Common Sense, Contracts, and Law and Literature: Why Lawyers Should Read Henry James

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pluto Cartoons Copyright © 2014 - Allears.Net - Created by Jamesd (Dzneynut) Email the Bonus Clue to [email protected] for a Chance to Win a Disney Pin!

Pluto Cartoons Copyright © 2014 - AllEars.net - Created by JamesD (dzneynut) Email the bonus clue to [email protected] for a chance to win a Disney pin! 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 9 10 3 4 5 11 12 13 14 6 15 16 7 17 18 8 19 9 10 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 short Chain Gang Moose Hunt Rover feed me Minnie kiss me Lend a Paw Dinah Pluto Fifi Private Dutch pekinese dachshund retriever cats Pete mice True bumblebee planet Duck Hunt Canine False Navy Army Prince Farmer Zoo Justice brandy humanized whisky bone goat Gunther bull skates Good Deed tail ears magic hat train Gopher ★ What type of dog is Pluto? _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Across Down 3. In what 1930 cartoon did Pluto make his first 1. Who did Pluto belong to in the cartoon screen appearance, although he was unnamed? mentioned in #13 Across? (The _____ ____) 2. What branch of the military in 1945 enlists Pluto 4. In "Pluto's Judgement Day," who puts Pluto on to help keep a sharp lookout for intruders in the trial? (jury of ____) animated short, "Dog Watch?" 6. In the 1936 animated cartoon, "Alpine 3. In the 1945 cartoon, "______ Casanova," Pluto Climbers," what does Pluto and the St. Bernard saves his love, Dinah from the Municipal Dog drink? Pound. 8. In "The Picnic," what does 'Pluto' use as a 5. What does Mickey put on Pluto's paws in order windsheld wiper to help save the day? to impress the judges in the 1939 short, "Society 9. -

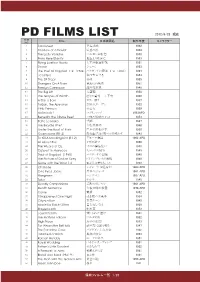

Pd Films List 0824

PD FILMS LIST 2012/8/23 現在 FILM Title 日本映画名 制作年度 キャラクター NO 1 Sabouteur 逃走迷路 1942 2 Shadow of a Doubt 疑惑の影 1943 3 The Lady Vanishe バルカン超特急 1938 4 From Here Etanity 地上より永遠に 1953 5 Flying Leather Necks 太平洋航空作戦 1951 6 Shane シェーン 1953 7 The Thief Of Bagdad 1・2 (1924) バクダッドの盗賊 1・2 (1924) 1924 8 I Confess 私は告白する 1953 9 The 39 Steps 39夜 1935 10 Strangers On A Train 見知らぬ乗客 1951 11 Foreign Correspon 海外特派員 1940 12 The Big Lift 大空輸 1950 13 The Grapes of Wirath 怒りの葡萄 上下有 1940 14 A Star Is Born スター誕生 1937 15 Tarzan, the Ape Man 類猿人ターザン 1932 16 Little Princess 小公女 1939 17 Mclintock! マクリントック 1963APD 18 Beneath the 12Mile Reef 12哩の暗礁の下に 1953 19 PePe Le Moko 望郷 1937 20 The Bicycle Thief 自転車泥棒 1948 21 Under The Roof of Paris 巴里の屋根の根 下 1930 22 Ossenssione (R1.2) 郵便配達は2度ベルを鳴らす 1943 23 To Kill A Mockingbird (R1.2) アラバマ物語 1962 APD 24 All About Eve イヴの総て 1950 25 The Wizard of Oz オズの魔法使い 1939 26 Outpost in Morocco モロッコの城塞 1949 27 Thief of Bagdad (1940) バクダッドの盗賊 1940 28 The Picture of Dorian Grey ドリアングレイの肖像 1949 29 Gone with the Wind 1.2 風と共に去りぬ 1.2 1939 30 Charade シャレード(2種有り) 1963 APD 31 One Eyed Jacks 片目のジャック 1961 APD 32 Hangmen ハングマン 1987 APD 33 Tulsa タルサ 1949 34 Deadly Companions 荒野のガンマン 1961 APD 35 Death Sentence 午後10時の殺意 1974 APD 36 Carrie 黄昏 1952 37 It Happened One Night 或る夜の出来事 1934 38 Cityzen Ken 市民ケーン 1945 39 Made for Each Other 貴方なしでは 1939 40 Stagecoach 駅馬車 1952 41 Jeux Interdits 禁じられた遊び 1941 42 The Maltese Falcon マルタの鷹 1952 43 High Noon 真昼の決闘 1943 44 For Whom the Bell tolls 誰が為に鐘は鳴る 1947 45 The Paradine Case パラダイン夫人の恋 1942 46 I Married a Witch 奥様は魔女 -

