3 | 2018 Volume 9 (2018) Issue 3 ISSN 2190-3387

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 2 Wednesday 05 December 2012 10:30 Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers The Clive Pavilion Ludlow Racecourse Ludlow SY8 2BT Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers (Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 2) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1001 Rugby League tickets, postcards and handbooks Rugby 1922 S C R L Rugby League Medal C Grade Premiers awarded League Challenge Cup Final tickets 6th May 1950 and 28th to L McAuley of Berry FC. April 1956 (2 tickets), 3 postcards – WS Thornton (Hunslet), Estimate: £50.00 - £65.00 Hector Crowther and Frank Dawson and Hunslet RLFC, Hunslet Schools’ Rugby League Handbook 1963-64, Hunslet Schools’ Rugby Union 1938-39 and Leicester City v Sheffield United (FA Cup semi-final) at Elland Road 18th March 1961 (9) Lot: 1002 Estimate: £20.00 - £30.00 Keighley v Widnes Rugby League Challenge Cup Final programme 1937 played at Wembley on 8th May. Widnes won 18-5. Folded, creased and marked, staple rusted therefore centre pages loose. Lot: 1009 Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 A collection of Rugby League programmes 1947-1973 Great Britain v New Zealand 20th December 1947, Great Britain v Australia 21st November 1959, Great Britain v Australia 8th October 1960 (World Cup Series), Hull v St Helens 15th April Lot: 1003 1961 (Challenge Cup semi-final), Huddersfield v Wakefield Rugby League Championship Final programmes 1959-1988 Trinity 19th May 1962 (Championship final), Bradford Northern including 1959, 1960, 1968, 1969, 1973, 1975, 1978 and -

Official Handbook 2019/2020 Title Partner Official Kit Partner

OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2019/2020 TITLE PARTNER OFFICIAL KIT PARTNER PREMIUM PARTNERS PARTNERS & SUPPLIERS MEDIA PARTNERS www.leinsterrugby.ie | From The Ground Up COMMITTEES & ORGANISATIONS OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2019/2020 Contents Leinster Branch IRFU Past Presidents 2 COMMITTEES & ORGANISATIONS Leinster Branch Officers 3 Message from the President Robert Deacon 4 Message from Bank of Ireland 6 Leinster Branch Staff 8 Executive Committee 10 Branch Committees 14 Schools Committee 16 Womens Committee 17 Junior Committee 18 Youths Committee 19 Referees Committee 20 Leinster Rugby Referees Past Presidents 21 Metro Area Committee 22 Midlands Area Committee 24 North East Area Committee 25 North Midlands Area Committee 26 South East Area Committee 27 Provincial Contacts 29 International Union Contacts 31 Committee Meetings Diary 33 COMPETITION RESULTS European, UK & Ireland 35 Leagues In Leinster, Cups In Leinster 39 Provincial Area Competitions 40 Schools Competitions 43 Age Grade Competitions 44 Womens Competitions 47 Awards Ball 48 Leinster Rugby Charity Partners 50 FIXTURES International 51 Heineken Champions Cup 54 Guinness Pro14, Celtic Cup 57 Leinster League 58 Seconds League 68 Senior League 74 Metro League 76 Energia All Ireland League 89 Energia Womens AIL League 108 CLUB & SCHOOL INFORMATION Club Information 113 Schools Information 156 www.leinsterrugby.ie 1 OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2019/2020 COMMITTEES & ORGANISATIONS Leinster Branch IRFU Past Presidents 1920-21 Rt. Rev. A.E. Hughes D.D. 1970-71 J.F. Coffey 1921-22 W.A. Daish 1971-72 R. Ganly 1922-23 H.J. Millar 1972-73 A.R. Dawson 1923-24 S.E. Polden 1973-74 M.H. Carroll 1924-25 J.J. Warren 1974-75 W.D. -

