One More Miracle the Memoirs of Morris Sorid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super! Drama TV August 2020

Super! drama TV August 2020 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2020.08.01 2020.08.02 Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 Season 5 Season 5 #10 #11 06:30 06:30 「RAPTURE」 「THE DARKNESS AND THE LIGHT」 06:30 07:00 07:00 07:00 CAPTAIN SCARLET AND THE 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 MYSTERONS GENERATION Season 6 #19 「DANGEROUS RENDEZVOUS」 #5 「SCHISMS」 07:30 07:30 07:30 JOE 90 07:30 #19 「LONE-HANDED 90」 08:00 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN TOWARDS THE 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 FUTURE [J] GENERATION Season 6 #2 「the hibernator」 #6 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 「TRUE Q」 08:30 3 #1 「'CHAOS' Part One」 09:00 09:00 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 09:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 09:30 S.W.A.T. Season 3 09:30 #15 #6 「Crab Mentality」 「KINGDOM」 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:30 10:30 10:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 10:30 DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Season 10:30 #16 2 「Survivor」 #12 11:00 11:00 「The Final Frontier」 11:00 11:30 11:30 11:30 information [J] 11:30 information [J] 11:30 12:00 12:00 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 #13 #19 「A Desperate Man」 「The Good Son」 12:30 12:30 12:30 13:00 13:00 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 #14 #20 「Life Before His Eyes」 「The Missionary Position」 13:30 13:30 13:30 14:00 14:00 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 #15 #21 「Secrets」 「Rekindled」 14:30 14:30 14:30 15:00 15:00 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 #16 #22 「Psych out」 「Playing with Fire」 15:30 15:30 15:30 16:00 16:00 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 #17 #23 「Need to Know」 「Up in Smoke」 16:30 16:30 16:30 17:00 17:00 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 #18 #24 「The Tell」 「Till Death Do Us Part」 17:30 17:30 17:30 18:00 18:00 18:00 MACGYVER Season 2 [J] 18:00 THE MYSTERIES OF LAURA 18:00 #9 Season 1 「CD-ROM + Hoagie Foil」 #19 18:30 18:30 「The Mystery of the Dodgy Draft」 18:30 19:00 19:00 19:00 information [J] 19:00 THE BLACKLIST Season 7 19:00 #14 「TWAMIE ULLULAQ (NO. -

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

Super! Drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15Th

Super! drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese [D]=in Danish 2020.11.30 2020.12.01 2020.12.02 2020.12.03 2020.12.04 2020.12.05 2020.12.06 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 3 06:00 BELOW THE SURFACE 06:00 #20 #21 #22 #23 #1 #8 [D] 「Skyscraper - Power」 「Wind + Water」 「UFO + Area 51」 「MacGyver + MacGyver」 「Improvise」 06:30 06:30 06:30 07:00 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #4 GENERATION Season 7 #7「The Grant Allocation Derivation」 #9 「The Citation Negation」 #11「The Paintball Scattering」 #13「The Confirmation Polarization」 「The Naked Time」 #15 07:30 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 information [J] 07:30 「LOWER DECKS」 07:30 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #8「The Consummation Deviation」 #10「The VCR Illumination」 #12「The Propagation Proposition」 08:00 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 #5 #6 #7 #8 Season 3 GENERATION Season 7 「Thin Lizzie」 「Our Little World」 「Plush」 「Just My Imagination」 #18「AVALANCHE」 #16 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 「THINE OWN SELF」 08:30 -

BEACH HUTS Selling Secrets – Everything You Need to Know About Selling Your Property on the Prom …

