Of Gaps and Ghosts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

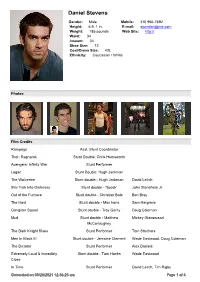

Daniel Stevens

Daniel Stevens Gender: Male Mobile: 310 956-7692 Height: 6 ft. 1 in. E-mail: [email protected] Weight: 185 pounds Web Site: http:// Waist: 34 Inseam: 34 Shoe Size: 12 Coat/Dress Size: 42L Ethnicity: Caucasian / White Photos Film Credits Rampage Asst. Stunt Coordinator Thor: Ragnarok Stunt Double: Chris Hemsworth Avengers: Infinity War Stunt Performer Logan Stunt Double: Hugh Jackman The Wolverine Stunt double - Hugh Jackman David Leitch Star Trek Into Darkness Stunt double - 'Spock' John Stoneham Jr. Out of the Furnace Stunt double - Christian Bale Ben Bray The Host Stunt double - Max Irons Sam Hargrave Gangster Squad Stunt double - Troy Garity Doug Coleman Mud Stunt double - Matthew Mickey Giacomazzi McConaughey The Dark Knight Rises Stunt Performer Tom Struthers Men In Black III Stunt double - Jemaine Clement Wade Eastwood, Doug Coleman The Dictator Stunt Performer Alex Daniels Extremely Loud & Incredibly Stunt double - Tom Hanks Wade Eastwood Close In Time Stunt Performer David Leitch, Tim Rigby Generated on 09/26/2021 12:36:25 am Page 1 of 3 Jack Gill, Daniel Stevens Green Lantern Stunt double - Ryan Reynolds Gary Powell Unstoppable Stunt double - Chris Pine Gary Powell Warrior Stunt Performer J.J. Perry The Expendables Stunt Performer Chad Stahelski X-Men Origins: Wolverine Stunt double - Hugh Jackman J.J. Perry, Chad Stahelski Takers Stunt Performer Lance Gilbert Angel of Death Stunt Performer Ron Yuan Once Fallen Stunt double - Peter Greene Noon Orsatti Iron Man Stunt double - 'Iron Man' Tom Harper, Keith Woulard Midnight Meat Train Stunt double - Vinnie Jones David Leitch Where The Wild Things Are Stunt double - 'Judith' Darrin Prescott Suffering Man's Charity Stunt double - Alan Cumming Nick Plantico Crank Stunt Performer Darrin Prescott Ravenswood Stunt double - Travis Fimmel Richard Boue Superman Returns Stunt Performer R.A. -

Mid-Season-Lineup-Release Final

GLOBAL RINGS IN 2017 WITH STELLAR MIDSEASON PRIMETIME LINEUP Network Celebrates the New Year with the Premiere of New Canadian Drama Ransom on January 1 Compelling New Original Drama Mary Kills People Joins Global’s Schedule January 25 Additional New Series The Blacklist: Redemption and Chicago Justice Join New Episodes of Fall’s Breakout Hits and New Seasons of Returning Favourites For additional photography and press kit material visit: http://www.corusent.com To view Global’s midseason and original series Ransom promos: Midseason Promo and Ransom Promo To share this release socially: http://bit.ly/2h6e7Up For Immediate Release TORONTO, December 20, 2016 – Coming off of a highly successful fall season with three of the top five new fall series, Global rings in 2017 with a robust midseason primetime lineup. The network heads into the winter season with a schedule packed with Canada’s most-watched programing including this season’s most-anticipated new and returning series. Kicking off the New Year are two new Canadian original drama series. Inspired by the professional experiences of distinguished crisis negotiator Laurent Combalbert, comes Ransom, a high stakes suspense drama premiering on Sunday, January 1 at 8:30 p.m. ET/8 p.m. PT on Global. Starring Luke Roberts (Wolf Hall, Game of Thrones), as Eric Beaumont, a crisis and hostage negotiator whose team is brought in to save lives when no one else can, the series moves to Wednesdays at 8 p.m. ET/PT starting January 4 and Saturdays at 8 p.m. ET/PT beginning January 7. Then, Global’s compelling, new character-driven drama Mary Kills People joins the schedule Wednesday, January 25 at 9 p.m. -

