Codman Square: History (1630 to Present), Turmoil (1950-1980)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Umass Boston Community Guide

UMass Boston Community Guide _________________________________________________ OFFICE OF STUDENT HOUSING _________________________________________________ 100 Morrissey Boulevard Boston, MA 02125-3393 OFFICE OF STUDENT HOUSING P: 617.287.6011 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS BOSTON F: 617.287.6335 E: [email protected] www.umb.edu/housing CONTENTS Boston Area Communities 3 Dorchester 3 Quincy 4 Mattapan 5 Braintree 6 South Boston 7 Cambridge 8 Somerville 9 East Boston 10 Transportation 11 MBTA 11 Driving 12 Biking 12 Trash Collection & Recycling 13 Being a Good Neighbor 14 Engage in Your Community 16 Volunteer 16 Register to Vote 16 Community Guide | Pg 2 100 Morrissey Boulevard Boston, MA 02125-3393 OFFICE OF STUDENT HOUSING P: 617.287.6011 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS BOSTON F: 617.287.6335 E: [email protected] www.umb.edu/housing BOSTON AREA COMMUNITIES Not sure what neighborhood to live in? This guide will introduce you to neighborhoods along the red line (the ‘T’ line that serves UMass Boston), as well as affordable neighborhoods where students tend to live. Visit these resources for more information on neighborhoods and rental costs in Boston: Jumpshell Neighborhoods City of Boston Neighborhood Guide Rental Cost Map Average Rent in Boston Infographic Dorchester: Andrew – JFK/UMass – Savin Hill – Fields Corner – Shawmut, Ashmont, Ashmont-Mattapan High Speed Line Dorchester is Boston’s largest and oldest neighborhood, and is home to UMass Boston. Dorchester's demographic diversity has been a well-sustained tradition of the neighborhood, and long-time residents blend with more recent immigrants. A number of smaller communities compose the greater neighborhood, including Codman Square, Jones Hill, Meeting House Hill, Pope's Hill, Savin Hill, Harbor Point, and Lower Mills. -

2017 Stormwater Management Report

Municipality/Organization: Boston Water and Sewer Commission EPA NPDES Permit Number: MASO 10001 Report/Reporting Period: January 1, 2017-December 31, 2017 NPDES Phase I Permit Annual Report General Information Contact Person: Amy M. Schofield Title: Project Manager Telephone #: 617-989-7432 Email: [email protected] Certification: I certify under penalty of law that this document and all attachments were prepared under my direction or supervision in accordance with a system designed to assure that qualified personnel properly gather and evaluate the information submitted. Based on my inquiry of the person or persons who manage the system, or those persons directly responsible for gathering the information, the information submitted is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, true, accuratnd complete. I am aware that there are significant penalties for submitting false ivfothnation intdng the possibiLity of fine and imprisonment for knowing violatti Title: Chief Engineer and Operations Officer Date: / TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Permit History…………………………………………….. ……………. 1-1 1.2 Annual Report Requirements…………………………………………... 1-1 1.3 Commission Jurisdiction and Legal Authority for Drainage System and Stormwater Management……………………… 1-2 1.4 Storm Drains Owned and Stormwater Activities Performed by Others…………………………………………………… 1-3 1.5 Characterization of Separated Sub-Catchment Areas….…………… 1-4 1.6 Mapping of Sub-Catchment Areas and Outfall Locations ………….. 1-4 2.0 FIELD SCREENING, SUB-CATCHMENT AREA INVESTIGATIONS AND ILLICIT DISCHARGE REMEDIATION 2.1 Field Screening…………………………………………………………… 2-1 2.2 Sub-Catchment Area Prioritization…………………………………..… 2-4 2.3 Status of Sub-Catchment Investigations……………………….…. 2-7 2.4 Illicit Discharge Detection and Elimination Plan ……………………… 2-7 2.5 Illicit Discharge Investigation Contracts……………….………………. -

