an from the panoramic view, and to integrate the cultural tourism, the sports tourism, the agricultural tourism, and the other industries systematically such as agriculture industry, primary industry, financial industry, information industry; it is also necessary to make a perfect macro adjusting and controlling planning of the tourism industry in Xi’an so as to promote the tourism industry in future. According to relevant documents, this paper researches the industrial integration model of tourism so as to solve some problems in the development of Xi’an tourism industry. As the development of economy and relevant policies, at the present stage, the tourism industry of Xi’an has been greatly developed than before, however, as its further development, there are still many actual dilemmas. During the development of the tourism industry, it is lack of scientific and overall planning, and the integration among the different industries is seriously insufficient, and the standard industrial chain has not been formed, and these factors have badly restricted the sustainable development of tourism industry in Xi'an. In order to optimize the industrial developmental structure of the tourism industry in Xi’an, it is necessary to develop the tourism industry of Xi’an from the panoramic view, and to research the industrial integration model of the tourism industry in Xi’an systematically, so as to find out the appropriate developmental path for the tourism industry in Xi’an and promote the further development of the local economy. -

Unit 5 Constituents of Tourism Industry and Tourism Organisations

UNIT 5 CONSTITUENTS OF TOURISM INDUSTRY AND TOURISM ORGANISATIONS Structure 5.0 Objectives 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Tourism Industry 5.3 Constituents 5.3.1 Primary/Major Constituents 5.3.2 Secondary Constituents 5.4 Tourism Organisations 5.5 International Organisations 5.5.1 WTO 5.5.2 Other Organisations 5.6 Government Organisations in India 5.6.1 Central Government \J 5.6.2 State Government/Union Territories • 5.7 Private Sector Organisations in India 5.7.1 IATO 5.7.2 TAAI 5.7.3 FHRAI 5.8 Let Us Sum Up 5.9 Keywords 5.10 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 5.0 OBJECTIVES After reading this Unit you will be able to : • understand why tourism is being called an industry, • know about the various constituents of the Tourism Industry, • learn about the interdependence of its various constituents, • familiarise yourself with various types of tourism organisations, • learn about the functions and relevance of some of these organisations, and • list such questions about the Tourism Industry that tourism professionals should be able to answer when required. 5.1 INTRODUCTION The tourism of today 'is the outcome of the combined efforts of its various constituents. There are possibilities of more constituents being attached in the future. In fact what we may define as Tourism Industry is a mix of the output and services of different industries and services. This Unit begins with a theoretical discussion on tourism being described as an industry. It goes on to -identify and list its various constituents. However, their description is confined to a brief discussion as most of them have been independently discussed in individual Units. -

Maui County Tourism Industry Strategic Plan 2017-2026 Maui County Tourism Industry Strategic Plan 2017-2026

MAUI COUNTY TOURISM INDUSTRY STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2026 Volume 1: Maui County Tourism Overview and Plan Maui County Tourism Industry Strategic Plan 2017-2026 Maui County Tourism Industry Strategic Plan 2017-2026 Contents I. Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 1 II. Introduction and Background ............................................................................ 5 A. Purpose of the Plan .................................................................................................................. 5 B. State and County Plans ............................................................................................................ 6 C. Development Process .............................................................................................................. 6 D. Guiding Principles .................................................................................................................... 6 E. Implementation Framework .................................................................................................... 7 III. Overview of Tourism ......................................................................................... 8 A. State Level ................................................................................................................................ 8 1. Historical Trends ................................................................................................................ 8 2. Vital Issues Facing Hawai‘i -

U.S. Travel and Tourism and COVID-19

INSIGHTi U.S. Travel and Tourism and COVID-19 April 10, 2020 With the spread of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, many flights have been canceled, widespread travel bans have been put in place, and more quarantine and stay-at-home orders are in effect. This has sharply reduced domestic and international travel, prompting businesses across the U.S. travel sectors to ask the U.S. government for financial assistance. For Congress, this raises questions about the likely economic effects of COVID-19 on travel and tourism and the level of support warranted for some industry segments that may quickly recover once the pandemic subsides and businesses reopen. U.S. Travel and Tourism The nation’s travel and tourism industries are an amalgam of business activities including transportation, lodging, entertainment, and meals. According to government data, U.S. travel and tourism accounted for 2.9% of U.S. gross domestic product in 2018. Because the travel and tourism economy is particularly labor-intensive—directly employing 5.9 million workers in 2018—it ranks among the hardest-hit industries from the coronavirus’s spread. The last sharp decline in tourism employment was during the three-year period 2007-2009, when the industry shed more than 680,000 jobs (see Figure 1). Nationwide, in 2018, average compensation per tourism employee in food services—the largest category of travel and tourism employment—was $26,000, and in traveler accommodations was $43,000. These two segments jointly account for more than half of all jobs in the sector, many of which are seasonal or part-time and require fewer skills than other industries. -

