Natural Law Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book Socrates from Antiquity to the Enlightenment 1St Edition

SOCRATES FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE ENLIGHTENMENT 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michael Trapp | 9781351899123 | | | | | Socrates from Antiquity to the Enlightenment 1st edition PDF Book Turin: Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese, Kyoto School Objectivism Postcritique Russian cosmism more Instead, the deist relies solely on personal reason to guide his creed, [73] which was eminently agreeable to many thinkers of the time. Meanwhile, the colonial experience most European states had colonial empires in the 18th century began to expose European society to extremely heterogeneous cultures, leading to the breaking down of "barriers between cultural systems, religious divides, gender differences and geographical areas". Plato was born to one of the wealthiest and politically influential families in Athens in B. Sir Isaac Newton's celebrated Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica was published in Latin and remained inaccessible to readers without education in the classics until Enlightenment writers began to translate and analyze the text in the vernacular. His urbanistic ideas, also being the first large-scale example of earthquake engineering , became collectively known as Pombaline style , and were implemented throughout the kingdom during his stay in office. The democrats proclaimed a general amnesty in the city and thereby prevented politically motivated legal prosecutions aimed at redressing the terrible losses incurred during the reign of the Thirty. August Learn how and when to remove this template message. Origin of the Socratic Problem The Socratic problem first became pronounced in the early 19 th century with the influential work of Friedrich Schleiermacher. Constitution and as popularised by Dugald Stewart , would be the basis of classical liberalism. If classes were to join together under the influence of Enlightenment thinking, they might recognize the all-encompassing oppression and abuses of their monarchs and because of their size might be able to carry out successful revolts. -

List of Notable Freemasons List of Notable Freemasons

List of notable freemasons ---2-222---- • Wyatt Earp , American Lawman. • Hubert Eaton , American chemist, Euclid Lodge, No. 58, Great Falls, Montana . • John David Eaton , President of the Canadian based T. Eaton Company . Assiniboine, No. 114, G.R.M., Winnipeg. • Duke of Edinburgh, see Prince Philip , For Prince Philip • Prince Edward, Duke of Kent , (Prince Edward George Nicholas Paul Patrick), member of the British Royal Family, Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of England , member of various lodges including Grand Master's Lodge No 1 and Royal Alpha Lodge No 16 (both English Constitution). • Prince Edward, Duke of York and Albany (25 March 1739 – 17 September 1767), Younger brother of George III of the United Kingdom. Initiated in the Lodge of Friendship (later known as Royal York Lodge of Friendship) Berlin, Germany on July 27, 1765. • Edward VII , King of Great Britain . • Edward VIII , King of Great Britain . • Gustave Eiffel , Designer and architect of the Eiffel Tower. • Duke Ellington , Musician, Social Lodge No. 1, Washington, D.C., Prince Hall Affiliation • William Ellison-Macartney , British politician, Member of Parliament (1885–1903), Grand Master of Western Australia . • Oliver Ellsworth , Chief Justice of the United States (1796–1800) . • John Elway , Hall of Fame Quarterback for Denver Broncos (1983–1998), South Denver- Lodge No. 93, Denver, Colorado . • John Entwistle , Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Member of the Who . • David Erskine, 11th Earl of Buchan , Scottish socialite, Grand Master of Scotland (1782–1784). • Thomas Erskine, 6th Earl of Kellie , Scottish musician, Grand Master of Scotland (1763–1765. • Sam Ervin , US Senator. • Ben Espy , American politician, served in the Ohio Senate. -

El Garantismo Penal De Un Ilustrado Italiano: Mario Pagano Y La Lección De Beccaria

046-IPPOLITO 3/10/08 12:54 Página 525 EL GARANTISMO PENAL DE UN ILUSTRADO ITALIANO: MARIO PAGANO Y LA LECCIÓN DE BECCARIA Dario Ippolito RESUMEN. La teoría normativa del Derecho penal desarrollada por Francesco Mario Pagano debe situarse dentro de la tradición penal ilustrada que le precede, esto es, en la reflexión de Montesquieu y Beccaria. A partir de la influencia de estos autores, Pagano elabora las líneas generales de un proceso penal moderno cimentado en las garantías fundamentales del inculpa- do. La crítica que Pagano dirige contra el procedimiento inquisitorio, entonces vigente, no se arti- cula sólo en el nivel del déficit de garantías del imputado —sobre el que se centraba la principal crítica de los defensores del modelo acusatorio—, además, el autor desafía a los apologetas de la inquisitio en su propio terreno: el de la interpelación represiva. Más allá de la denuncia que Pagano realiza en contra del método procesal del Reino de Nápoles, su reflexión desemboca en una teoría procesalista de carácter garantista. Los principios sobre los cuales tal teoría se articu- la son: el principio de legalidad del proceso, el principio de la imparcialidad del juez, el principio de la paridad de poderes entre acusación y defensa, el principio de contradicción, y el principio de la oralidad y de la publicidad de todo el procedimiento. De esta forma, Pagano intenta dar forma a un coherente sistema de garantías en el cual encontraban expresión y orden las razones políticas y las principales instancias de la Ilustración penal. Palabras clave: garantías fundamentales del inculpado, proceso inquisitorio, proceso acusatorio, Ilustración penal. -