10 BOLD Feb 7

Firefox http://prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Repor... SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 07th February 2021 06:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 06:30 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:30 am Key Of David PG The Key of David, a religious program, covers important issues of today with a unique perspective. 08:00 am Roads Less Travelled (Rpt) CC PG An Australian Road Trip Series exploring those hidden gems that only the locals know about. Tour some of the lesser known roads exploring unique locations amidst Australia’s natural beauty. 08:30 am Mega Mechanics (Rpt) G What happens when mega-machines go down? It's up to the mega- mechanics to fix them! With huge structures, extreme locations & millions of dollars on the line if they don't repair the machines on time. 09:30 am One Strange Rock (Rpt) CC G Escape Astronaut Chris Hadfield has seen the bullet holes left by asteroids on Earth's surface. Our planet is vulnerable. Could we ever survive elsewhere? 10:30 am Escape Fishing With ET (Rpt) CC G Escape with former Rugby League Legend "ET" Andrew Ettingshausen as he travels Australia and the Pacific, hunting out all types of species of fish, while sharing his knowledge on how to catch them. 11:00 am Scorpion (Rpt) CC PG Revenge Violence, Sylvester is seriously injured when he accidentally triggers an explosive Coarse Language device during an investigation and Team Scorpion search for who is responsible. Starring: Elyes Gabel, Katharine McPhee, Robert Patrick, Ari Stidham, Eddie Kaye Thomas, Jadyn Wong 12:00 pm Scorpion (Rpt) CC PG Dominoes Mature Themes Team Scorpion try to save a boy on Christmas Eve when he gets trapped in a beach-side cave and the rising tide threatens to drown him. -

The Oxford Democrat: Vol. 63, No. 10

The Oxford Democrat. 10,189β. NUMBER 10. VOLUME 63. SOUTH PARIS, MAINE, TUESDAY, M^RCH and auotiier of ana a vari- where do man walked abroad without OF THE GREAT NORTHWEST. milk aorgnum Written for the Oxford Democrat. ONE OF THE DUPES INDIANS SAVING THE PIGS. within the settle- ety of hotcnru broad called "cracklina," bin rifle ou bin shoulder, ao after break ,,ΚθΚ».ΚΡ mi-SHKM.. SOUL. Ttu real dwellers ΤΗ Κ FARMERS. on the farm there are THE CONCORD OF BODY AND AMONG Every spring ment >f the Hudson are enriched by tiny bit* at fresh pork, f;iht Tom took down h», and we fell in (ι DEFEND "WOMAN'S LOVK KO Bay Company either not endowed with a RISES TO chief- the care to at Law, certaiu'pigs a com [Mratlve handful, comprising chopped âne aud scattered through it bin heel*, taking good k*«p Counsellor "irill) Τ U I PLOW." (air *hare of or too BEAUTIFUL." serv- physical vigor, Oh how deep deception· govern men' THE ly the miss'on people, the company loaf. MAINE numerous brothers and sWters crowd The body in lieu of the neart, as those Lieutenant V. H. 8HELT0I. FALLS, do and a few '"freemen," Bj No one conld ns much informa- Kl'VroRD aud Through our liodles we love, while heart· sot ants, give on aerlruUur·1 them aside. grow weaker enlist- i'orr»pon<l«»c« prmrtkal loplo· They •ee Editor Drmotrat : whot »ve served their Ave years' tion about the road to the mountain*, le *»n«n«M Α·Μττ»» all n>mmunk-aUoa»la- weaker and or become misera- ·. -

Jephthah's Daughter in American Jewish Women's Poetry

Open Theology 2020; 6: 1–14 Women and Gender in the Bible and the Biblical World Anat Koplowitz-Breier* A Nameless Bride of Death: Jephthah’s Daughter in American Jewish Women’s Poetry https://doi.org/10.1515/opth-2020-0001 Received September 5, 2019; accepted November 8, 2019 Abstract: In the Hebrew Bible, Jephthah’s daughter has neither name nor heir. The biblical account (Judg. 11:30–40) is somber—a daughter due to be sacrificed because of her father’s rash vow. The theme has inspired numerous midrashim and over five hundred artistic works since the Renaissance. Traditionally barred from studying the Jewish canon as women, many Jewish feminists are now adopting the midrashic- poetry tradition as a way of vivifying the female characters in the Hebrew Bible. The five on which this article centers focus on Jephthah’s daughter, letting her tell her (side of the) story and imputing feelings and emotions to her. Although not giving her a name, they hereby commemorate her existence—and stake a claim for their own presence, autonomy, and active participation in tradition and society as Jewish women. Keywords: Jephthah’s daughter, American Jewish women’s poetry, midrash, midrashic poetry, contemporary poetry In the Hebrew Bible, Jephthah’s daughter has neither name nor heir. Even the statement that it became a custom in Israel “for the maidens of Israel to go every year, for four days in the year, and chant dirges for the daughter of Jephthah the Gileadite” (Judg. 11:40) finds no trace in later Jewish halakhic tradition.1 The view that a nameless figure is not a full person evidently reaches far back into history.2 More recently, Adele Reinhartz has adduced four functions proper names play in the biblical text: First, the proper name in itself may carry meaning. -

