Developing the Concept of a Natural Capital Trust in the West of England and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 2019

Contents / Diary of events FEBRUARY 2019 Bristol Naturalist News Picture © Alex Morss Discover Your Natural World Bristol Naturalists’ Society BULLETIN NO. 577 FEBRUARY 2019 BULLETIN NO. 577 FEBRUARY 2019 Bristol Naturalists’ Society Discover Your Natural World Registered Charity No: 235494 www.bristolnats.org.uk CONTENTS HON. PRESIDENT: Andrew Radford, Professor 3 Diary of Events of Behavioural Ecology, Bristol University Nature in Avon – submissions invited; HON. CHAIRMAN: Ray Barnett [email protected] 4 Society Winter Lecture; HON. PROCEEDINGS RECEIVING EDITOR: Subs. due; Welcome new members Dee Holladay, [email protected] ON EC 5 Society AGM ; Bristol Weather H . S .: Lesley Cox 07786 437 528 [email protected] 6 Natty News: Fossil evidence on evolution HON. MEMBERSHIP SEC: Mrs. Margaret Fay of feathers & colour vision; volcanic doubts; Beech 81 Cumberland Rd., BS1 6UG. 0117 921 4280 disease; migrant murder; Fin whales [email protected] 8 BOTANY SECTION HON. TREASURER: Mary Jane Steer 01454 294371 [email protected] Botanical notes ; Talk Report; Field Mtg Reports; Libby Houston’s BULLETIN COPY DEADLINE: 7th of month before new honour (p10); Plant Records publication to the editor: David B Davies, 51a Dial Hill Rd., Clevedon, BS21 7EW. 12 GEOLOGY SECTION 01275 873167 [email protected] 13 INVERTEBRATE SECTION . Notes for February; Health & Safety on walks: Members Wildlife Photographer 2018 participate at their own risk. They are 14 LIBRARY Books to give away responsible for being properly clothed and shod. Dogs may only be brought on a walk with prior 16 ORNITHOLOGY SECTION agreement of the leader. Meeting Reports; 18 Breeding Bird Survey; Recent News 19 MISCELLANY Botanic Garden Avon Organic Group 20 Gorge & Downs Wildlife Project; Cover picture:: Twenty of the 48 plants found in flower on New Year’s Day. -

NORTH SOMERSET COUNCIL Green Infrastructure Strategy

SUMMARY JANUARY 2021 NORTH SOMERSET COUNCIL Green Infrastructure Strategy Parks Beaches Green spaces Countryside Waterways Wildlife 2 Our parks, beaches, green spaces, wildlife, countryside, public rights of way and waterways are precious, and we have prepared this new strategy to help to protect and enhance them. 3 Green Infrastructure Strategy Contents What is Green Infrastructure? 5 Why do we need a strategy? 6 Aims, vision and objectives 8 Our green infrastructure 10 Green infrastructure opportunities 15 Action Plan 27 The information in this summary document has been drawn from a much wider piece of work that includes the data which underpins the maps shown in this summary; a more detailed analysis of North Somerset’s GI; and wide ranging information about GI in general. It is the detailed report that will underpin the way the Council manages GI across North Somerset. View document > Summary January 2021 4 What is Green Infrastructure? Green infrastructure is a technical term that we use as shorthand to describe how we will look after these spaces. We have adopted this definition below to help explain in more detail what we mean. Green infrastructure is a strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features designed and managed to deliver a wide range of benefits (typically called ecosystem services) such as water purification, air quality, biodiversity, space for recreation and climate This network of green (land) and blue (water) spaces can improve mitigation and adaptation. environmental conditions and therefore citizens’ health and quality of life. It also supports a green economy, creates job opportunities and enhances biodiversity. -