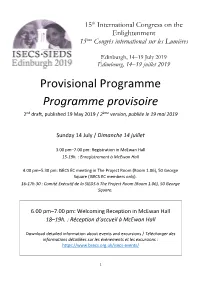

Programme19may.Pdf

15th International Congress on the Enlightenment 15ème Congrès international sur les Lumières Edinburgh, 14–19 July 2019 Édimbourg, 14–19 juillet 2019 Provisional Programme Programme provisoire 2nd draft, published 19 May 2019 / 2ème version, publiée le 19 mai 2019 Sunday 14 July / Dimanche 14 juillet 3.00 pm–7.00 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 15-19h. : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 4.00 pm–5.30 pm: ISECS EC meeting in The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square (ISECS EC members only). 16-17h.30 : Comité Exécutif de la SIEDS à The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square. 6.00 pm–7.00 pm: Welcoming Reception in McEwan Hall 18–19h. : Réception d’accueil à McEwan Hall Download detailed information about events and excursions / Télécharger des informations détaillées sur les événements et les excursions : https://www.bsecs.org.uk/isecs-events/ 1 Monday 15 July / Lundi 15 juillet 8.00 am–6.30 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 8-18h.30 : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 9.00 am: Opening ceremony and Plenary 1 in McEwan Hall 9h. : Cérémonie d’ouverture et 1e Conférence Plénière à McEwan Hall Opening World Plenary / Plénière internationale inaugurale Enlightenment Identities: Definitions and Debates Les identités des Lumières: définitions et débats Chair/Président : Penelope J. Corfield (Royal Holloway, University of London and ISECS) Tatiana V. Artemyeva (Herzen State University, Russia) Sébastien Charles (Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Canada) Deidre Coleman (University of Melbourne, Australia) Sutapa Dutta (Gargi College, University of Delhi, India) Toshio Kusamitsu (University of Tokyo, Japan) 10.30 am: Coffee break in McEwan Hall 10h.30 : Pause-café à McEwan Hall 11.00 am, Monday 15 July: Session 1 (90 minutes) 11h. -

01 Pagano.Pdf

ISTITUTO ITALIANO PER GLI STUDI FILOSOFICI POLITICA E GIURISDIZIONE NEL PENSIERO DI FRANCESCO MARIO PAGANO CON UNA SCELTA DI SUOI SCRITTI PAOLO DE ANGELIS POLITICA E GIURISDIZIONE NEL PENSIERO DI FRANCESCO MARIO PAGANO CON UNA SCELTA DI SUOI SCRITTI Prefazione di GIOVANNI PUGLIESE CARRATELLI ISTITUTO ITALIANO PER GLI STUDI FILOSOFICI © 2006 Istituto Italiano per gli Studi Filosofici Palazzo Serra di Cassano Napoli - Via Monte di Dio, 14 V a Nelli POLITICA E GIURISDIZIONE NEL PENSIERO DI F.M. PAGANO VII PREFAZIONE Dei ‘giacobini’ fondatori della Repubblica Napoletana del 1799 il nome che viene primo alla mente è quello di Francesco Ma- rio Pagano, studiosissimo di Vico, discepolo di Antonio Genovesi, amico di Gaetano Filangieri. Per la sua autorità di giurista, univer- salmente riconosciuta, i suoi compagni gli affidarono il cómpito di redigere un progetto di costituzione per la nascente Repubblica. Al- tamente elogiato da Vincenzo Cuoco fin dalla prima stesura (1801) del Saggio storico sulla rivoluzione di Napoli («I suoi saggi politici sono la miglior cosa che si possa leggere dopo le opere di Vico»), nei Frammenti di lettere a Vincenzio Russo aggiunti al Saggio ricom- pare come principale destinatario delle critiche che il Cuoco move- va alla visione politica dei giacobini napoletani, la cui rivoluzione egli definì ‘passiva’ perché ispirata, a suo avviso, dall’ideologia ri- voluzionaria francese. Si legge infatti nel prologo al Progetto di co- stituzione che «ha esso adottato la Costituzione della Madre Re- pubblica Francese»; ma, ovviamente, «con alcune modificazioni» per «la diversità del carattere morale, le politiche circostanze, e ben anche la fisica situazione delle nazioni». -