History of the Emerald Warriors

1 President: Richie Whyte This was one of our first training sessions as a club. 2003 Captain: Richie Whyte The first session was held on 03 September with five members in the War Memorial Park. The first Quiz Night Fundraiser Emerald Warriors RFC took place on 10 December was Founded. in the Irish Film institute. August The First Meet of the Club was on Thursday 21 August. The first ever AGM was held in The Opera Theatre on 03 October. 2 President: Richie Whyte 2004 Captain: Richie Whyte Inaugural Rugby Clinic held in Old Belvedere attended by teams from Took part in our first England and Scotland. Competed in the Dublin Pride. June Bingham Cup in London. January July Became the eigth nation to join IGRAB. First Official Game vs London Steelers. First official win vs Gotham Knights (10-5). 3 President: Richie Whyte President: Richie Whyte 2005 Captain: Richie Whyte 2006 Captain: Steve Gardner Attended the London Steelers Rugby Raised €686 for Competed in the Clinic. BelongTo by Bingham Cup New York. June carol singing. December July Attended the Union Cup in Montpellier. Attended the Thebans Ranked fourth in Europe. Rugby Clinic Weekend in Edinburgh. 4 Became the first LGBT Rugby Team to join the Leinster Metro League. President: Barry Joyce 2007 Captain: Ciaran O’ Sullivan Queering the Pitch: Union Cup Copenhagen Emerald Warriors featured in Warriors Beat Cardiff Lions in this TG4 Documentary. the final game. April March May September We held our first ever Warriors Win the Tea Dance fundraiser in Bristol 10s Rugby The Dragon. Tournament. -

Scottish Rugby Union Matches and Events Approved for 2019 Close Time Period

Scottish Rugby Union Matches and Events Approved for 2019 Close Time Period No. Scottish Club / Event Organiser Match/Event Match/Event Date Approval Date 001-19 Stewarts Melville RFC (P7’s) Clusone RFC Italy ( Tour ) 25 & 26 May 2019 12 November 2018 002-19 Biggar RFC Biggar RFC Sevens 25 May 2019 16 January 2019 003-19 Hutchesons' Grammar School Tour to South Africa - (Tour) 19 to 31 July 2019 6 February 2019 004-19 Moffat RFC Moffat Tens Tournament 27 July 2019 13 February 2019 005-19 Stirling County RFC Meet in the Middle Girls Sevens Festival 26 May 2019 18 February 2019 006-19 Edinburgh College RFC Algarve Sevens (Tour) 8th & 9th June 2019 6 March 2019 007-19 Boroughmuir HS (U18) Tour to Canada 31 May to 12 June 2019 8 March 2019 008-19 High School of Glasgow (U18 & U16) South Africa (Tour) 20 July to 1 August 2019 10 March 2019 009-19 High School of Dundee (U18 & U16) South Africa (Tour) 27 July to 9 August 2019 11 March 2019 010-19 Melrose Rugby Club (U18) France (Tour) 2 to 5 June 2019 13 March 2019 011-19 Bannockburn RFC Junior Section End of Season Awards Day 1 June 2019 14 March 2019 012-19 Shetland RFC (U15/16) Tour to France (Tour) 13 to 17 June 2019 21 March 2019 013-19 Peebles Rugby Club Tour to France (Tour) 31 May to 3 June 2019 21 March 2019 014-19 Strathendrick RFC (U13) Tour to Ireland (Tour) 30 May to 1 June 2019 2 April 2019 015-19 Heriot’s Rugby Club Benidorm Sevens (Tour) 24 to 27 May 2019 2 April 2019 016-19 Dalziel RFC Warsaw Frogs Tournament (Tour) 24 to 27 May 2019 4 April 2019 017-19 Rugby Ecosse Feminine -

The Welsh Rugby Union Limited Annual Report 2007 Adroddiad Blynyddol 2007 Undeb Rygbi Cymru Cyf Contents