Ecosystems Woodlands Fieldwork

Woodland ecosystems and their management Embedding fieldwork into the curriculum Woodlands fieldwork can add value to a range of topics including: • Tourism and leisure • National Parks • Woodland management • Environmental conservation • Ecosystems • Conflicts of interest • Economic use of woodlands • Comparing types and ages of woodlands • Vegetation species • Microclimates There are several cross curricular themes such as: • Geography units such as unit 16 'What is development?', in terms of resource use • ICT, including using a mapping package, using internet search engines • Citizenship thorough conflicts of interest, considering topical issues, justifying personal opinion • Science in terms of habitats, toxic materials in food chains and environmental chemistry • Geography units such as unit 8 'Coastal environments' and unit 13 'Limestone landscapes of England' in terms of human impacts on natural areas and pressures of tourism • key skills, working with others, improving own learning and performance • PSHE in terms of taking responsibility for own actions • Enquiries and decision making preparation for GCSE and A level QCA unit schemes available to download for: Geography http://www.standards.dfes.gov.uk/schemes2/secondary_geography/?view=get Science: http://www.standards.dfes.gov.uk/schemes2/secondary_science/?view=get Citizenship http://www.standards.dfes.gov.uk/schemes2/citizenship/?view=get Accompanying scheme of work The scheme of work below has been created using aspects from a variety of QCA units and schemes available, including: Unit 14: Can the earth cope? Ecosystems, population and resources http://www.standards.dfes.gov.uk/schemes2/secondary_geography/geo14/?view=get Unit 23: Local action, global effects http://www.standards.dfes.gov.uk/schemes2/secondary_geography/geo23/?view=get Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers © Woodland Ecosystems About the unit The unit is adapted from the QCA scheme of work Unit 14 Can the earth cope? Ecosystems population and resources. -

Download This Document

Mortimer, E.J. (2016) Ecotypic variation in 'Lotus corniculatus L.' and implications for grassland restoration: interaction of ecotypes with soil type and management, in relation to herbivory. PhD thesis. Bath Spa University. ResearchSPAce http://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/ Your access and use of this document is based on your acceptance of the ResearchSPAce Metadata and Data Policies, as well as applicable law:- https://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/policies.html Unless you accept the terms of these Policies in full, you do not have permission to download this document. This cover sheet may not be removed from the document. Please scroll down to view the document. Ecotypic variation in Lotus corniculatus L. and implications for grassland restoration: Interaction of ecotypes with soil type and management, in relation to herbivory Erica Jane Mortimer A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bath Spa University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Society, Enterprise & Environment, Bath Spa University 2016 This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that my thesis is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law or infringe any third party’s copyright or other intellectual property right. Word count: 37515 Ancillary Data: 23116 (Contents/glossary/acknowledgements: 3311; tables/figures/captions: 10438; references: 9367) Appendices: 16417 2 ABSTRACT This research assesses the importance of using ecologically-similar rather than geographically-local seed in grassland restoration projects, with particular reference to herbivorous invertebrates, including pollinators. -

Our Top 20 Reserves Access: Paths Can Be Muddy, Slippery and Steep-Sided

18 Weston Big Wood Grid ref: ST 452 750. Nearest postcode: BS20 8JY Weston Big Wood is one of Avon’s largest ancient woodlands. In springtime, the ground is covered with wood anemones, violets and masses of bluebells. Plants such as herb paris and yellow archangel together with the rare purple gromwell, show that this is an ancient woodland. The wood is very good for birds, including woodpecker, nuthatch, and tawny owl. Bats also roost in the trees and there are badger setts. Directions: From B3124 Clevedon to Portishead road, turn into Valley Road. Park in the lay-by approx 250 metres on right, and walk up the hill. Steps lead into the wood from the road. Our top 20 reserves Access: Paths can be muddy, slippery and steep-sided. Please keep away from the quarry sides. 19 Weston Moor Grid ref: ST 441 741. Nearest postcode: BS20 8PZ This Gordano Valley reserve has open moorland, species-rich rhynes, wet pasture and hay meadows. It is full of many rare plants such as cotton grass, marsh pennywort and lesser butterfly orchid, along with nationally scarce invertebrates such as the hairy dragonfly and ruddy darter. During the spring and summer the fields attract lapwing, redshank and snipe. Other birds such as little owl, linnet, reed bunting and skylark also breed in the area. Sparrowhawk, buzzard and green woodpecker are regularly recorded over the reserve. Directions: Parking is restricted and the approach to the reserve is hampered by traffic on the B3124 being particularly fast-moving. When parking please do not block entrances to farms, fields or homes. -