The Effects of Travel and Tourism on California's Economy: a Labor

The Effects of Travel and Tourism on California’s Economy A Labor Market–Focused Analysis Matthew D. Baird, Edward G. Keating, Olena Bogdan, Adam C. Resnick C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1854 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication ISBN: 978-0-8330-9736-1 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: GettyImages/davemantel. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Visit California, a 501(c)6 nonprofit corporation formed in 1998 to market California as a desirable tourism destination, asked the RAND Corporation to estimate the effects of travel/ tourism on the state’s economy. -

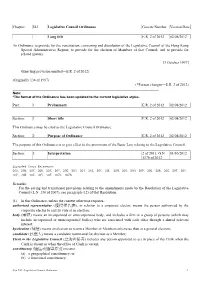

Constituency (選區或選舉界別) Means- (A) a Geographical Constituency; Or (B) a Functional Constituency;

Chapter: 542 Legislative Council Ordinance Gazette Number Version Date Long title E.R. 2 of 2012 02/08/2012 An Ordinance to provide for the constitution, convening and dissolution of the Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; to provide for the election of Members of that Council; and to provide for related matters. [3 October 1997] (Enacting provision omitted—E.R. 2 of 2012) (Originally 134 of 1997) (*Format changes—E.R. 2 of 2012) _______________________________________________________________________________ Note: *The format of the Ordinance has been updated to the current legislative styles. Part: 1 Preliminary E.R. 2 of 2012 02/08/2012 Section: 1 Short title E.R. 2 of 2012 02/08/2012 This Ordinance may be cited as the Legislative Council Ordinance. Section: 2 Purpose of Ordinance E.R. 2 of 2012 02/08/2012 The purpose of this Ordinance is to give effect to the provisions of the Basic Law relating to the Legislative Council. Section: 3 Interpretation 2 of 2011; G.N. 01/10/2012 5176 of 2012 Expanded Cross Reference: 20A, 20B, 20C, 20D, 20E, 20F, 20G, 20H, 20I, 20J, 20K, 20L, 20M, 20N, 20O, 20P, 20Q, 20R, 20S, 20T, 20U, 20V, 20W, 20X, 20Y, 20Z, 20ZA, 20ZB Remarks: For the saving and transitional provisions relating to the amendments made by the Resolution of the Legislative Council (L.N. 130 of 2007), see paragraph (12) of that Resolution. (1) In this Ordinance, unless the context otherwise requires- authorized representative (獲授權代表), in relation to a corporate elector, means the person authorized by the -

Candidate Profile Booklet

APPROVED RT011 Page 2 Table of Contents Disclaimer Page 2 Voting Instructions Page 3 to 5 Rotorua District Council (operating as Rotorua Lakes Council) Electing the Mayor Page 6 Rotorua District Council Councillor At Large Electing 10 Councillors Page 10 Rotorua District Council Rotorua Lakes Community Board Electing 4 Members Page 28 Rotorua District Council Rotorua Rural Community Board Electing 4 Members Page 32 Bay of Plenty Regional Council Rotorua General Constituency Electing 2 Regional Councillors Page 35 Waikato Regional Council Waihou General Constituency Electing 2 Regional Councillors Page 37 Waikato Regional Council Taupo-Rotorua General Constituency Electing 1 Regional Councillor Page 40 Lakes District Health Board ElectingAPPROVED 7 Members Page 42 Disclaimer This candidate directory has been compiled under the Local Electoral Act 2001. The Act provides that an electoral officer is not required to verify or investigate any information included in candidate profile statements and is not responsible for the accuracy of the information contained in such statements. Page 3 1. Vote Follow the instructions on your voting document. VOTE. PACK. POST. THREE EASY STEPS TO COMPLETE YOUR POSTAL VOTING. 2. Pack Put your voting document in the APPROVEDorange return envelope. 3. Post Seal the orange envelope and post To find a nearby Post Box or deliver. Scan QR Barcode or go to http://bit.ly/FINDPOST Page 4 WHAT POSITIONS ARE UP FOR ELECTION We hope you’ll vote in all elections on your voting document – the successful candidates make decisions that affect us all every day so make sure you have your say. You may find all or some of these positions on your voting document: 1) The Mayor is the leader of the City or District Council. -