The Welsh Rugby Union Limited Annual Report 2007 Adroddiad Blynyddol 2007 Undeb Rygbi Cymru Cyf Contents Financial highlights 02 Chairman’s review 04 Group Chief Executive’s overview 06 Taking Wales to the world Operating and Financial Review 11 with our rugby Directors’ report 44 Consolidated profit and loss account 46 Balance sheets 47 Welcoming the world to Consolidated cash flow statement 48 Consolidated statement of total recognised gains and losses 49 Wales in our stadium Reconciliation of movement in consolidated capital and reserves 49 Notes to the financial statements 50 Independent auditors’ report 71 Defining Wales as a nation Welsh Rugby Union governance 72 Registered office and advisers 75 Obituaries 76 Business Partners 80 THE WELSH RUGBY UNION LIMITED - ANNUAL REPORT 2007 1 Financial highlights Profit & loss extract - 2006 & 2007 Turnover analysis - 2006 & 2007 4% 1% Analysis of turnover 5% 1% 50 50 10% 46.1 0.3 55% 45 0.4 2.4 13% 57% 43.8 1.7 40 4.3 6.1 Match income Turnover GoveGrnment 40 35 related grants 8.4 8.1 Competition income Operational Costs 30 3.3 Other income 19% M 4.7 25 2007Commercial income 2006 Allocations to £ 30 affiliated 20 Other event income Other event income 17% M organisations 15 25.8 24.2 Commercial income £ 22.7 22.2 Other income Amount remaining 10 20 to service other costs 5 Competition income Government related grants 11% 7% 14.9 0 2007 2006 Match income 11.8 12.1 Year 10 6.2 Operational costs - 2006 & 2007 Operational costs 9% 10% 0 2007 2006 25 Year 29% 12% 28% 12% 20 4.3 4.1 Business & administration -

Please Click Here to Download Our Bid Document

Your Union Cup Your Union Cup 9 CENTRED 28 ON THE CHANGING GRASS AMAZING GAY SCENE ROOMS PITCHES NIGHTLIFE HOME OF RUGBY SINGLE ALL SITE BUDGETS ICONIC HOTELS CATERED OPENING LOCATION FOR CEREMONY VENUE EASY TO EARLY GET HERE BIRD REGISTRATION 29TH APRIL ONLY £100 to 2ND MAY DIVERSE 2021 CITY 1 Your Union Cup Your Union Cup 9 CENTRED 28 ON THE CHANGING GRASS AMAZING GAY SCENE ROOMS PITCHES NIGHTLIFE HOME OF RUGBY SINGLE ALL SITE BUDGETS ICONIC HOTELS CATERED OPENING LOCATION FOR CEREMONY VENUE EASY TO EARLY GET HERE BIRD REGISTRATION 29TH APRIL ONLY £100 to 2ND MAY DIVERSE 2021 CITY 2 Regular shuttle buses from the Overview 1-2 gay village will be put on to the David Cumpston tournament venue free of charge Chairman Birmingham Bulls RFC Contents 3 to attendees. This is in close walking distance to city centre hotels and easily accessible via Welcome 4 public transport. Letter of Intent/Forward The Tournament 5-6 Dear friends, James Anthony Alistair Burford BID CHAIRMAN BID DIRECTOR One Venue 7 Over the past 8yearsBirminghamBullsRFChasdevelopedinto a rugby clubbasedat the heart of Birminghamʼsgay community, that takesitsrugby asseriously asthe social aspectsof our beloved At the Venue 8 game. Off the Pitch 9 We have brought our partnersfromacross the city and aroundour regiontogether inorder to buildthe tournament youwant, here inBirmingham. The Union Cuphasdevelopedfromits beginningsinMontpellier in2005, into the huge tournament we know today. The rapidrecent The Vibrant Scene 10 expansionin numbersof inclusive teams acrossour continent atteststo, andfuelsthe successof thistournament. David Cumpston Samuel Hampton Exploring the City 11 PARTNERSHIPS DIRECTOR MARKETING DIRECTOR Birminghamisa city full of energy andenthusiasm, well-practicedat hostingmajor sporting, and Ceremonies 12 cultural events. -