St. Marks Area (Ashmont/Peabody Square), Dorchester

Commercial Casebook: St Marks Area Historic Boston Incorporated, 2009-2011 St. Marks Area (Ashmont/Peabody Square), Dorchester Introduction to District St. Mark's Main Street District spans a mile-long section of Dorchester Avenue starting from Peabody Square and running north to St. Mark’s Roman Catholic Church campus. The district includes the residential and commercial areas surrounding those two nodes. The area, once rural farmland, began to develop after the Old Colony railroad established a station here in the 1870s. Subsequent trolley service and later electrified train lines, now the MBTA's red line, transformed the neighborhood district into first a “Railroad Suburb” and then a “Streetcar Suburb.” Parts of the area are characterized as “Garden Districts” in recognition of the late 19th century English-inspired development of suburban districts, which included spacious single-family houses built on large lots and the commercial district at Peabody Square. Other areas reflect Boston’s general urban growth in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with densely clustered multi-family housing, including Dorchester’s famous three-deckers, found on the streets surrounding St. Mark’s Church. The district, particularly in Peabody Square, features many late 19th-century buildings, including the landmark All Saints’ Episcopal Church, the Peabody Apartments, a fire station, and a distinctive market building. These surround a small urban park with a monument street clock. The St. Mark’s campus, established a few decades later, mostly in the 1910s and 1920s, is a Commercial Casebook: St Marks Area Historic Boston Incorporated, 2009-2011 collection of ecclesiastical buildings set upon a large, airy parcel. -

Morrissey Boulevard Redesign for Reconstruction Deadline Extended to April 22, 2016

Morrissey Boulevard Redesign for Reconstruction deadline extended to April 22, 2016 Date and Time Topic on Which You are Comment Name Address City State Zip Email I would like to Submitting Your Comment receive future DCR updates 3/29/16 1:07 PM Morrissey Boulevard Redesign In the segment of Morrissey Boulevard near Savin Hill, please allow a left turn from Old David Eaton 81 Tuttle Street Dorchester MA 02125 [email protected] Please add my contact for Reconstruction - deadline Colony Terrace onto Morrissey Boulevard. It looks like there will be a new signal that will Dorchester, MA 02125 information to an April 18, 2016 hopefully allow this, but I would like to confirm. Currently, residents of Savin Hill are forced US outreach list on the to take a right turn onto Morrissey, then make a U-Turn on Freeport Street. Currently, selected topic, in order driving from Savin Hill to UMASS, the JFK Library, BC High, Day Boulevard and Star to receive future DCR Market is very inconvenient! updates and public meeting notices on the topic 3/29/16 9:01 PM Morrissey Boulevard Redesign I could not make the meeting but did read the presentation. Robb Ross 18-20 Southview St, Savinhill Boston MA 02125 [email protected] Please add my contact for Reconstruction - deadline Boston, MA 02125 information to an April 18, 2016 This area is a treasure that could use improvement for recreation and for transit. US outreach list on the selected topic, in order We own property in the area that has been in our family for 80 years or more and we fully endorse to receive future DCR the vision that the DCR is proposing. -

District Journal for Aug 13, 2021 - Aug 16, 2021, District: ALL

District Journal for Aug 13, 2021 - Aug 16, 2021, District: ALL Date: Reported Record Count: 633 Report Date & Time Complaint # Occurrence Date & Time Officer 8/13/2021 12:19:38 AM 212656547-00 8/12/2021 11:25:00 PM 012214 MICHAEL SULLIVAN Location of Occurrence 40 GIBSON ST Nature of Incident AUTO THEFT - MOTORCYCLE / SCOOTER Report Date & Time Complaint # Occurrence Date & Time Officer 8/13/2021 12:40:10 AM 212056549-00 8/12/2021 11:44:00 PM 153122 CHRISTOPHER MYERS Location of Occurrence 145 ASHMONT ST Nature of Incident HARASSMENT/ CRIMINAL HARASSMENT Report Date & Time Complaint # Occurrence Date & Time Officer 8/13/2021 12:40:55 AM 212056545-00 8/12/2021 11:42:00 PM 099769 RICHARD CABAN Location of Occurrence 81 WALNUT PARK Nature of Incident INVESTIGATE PROPERTY Report Date & Time Complaint # Occurrence Date & Time Officer 8/13/2021 12:53:15 AM 212056551-00 8/12/2021 11:51:00 PM 153117 STANLEY PINA Location of Occurrence 19 BARRY ST Nature of Incident M/V ACCIDENT - INVOLVING PEDESTRIAN - INJURY Report Date & Time Complaint # Occurrence Date & Time Officer 8/16/2021 3:09:45 PM Boston Police Department 8/13/2021 1:04:58 AM 212056472-00 8/12/2021 6:24:00 PM 106678 REIVILO DEGRAVE Location of Occurrence 233 D STREET Nature of Incident FIREARM/WEAPON - FOUND OR CONFISCATED Arrests Jamarie Davis 8S SELON DORCHESTER MA Malachi White 38 WARWICK QUINCY MA Report Date & Time Complaint # Occurrence Date & Time Officer 8/13/2021 1:06:05 AM 212056552-00 8/13/2021 12:04:00 AM 010700 STEPHEN BORBEE Location of Occurrence NORTON ST & RIVER ST -