Pluto Cartoons Copy

Pluto Cartoons Copyright © 2014 - AllEars.net - Created by JamesD (dzneynut) Email the bonus clue to [email protected] for a chance to win a Disney pin! 1 M 2 N I 3 4 5 C H A I N G A N G C A T S A V N K 6 7 8 B R A N D Y I G T A I L 9 10 I M O O S E H U N T D T 11 12 T N N P L A N E T 13 R O V E R T R C S 14 A Z H I H 15 16 F I F I O P E K I N E S E 17 18 N G O P H E R C H O R T E U 19 H U M A N I Z E D N 20 T V G O O D D E E D 21 22 K F A R M E R 23 M A G I C H A T 24 S L E N D A P A W S S 25 B U M B L E B E E 26 P L U T O E N 27 T R U E short Chain Gang Moose Hunt Rover feed me Minnie kiss me Lend a Paw Dinah Pluto Fifi Private Dutch pekinese dachshund retriever cats Pete mice True bumblebee planet Duck Hunt Canine False Navy Army Prince Farmer Zoo Justice brandy humanized whisky bone goat Gunther bull skates Good Deed tail ears magic hat train Gopher ★ What type of dog is Pluto? [BLOODHOUND] Across Down 3. -

Walt. Disney

CHARLOTTE AND ROBERT DISNEY HOUSE 4406 WEST KINGSWELL AVENUE CHC-2016-2575-HCM ENV-2016-2576-CE Agenda packet includes: 1. Final Staff Recommendation Report 2. Categorical Exemption 3. Director-Initiation Letter, Dated July 20, 2016 4. Nomination 5. 1990 Nomination and Letter of Determination 6. Letter from Member of the Public Please click on each document to be directly taken to the corresponding page of the PDF. Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2016-2575-HCM ENV-2016-2576-CE HEARING DATE: September 15, 2016 Location: 4406 West Kingswell Avenue TIME: 9:00 AM Council District: 4 PLACE: City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: Hollywood 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: Central Los Angeles, CA 90012 Neighborhood Council: Los Feliz/South Los Feliz Legal Description: Mount Hollywood Grandview EXPIRATION DATE: October 3, 2016 Tract No. 2 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the CHARLOTTE AND ROBERT DISNEY HOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER(S): Sang Ho Yoo, Krystal Yoo, and Hyun Bae Kim 3435 Wilshire Boulevard, #1190 Los Angeles, CA 90010 Sang Ho Yoo and Krystal Yoo 4237 Vanetta Drive Studio City, CA 91604 APPLICANT: City of Los Angeles, Planning Department 200 North Spring Street, Room 559 Los Angeles, CA 90012 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Declare the subject property a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.7. 2. Adopt the staff report and findings. VINCENT P. BERTONI, AICP Director of Planning [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. -

Disney (Movies)

Content list is correct at the time of issue DISNEY (MOVIES) 101 Dalmatians (1996) 101 Dalmatians Ii: Patch's London Adventure 102 Dalmatians 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea Absent-Minded Professor, The Adventures Of Bullwhip Griffin, The Adventures Of Huck Finn, The Adventures Of Ichabod And Mr. Toad, The African Cats African Lion, The Aladdin (1992) Aladdin (2019) Aladdin And The King Of Thieves Alexander And The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day Alice In Wonderland (1951) Alice In Wonderland (2010) Alice Through The Looking Glass Alley Cats Strike (Disney Channel) Almost Angels America's Heart & Soul Amy Annie (1999) Apple Dumpling Gang Rides Again, The Apple Dumpling Gang, The Aristocats, The Artemis Fowl Atlantis: Milo's Return Atlantis: The Lost Empire Babes In Toyland Bambi Bambi Ii Bears Bears And I, The Beauty And The Beast (1991) Beauty And The Beast (2017) Beauty And The Beast-The Enchanted Christmas Bedknobs And Broomsticks (Not In Luxembourg) Bedtime Stories Belle's Magical World (1998) Benji The Hunted Beverly Hills Chihuahua Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 Beverly Hills Chihuahua 3: Viva La Fiesta! Big Green, The Big Hero 6 Biscuit Eater, The Black Cauldron, The Content list is correct at the time of issue Black Hole, The (1979) Blackbeard's Ghost Blank Check Bolt Born In China Boy Who Talked To Badgers, The Boys, The: The Sherman Brothers' Story Bride Of Boogedy Brink! (Disney Channel) Brother Bear Brother Bear 2 Buffalo Dreams (Disney Channel) Cadet Kelly (Disney Channel) Can Of Worms (Disney Channel) Candleshoe Casebusters -

Walt Disney and His Influence in the American Society.”

