The Great Reimagining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derry - Londonderry

E A L L M D V E A R L R E O A D LE VA Derry - Londonderry ELM OAD AGARDR BALLN ARK P L L D I A H RO N L R IL O H H H Golf Centre T G A ER B Ballyarnett S E Lake S K R R D A C A P A 13 LDER O R D D OAD A R R O TT A R O R G I A E G O N A F H L R A A K L N G I LA Ballyarnett Y K A B V L I LL L G A R B T B A L D A T Wood B R A A I L O D LY E G R O A N G R E R V R E E O E AD W M P D ERAGH H RO A A U B ILL O H RO P L G R D A E IEL P Skeoge K F R L ING E E PR R B S G Industrial A A D L ARK RN L Park KBRIDGE P O IA OA H Thornhill G T H L College R E O N AD A M Ballyarnett O R Country Park F E I R R R O O A A D D A D O K R R E A S P R K U N O A C E B D D N RAC A A M O S AN R SE FI E E L L SANDA D A L EP G A R D OV R K E R N FE L EN E AM K O 13 RE R PA L K R P A A P P E R S E W L D FI O Y A L P K IE L R M R F L T E A P L E H D H T P 12 L S A D A RE E N V O A N O H R E O O E E S O R LA M C O 1 Galliagh W D G H N ’ H R O A L R DO F G St Therese E O N P A R Galliagh O O D AR I E Linear E R N C I K L L D Football A O L E Primary School N O D A A Nursery School R A R D Park E O W A G N G M GroundS LA D K H O P D H O R E T L TE L E R E K A C R E R G A N E LS C O E W E C T R E K A A R O RTLO R O H W O W OP B IN L P NR P A RE L A D OA E R S E D O E E K S N G L A A M A P L A O D E P L N K R L ND U E E R O O MO V K L AP M M C A O DRU S G R EN H RK 11,11A I L C A A LK P I U S A F D T L P L W L B A HI PE E O R H R H K C AIRVIEW ROAD L A OO F O G H 13 R O R R O A R B N G EA EY W G K A R O W R B R L D U A U L R O L A IS C L I C C L L O L O WO A E O I ODB O A -

BLIND-LIGHT-Sean-Kelly-Gallery

Sean Kelly Gallery 528 West 29 Street 212 239 1181 New York, NY 10001 www.skny.com ANTONY GORMLEY Blind Light October 26 – December 1, 2007 Sean Kelly is delighted to announce a major exhibition of new work by Antony Gormley. The opening of the exhibition will take place on Thursday, October 25th from 6pm until 8pm. The artist will be present. The centerpiece of Gormley’s ambitious exhibition is a room-sized installation that occupies the main gallery entitled Blind Light . Blind Light is a luminous glass room filled with a dense cloud of mist. Upon entering the room-within-a-room, the visitor is disoriented by the visceral experience of the fully saturated air, in which visibility is limited to less than two feet. The very nature of one’s sense of one’s own body and its relationship in space to others is challenged. In Gormley’s words: Architecture is supposed to be the location of security and certainty about where you are. It is supposed to protect you from the weather, from darkness, from un - certainty. Blind Light undermines all of that. You enter this interior space that is the equivalent of being on top of a mountain, or at the bottom of the sea. It is very important for me that inside it you find the outside. Also you become the immersed figure in an endless ground, literally the subject of the work. Blind Light was included this summer in Gormley’s hugely acclaimed exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, London, to unprecedented public and critical approbation. -

John Lafferty (1894 — 1958)

IN ASSOCIATION WITH Design: asgandpartners.com Design: Funders: Partners: With thanks to: Shaun Austin Linen Hall Library Adrian Beattie Bob Mairs Seamus Breslin Catherine Morris Gabrielle Deans Eamonn MacDermott Eileen Diver Sinead McCoole Bríd Ní Dhochartaigh Fearghal McGarry Con Doherty Mary McGuigan Richard Doherty Hugh O’Boyle John Dooher Emmet O’Connor Adrian Grant Public Record Office of Northern Ireland Guildhall Press South Dublin County Libraries Brian Lacey St Columb’s Cathedral Libraries NI Trevor Temple Introduction Welcome to the Tower Museum’s Remembering 1916 programme 2016 is a pivotal year in the Decade of Centenaries as it sees the anniversary of two key events in our shared history, the Easter Rising and the Battle of the Somme. Both of these events have been remembered in a range of different ways and by particular sections of our communities over the last 100 years. These anniversaries present challenges as well as great opportunities. Looking back at the past together allows us to reflect on our shared history in a more holistic way. This proposed programme recognises that much can be learnt when we visit the past together and explore how these events have shaped our cultural heritage and identity. This programme includes the detailed content created for our 1916: Untold Stories exhibition and a list of events which will take place over the coming months to explore a range of themes that relate to the year 1916. Our wider programme also includes a dedicated schools programme aimed at giving students the opportunity to look back at the key events using the 1916: Untold Stories exhibition. -