Elderly-Disabled Development Descriptions

BOSTON HOUSING AUTHORITY Housing Applications Elderly/Disabled Development Descriptions For Your Information: In order to qualify for federally assisted Elderly/Disabled housing, the head or co-head must be 62 years of age or older, or handicapped/disabled. In order to qualify for our three State assisted Elderly/Disabled sites: Basilica, Franklin Field, Msgr. Powers, the head or co-head must be 60 years of age or older or handicapped/disabled. Pursuant to State Law, in each of these three State assisted complexes, only 13.5% of the units available for occupancy can be occupied by households whose head is a non-elderly, handicapped/disabled person and 86.5% of the units are available, “Designated” for elderly who are 60 years of age or older. Consequently, handicapped/disabled applicants will have a much longer wait for placement in these three State assisted developments than applicants who are 60 years of age or older. The Waiting List for 2 bedroom units is very long at all Elderly/Disabled developments. In addition to the developments that have hot lunch and/or health care services on-site, Meals on Wheels are available to qualified residents of these developments. Most of the developments that do not have on-site coordination of community based services do provide blood pressure screening and sight and hearing tests on a regular basis as well as some podiatrist. Shopping trips are also available to the residents in many of these locations. Designated Housing means that Elderly applicants 62 years of age or older will be have preference over the applicants under 62 years of age at the Development(s) indicating “YES” under that column. -

Residences on Morrissey Boulevard, 25 Morrissey Boulevard, Dorchester

NOTICE OF INTENT (NOI) TEMPORARY CONSTRUCTION DEWATERING RESIDENCES AT MORRISSEY BOULEVARD 25 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD DORCHESTER, MASSACHUSETTS by Haley & Aldrich, Inc. Boston, Massachusetts on behalf of Qianlong Criterion Ventures LLC Waltham, Massachusetts for US Environmental Protection Agency Boston, Massachusetts File No. 40414-042 July 2014 Haley & Aldrich, Inc. 465 Medford St. Suite 2200 Boston, MA 02129 Tel: 617.886.7400 Fax: 617.886.7600 HaleyAldrich.com 22 July 2014 File No. 40414-042 US Environmental Protection Agency 5 Post Office Square, Suite 100 Mail Code OEP06-4 Boston, Massachusetts 02109-3912 Attention: Ms. Shelly Puleo Subject: Notice of Intent (NOI) Temporary Construction Dewatering 25 Morrissey Boulevard Dorchester, Massachusetts Dear Ms. Puleo: On behalf of our client, Qianlong Criterion Ventures LLC (Qianlong Criterion), and in accordance with the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Remediation General Permit (RGP) in Massachusetts, MAG910000, this letter submits a Notice of Intent (NOI) and the applicable documentation as required by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for temporary construction site dewatering under the RGP. Temporary dewatering is planned in support of the construction of the proposed Residences at Morrissey Boulevard in Dorchester, Massachusetts, as shown on Figure 1, Project Locus. We anticipate construction dewatering will be conducted, as necessary, during below grade excavation and planned construction. The site is bounded to the north by the JFK/UMass MBTA red line station, to the east by William T. Morrissey Boulevard, to the south by paved parking associated with Shaw’s Supermarket, beyond which lies the Shaw’s Supermarket, and to the west by MBTA railroad tracks and the elevated I-93 (Southeast Expressway). -