Bristol Naturalist News

Contents / Diary of events JULY-AUGUST 2019 Bristol Naturalist News Photo © Nick Owens Discover Your Natural World Bristol Naturalists’ Society BULLETIN NO. 582 JULY-AUGUST 2019 BULLETIN NO. 582 JULY-AUGUST 2019 Bristol Naturalists’ Society Discover Your Natural World Registered Charity No: 235494 www.bristolnats.org.uk CONTENTS HON. PRESIDENT: Andrew Radford, Professor 3 DIARY of Events; Nature in Avon; of Behavioural Ecology, Bristol University Welcome new members ON HAIRMAN H . C : Ray Barnett [email protected] 4 SOCIETY ITEMS: Mid-week Walks; HON. PROCEEDINGS RECEIVING EDITOR: Find a Bumblebee in Scotland; Dee Holladay, [email protected] ON EC 5 Bristol Weather H . S .: Lesley Cox 07786 437 528 [email protected] 6 NATTY NEWS : Bees, Feathers, HON. MEMBERSHIP SEC: Mrs. Margaret Fay 81 Cumberland Rd., BS1 6UG. 0117 921 4280 7 Bedbugs; Poisoned Birds; Fracking; Flock mechanics; Re-wilding; [email protected] HON. TREASURER: Mary Jane Steer 8 Duke of Burgundy; Fungus find 01454 294371 [email protected] 9 Westonbirt BioBlitz / BNS Survey BULLETIN COPY DEADLINE: 7th of month before publication to the editor: David B Davies, 10 BOTANY SECTION 51a Dial Hill Rd., Clevedon, BS21 7EW. ‘Other’ meetings; 01275 873167 [email protected] 11 Botanical notes ; Meeting Reports; . 13 Plant Records Health & Safety on walks: Members 15 GEOLOGY SECTION participate at their own risk. They are Book review: Dinosaurs Rediscovered responsible for being properly clothed and shod. Dogs may only be brought on a walk with prior 16 INVERTEBRATE SECTION agreement of the leader. Notes for June; Points of Interest 18 LIBRARY Books to give away; Donations; Steep Holm News 20 ORNITHOLOGY SECTION Sea Bird Safari; Swift nest petition; Meeting Report; Recent News ; 23 MISCELLANY Botanic Garden; 24 Gorge & Downs Wildlife Project; St George’s Flower Bank Fun-day Cover picture: The endangered Great Yellow Bumblebee – we are encouraged to find it in its retreat in the north of Scotland. -

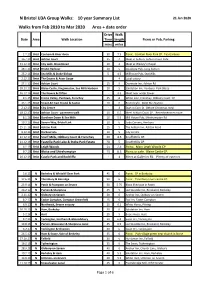

N Bristol U3A Group Walks: 10 Year Summary List

N Bristol U3A Group Walks: 10 year Summary List 21 Jan 2020 Walks from Feb 2010 to Mar 2020 Area + date order Drive Walk Date Area Walk Location Time length Picnic or Pub, Parking mins miles 2.7.10 Brist Conham & River Avon 30 7.5 Picnic. Conham River Park CP. Tea Gardens 16.7.10 Brist Ashton Court 15 4 Meet in Ashton. Ashton Court Cafe 31.12.10 Brist City walk -Broadmead 10 2 Meet at Wesley's Chapel 28.1.11 Brist Bristol Harbour 10 5 Dovecote Pub, Long Ashton 25.2.11 Brist Sea Mills & Stoke Bishop 5 4.5 Millhouse Pub, Sea Mills 2.12.11 Brist The Downs & Avon Gorge - 4 Local eatery 27.1.12 Brist Ashton Court 15 5 Dovecote Inn, Ashton Rd 28.12.12 Brist Blaise Castle, Kingsweston, Sea Mills Harbour 10 5 Salutation Inn, Henbury. Park Blaise 26.12.14 Brist The Downs & Clifton - 3.5 Meet near water tower. 9.1.15 Brist Frome Valley, Purdown, Frenchay 25 8 White Lion, Frenchay. Oldbury Court CP 23.1.15 Brist Street Art East Bristol & Easton 10 6 Bristol Cafe. Meet Bus Station 2.12.15 Brist City Centre - 4 Start in Corn St. Before Christmas meal 18.12.15 Brist Ashton Court - pavement walk 10 6.5 Meet Ashton Court CP. Refreshments en route 8.1.16 Brist Durdham Down & Sea Mills 10 5.5 Mill House Pub, Shirehampton Rd 19.2.16 Brist Severn Way, Bristol Link 20 6 Toby Carvery, Henbury 25.11.16 Brist Ashton Park 15 5 The Ashton Inn, Ashton Road 9.12.16 Brist Harbourside 10 5 City Centre 22.12.17 Brist Snuff Mills, Oldbury Court & Frenchay 20 4.5 Snuff Mills CP. -