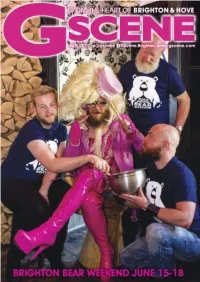

Gscene out & About

GSCENE 3 JUN 2017 CONTENTS GSCENE magazine MARINE TAVERN ) www.gscene.com t @gscene f GScene.Brighton PUBLISHER Peter Storrow TEL 01273 749 947 EDITORIAL [email protected] ADS+ARTWORK [email protected] EDITORIAL TEAM James Ledward, Graham Robson, Gary Hart, Alice Blezard SPORTS EDITOR Paul Gustafson E N ARTS EDITOR Michael Hootman I L B SUB EDITOR Graham Robson U S DESIGN Michèle Allardyce BAR REVENGE FRONT COVER MODELS Ant Howells, Robert Lane, NEWS Tom Bald, Bruce McCrann PHOTOGRAPHER Jack Lynn 6 News Concept & Design: Peter McEachern, Fixer: Graham Munday SCENE LISTINGS CONTRIBUTORS Simon Adams, Jaq Bayles, Jo Bourne, 26 Gscene Out & About Nick Boston, Suchi Chatterjee, Craig Hanlon-Smith, Samuel Hall, 28 Brighton & Hove Enzo Marra, Mike Mendoza, Carl Oprey, Eric Page, Del Sharp, Gay 42 Solent Socrates, Brian Stacey, Michael Steinhage, Sugar Swan, Glen Stevens, DOCTOR BRIGHTONS Duncan Stewart, Craig Storrie, Mike ARTS Wall, Netty Wendt, Roger Wheeler 46 Arts News PHOTOGRAPHERS Alice Blezard, Jack Lynn, Hugo 47 Arts Jazz Michiels, Stella Pix, Graham Hobson @captaincockroachphotographer, 47 Arts Matters 48 Classical Notes 49 Page’s Pages GARY PARGETER 50TH BIRTHDAY PICNIC, QUEENS PARK REGULARS 45 Dance Music © GSCENE 2017 All work appearing in Gscene Ltd is 45 DJ Profile: Lady B copyright. It is to be assumed that the copyright for material rests with the 50 Geek Scene magazine unless otherwise stated on the page concerned. 51 Shopping No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in an electronic or 53 Craig’s Thoughts other retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, 54 Charlie Says mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior knowledge and consent of the publishers. -

Sponsorship Pack the Hull Roundheads RUFC

Sponsorship Pack The Hull Roundheads RUFC • Founded in Hull, East Yorkshire, August 2018 • AIM: joining a global community of Inclusive Rugby where men and women of any gender, sexuality and race can come together for the love of the sport and get into rugger. • CURRENTLY: At present, we are just forming a men’s team, but hopefully if demand is there, we will have a women’s team! • OPEN TO: it doesn’t matter if you’re gay, bi, straight or trans, The Roundheads is a family that brings people together for one purpose, to play rugby and to have fun playing the sport! Whether youa have played all your life or never played before, we have a coaching team that will be able to guide you through or brush up your rugby skills. WHY THE NAME ROUNDHEADS? Hull has an incredibly rich history and association with rugby, which is why we felt we needed to put the city’s stamp into the world of Inclusive Rugby. The name is a nod to our city’s history. During the English Civil War, The Ridings of Yorkshire in Northern England were all Royalists, i.e. they supported the King’s forces over Parliament soldiers aka The Roundheads so named because of the shape of their helmets. However, during this time the city’s elders refused to grant King Charles I entry into the city and slammed the gates shut and declared their allegiance and support to Parliament and Hull became the base that Oliver Cromwell launched his successful campaign to take the North and win the Civil War. -

GLOBAL SPONSORSHIP Proposal 2020

Logo GLOBAL SPONSORSHIP Proposal 2020 www.IGRugby.org Registered Office: 71 Holland Road, West Ham, London, England E15 3BP, United Kingdom. A WARM WELCOME I’m thrilled to welcome you to International Gay Rugby (IGR) and provide you with information about our rapidly growing, ever-passionate, rugby family that today reaches all four corners of the globe and plays a huge part in thousands of our players’ and supporters’ lives. IGR was founded in October 2000 by a small group of Inclusive Rugby Clubs and, as we approach our third decade, we continue to provide opportunities for members of the LGBTQ+ community to enjoy competitive rugby whilst improving respect and tolerance worldwide. This document aims to provide you with a quick overview of the IGR and the opportunities for your brand to powerfully connect with our global organisation as Official Partner. We are very proud of our community, our people and our purpose and very much look forward to developing a profitable and meaningful relationship together. Your Faithfully, Ben Owen Chair & Trustee International Gay Rugby 2 WE’RE HERE... ....To grow inclusive rugby and achieve equality, diversity and personal development in sport. To do our part to eliminate discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation or identification and to promote good health through the playing of rugby by: Providing opportunities for the LGBTQ+ community to compete in welcoming, inclusive rugby clubs that are primarily LGBTQ+ /LGBTQ+ friendly Eliminating homo & transphobia in rugby through community outreach -