Improved Soldiers Field Road Crossings

Improved Soldiers Field Road Crossings DCR Public Meeting Monday, November 19th – 6:00pm-7:30pm Josephine A. Fiorentino Community Center Charlesview Residences 123 Antwerp Street Extension, Brighton, MA 02135 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Governor Charles D. Baker Lieutenant Governor Karyn E. Polito Energy and Environmental Secretary Matthew A. Beaton Department of Conservation and Recreation Commissioner Leo P. Roy DCR Mission Statement To protect, promote and enhance our common wealth of natural, cultural and recreational resources for the well-being of all. Purpose of Public Meeting • Project Overview • Overview of Public Input from Previous Outreach Efforts • Design Options for Telford Street Crossing • Proposed Concept • Input from Public Soldiers Field Road Crossings 1. Public Input after Meeting #1 – why revisit the design concept? 2. At-Grade Crossing at Telford Street – what will this look like? 3. Design and Construction Methods – how will changes to design affect construction? Project Partners Harvard’s Total Contribution: $ 3,500,000 Feasibility Study: -$ 150,000 Total Project Allocation: $ 3,350,000 Initial Improvements Concept Initial Improvements Concept Initial Improvements Concept Public Input from Meeting #1 Overall support for the project, but with comments Connections to the river should accommodate cyclists, pedestrians, and disabled users Bridge rehabilitation will leave bridge too narrow and ramp switchbacks too difficult to accommodate bicycles, strollers, and pedestrians Desire for more landscaping throughout -

Work to Install Jamaicaway Traffic Light Set to Begin in November - Jamaica Plain - Your Town - Boston.Com

Work to install Jamaicaway traffic light set to begin in November - Jamaica Plain - Your Town - Boston.com YOUR TOWN (MORE TOWNS) Sign In | Register now Jamaica Plain home news events discussions search < Back to front page Text size – + Connect to Your Town Jamaica Plain on Facebook Like You like Your Town Jamaica Plain. Unlike · Admin Page · Error JAMAICA PLAIN You and 17 others like this 17 people like this Work to install Jamaicaway ADVERTISEMENT traffic light set to begin in November Posted September 16, 2010 03:43 PM E-mail | Link | Comments (0) Ads by Google what's this? GE LED Traffic Signals Up to 90% energy-cost savings and a long-life of up to 50,000 hours. ecomagination.com/LED_Traffic_Light Jamaica Plain Condos Condo & Single Family Sales Jamaica Plain Neighborhood Experts www.RobertaStone.com (Courtesy DCR) ADVERTISEMENT Initial plans shown at a January public meeting for changes to the intersection of Jamaicaway and Eliot Street. By Matt Rocheleau, Town Correspondent The installation of a pedestrian-activated traffic light and other roadwork at the intersection of the Jamaicaway and Eliot Street is set to begin in November. The project is scheduled to be finished in the spring and includes the traffic signal, roadway realignments, median alterations, new signs, and steps to make the intersection more handicapped-accessible. The price tag for the construction is expected to be around $170,000, according to the Department of Conservation and Recreation, which is using its capital funds to pay for the project. Jamaica Plain Headlines The conservation department is soliciting bids and expects to award a contract for the work this fall, spokeswoman Wendy Fox said. -

From: Murray Shafiroff <[email protected]> Sent

From: Murray Shafiroff <[email protected]> Sent: Wednesday, April 08, 2015 6:53 AM EDT To: Alexandros Pelekanakis <Alexandros Pelekanakis <[email protected]>>; Anne Vaillancourt <Anne Vaillancourt <[email protected]>>; Brett Haynes <Brett Haynes <[email protected]>>; Brian Barcelou <Brian Barcelou <[email protected]>>; Brian Henry <Brian Henry <[email protected]>>; Dan Rothman <Dan Rothman <[email protected]>>; Daniel Keeler <Daniel Keeler <[email protected]>>; Don Burgess <Don Burgess <[email protected]>>; Eric Johnson <Eric Johnson <[email protected]>>; Francisco Skelton <Francisco Skelton <[email protected]>>; Garrett Larkin <Garrett Larkin <[email protected]>>; Jarrod Fullerton <Jarrod Fullerton <[email protected]>>; Jason Marshall <Jason Marshall <[email protected]>>; Jeff Beers <Jeff Beers <[email protected]>>; Jerry Turner <Jerry Turner <[email protected]>>; Jim Fitzpatrick <Jim Fitzpatrick <[email protected]>>; Keith Sullivan <Keith Sullivan <[email protected]>>; Larry Louis <Larry Louis <[email protected]>>; Mark Hammond <Mark Hammond <[email protected]>>; Michael Driscoll <Michael Driscoll <[email protected]>>; Michael Kane <Michael Kane <[email protected]>>; Nelson Vasconcelos <Nelson Vasconcelos <[email protected]>>; Richard Reidy <Richard Reidy <[email protected]>>; Shawn Romanoski <Shawn Romanoski <[email protected]>>; Stephanie Nappi <Stephanie Nappi <[email protected]>>; -