Star Channels Guide, August 6-12

AUGUST 6 - 12, 2017 staradvertiser.com MR. FIXIT The new season of Ray Donovan sees the titular Ray (Liev Schreiber, “X-Men Origins: Wolverine”) turn his attention back to his celebrity fi xer fi rm after a shift of focus in season 4. This year, a major client is played by a major talent: look for Oscar winner Susan Sarandon (“Thelma & Louise”) in a recurring role in season 5. Airs Sunday, Aug. 6, on Showtime. – ¶Olelo’s video competition is a celebration for each student’s hard work. LUANE HIGUCHI%=b`bmZeF^]bZM^Z\a^k%PZbZgZ^Bgm^kf^]bZm^ From the annual Youth Xchange Student Video Competition to the year-round after school 49 52 53 54 55 programs, ¶ Şe^eha^eilm^Z\a^kl^fihp^kma^bklmn]^gmlmh^g`Z`^ma^bk\hffngbmr' www.olelo.org ON THE COVER | RAY DONOVAN ‘Ray’ of light Susan Sarandon joins a darker Things were looking good for the Donovans most recent of which could very well turn into a at the end of last season. Ray avoided prison, win in September. season 5 of ‘Ray Donovan’ and we were even granted an unusually light- It’s not just Schreiber who has seen success hearted scene of him playing video games from the show. “Ray Donovan” opened to re- By Jacqueline Spendlove with his kids. His wife, Abby (Paula Malcomson, cord-breaking numbers, becoming Showtime’s TV Media “Deadwood”), announced that her cancer is biggest premiere of all time. It’s won a Critics’ gone, and that she wants the two of them to Choice Television Award, a Golden Globe and an ho knew rich and glamorous celebri- make a fresh start, while his daughter, Bridget Emmy, among its many nominations, and aver- ties had so many hush-hush prob- (Kerris Dorsey, “Brothers & Sisters”), was ac- aged 1.2 million viewers last season. -

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Peters Township School District MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR READING LEVEL POINTS I Had A Hammer: Hank Aaron... Aaron, Hank 7.1 34 Postcard, The Abbott, Tony 3.5 17 My Thirteenth Winter: A Memoir Abeel, Samantha 7.1 13 Go And Come Back Abelove, Joan 5.2 10 Saying It Out Loud Abelove, Joan 5.8 8 Behind The Curtain Abrahams, Peter 3.5 16 Down The Rabbit Hole Abrahams, Peter 5.8 16 Into The Dark Abrahams, Peter 3.7 15 Reality Check Abrahams, Peter 5.3 17 Up All Night Abrahams, Peter 4.7 10 Defining Dulcie Acampora, Paul 3.5 9 Dirk Gently's Holistic... Adams, Douglas 7.8 18 Guía-autoestopista galá.... Adams, Douglas 8.1 12 Hitchhiker's Guide To The... Adams, Douglas 8.3 13 Life, The Universe, And... Adams, Douglas 8.6 13 Mostly Harmless Adams, Douglas 8.5 14 Restaurant At The End-Universe Adams, Douglas 8.1 12 So Long, And Thanks For All Adams, Douglas 9.4 12 Watership Down Adams, Richard 7.4 30 Storm Without Rain, A Adkins, Jan 5.6 8 Thomas Edison (DK Biography) Adkins, Jan 9.4 8 Ghost Brother Adler, C. S. 6.5 7 Her Blue Straw Hat Adler, C. S. 5.5 9 If You Need Me Adler, C. S. 6.9 7 In Our House Scott Is My... Adler, C. S. 7.2 8 Kiss The Clown Adler, C. S. 6.1 8 Lump In The Middle, The Adler, C. S. 6.5 10 More Than A Horse Adler, C. -