Download PDF Van Tekst

De Achttiende Eeuw. Jaargang 43 bron De Achttiende Eeuw. Jaargang 43. Z.n. [Uitgeverij Verloren], Hilversum 2011 Zie voor verantwoording: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_doc003201101_01/colofon.php Let op: werken die korter dan 140 jaar geleden verschenen zijn, kunnen auteursrechtelijk beschermd zijn. i.s.m. 3 [2011/1] Enlightenment? Ideas, transfers, circles, attitudes, practices Christophe Madelein The papers in this issue of De Achttiende Eeuw were presented at a conference organized in Ghent on 22 and 23 January 2010 by the Werkgroep Achttiende Eeuw and called Enlightenment? Ideas, transfers, circles, attitudes, practices. Its starting point was the persistent political and public interest in the classic question ‘What is Enlightenment?’ It is a question that has riddled scholars from the late Enlightenment itself to the late twentieth century, and, indeed, our own day. Kant famously defined Enlightenment as mankind's emergence from self-imposed Unmündigkeit1, while his contemporary Moses Mendelssohn - in a very similar vein - stressed the search for knowledge as a defining characteristic.2 Closer to our own times Michel Foucault suggested - again, not all that differently from Kant's and Mendelssohn's interpretations - that we may envisage modernity, which he sees as the attempt to answer the famous question, as an attitude rather than as a period of history.3 Modernity, in this sense, is accompanied by a feeling of novelty and, more importantly, Enlightenment entails a permanent critique of our historical era. This critical attitude is expressed in a series of practices that are analysed along three axes: the axis of knowledge, the axis of power, the axis of ethics. -

El Garantismo Penal De Un Ilustrado Italiano: Mario Pagano Y La Lección De Beccaria

046-IPPOLITO 3/10/08 12:54 Página 525 EL GARANTISMO PENAL DE UN ILUSTRADO ITALIANO: MARIO PAGANO Y LA LECCIÓN DE BECCARIA Dario Ippolito RESUMEN. La teoría normativa del Derecho penal desarrollada por Francesco Mario Pagano debe situarse dentro de la tradición penal ilustrada que le precede, esto es, en la reflexión de Montesquieu y Beccaria. A partir de la influencia de estos autores, Pagano elabora las líneas generales de un proceso penal moderno cimentado en las garantías fundamentales del inculpa- do. La crítica que Pagano dirige contra el procedimiento inquisitorio, entonces vigente, no se arti- cula sólo en el nivel del déficit de garantías del imputado —sobre el que se centraba la principal crítica de los defensores del modelo acusatorio—, además, el autor desafía a los apologetas de la inquisitio en su propio terreno: el de la interpelación represiva. Más allá de la denuncia que Pagano realiza en contra del método procesal del Reino de Nápoles, su reflexión desemboca en una teoría procesalista de carácter garantista. Los principios sobre los cuales tal teoría se articu- la son: el principio de legalidad del proceso, el principio de la imparcialidad del juez, el principio de la paridad de poderes entre acusación y defensa, el principio de contradicción, y el principio de la oralidad y de la publicidad de todo el procedimiento. De esta forma, Pagano intenta dar forma a un coherente sistema de garantías en el cual encontraban expresión y orden las razones políticas y las principales instancias de la Ilustración penal. Palabras clave: garantías fundamentales del inculpado, proceso inquisitorio, proceso acusatorio, Ilustración penal. -