Guide to Liverpool Waterfront

Guide to Liverpool Waterfront “Three Graces” – Together the Royal Liver Building, Cunard Building and the Port of Liverpool Building make up the Mersey’s ‘Three Graces’ and are at the architectural centre of Liverpool’s iconic waterfront. A massive engineering project has recently extended the canal in front of these three buildings, adding beautifully landscaped seating areas and viewpoints along the canal and the river. Museum of Liverpool – this brand new museum, opened in 2011 is a magnificent addition to Liverpool’s waterfront. Celebrating the origins and heritage of the city, it features collections from National Museums Liverpool that have never been seen before. Otterspool Promenade – The construction of Otterspool Promenade (1950) provided both a new amenity for Liverpool and an open space dividend from the disposal of Mersey Tunnel spoil and household waste; a project repeated three decades later to reclaim the future International Garden Festival site. A favourite with kite fliers this often overlooked wide open space is perfect for views of the river and picnics Antony Gormley’s “Another Place” - These spectacular sculptures by Antony Gormley are on Crosby beach, about 10 minutes out of Liverpool. Another Place consists of 100 cast-iron, life-size figures spread out along three kilometres of the foreshore, stretching almost one kilometre out to sea. The Another Place figures - each one weighing 650 kilos - are made from casts of the artist's own body standing on the beach, all of them looking out to sea, staring at the horizon in silent expectation. Mersey Ferry - There's no better way to experience Liverpool and Merseyside than from the deck of the world famous Mersey Ferry listening to the commentary. -

Press Release Antony Gormley

Press Release New Exhibition meticulously constructed form in which mass and space create an implicit order. Rather than representing the Antony Gormley: body, or being concerned with appearance, this sculpture will become, like CO-ORDINATE IV, an instrument for SUBJECT projection, empathy and mindfulness. In the adjacent gallery will be EDGE III (2012), a solid 22 MAY 2018–27 AUGUST 2018 iron body that stands on the wall at the height of a bed. Its unusual placement, spinning the orientation of the This summer Kettle’s Yard will present ‘SUBJECT’ by space by 90 degrees, acting as a lever on the space Antony Gormley, the first solo artist exhibition to be prompting a sense of disequilibrium and suggesting that staged in Kettle’s Yard’s new galleries. Gormley’s the stability of the world and therefore our orientation site-specific installation will ambitiously push and test within it is relative. the boundaries of these spaces. The exhibition will include both new work and works not previously In the Clore Learning Studio will hang SLIP I (2007) a exhibited in the UK. work that maps a falling body in space using fine steel bars that follow a system of meridians familiar to us Taking as its basis the ‘coordinate’ as a means of from a geographer’s globe. This accurate mapping of the measurement of space and of the body as space, diving body is held within an expanded space frame ‘SUBJECT’ is conceived as a site-specific installation that derived from that same body. The inner body frame has will occupy the whole site, including both galleries, the fallen inside the outer. -

Antony Gormley: Some of the Facts

Antony Gormley: Some of the Facts Tate St Ives 16 June – 2 September 2001 Notes for Teachers As part of the ongoing development of resources for teachers we would like to encourage you to comment on how useful you have found this information and make any suggestions/additions to be incorporated during the exhibition and shared with other educationalists. E-mail [email protected] Call 01736 791114 Art is the means by which we communicate what it feels like to be alive…. Making beautiful things for everyday use is a wonderful thing to do – making life flow more easily – but art confronts life, allowing it to stop and perhaps change direction – they are completely different. Antony Gormley Things already exist. Sculpture already exists. The job is to transform what exists in the outer world By uniting it with the world of sensation, imagination and faith. Action can be confused with life. Much of human life is hidden. Sculpture, in stillness, can transmit what may not be seen. My work is to make bodies into vessels that both contain and occupy space. Space exists outside the door and inside the head. My work is to make a human space in space. Each work is a place between form and formlessness, a time between origin and becoming. A house is the form of vulnerability, darkness is revealed by light. My work is to make a place, free from knowledge, free from history, free from nationality to be experience freely. In art there is no progress, only art. Art is always for the future. -