See What's on ¶O – Lelo This Week, This Hour, This Second

AUGUST 27 - SEPTEMBER 2, 2017 staradvertiser.com GAME ON Michael Strahan (“Good Morning America”) hosts as celebrities team up with contestants to play word-association games in the hopes of winning cash in a new episode of The $100,000 Pyramid. This week’s celebrity guests include NASCAR champ Kyle Busch, Strahan’s “Good Morning America” colleague Lara Spencer, rapper-turned-actor Ice-T (“Law & Order: Special Victims Unit”) and actress Peri Gilpin (“Frasier”). New episode Sunday, Aug. 27, on ABC. – See what’s on ROlelo this week, this hour, this second. View our online TV schedule at olelo.org/tv 49 52 53 54 55 www.olelo.org ON THE COVER | THE $100,000 PYRAMID From talk to games Michael Strahan touches down as want to watch a kids show, and as a kid you one contestant take turns giving each other host of ‘The $100,000 Pyramid’ probably don’t want to watch a big, serious clues to items in a chosen category, with a adult show. Here is something you can watch point awarded for each right answer. After together.” three rounds of play, the team with the most By Kyla Brewer This is the second season of the revamped points advances to the Winner’s Circle to play TV Media game show, which debuted on CBS in 1973 as for the big prize. The new ABC series features “The $10,000 Pyramid” before jumping to ABC an hour-long format, which allows enough time rime time has gone retro once again. A in 1974, with television icon Dick Clark at the for two complete games. -

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Peters Township School District MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR READING LEVEL POINTS Abduction, The Korman, Gordon 4 7 After The War Matas, Carol 5.5 7 Alice In April Naylor, Phyllis Reynolds 5.4 7 Alice The Brave Naylor, Phyllis Reynolds 5.2 7 All-Of-A-Kind Family Taylor, Sydney 4.5 7 Amazing But True Sports Storie Hollander, Phyllis 6.1 7 Animal Family, The Jarrell, Randall 4.6 7 Another Day Sachs, Marilyn 5.5 7 Antarctica (Myers) Myers, Walter Dean 8.6 7 Anthem Rand, Ayn 7.9 7 Arly Peck, Robert Newton 6.8 7 Arnold Schwarzenegger (Sexton) Sexton, Colleen 7.1 7 Ashwater Experiment, The Koss, Amy Goldman 6.4 7 Bad Beginning, The Snicket, Lemony 6.1 7 Badger On The Barge & Other... Howker, Janni 6.9 7 Bagthorpes V. The World Cresswell, Helen 6.9 7 Beowulf The Warrior Serraillier, Ian 8.3 7 Beowulf: A New Telling Nye, Robert 5.5 7 Bird Johnson, Angela 4.5 7 Birthday Murderer Bennett, Jay 5.1 7 Black Gold Henry, Marguerite 4.2 7 Black Pearl, The O'Dell, Scott 5.3 7 Blind Date Stine, R. L. 4.4 7 Bone Dance Brooks, Martha 5.9 7 Bone: Eyes Of The Storm Smith, Jeff 3.6 7 Book Of Changes Wynne-Jones, Tim 5.3 7 Book Of Nightmares Peel, John 5.2 7 Book Of Signs Peel, John 5.8 7 Borrowers, The Norton, Mary 4.8 7 Boy In The Moon, The Koertge, Ron 6.7 7 Branded Outlaw Hubbard, L. -

QUARANTINE EDITION CAPTURED WORDS/FREE THOUGHTS Volume 17, Winter 2021 —Writing and Art from America’S Prisons—

Captured Words/Free Thoughts Volume 17 Winter 2021 QUARANTINE EDITION CAPTURED WORDS/FREE THOUGHTS Volume 17, Winter 2021 —Writing and Art from America’s Prisons— Captured Words/Free Thoughts offers testimony from America’s prisons and prison-impacted communities. This issue includes poems, stories, letters, essays, and art made by men and women incarcerated in California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, Mississippi, Nebraska, North Carolina, New Jersey, Utah, Texas, and Wisconsin. To expand the scope of our project, we also include works made by folks on the free side of the prison walls whose lives have been impacted by crime, violence, and the prison industrial- complex. Volume 17 was compiled and edited by Benjamin Boyce, Meghan Cosgrove, Stephen J. Hartnett, and Vincent Russell. Layout, design, and this volume’s gorgeous photography were all handled by Andrei Howell. MISSION STATEMENT We believe reducing crime and reclaiming our neighborhoods depends in part on enabling a generation of abandoned Americans to experience different modes of citizenship, self-reflection, and personal expression. Captured Words/ Free Thoughts therefore aspires to empower its contributors, to enlighten its readers, and to shift societal perception so that prisoners are viewed as talented, valuable members of society, not persons to be feared. We believe in the humanity, creativity, and indomitable spirit of each and every one of our collaborators, meaning our magazine is a celebration of the power of turning tragedy into art, of using our communication skills to work collectively for social justice. THANKS · Thanks to the CU Denver Department of Communication Chair, Dr. Lisa Keränen, for her support for this project. -