Politische Philosophie Und Ökonomie in Süditalien

Siebtes Kapitel Politische Philosophie und Ökonomie in Süditalien Einleitung Wolfgang Rother Zu den Vordenkern der süditalienischen Aufklärung zählen Paolo Mattia Doria, Pietro Giannone und Giambattista Vico.Die Hauptthemen ihrer philosophischen Reflexionwaren Staat, Gesellschaft und Geschichte.Ins Visier ihrer Kritik gerieten dabei die durch die weltliche Macht der Kirche gekennzeichneten spätfeudalisti- schen politischen und gesellschaftlichen Verhältnisse.Geschichtsphilosophische Analyse führte zu einer Entmythologisierung politischer Herrschaft und führte zu der Erkenntnis,dass sich Staat und Gesellschaft nicht nur nach eigenen Regeln veränderten, sondern auch durch menschliches Handeln verändert werden konn- ten. So rückte in der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts der Begriff der Reform ins Zentrum des politisch-sozialen Denkens; er avancierte gar zum Leitbegriff der Philosophie: «una filosofia delle riforme per le riforme» (Galasso 1989 [*15: 41]). Politische und gesellschaftliche Reformen, das erkannten die süditalienischen Aufklärer rasch angesichts der Rückständigkeit der Region, insbesondere der unter den spätfeudalistischen Strukturen leidenden Landwirtschaft,hatten immer auch eine ökonomische Dimension. Diese Erkenntnis führte im süditalienischen Denken um die Mitte des 18. Jahrhunderts zu einer Hinwendung zur Ökonomie (vgl. Proto 2003 [*42: 5-10]). Dieser Paradigmenwechsel fand seinen institutio- nellen Niederschlag in der Einrichtung eines ökonomischen Lehrstuhles an der Universität Neapel – gestiftet im Jahr 1753 durch -

Natural Law and the Chair of Ethics in the University of Naples, 1703–1769

Modern Intellectual History (2020), 1–27 doi:10.1017/S1479244320000360 ARTICLE Natural Law and the Chair of Ethics in the University of Naples, 1703–1769 Felix Waldmann* Christ’s College, Cambridge *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This articles focuses on a significant change to the curriculum in “ethics” (moral philosophy) in the University of Naples, superintended by Celestino Galiani, the rector of the university (1732–53), and Antonio Genovesi, Galiani’s protégé and the university’s professor of ethics (1746–54). The art- icle contends that Galiani’sandGenovesi’s sympathies lay with the form of “modern natural law” pioneered by Hugo Grotius and his followers in Northern Europe. The transformation of curricular ethics in Protestant contexts had stemmed from an anxiety about its relevance in the face of moral skepticism. The article shows how this anxiety affected a Catholic context, and it responds to John Robertson’scontentionthatGiambattistaVico’suseof“sacred history” in his Scienza nuova (1725, revised 1730, 1744) typified a search among Catholics for an alternative to “scholastic natural law,” when the latter was found insufficiently to explain the sources of human sociability. In August 1746, Antonio Genovesi was appointed to a professorship of moral phil- osophy or “ethics” in the University of Naples. The appointment marked a second attempt by Celestino Galiani, the university’s rector or cappellano maggiore,tosecure Genovesi a permanent chair (cattedra), after his failed attempt to install Genovesi in the cattedra of logic and metaphysics in March 1744.1 Until Genovesi’s appointment in May 1754 to a professorship of commerce, he would hold the cattedra di etica only in anticipation of a contest or concorso, in which any aspirant could vie for the post. -

Radical, Sceptical and Liberal Enlightenment

Journal of the Philosophy of History 14 (2020) 257–283 brill.com/jph Radical, Sceptical and Liberal Enlightenment James Alexander Assistant Professor, Faculty of Economics, Administrative, and Social Sciences, Dept. of Political Science, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey [email protected] Abstract We still ask the question ‘What is Enlightenment?’ Every generation seems to offer new and contradictory answers to the question. In the last thirty or so years, the most interesting characterisations of Enlightenment have been by historians. They have told us that there is one Enlightenment, that there are two Enlightenments, that there are many Enlightenments. This has thrown up a second question, ‘How Many Enlightenments?’ In the spirit of collaboration and criticism, I answer both questions by arguing in this article that there are in fact three Enlightenments: Radical, Sceptical and Liberal. These are abstracted from the rival theories of Enlightenment found in the writings of the historians Jonathan Israel, John Robertson and J.G.A. Pocock. Each form of Enlightenment is political; each involves an attitude to history; each takes a view of religion. They are arranged in a sequence of increasing sensitivity to history, as it is this which makes it possible to relate them to each other and indeed propose a composite definition of Enlightenment. The argument should be of interest to anyone concerned with ‘the Enlightenment’ as a historical phenomenon or with ‘Enlightenment’ as a philosophical abstraction. Keywords Radical Enlightenment – Sceptical Enlightenment – Liberal Enlightenment – Jonathan Israel – John Robertson – J.G.A. Pocock 1 Introduction Let me begin with a general claim. There are three ways one can write the history of ideas. -