Crossing Derry Crossing Water Always Furthered Something

Simpson.qxd 17/10/2013 09:41 Page 63 63 Crossing Derry Crossing water always furthered something When quoting this line by Seamus Heaney, Martin McGuinness, Northern Ireland’s deputy first minister, registered several points. He was speaking in Derry at a party for volunteers in Fleadh 2013, the all Ireland music festival which was held Tony Simpson ‘north of the border’ for the first time and had attracted some 400,000 visitors to the city during five days in August. Heaney had died a few days after the Fleadh (pronounced ‘fla’), on 30 August. His loss is keenly felt in Derry, where he attended St Columb’s College as a boarder during his early teenage years. There his passion for poetry and flair for Latin and the classics were nurtured. From a small farm in Mossbawn in south County Derry, he had won a scholarship to St Columb’s, courtesy of the 1947 Education in Northern Ireland Act, passed by the Labour Government of the day, as Heaney himself once remarked. Mr McGuinness was acknowledging Seamus Heaney’s profound contribution to civilization and culture, while also addressing Derry’s divisions and how they are being overcome, literally, by the construction of the new Peace Bridge across the River Foyle. He was speaking a few days after visiting Warrington in the north of England, where he had given the peace lecture which we publish in this issue of The Spokesman. Two boys, twelve- years-old Tim Parry and three-years-old Johnathan Ball, had been killed in an IRA bombing in the town in 1993. -

Volume I Return to an Address of the Honourable the House of Commons Dated 15 June 2010 for The

Report of the Return to an Address of the Honourable the House of Commons dated 15 June 2010 for the Report of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry The Rt Hon The Lord Saville of Newdigate (Chairman) Bloody Sunday Inquiry – Volume I Bloody Sunday Inquiry – Volume The Hon William Hoyt OC The Hon John Toohey AC Volume I Outline Table of Contents General Introduction Glossary Principal Conclusions and Overall Assessment Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online The Background to Bloody www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail Sunday TSO PO Box 29, Norwich NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Order through the Parliamentary Hotline Lo-Call: 0845 7 023474 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone: 0870 240 3701 The Parliamentary Bookshop 12 Bridge Street, Parliament Square, London SW1A 2JX This volume is accompanied by a DVD containing the full Telephone orders/General enquiries: 020 7219 3890 Fax orders: 020 7219 3866 text of the report Email: [email protected] Internet: www.bookshop.parliament.uk TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from £572.00 TSO Ireland 10 volumes 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD not sold Telephone: 028 9023 8451 Fax: 028 9023 5401 HC29-I separately Return to an Address of the Honourable the House of Commons dated 15 June 2010 for the Report of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry The Rt Hon The Lord Saville of Newdigate (Chairman) The Hon William Hoyt OC The Hon John Toohey AC Ordered by the House of Commons -

Fashioning a City of Culture: ‘Life and Place Changing’ Or ’12 Month Party’?

Fashioning a city of culture: ‘life and place changing’ or ’12 month party’? Boland, P., Murtagh, B., & Shirlow, P. (2019). Fashioning a city of culture: ‘life and place changing’ or ’12 month party’? International Journal of Cultural Policy, 25(2), 246-265. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2016.1231181 Published in: International Journal of Cultural Policy Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2016 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in International Journal of Cultural Policy on 09/09/2016, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/10286632.2016.1231181. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:24. Sep. 2021 FASHIONING A CITY OF CULTURE: ‘LIFE AND PLACE CHANGING’ OR ’12 MONTH PARTY’? 1. Introduction In 2004 Iowa’s Director of Cultural Affairs proclaimed “culture is no longer a frill. -