T 01273 735237 59 Church Road F 01273 820592 Hove E [email protected] East Sussex BN3 2BD W www.callaways.co.uk Callaways Residential Sales & Lettings BEACH HUTS Selling Secrets – everything you need to know about selling your property on the prom … Heather Hilder-Darling Callaways est a te age nts Beach,, Huts, for a never-to-be- forgotten summer of seaside memories … ,, Award winning Estate & Lettings Agency 2009 – 2017 UK REAL ESTATE R E A L EST A T E in association with ««««« BEST REAL BEST REAL ESTATE ESTATE AGENCY AGENCY EAST SUSSEX UK BEST REAL ESTATE EAST SUSSEX AGENCY EAST SUSSEX Callaways Estate & Lettings Agent Callaways Estate Callaways by Callaways & Lettings Agent Callaways est a te age nts 59 Church Road, Hove BN3 2BD Tel: 01273 735237 B1 Yeoman Gate, Yeoman Way Worthing BN13 3QZ Tel: 01903 831338 [email protected] www.callaways.co.uk Thank you for downloading this guide from Callaways 1. Preparing to sell your Beach Hut Residential Sales & Lettings. 2. Useful documents and information We hope you find it helpful. 3. What to include in the sale If you have any questions or 4. Preparing your Beach Hut for Sale comments or you would like 5. Photography to organise a free saleability 6. Viewings and advice consultation, then 7. Agreeing a sale please click here. 8. Managing the sale to completion 9. Preparing for hand-over 10. Contact us page 2 sales ... lettings ... property management ... new homes August,, – children playing, lapping water, cups of tea and the sea … ,, Preparing to sell your Beach Hut How is the current value of current value, and what we recommend as local market and straight talking a marketing strategy that will help sell your good advice, which clients appreciate. -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

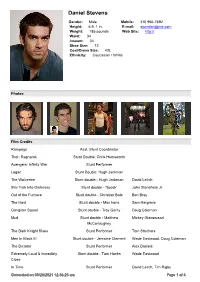

Daniel Stevens

Daniel Stevens Gender: Male Mobile: 310 956-7692 Height: 6 ft. 1 in. E-mail: [email protected] Weight: 185 pounds Web Site: http:// Waist: 34 Inseam: 34 Shoe Size: 12 Coat/Dress Size: 42L Ethnicity: Caucasian / White Photos Film Credits Rampage Asst. Stunt Coordinator Thor: Ragnarok Stunt Double: Chris Hemsworth Avengers: Infinity War Stunt Performer Logan Stunt Double: Hugh Jackman The Wolverine Stunt double - Hugh Jackman David Leitch Star Trek Into Darkness Stunt double - 'Spock' John Stoneham Jr. Out of the Furnace Stunt double - Christian Bale Ben Bray The Host Stunt double - Max Irons Sam Hargrave Gangster Squad Stunt double - Troy Garity Doug Coleman Mud Stunt double - Matthew Mickey Giacomazzi McConaughey The Dark Knight Rises Stunt Performer Tom Struthers Men In Black III Stunt double - Jemaine Clement Wade Eastwood, Doug Coleman The Dictator Stunt Performer Alex Daniels Extremely Loud & Incredibly Stunt double - Tom Hanks Wade Eastwood Close In Time Stunt Performer David Leitch, Tim Rigby Generated on 09/26/2021 12:36:25 am Page 1 of 3 Jack Gill, Daniel Stevens Green Lantern Stunt double - Ryan Reynolds Gary Powell Unstoppable Stunt double - Chris Pine Gary Powell Warrior Stunt Performer J.J. Perry The Expendables Stunt Performer Chad Stahelski X-Men Origins: Wolverine Stunt double - Hugh Jackman J.J. Perry, Chad Stahelski Takers Stunt Performer Lance Gilbert Angel of Death Stunt Performer Ron Yuan Once Fallen Stunt double - Peter Greene Noon Orsatti Iron Man Stunt double - 'Iron Man' Tom Harper, Keith Woulard Midnight Meat Train Stunt double - Vinnie Jones David Leitch Where The Wild Things Are Stunt double - 'Judith' Darrin Prescott Suffering Man's Charity Stunt double - Alan Cumming Nick Plantico Crank Stunt Performer Darrin Prescott Ravenswood Stunt double - Travis Fimmel Richard Boue Superman Returns Stunt Performer R.A. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Production Crew & Talent