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA, LETRAS Y CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA DE LENGUA Y LITERATURA INGLESA “WALT DISNEY AND HIS INFLUENCE IN THE AMERICAN SOCIETY.” ABSTRACT “Walt Disney and his Influence in the American Society” is a complex topic that is explained in different aspects. All of them are based on special circumstances which are indispensable to understand the beginning, development, and success of this legendary figure. In Chapter One, there is a clear explanation of Disney´s genealogy from 1824 until 1903, his family, education, jobs, voluntary activities, personal life, some exemplifications of his first attempts at artistic talent, and his death. In Chapter Two, there are some definitions of animated cartoons. We analyze the first optical toys as a great asset in the progress of cartoons. Additionally, there is a description of some Disney´s contributions to motion pictures. In Chapter Three, there is a description of Disney´s imagination which is based on folk literature. There is an analysis relied on some of the most important Disney´s creations. In Chapter Four, there is a description of the establishment of the Disney Company in Hollywood. This AUTORAS: ROSA ELENA NIOLA SANMARTÌN MIRIAM ELIZABETH RIVERA CAJAMARCA 1 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA, LETRAS Y CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA DE LENGUA Y LITERATURA INGLESA “WALT DISNEY AND HIS INFLUENCE IN THE AMERICAN SOCIETY.” Company had some wonderful achievements which were a great contribution to the world. However, complicated situations and company failures were present through its development. In the Golden Age of Animation, there were some important Disney characters which represent a great asset in the evolution of sound. -

![Walt Disney Treasures - the Complete Pluto Volume One [2 X DVD] Walt Disney Treasures - the Complete Pluto Volume One [2 X DVD]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4661/walt-disney-treasures-the-complete-pluto-volume-one-2-x-dvd-walt-disney-treasures-the-complete-pluto-volume-one-2-x-dvd-4524661.webp)

Walt Disney Treasures - the Complete Pluto Volume One [2 X DVD] Walt Disney Treasures - the Complete Pluto Volume One [2 X DVD]

Walt Disney Treasures - The Complete Pluto Volume One [2 x DVD] Walt Disney Treasures - The Complete Pluto Volume One [2 x DVD] Gled deg over de animasjonstekniske fremskrittene og fnis deg igjennom 28 klassiske Pluto- tegnefilmer fra 1930- og 40-tallet. Walt Disney Treasures - The Complete Pluto Volume One Bert Gillett, Ben Sharpsteen, Clyde Geronomi, Norm Ferguson, Charles Nichols, Jack Hannah Walt Disney Animation 1930-1947 Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment 4:3 Fullskjerm (1,33:1) Dolby Digital 2.0 204 min. 2 6 En sølvskatt graves frem I serien Walt Disney Treasures kommer nå den evig populære hunden Plutos debut, presentert av animasjonshistoriker Leonard Maltin. Pluto oppsto som mange andre disneyfigurer som en bi- karakter i en kortfilm, men Pluto hadde egenskaper som var en hovedkarakter verdig og ble etter hvert nettopp det i sin egen kortfilmserie, produsert fra midten av tredvetallet og videre opp gjennom tegnekortfilmformatets gullalder. Storparten av filmene du finner på disse to diskene er nettopp fra denne tiden (1935-1945), men det er også et par virkelig tidlige filmer her, hvor man får se Plutos i en svært tidlig utgave. Det hele er lekkert pakket inn i det blinkende sølvcoveret som denne serien etter hvert har blitt så kjent for, og foruten 28 nyrestaurerte episoder finner vi en god del ekstramateriale for den animasjonshistorieglade titter. Det kan være litt vrient å vurdere animerte kortfilmers underholdningsverdi, og spesielt i filmer som er fra en tid da sosiale normer, media og verdenssituasjonen var en ganske annen enn den er i dag. I tillegg kommer diskusjonen om man skal sammenlikne disse filmene opp i mot vanlige filmer eller om man bør sette det animasjonstekniske høyre. -