Rifles Regimental Road

THE RIFLES CHRONOLOGY 1685-2012 20140117_Rifles_Chronology_1685-2012_Edn2.Docx Copyright 2014 The Rifles Trustees http://riflesmuseum.co.uk/ No reproduction without permission - 2 - CONTENTS 5 Foreword 7 Design 9 The Rifles Representative Battle Honours 13 1685-1756: The Raising of the first Regiments in 1685 to the Reorganisation of the Army 1751-1756 21 1757-1791: The Seven Years War, the American War of Independence and the Affiliation of Regiments to Counties in 1782 31 1792-1815: The French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812 51 1816-1881: Imperial Expansion, the First Afghan War, the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny, the Formation of the Volunteer Force and Childers’ Reforms of 1881 81 1882-1913: Imperial Consolidation, the Second Boer War and Haldane’s Reforms 1906-1912 93 1914-1918: The First World War 129 1919-1938: The Inter-War Years and Mechanisation 133 1939-1945: The Second World War 153 1946-1988: The End of Empire and the Cold War 165 1989-2007: Post Cold War Conflict 171 2007 to Date: The Rifles First Years Annex A: The Rifles Family Tree Annex B: The Timeline Map 20140117_Rifles_Chronology_1685-2012_Edn2.Docx Copyright 2014 The Rifles Trustees http://riflesmuseum.co.uk/ No reproduction without permission - 3 - 20140117_Rifles_Chronology_1685-2012_Edn2.Docx Copyright 2014 The Rifles Trustees http://riflesmuseum.co.uk/ No reproduction without permission - 4 - FOREWORD by The Colonel Commandant Lieutenant General Sir Nick Carter KCB CBE DSO The formation of The Rifles in 2007 brought together the histories of the thirty-five antecedent regiments, the four forming regiments, with those of our territorials. -

Halloween Prog FINAL.Pdf

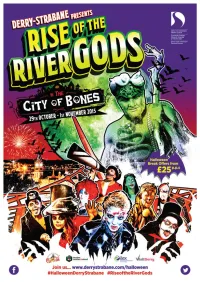

Welcome... , , , fáilte fair faa ye Witamy bienvenue , , Willkommen benvenuto bienvenido Welcome to the world famous Banks of the Foyle Hallowe’en Carnival event guide! With a bigger and even busier programme of events than ever before, coupled with the addition of the rise of the ghostly River Gods from the Foyle and further afield, it’s set to be a week awash with devilish activities for all to experience. The big treat of course is the annual, world renowned, street carnival parade – the biggest in Europe, culminating in the explosive fireworks finale! Be part of the experience! Engage your creative side and show off a crazy costume and join us for the scariest night of the year! Thank you to the following organisations for their support in delivering this programme. 2 Image courtesy of Triggerman Image courtesy As Samhain stirs this City of Bones Smyth’s chisel rises and falls on stone Above Bishop’s Gate, Foyle looks up and Boyne looks down Upon this ghostly riverside town Spirits have stirred them, these riverine heads of rock To summon Liffey and Shannon from the Custom House As the Rivers of Ireland send out the cry, Rise up Lagan, awake Lee and Bann Indus and Clyde shake off your murky bed, to Derry we go to dance with the dead All Hail the Rise of the River Gods... 3 contents... hallowe’en in derry~Londonderry...................... 5 -31 hallowe’en in strabane & surrounding areas... 32 -36 Other events...........................................................36 -38 accommodation offers..........................................40 parking & event information................................42 at a Glance Guide -derry-londonderry............ -

Download Brochure

OFFERS Building 17, Ebrington, Derry / Londonderry, BT47 6FA INVITED Unique Commercial Opportunity suitable for a wide range of uses (subject to full planning) Building 17, Ebrington, Derry / Londonderry, BT47 6FA 028 9050 1501 Features • Former ‘Barrack Masters House’ • Imposing 3 storey, former dwelling of c. 4,040 sq.ft. • Private walled garden of c. 5,850 sq.ft • Suitable for a wide range of commercial uses, subject to obtaining Full Planning Permission • Situated within Ebrington an award winning heritage regeneration scheme • Within walking distance of Waterside & Cityside • Unparalleled views of the River Foyle, Peace Bridge, Cityside and Ebrington Square Locati on Derry / Londonderry is the regional capital of the North West with a population of circa 151,000. Foyleside Shopping Centre 0.6 miles City of Derry Airport 7 miles The City is major tourist destination and in 2018 experienced Letterkenny 21 miles circa 335,000 overnight stays and visitor spend of £55 million in Belfast International Airport 60 miles 2018. Belfast 70 miles Ebrington adjoins the City Centre via the iconic Peace Bridge which benefits from over 1 million crossings per year. 2 www.lisney.com Building 17, Ebrington, Derry / Londonderry, BT47 6FA 028 9050 1501 Description Objective The subject asset comprises an impressive three storey, Georgian We are offering Building 17 to the market in order to attract a property situated along the banks of the River Foyle. The property is new occupier, private sector investment and new, sustainable jobs to Ebrington. situated along the western boundary of the Ebrington site and located at the southern end of Ebrington Square.