Chapter 3—Existing Conditions: Bowker Overpass

Massachusetts Turnpike Boston Ramps and Bowker Overpass Study December 2015 Chapter 3—Existing Conditions: Bowker Overpass 3.1 INTRODUCTION This chapter describes the analysis of the Bowker Overpass sub-area of the Massachusetts Turnpike — Boston Ramps Study. As in Chapter 2, which discusses the larger study area, this section summarizes existing transportation conditions during a typical workday, emphasizing the peak-commuting hour. This section also reviews crash data and land use conditions. The Transit Data and Environmental Conditions provided in Chapter 2 apply to the Bowker Overpass sub-area of the study. 3.2 TRAFFIC CONDITIONS Developing a base knowledge of current traffic conditions fosters an understanding of where congestion occurs now and where it likely would occur in the future. The first step in calculating traffic congestion requires using current or recent turning- movement and traffic counts. Traffic counts were obtained along the Massachusetts Turnpike between the Allston Tolls and Ted Williams Tunnel, and at specific intersections throughout the study area. The volumes used in this analysis are presented in Section 3.2.1. Section 3.2.2 summarizes system performance. 3.2.1 Existing (2010) Traffic Volumes The Bowker Overpass delineates the Back Bay and Fenway/Kenmore neighborhoods, and runs roughly along the Muddy Brook between the Emerald Necklace/Back Bay Fens and the Charles River Esplanade. It connects Boylston Street and Fenway with Storrow Drive over the Massachusetts Turnpike, Commonwealth Avenue, and Beacon Street (Figure 3-1). The Bowker is also known as the Charlesgate Overpass, as Charlesgate is the name of the roadway that the overpass carries. -

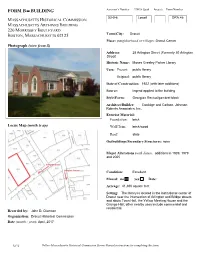

FORM B BUILDING Assessor’S Number USGS Quad Area(S) Form Number

FORM B BUILDING Assessor’s Number USGS Quad Area(s) Form Number 52-0-6 Lowell DRA.46 MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION MASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES BUILDING 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD Town/City: Dracut BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 Place: (neighborhood or village): Dracut Center Photograph (view from S) Address: 28 Arlington Street (Formerly 30 Arlington Street) Historic Name: Moses Greeley Parker Library Uses: Present: public library Original: public library Date of Construction: 1922 (with later additions) Source: legend applied to the building Style/Form: Georgian Revival/gambrel block Architect/Builder: Coolidge and Carlson, Johnson Roberts Associates, Inc. Exterior Material: brick Foundation: Locus Map (north is up) Wall/Trim: brick/wood Roof: slate Outbuildings/Secondary Structures: none Major Alterations (with dates): additions in 1939, 1979 and 2005 Condition: Excellent Moved: no yes Date: Acreage: 41,300 square feet Setting: The library is located in the institutional center of Dracut near the intersection of Arlington and Bridge streets and abuts Town Hall, the Yellow Meeting House and the Grange Hall; other nearby uses include commercial and residential. Recorded by: John D. Clemson Organization: Dracut Historical Commission Date (month / year): April, 2017 12/12 Follow Massachusetts Historical Commission Survey Manual instructions for completing this form. INVENTORY FORM B CONTINUATION SHEET DRACUT 28 ARLINGTON STREET MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Area(s) Form No. 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD, BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 DRA.46 Recommended