VISIT SANTA BARBARA & FILM COMMISSION Office: (805) 966-9222 Fax: (805) 966-1728 www.filmsantabarbara.com Countywide, Online Location Library with 35,000+ Photos PRODUCTION CREW & TALENT ACTORS / MODELS CAMERA OPERATORS & ASSISTANTS HELLO GORGEOUS MODELS Shannon Loar-Coté (Agent & Owner) GREEN, ERIC J. – Director, Producer, Camera Direct: (805) 689-9613 Operator of reality and documentary Email: [email protected] Direct: (310) 699-4416 Website: www.hellogorgeousmodels.com Location: Email: [email protected] Santa Barbara, CA Location: Santa Barbara, CA About: A full service, licensed model and talent Experience: 5+ years as a director/producer on agency in Santa Barbara, California. reality shows such as Couples Therapy with Dr Clients: Samsung, Oprah Winfrey Network, Pier 1 JennH on V -1, Family Therapy on VH-1 and Imports, Hennessy, Kimpton Hotels, Kay Jewelers, Famously Single on E!. 10+ years experience Nationwide Insurance, William Sonoma shooting mostly reality and documentary style. Have shot most seasons of Celebrity Rehab With STEVENS, CINDY – Casting Director Actors Talent Dr. Drew on VH-1, Mobbed on Fox and Food Registry/Kids Casting of Santa Barbara County Paradise on Travel Channel Have shot with most (Owner) ENG style cameras both SD and HD. Direct: (805) 350-0387 Owner of a Canon C100 camera package, LED Email: [email protected] light package and audio gear. About: A full service talent registry for actors with all levels of experience, and production. Connecting MATHIEU, PAUL - Producer / Camera Operator talent with production: film, theater, commercials, Owner of West Beach Films voice over, models, etc. Direct: (805) 448-9261 Email: [email protected] Website: www.westbeachfilms.com BARNETT, LAURELLE - Union Actor/Voiceover Experience: West Beach Filmss i comprised of a Artist/Extra seasoned team of both union and non-union Direct: (805) 801-2717 [email protected] producti on crew, and sources gear and services About: Female, 45-65 range, upscale look, brunette locally whenever available. -

Where I Came from Sara Miller Mccune, Founder of Sage Publishing and Philanthropist, Looks Back

Congregation B’nai B’rith FALL 2017 • JOURNAL VOL. 92 NO. 2 • ADAR 5777 - TISHREI 5778 FOCUS: YEAR OF STORIES Where I Came From Sara Miller McCune, Founder of Sage Publishing and Philanthropist, Looks Back Interview by Rabbi Steve Cohen This summer, Sara Miller McCune and I managed to find some time together, for a relaxed conversa- tion about her Jewish background and how it has shaped her, and her thoughts about Judaism’s wisdom of that type to be had in New York City. He traveled as far as for our generation. Although Sara and I have known Texas but had no luck, and so returned to New York and learned a new trade as a kosher butcher, which he remained all his work- each other for over twenty years, I was surprised and ing life. He was a Kohen and proud of it, and very devoted to his delighted by many of her reminiscences. We are hon- religious observance. ored and grateful to Sara for allowing us to share some My paternal grandfather, Benjamin Miller, was a tailor and came of her story with the rest of the CBB family. to this country with my grandmother Ester Miller, who was Sara, I'd like to begin by asking you a little bit about your five-foot tall and ruled the entire family. With my grandmother’s Jewish upbringing. Could you tell me a little bit about your drive, they bought the brownstone buildings housing the tailor parents and where they came from, and where did you come shop. -

Trustees Take Action on 2 Items Board Authorizes Issuing Bond for Capital Projects, Considers Revising Purchasing Policies

GRIDIRON 2017: The high school football season preview section inside D1-D6 USA TODAY Vehicle rampage in Spain kills 13, wounds 100s C1 FRIDAY, AUGUST 18, 2017 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents Trustees take action on 2 items Board authorizes issuing bond for capital projects, considers revising purchasing policies BY BRUCE MILLS lution is the most-common mecha- be borrowed. That total is basically the The procurement audit was the dis- [email protected] nism for school districts in the state to same amount that the district bor- trict’s first since Sumter School Dis- annually fund capital projects and rowed last year, Griner said. tricts 2 and 17 consolidated in 2011. In addition to clarifying its settle- then pay back the money, according to Also, on Monday the board unani- According to officials, the consolidat- ment agreement with former Superin- Sumter School District Chief Finan- mously approved a motion to consider ed district had a two-year grace period tendent Frank Baker, Sumter School cial Officer Chris Griner. The district recommendations — or suggestions — before a procurement audit was neces- District’s Board of Trustees took ac- is expected to enter a pool with other from its advisory finance committee sary. The procurement audit that was tion on two items after returning from school districts in the state to draw for potential revisions to its procure- completed represented the three-year executive session behind closed doors down the interest rate on the short- ment, or purchasing, policies. The fi- period of 2013-16. The finance commit- Monday at its regular monthly meet- term borrowing. -