Sports 1:11:07 Pg 1

FREE PRESS SSSPORTSPORTS Page 8 Colby Free Press Thursday, January 11, 2007 TV LISTINGS sponsored by the COLBY FREE PRESS SATURDAY JANUARY 13 6 AM 6:30 7 AM 7:30 8 AM 8:30 9 AM 9:30 10 AM 10:30 11 AM 11:30 KLBY/ABC Good Morning Good Morning Good Morning That’s- That’s- Hannah Zack & Emperor Replace- H h Kansas Saturday America (CC) Kansas Saturday Raven Raven Montana Cody New ments KSNK/NBC Today (CC) Paid Paid Babar Dragon 3 2 1 Pen Veggie- Jane- Jacob L j Program Program (EI) (CC) (EI) (CC) Tales Dragon Two Two KBSL/CBS Saturday Early Show (CC) News Cake (EI) Dance Paid Paid 1< NX (CC) Revolut. Program Program K15CG Busi- Market- Mister Thomas- Jay Jay Bob the Signing Dragon- Real Holiday Bake Victory d ness Market Rogers Friends the Jet Builder Time! flyTV Moms Table Decorate Garden ESPN Sports- SportsCenter (CC) NFL SportsCenter (CC) SportsCenter (Live) Sunday NFL College Basketball: O_ Center Matchup (CC) Countdown (Live) W.Va. at Marquette USA Paid Paid Paid Paid Nashville Star (CC) Coach Movie: Head Over Heels TZ (2001, Psych P^ Program Program Program Program (CC) Romance-Comedy) Monica Potter. (CC) Pilot (CC) TBS Steve Steve Movie: Baby Boom TTT (1987, Comedy) Movie: Sugar & Spice TTZ (2001, Movie: Clueless P_ Harvey Harvey Diane Keaton, Harold Ramis. (CC) Comedy) Marley Shelton. (CC) TTT (1995) (CC) WGN Enter- Adelante Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid HomeTeam Pa prise Chicago Program Program Program Program Program Program Program Program Minneapolis (CC) TNT Movie: 3000 Miles to Graceland TT (2001) Fake Movie: Get Carter (2000) A mob enforcer Movie: Assassins TT (1995, QW Elvis impersonators stage a casino heist in Las Vegas. -

(ED), Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 221 416 $0 014 047 AUTHOR Wead, Margaret TITLE 'Six American Histories. INSTITUTION Education Service Center Region 2, Corpus Christi, Tex. SPONS AGENCY Office of Elementary and Secondary Education (ED), Washington, DC. Ethnic Heritage Studies Program. 'PUB DATE Nov 81 GRANT GO00005189 NOTE 293p.; Some p)ges may not reproduce clearly, due to light print typthroughout original document. Best copy available. EDRS PRICE MF.01/PC12 Pl4k Postage. DESCRIPTORS Black HistoryiT Elementary Secondary Education; *Ethnic Studies; *History; Jews; Mexican Americans; Polish Americans; Resource Materials; *Social Studies; State History; United States History IDENTIFIERS Czech Americans; German Americans; Holidays; Texas ABSTRACT Histories of Blacks, Czechs, Germans Jews, Mexicans, and Poles are provided in this resource guide. The his ries are intended as a major background resource to help instructronal staff members of the 45 school systems in Edtication'Service Center, Region II, Corpus Christi, Texas, integrate ethnic heritage studies materials into classroom instruction. The history of each group begins with a brief description of contributions, customs, and factsij A detailed narrative, which often quotes peimary source ritterials, follows. The section on Black history contains a'list of important dates. The sections on Blacks, Czechs, and Jews, in adclition to describing the general histories of these groups, also discuss their histories and experiences in Texas. Also included in the guide are a calendar of ethnic holidays and a bibliography of additional resource materials. (RM) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ************************,****i****************************************** go, z 14+, ETHNIC HERITAGE STUDIES U S DEPARTMENTOF EDUCATION OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE INF 71;MA 11()N WI( A TIONAI R011Nt k 1111( WrItilil it,q II Ellprt., II I,tIlerli), lilt1, NIII1,1 i 11,111IP:.