Severn Wonders? Severn Estuary

‘Whether you are looking for a leisurely cruise or Severn Estuary Forum competitive racing, the Severn Estuary has it all in a Thursday 8th June 2006 unique picturesque setting.’ Susanne Newbold, Bristol Channel Yachting Association Changing times and tides: the future of the Severn Estuary A conference to discuss issues affecting the future of the What is Severn Wonders? Severn Estuary. ‘I love to walk along Severn Beach; the estuary light Walton Park Hotel, Clevedon Severn Wonders is a three week festival of events to is always changing, and in winter large flocks of Please contact the Severn Estuary Partnership on 029 20 874713 celebrate the Severn Estuary. On the inside of this leaflet birds feed on the mud’ or Email [email protected] to find out more. is a list of the events and a map showing where they are Sandra Blackburn, Severn Beach Resident Booking essential. Conference only £12 Conference and Cruise: £25 taking place. The events range from walks and talks to regattas, open days, boat trips, farmers markets and island visits. ‘Abundant species, all year round, from both boat and shore’ Why is Severn Wonders Don Metcalfe, Bristol Channel Federation of Sea Anglers taking place? The festival encourages everyone around the estuary to Severn Wonders Cruise work together, to help ensure our estuary is well Thursday 8th June 2006 managed for future generations. Severn Wonders is about celebrating the estuary and what it means for Reception with speakers and displays on a different people, groups and organisations. late afternoon cruise. Depart Penarth Pier 1400 and arrive Clevedon Pier 1500 Depart Clevedon Pier 1530 and arrive Penarth Pier 1715 How you can get involved Depart Penarth Pier 1730 and arrive Clevedon Pier 1830 and discover the estuary? All times approximate. -

Flora of Somerset

A SUPPLEMENT TO THE FLORA OF SOMERSET EDWARD SHEARBURN MARSHALL, M.A., F.L.S. RECTOR OF WEST MONKTON. Uaunton : PUBLISHED BY THE SOMERSETSHIRE ARCH^OLOGICAL AND NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY. 1914 ; PREFACE. In these pages I have tried to record the various additions or corrections since the pubHcation of Mr. Murray's book ; which, though dated 1896, was not (I beheve) issued until early in the following year. There is a certain fitness in my continuing his work ; for we were intimate friends from the autumn of 1882 until his death, and I had a small share in his Somerset explorations : he was also my first real helper in the study of critical plants. I have generally followed the London Catalogue names and standard of species, which is somewhat more liberal than that of Fl. Som. ; Mr. Murray was accustomed to deal with larger areas, and his point of view was synthetical, rather than analytical. Researches have been carried on for many years in the north-west ; the results are embodied in Mr. J. W. White's Flora of Bristol, in my opinion quite the best and most thorough book of its kind, which appeared in 1912. He has most generously allowed me to make full use of it and—as the reader cannot fail to see—it has been my mainstay. Our friend Dr. C. E. Moss has written an important plant-associations work on the of the county ; and I wish to thank my numerous correspondents for their cordial help. The time has not yet come for a new edition of the Somerset Flora, ; several districts stiU need much closer investigation, and my own scanty leisure is so much occupied by other matters that I have been un- iv ablo to (lovoto a great deal of it to local excursions. -