EU Citizenship and Withdrawals from the Union: How Inevitable Is the Radical Downgrading of Rights?

LSE ‘Europe in Question’ Discussion Paper Series EU Citizenship and Withdrawals from the Union: How Inevitable Is the Radical Downgrading of Rights? Dimitry Kochenov LEQS Paper No. 111/2016 June 2016 Editorial Board Dr Abel Bojar Dr Vassilis Monastiriotis Dr Jonathan White Dr Katjana Gattermann Dr Sonja Avlijas All views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the editors or the LSE. The European Institute has led an LSE Commission on the Future of Britain in Europe, which has recently published a series of Reports on the issue of Britain’s membership of the European Union – available at: http://www.lse.ac.uk/europeanInstitute/LSE-Commission/LSE-Commission-on-the-Future- of-Britain-in-Europe.aspx. © Dimitry Kochenov EU Citizenship and Withdrawals from the Union: How Inevitable Is the Radical Downgrading of Rights? Dimitry Kochenov * Abstract What are the likely consequences of Brexit for the status and rights of British citizenship? Can the fact that every British national is an EU citizen mitigate the possible negative consequences of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU on the plane of rights enjoyed by the citizens of the UK? These questions are not purely hypothetical, as the referendum on June 23 can potentially mark one of the most radical losses in the value of a particular nationality in recent history. This paper reviews the possible impact that the law and practice of EU citizenship can have on the conduct of Brexit negotiations and surveys the possible strategies the UK government could adopt in extending at least some EU-level rights to UK citizens post-Brexit. -

Human Rights and Climate Change : EU Policy Options

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES OF THE UNION DIRECTORATE B POLICY DEPARTMENT STUDY HUMAN RIGHTS AND CLIMATE CHANGE: EU POLICY OPTIONS Abstract Our study provides a survey of the state of the relationships currently established between human rights and climate change. It examines the external diplomacy of the European Union in the fields of human rights and climate change. The relationship between these two fields is addressed from two different perspectives: the integration of the climate change topic within EU human rights diplomacy; and the inclusion of human rights concerns within EU climate change diplomacy. We analyse its effectiveness, efficiency and the interrelationships with the EU’s external development policy by showing, where appropriate, their coordination, coherence and mutual support. In this respect, special emphasis is put on migration issues. Our study then turns the analysis towards internal EU climate change policies, which are explored from the perspective of human rights. We assess the compatibility of European Union mitigation policies with human rights and the gradual integration of the EU adaptation framework within other key European Union policies. Finally, this work concludes with a clarification of how the environmental human right to public information and participation in decision-making, which is transversal by nature, appears and may evolve in both EU internal and external climate policy. EXPO/B/DROI/2011/20 /August/ 2012 PE 457.066 EN Policy Department DG External Policies This study was requested by the European Parliament's Subcommittee on Human Rights. COORDINATORS Christel COURNIL (Team leader), Associate Professor of public law at the University Paris 13 - Pres Sorbonne Paris Cité, member of Iris (Institute for Interdisciplinary Research on social issues) and associate researcher at the CERAP (Centre for Administrative and Political Studies and Research). -

Thesis Structure

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The legal governance of historical memory and the rule of law Bán, M. Publication date 2020 Document Version Final published version License Other Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bán, M. (2020). The legal governance of historical memory and the rule of law. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:07 Oct 2021 The Legal Governance of Historical Memory and the Rule of Law ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. ir. K.I.J. Maex ten overstaan van een door het College voor Promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op woensdag 21 oktober 2020, te 13.00 uur door Marina Bán geboren te Budapest Promotiecommissie Promotor: prof.