FEDERICO II” Facoltà Di Giurisprudenza

UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI “FEDERICO II” Facoltà di Giurisprudenza TESI DI LAUREA IN CRIMINOLOGIA STORIA DEL CARCERE CON RIGUARDO ALLA REALTA’ DEL XVIII SECOLO Relatore: Candidata: Chiar.mo Prof. TERESA BRUNO FRANCESCO SCLAFANI Matricola 031/19897 Anno Accademico 1999 - 2000 1 INTRODUZIONE Oggetto della presente trattazione è una panoramica sull’evoluzione dei sistemi penitenziari, con particolare riguardo alla realtà del XVIII secolo. L’excursus prende le mosse dall’analisi della realtà carceraria dalle origini al periodo immediatamente antecedente l’Illuminismo. Il XVIII secolo ha rappresentato un punto cruciale nella storia del carcere, diventato nel frattempo penitenziario. Su questa svolta epocale, e in particolare sul ruolo svolto da illustri pensatori quali Cesare Beccaria, Gaetano Filangieri, Antonio Genovesi e i fratelli Verri in Italia, Rousseau e Montesquieu oltralpe, ci si è soffermati nella parte successiva: l’esecuzione della pena, e di conseguenza le condizioni di vita penitenziaria vengono riviste sulla scorta delle nuove idee illuministiche, non tralasciando il ruolo inconsapevolmente prodromico svolto da una parte progressista della Chiesa cattolica. Di particolare interesse si è rivelato l’originale modello, esclusivamente teorico, e il cui prototipo si può ritrovare nel correzionale di San Michele, costruito da Jeremy Bentham, e minuziosamente descritto da Foucault, ma in realtà mai applicato in concreto, se si esclude qualche richiamo architettonico, tra l’altro non suffragato da prove documentali, nell’ “Ergatolo” di Santo Stefano di Ventotene. I penitenziari italiani, in realtà, costituiscono un modello paradigmatico, cui attingeranno i sistemi stranieri. Howard, sotto questo aspetto, visitando le carceri di Porta Portese e Via Giulia a Roma, le prenderà come esempio da esportare, e dal quale prenderanno spunto i famosissimi sistemi auburniano e filadelfiano. -

Annales Benjamin Constant, N° 35 N° 36 Et N° 37

Annales Benjamin Constant, n° 35 n° 36 et n° 37 INDEX DES NOMS RÉELS ET FICTIFS Cet index contient l’ensemble des personnes réelles et fictives (entrées en italique) mentionnées dans le texte et les notes des Annales Benjamin Constant, à l’exclusion de ceux présents dans les titres, sous-titres, schémas, tableaux et arbres généalogiques. Nous avons également écarté l’entrée « Benjamin Constant » elle-même à cause du très grand nombre d’occurrences au sein des contributions. ABAMONTE, Giuseppe : XXXVII, 90 AMARILLA Y HUERTOS, José de : XXXV, 20, ABBT, Thomas : XXXVI, 120 32-33n, 37-38n ACHARD, famille : XXXVI, 245n AMAT, Félix, XXXV, 21 ACHARD, Lucie : XXXVI, 147n, 245 Amélie (Constant) : XXXVI, 274 ACTON, John Francis : XXXVII, 87, 109, 111- AMIEL, Henri-Frédéric : XXXV, 121, 123- 112 124 ; XXXVII, 184 ADAM, Alexander : XXXVII, 45 AMPÈRE, Jean-Jacques : XXXVI, 113n ADAMS, John : XXXV, 87-88n ANCELAIN, avoué : XXXVI, ADDANTE, Luca : XXXVI, 51n ANDERSON, Donovan : XXXVII, 177 Adolphe (Constant) : XXXV, 110, 127 ; ANELLI, Boris : XXXVI, 34, 55n XXXVI, 166, 191, 196 ; XXXVII, 20, 23-34, ANGLÈS, Jules-Jean-Baptiste, comte, Ministre 70-71, 203, 204 d’Etat, préfet de police : XXXV, 165 AGUADO, Olympe : XXXVII, 142 ANGLET, Andreas : XXXVII, 176 AGUESSEAU, Henri François, chancelier d’ : ANGOULÊME, duchesse d’ : voir Marie- XXXVI, 217 Thérèse-Charlotte de France : 200 AGUET, Jean-Pierre : XXXVI, 84n ANNE, reine d’Angleterre : XXXVI, 234 AIGNAN, Etienne : XXXVII, 39 ANTOINE DE BOURBON, roi de Navarre : AJAM, Maurice : XXXVI, 179-180 XXXVI, 240