Family Explorer Leaflet

particularly information sourced from third parties. third from sourced information particularly cannot guarantee it is free from errors and omissions, omissions, and errors from free is it guarantee cannot information provided in this publication is correct. But we we But correct. is publication this in provided information Every effort has been made to ensure that the the that ensure to made been has effort Every 2 M48 the Blue Skies Rural Visitors Group. Visitors Rural Skies Blue the S 26 25A 24 S 1 Key Designed, produced and distributed by by distributed and produced Designed, 25 M5 23A 23 or your local library local your or 27 21 E<NGFIK M4 22 www.somersetcoast.com A46 28 1520 Family attraction M49 29 M49 16 [email protected] Email: Email: 30 S 17 Tourist information M5 31 29A 18A 01934 641 741 641 01934 Fax: 800 888 01934 Tel: Tel: 19 18 1 North Somerset County Council BS23 1AT BS23 Council County Somerset North 18 M32 National Trust building Weston-super-Mare GFIK@J?<8; S 18A A4 A420 Beach Lawns Beach :8I;@== 19 3 Ecclesiastical building Weston-super-Mare Tourist Information Centre Information Tourist Weston-super-Mare M5 9I@JKFC More copies are available from your local rural attraction, or from; from; or attraction, rural local your from available are copies More :C<M<;FE Train station 18 20 A46 Battery Point A370 A38 Motorway :fe^i\jYlip A4 98K? A37 to seeing you again soon. again you seeing to Ò A39 Major ‘A’ road residents and visitors. -

Nature in Avon Volume 74 the Plants of Urban Footpaths – Richard Bland

Nature in Avon Volume 74 The Plants of Urban Footpaths – Richard Bland Bristol Naturalists' Society Registered Charity No. 235494 www.bristolnats.org.uk Anyone interested in natural history or geology may apply to join. Membership Categories are:- Full Member Household Member Student Member Corresponding Member For details see Membership section of the website. Besides many general indoor and outdoor meetings, other meetings are specifically devoted to geology, plants, birds, mammals and invertebrates. Members may use the Society's large library. Further information is available on the Society's website (www.bristolnats.org.uk). 2 Editorial A naturalist, according to the Oxford dictionary definition, is ‘one who makes a special study of animals or plants’. Geology and the study of fossils doesn’t get a mention however. This issue of Nature in Avon certainly shows us that the definition should be very much wider and gives a fascinating commentary on the activities of naturalists around Bristol. Gill Brown provides a delightful detailed study of otters living in the Land Yeo (I have lived close to the Land Yeo for 20 years and never knew they were there!). Des Bowring has studied his local patch in Montpelier and reports on an amazing array of wildlife on his doorstep. Richard Bland has been walking several local pathways and provides a detailed and sometimes surprising account of the plants he found. Richard Ashley has spent time on the shore at Clevedon and explains how the curious Liesegang Rings are formed. Recording is an important part of what naturalists do and Ray Barnett gives us a full report of the local invertebrate life around Bristol. -

Biodiversity and Trees Planning Document

Biodiversity and trees developments withinNorth Somerset Supplementary planningdocument for Adopted December 2005 This Supplementary Planning Document supplements the polices of the Joint Replacement Structure Plan the Adopted North Somerset Local Plan the Emerging North Somerset Replacement Local Plan Adopted by North Somerset Council December 2005 Acknowledgement for photos Acknowledgement Photos Ian McGuire Water vole Copyright English Nature Greater horseshoe bat, dormouse box and otter Judith Tranter Quarry, Blagdon Lake Andrew Town Bee orchid, willow tree and butterfly Robin E Wild Bluebells Jane Brewer Veteran tree Pauline Homer Development and various habitats Andrew Edwards Land Yeo Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Local policies 5 3 Trees and development 6 4 Protected sites 8 5 Protected species 9 6 Objectives 10 7 Minor developments 11 8 Major developments 12 9 Conclusions 17 Annexes These can be found on the North Somerset Council website: www.n-somerset.gov.uk 1 North Somerset Local Plan policies 2 Joint Replacement Structure Plan policy 3 North Somerset Replacement Local Plan policies 4 Legislation and policy guidance 5 Tree requirements 6 List of Wildlife Sites 7 Protected species guide 8 Householder leaflet 9 Biodiversity checklist for developers 10 When to survey for various species 11 Regional Policies 12 Notable species 13 List of BAP species and habitats 14 Contact list 15 References PLANNING GUIDANCE ON BIODIVERSITY AND TREES 1 1 Introduction Biodiversity is a term that has been used since the Convention on Biological Diversity was signed by 159 governments, including the UK government, at the first Earth Summit in 1992 and refers to the variety of life on earth.