Spot October 2008.Indd

Spotlight on The Willamette Valley From GUITARS to CAMERAS He makes them LUV-A-BULL Started with a Child’s Dream Dog SHINING MODEL Pro-Bone-O serves pets of the homeless EVERY DOG is a little bit wolf But wolves are not dogs TIME for a Walk in the Art EEVERYTHINGVERYTHING PETPET IINN TTHEHE NNORTHWESTORTHWEST! • OOCTOBERCTOBER 22008008 SPOTLIGHT on The Willamette Valley 20 WOLF HAVEN 10 SHINING MODEL 13 Ruckus Rulz! Every dog is a Pro-Bone-O serves Ruckus raves about shopping in the Tropics and great outdoor little bit wolf, pets of the homeless gear. but wolves are Interestingly, Pro-Bone-O, a not dogs. nonprofi t celebrating a decade of serving the pets of people That’s a fact too many discover who are homeless. is homeless 6 Rescue me! Meet the sweet foundlings who after taking a wolf pup as a pet. itself. But probably not for long. In fi nd their way to Spot at presstime. And while that’s exactly how Wolf addition to a building in its future, Haven’s story began, theirs is a the agency plans to expand its happy ending: what began with reach in important ways. 2 humans over their heads with a 22 Fetch wolf pup has become a leading - Guide Dogs hosts fi rst-ever force in wolf rescue and rehab. 8 Time for a reunion - Dinner & Auction for Humane Walk in the Art Society for SW Wash. 7 Luv-A-Bull Grab the guide and head - Fall fun with CAT - OHS hosts 9th annual Telethon for It began with a dream dog. -

44-77 (Katsottavissa Disney+ -Palvelussa 3.9 Menessä) ELOKUVAT JA SPESIAALIT 1

SISÄLLYS ELOKUVAT JA SPESIAALIT: 1- 43 SARJAT: 44-77 (Katsottavissa Disney+ -palvelussa 3.9 menessä) ELOKUVAT JA SPESIAALIT 10 Things I Hate About You 101 Dalmatians 101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure 102 Dalmatians 12 Dates of Christmas 12 Rounds 127 Hours 13th Warrior, The 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea 22 vs Earth 25th Hour 42 to 1 700 Sharks 9 to 5 9/11 Firehouse 9/11 Rescue Cops Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter Absent-Minded Professor, The Absolutely Fabulous: The Movie Adventures in Babysitting Adventures in Babysitting Adventures of Andre & Wally B., The Adventures of Bullwhip Griffin, The Adventures of Huck Finn, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, The African Cats African Lion, The Air Force One Air Mater Air Up There, The Aladdin Aladdin and the King of Thieves Alamo, The Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day Alice in Wonderland Alice Through the Looking Glass Alien Alien Resurrection Alien VS. Predator Alien: Covenant Alien3 Aliens Aliens of the Deep Aliens VS. Predator - Requiem All About Steve All in a Nutshell Alley Cats Strike Almost Angels Amelia American Eid America's Greatest Animals America's Heart & Soul Amy Anastasia Anatomy of a Dewback Anna and the King Annapolis Annie Another Earth Ant-Man Ant-Man and the Wasp Antwone Fisher Anywhere but Here Apollo: Missions to the Moon Apple Dumpling Gang Rides Again, The Apple Dumpling Gang, The Aquamarine Area 51: The Cia's Secret Arendelle Castle Yule Log 2.0 Aristocats, The Art of Getting By, The Art of Racing in the Rain, The Art of Skiing, -

