Defining the Museum of the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dxseeeb Syeceb Suquamish News

dxseEeb syeceb Suquamish News VOLUME 15 JUNE 2015 NO. 6 Reaching Milestones In this issue... Suquamish celebrates opening of new hotel tower and seafood plant Seafoods Opening pg. 3 CKA Mentors pg. 4 Renewal Pow Wow pg. 8 2 | June 2015 Suquamish News suquamish.org Community Calendar Featured Artist Demonstration Museum Movie Night the Veterans Center Office at (360) 626- contact Brenda George at brendageorge@ June 5 6pm June 25 6pm 1080. The Veterans Center is also open clearwatercasino.com. See first-hand how featured artist Jeffrey Join the museum staff for a double feature every Monday 9am-3pm for Veteran visit- Suquamish Tribal Veregge uses Salish formline designs in his event! Clearwater with filmmaker Tracy ing and Thursdays for service officer work Gaming Commission Meetings works, and the techniques he uses to merge Rector from Longhouse Media Produc- 9am-3pm. June 4 & 8 10am two disciplines during a demonstration. tions. A nonfiction film about the health The Suquamish Tribal Gaming Commis- For more information contact the Suqua- of the Puget Sound and the unique rela- Suquamish Elders Council Meeting sion holds regular meetings every other mish Museum at (360) 394-8499. tionship of the tribal people to the water. June 4 Noon Then Ocean Frontiers by filmmaker Karen The Suquamish Tribal Elders Council Thursday throughout the year. Meetings nd Museum 32 Anniversary Party Anspacker Meyer. An inspiring voyage to meets the first Thursday of every month in generally begin at 9am, at the Suquamish June 7 3:30pm coral reefs, seaports and watersheds across the Elders Dining Room at noon. -

Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation As a National Heritage Area

Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation as a National Heritage Area WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation as a National Heritage Area WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION APRIL 2010 The National Maritime Heritage Area feasibility study was guided by the work of a steering committee assembled by the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. Steering committee members included: • Dick Thompson (Chair), Principal, Thompson Consulting • Allyson Brooks, Ph.D., Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation • Chris Endresen, Office of Maria Cantwell • Leonard Forsman, Chair, Suquamish Tribe • Chuck Fowler, President, Pacific Northwest Maritime Heritage Council • Senator Karen Fraser, Thurston County • Patricia Lantz, Member, Washington State Heritage Center Trust Board of Trustees • Flo Lentz, King County 4Culture • Jennifer Meisner, Washington Trust for Historic Preservation • Lita Dawn Stanton, Gig Harbor Historic Preservation Coordinator Prepared for the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation by Parametrix Berk & Associates March , 2010 Washington State NATIONAL MARITIME HERITAGE AREA Feasibility Study Preface National Heritage Areas are special places recognized by Congress as having nationally important heritage resources. The request to designate an area as a National Heritage Area is locally initiated, -

The Creative Society Environmental Policymaking in California,1967

The Creative Society Environmental Policymaking in California,1967-1974 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert Denning Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Paula M. Baker, Advisor Dr. William R. Childs Dr. Mansel Blackford Copyright By Robert Denning 2011 Abstract California took the lead on environmental protection and regulation during Ronald Reagan‟s years as governor (1967-1974). Drawing on over a century of experience with conserving natural resources, environmentally friendly legislators and Governor Reagan enacted the strongest air and water pollution control programs in the nation, imposed stringent regulations on land use around threatened areas like Lake Tahoe and the San Francisco Bay, expanded the size and number of state parks, and required developers to take environmental considerations into account when planning new projects. This project explains why and how California became the national leader on environmental issues. It did so because of popular anger toward the environmental degradation that accompanied the state‟s rapid and uncontrolled expansion after World War II, the election of a governor and legislators who were willing to set environmental standards that went beyond what industry and business believed was technically feasible, and an activist citizenry that pursued new regulations through lawsuits and ballot measures when they believed the state government failed. The environment had a broad constituency in California during the Reagan years. Republicans, Democrats, students, bureaucrats, scientists, and many businessmen tackled the environmental problems that ii threatened the California way of life. -