399 a ABC Range 269-72 Aboriginal Peoples

© Lonely Planet Publications 399 Index A animals 27-30, see also individual Hazards Beach 244 ABCABBREVIATIONS Range 269-72 animals Injidup Beach 283 AboriginalACT peoplesAustralian Capital Arenge Bluff 325 Jan Juc beach 141 Territory Adnyamathana 267 Aroona Homestead 270 Kilcarnup Beach 286 NSW New South Wales Brataualung 175 Aroona Hut 270 Le Grand Beach 302 NT Northern Territory Daruk 65 Aroona Valley 270 Lion’s Head Beach 131 Qld Queensland Dharawal 58 Arthur’s Seat 133 Little Beach 58 SA South Australia Djab wurrung 150 ATMs 367 Little Marley Beach 59 Tas Tasmania INDEX Gamilaroi 110 Augusta 281 Little Oberon Bay 180 Vic Victoria Jandwardjali 150 Australian Alps Walking Track 157, 157 Marley Beach 59 WA Western Australia Krautungulung 181 Australian Capital Territory 84 Milanesia Beach 146 Malyankapa 123 Needles Beach 131 Pandjikali 123 B Norman Beach 180 Port Davey 236 B&Bs 358 Oberon Bay 180 Wailwan 110 Babinda 356 Osmiridium Beach 241 Western Arrernte 321 backpacks 393 Peaceful Bay 291-2, 296 Acacia Flat 73 Badjala Sandblow 347 Picnic Bay 179 accidents 385-6 Bahnamboola Falls 340 Prion Beach 240, 241 accommodation 357-60 Bald Head 302 Putty Beach 55-8 Acropolis, the 228 Baldry Crossing 133 Quininup Beach 284, 44 Adaminaby 95 Balor Hut 113 Redgate Beach 287 Adelaide 251-3 Banksia Bay 351 Safety Beach 132 Admiration Point 101 Banksia Creek 351 Seal Cove 186 Aeroplane Hill 118 banksias 45 Sealers Cove 178 agriculture 46 Bare Knoll 203-4 Secret Beach 186 air travel 372-5 Barn Bluff 220, 222 Smiths Beach 283 airports 372-3 Barrington -

Mid-Season-Lineup-Release Final

GLOBAL RINGS IN 2017 WITH STELLAR MIDSEASON PRIMETIME LINEUP Network Celebrates the New Year with the Premiere of New Canadian Drama Ransom on January 1 Compelling New Original Drama Mary Kills People Joins Global’s Schedule January 25 Additional New Series The Blacklist: Redemption and Chicago Justice Join New Episodes of Fall’s Breakout Hits and New Seasons of Returning Favourites For additional photography and press kit material visit: http://www.corusent.com To view Global’s midseason and original series Ransom promos: Midseason Promo and Ransom Promo To share this release socially: http://bit.ly/2h6e7Up For Immediate Release TORONTO, December 20, 2016 – Coming off of a highly successful fall season with three of the top five new fall series, Global rings in 2017 with a robust midseason primetime lineup. The network heads into the winter season with a schedule packed with Canada’s most-watched programing including this season’s most-anticipated new and returning series. Kicking off the New Year are two new Canadian original drama series. Inspired by the professional experiences of distinguished crisis negotiator Laurent Combalbert, comes Ransom, a high stakes suspense drama premiering on Sunday, January 1 at 8:30 p.m. ET/8 p.m. PT on Global. Starring Luke Roberts (Wolf Hall, Game of Thrones), as Eric Beaumont, a crisis and hostage negotiator whose team is brought in to save lives when no one else can, the series moves to Wednesdays at 8 p.m. ET/PT starting January 4 and Saturdays at 8 p.m. ET/PT beginning January 7. Then, Global’s compelling, new character-driven drama Mary Kills People joins the schedule Wednesday, January 25 at 9 p.m.