Medical Tourism: Medical Tourism

MMeeddiiccaall TToouurriissmm:: IImmpplliiccaattiioonnss ffoorr PPaarrttiicciippaannttss iinn tthhee UUSS HHeeaalltthh CCaarree SSyysstteemm October 2007 MEDPHARMA PARTNERS LLC & MEDTRIPINFO.COM 101 Federal St., S. 1900 Boston, MA 02110 www.mppllc.com www.MedTripInfo.com David E. Williams John Seus [email protected] [email protected] (617) 731-3182 (978) 281-6705 Medical Tourism: Implications for Participants in the US Health Care System Table of Contents Introduction ..........................................................................2 Five predictions about medical tourism ...............................3 Issues for US industry participants......................................6 Health plans and employers..............................................6 Health care providers ........................................................8 Medical device companies ..............................................10 Pharmaceutical companies .............................................12 Conclusions .......................................................................13 For further information .......................................................13 Medical Tourism – Implications for participants in the US health care system p. 1 ©2007, MedPharma Partners LLC, www.mppllc.com, (617) 648-3828 Medical Tourism – Introduction Why Medical Tourism Deserves Attention Now… • US patients are discovering high quality, low cost care and excellent customer service in overseas locations. Cost savings range as high as 60 to 90 percent. • Increasingly, -

MADE in AMERICA: MEDICAL TOURISM and BIRTH TOURISM LEADING to a LARGER BASE of TRANSIENT CITIZENSHIP Tyler Grant* INTRODUCTION

MADE IN AMERICA: MEDICAL TOURISM AND BIRTH TOURISM LEADING TO A LARGER BASE OF TRANSIENT CITIZENSHIP Tyler Grant* INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 160 I. BIRTH TOURISM: DUAL-CITIZENRY THROUGH A LOOPHOLE? ....... 161 A. The “Loophole” in the Fourteenth Amendment and How the United States Has Responded to It .......................................... 163 B. U.S. Immigration Implications ................................................ 168 C. The Effect of Taiwan Birth Tourism ......................................... 169 II. TAIWAN MEDICAL TOURISM: AN EMERGING MARKET .................. 170 A. At an Economic and Social Crossroads: Where Medical and Birth Tourism Intersect ............................................................ 174 B. Possible Policy Outcomes to Balance U.S.-Taiwan Migration in Healthcare and Birth Tourism ............................ 176 CONCLUSION ......................................................................................... 177 * J.D. Candidate, 2016, University of Virginia School of Law. I am grateful to my friends and colleagues in Taiwan who have given me the passion to pur- sue this topic and the endurance to continue to chase greater ideas and bridge cultures. And I am thankful to my family for their continued support during my academic career and to Professor Thomas A. Massaro for his guidance and ex- pansion of my notions of global interconnectedness and of how classroom ideas can lead to global solutions. 160 Virginia Journal of Social Policy & the Law [Vol. 22:1 MADE IN AMERICA: MEDICAL TOURISM AND BIRTH TOURISM LEADING TO A LARGER BASE OF TRANSIENT CITIZENSHIP Tyler Grant Transnationalism has become a much larger issue as international travel has increased, and countries are incentivized to ease border controls in order to boost their economies. At times, this comes at a cost. Birth tourism and medical tourism are becoming trends in the United States and Taiwan and are producing differing consequences that policymakers will have to address. -

MASTER PLANNING for TOURISM in MICHIGAN Belle Isle State Park

MASTER PLANNING FOR TOURISM IN MICHIGAN Belle Isle State Park. Photo courtesy of MDNR. Master Planning for Tourism in Michigan was produced by the Michigan Association of Planning, a chapter of the American Planning Association, in June 2020. PROJECT TEAM ANDREA BROWN, AICP, Executive Director Michigan Association of Planning WENDY RAMPSON, AICP, Director of Programs and Outreach Michigan Association of Planning MATT SMAR, Water Resources Division Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy SARAH NICHOLLS, PhD, Professor & Chair in Placemaking and Destination Management Swansea University THOMAS MCKEE, Intern Michigan Association of Planning MRITHULA SHANTHA THIRUMALAI ANANDANPILLAI, Intern Michigan Association of Planning MATT COWALL, Acting Executive Director Land Information Access Association JIM MURATZKI, Technology Director Land Information Access Association ZACHARY VEGA, Community Planner Land Information Access Association Graphic design provided by Kaye Krapohl, Designer Land Information Access Association To cite this work: Rampson, W., & Nicholls, S. (Eds.) (2020). Master Planning for Tourism in Michigan. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Association of Planning Financial assistance for this project was provided, in part, by the Coastal Management Program, Water Resources Division, Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy, under the National Coastal Zone Management Program, through a grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations in this document are those of the Michigan Association of Planning and individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Cover photo: Kayaker by Finn Terman Frederiksen ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The creation of this guide would not have been possible without the expertise, insights, knowledge and passion of the many contributors.