Disney Plus Content List

Loremipsumdolor EverythingcomingtoDisney+intheUKonMarch24 sitamet Content list is correct at the time of issue. DISNEY (MOVIES) 101 Dalmatians (1996) 101 Dalmatians Ii: Patch's London Adventure 102 Dalmatians 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea Absent-Minded Professor, The Adventures Of Bullwhip Griffin, The Adventures Of Huck Finn, The Adventures Of Ichabod And Mr. Toad, The African Cats African Lion, The Aladdin (1992) Aladdin (2019) Aladdin And The King Of Thieves Alexander And The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day Alice In Wonderland (1951) Alice In Wonderland (2010) Alice Through The Looking Glass Alley Cats Strike (Disney Channel) America's Heart & Soul Amy Annie (1999) Apple Dumpling Gang Rides Again, The Apple Dumpling Gang, The Aristocats, The Atlantis: Milo's Return Atlantis: The Lost Empire Babes In Toyland Bambi Bambi Ii Bears Bears And I, The Beauty And The Beast (1991) Beauty And The Beast (2017) Beauty And The Beast-The Enchanted Christmas Bedknobs And Broomsticks Bedtime Stories Belle's Magical World (1998) Benji The Hunted Beverly Hills Chihuahua Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 Beverly Hills Chihuahua 3: Viva La Fiesta! Big Green, The Big Hero 6 Biscuit Eater, The Black Cauldron, The Black Hole, The (1979) Content list is correct at the time of issue. Blackbeard's Ghost Blank Check Bolt Born In China Boys, The: The Sherman Brothers' Story Brink! (Disney Channel) Brother Bear Brother Bear 2 Buffalo Dreams (Disney Channel) Cadet Kelly (Disney Channel) Can Of Worms (Disney Channel) Candleshoe Casebusters Castaway Cowboy, The -

D352d4ba73b67744a33302f591

Content list is correct at the time of issue DISNEY (MOVIES) 101 Dalmatians (1996) 101 Dalmatians Ii: Patch's London Adventure 102 Dalmatians 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea Absent-Minded Professor, The Adventures Of Bullwhip Griffin, The Adventures Of Huck Finn, The Adventures Of Ichabod And Mr. Toad, The African Cats African Lion, The Aladdin (1992) Aladdin (2019) Aladdin And The King Of Thieves Alexander And The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day Alice In Wonderland (1951) Alice In Wonderland (2010) Alice Through The Looking Glass Alley Cats Strike (Disney Channel) Almost Angels America's Heart & Soul Amy Annie (1999) Apple Dumpling Gang Rides Again, The Apple Dumpling Gang, The Aristocats, The Artemis Fowl Atlantis: Milo's Return Atlantis: The Lost Empire Babes In Toyland Bambi Bambi Ii Bears Bears And I, The Beauty And The Beast (1991) Beauty And The Beast (2017) Beauty And The Beast-The Enchanted Christmas Bedknobs And Broomsticks (Not In Luxembourg) Bedtime Stories Belle's Magical World (1998) Benji The Hunted Beverly Hills Chihuahua Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 Beverly Hills Chihuahua 3: Viva La Fiesta! Big Green, The Big Hero 6 Biscuit Eater, The Black Cauldron, The Content list is correct at the time of issue Black Hole, The (1979) Blackbeard's Ghost Blank Check Bolt Born In China Boy Who Talked To Badgers, The Boys, The: The Sherman Brothers' Story Bride Of Boogedy Brink! (Disney Channel) Brother Bear Brother Bear 2 Buffalo Dreams (Disney Channel) Cadet Kelly (Disney Channel) Can Of Worms (Disney Channel) Candleshoe Casebusters -

Wave 1 December 4, 2001 - 150,000 Tins Produced

Wave 1 December 4, 2001 - 150,000 tins produced Mickey Mouse Davy Crockett: in Living Color Silly Symphonies Disneyland USA The Complete (Volume 1) Buy Buy Televised Series Buy Review Review Buy Review Review Celebrate Mickey Mouse's This groundbreaking series Celebrating Walt Disney's Experience the hit television career in color cartoons of 31 uncensored cartoons, pioneering efforts in the show that became a national with 26 original shorts released between 1929 and medium of television, sensation and made released between 1935 and 1939, includes six Academy DISNEYLAND USA features coonskin caps a staple for a 1938 -- a timeless Award(R) winners and four vintage episodes of generation of American collection chronicling provides an astonishing Walt's beloved prime-time youngsters. With a rifle Mickey's first steps out of look inside the evolution of program. Take a wonderful named Old Betsy, Davy the world of black and animation. Each boasting a look back at the origins of Crockett fought for justice white, ushering in a new unique cast of characters, the park, beginning with with his own brand of era of animation. This these musical shorts served the very first episode of the homespun ingenuity. Enjoy classic uncensored as Walt Disney's proving DISNEYLAND TV series, as every episode of the popular compilation includes a wide ground for emerging Walt Disney leads a tour of Disney television series, array of special features, technology, new musical the studio and lifts the presented as originally including an inside look at styles, and experimental curtain on a model of the broadcast, complete with the creation of selected forms.