Title Page: Arial Font

2016 IACC Conference - S24 Heritage Project 10/19/2016 Funding Heritage Capital Projects Funding? Does the project your organization is planning involve an historic property or support access to heritage? If so… it may be eligible for state HCP funding. WASHINGTON STATEExamples: HISTORICAL SOCIETY GRANT FUNDS FOR CAPITAL PROJECTS Historic Seattle PDA – Rehabilitation of THAT SUPPORT HERITAGE Washington Hall IACC CONFERENCE 2016 - OCTOBER 19, 2016 City Adapts and Reuses Old City Hall Park District Preserves Territorial History Tacoma Metropolitan Parks City of Bellingham - 1892 Old City Hall Preservation of the Granary at the Adaptively Reused as Whatcom Museum Fort Nisqually Living History Museum Multi-phased Window Restoration Project Point Defiance Park, Tacoma Suquamish Indian Nation’s Museum City Restores Station for Continued Use The Suquamish Indian Nation Suquamish Museum Seattle Dept. of Transportation King Street Station Restoration 1 2016 IACC Conference - S24 Heritage Project 10/19/2016 Funding Small Town Renovates its Town Hall City Builds Park in Recognition of History City of Tacoma – Chinese Reconciliation Park Town of Wilkeson – Town Hall Renovation Port Rehabilitates School and Gym Public Facilities District Builds New Museum Port of Chinook works with Friends of Chinook School – Chinook School Rehabilitation as a Community Center Richland Public Facilities District –The Reach City Preserves & Interprets Industrial History City Plans / Builds Interpretive Elements City of DuPont Dynamite Train City of Olympia – Budd Inlet Percival Landing Interpretive Elements 2 2016 IACC Conference - S24 Heritage Project 10/19/2016 Funding Port: Tourism as Economic Development Infrastructure That Creates Place Places and spaces – are social and community infrastructure Old and new, they connect us to our past, enhance our lives, and our communities. -

Suquamish Tribe 2017 Multi Hazard Mitigation Plan

Section 8 – Tsunami The Suquamish Tribe Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan 2017 The Suquamish Tribe Port Madison Indian Reservation November 5, 2017 Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan The Suquamish Tribe (This Page intentionally left blank) Multi- Hazard Mitigation Plan Page i Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan The Suquamish Tribe The Suquamish Tribe Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan Prepared for: The Suquamish Tribe, Port Madison Indian Reservation Funded by: The Suquamish Tribe & Federal Emergency Management Agency Pre-Disaster Mitigation Competitive Grant Program Project #: PDMC-10-WAIT-2013-001/Suquamish Tribe/Hazard Mitigation Plan Agreement #: EMS-2014-PC-0002 Prepared by: The Suquamish Office of Emergency Management Cherrie May, Emergency Management Coordinator Consultants: Eric Quitslund, Project Consultant Aaron Quitslund, Project Consultant Editor: Sandra Senter, Planning Committee Community Representative October, 2017 Multi- Hazard Mitigation Plan Page ii Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan The Suquamish Tribe (This Page intentionally left blank) Multi- Hazard Mitigation Plan Page iii Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan The Suquamish Tribe Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... iv Table of Tables ............................................................................................................................ viii Table of Maps ............................................................................................................................... -

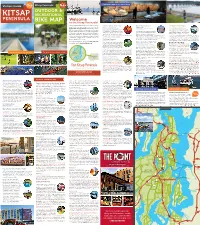

VKP Visitorguide-24X27-Side1.Pdf

FREE FREE MAP Kitsap Peninsula MAP DESTINATIONS & ATTRACTIONS Visitors Guide INSIDE INSIDE Enjoy a variety of activities and attractions like a tour of the Suquamish Museum, located near the Chief Seattle grave site, that tell the story of local Native Americans Welcome and their contribution to the region’s history and culture. to the Kitsap Peninsula! The beautiful Kitsap Peninsula is located directly across Gardens, Galleries & Museums Naval & Military History Getting Around the Region from Seattle offering visitors easy access to the www.VisitKitsap.com/gardens & Memorials www.VisitKitsap.com/transportation Natural Side of Puget Sound. Hop aboard a famous www.VisitKitsap.com/arts-and-culture visitkitsap.com/military-historic-sites- www.VisitKitsap.com/plan-your-event www.VisitKitsap.com/international-visitors WA State Ferry or travel across the impressive Tacaoma Visitors will find many places and events that veterans-memorials The Kitsap Peninsula is conveniently located Narrows Bridge and in minutes you will be enjoying miles offer insights about the region’s rich and diverse There are many historic sites, memorials and directly across from Seattle and Tacoma and a short of shoreline, wide-open spaces and fresh air. Explore history, culture, arts and love of the natural museums that pay respect to Kitsap’s remarkable distance from the Seattle-Tacoma International waterfront communities lined with shops, art galleries, environment. You’ll find a few locations listed in Naval, military and maritime history. Some sites the City & Community section in this guide and many more choices date back to the Spanish-American War. Others honor fallen soldiers Airport. One of the most scenic ways to travel to the Kitsap Peninsula eateries and attractions. -

AVAILABLE FROMCAUSE Exchange Library, 737 Twenty-Ninthstreet, Boulder, CO 80303

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 231 274 HE 016 260 TITLE The Information Resource: AManagement Challenge. Proceedings of the CAUSE National Conference(Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, November30-December 3, 1982). INSTITUTION CAUSE, Boulder, Colo. PUB DATE Dec 83 NOTE 516p. AVAILABLE FROMCAUSE Exchange Library, 737 Twenty-NinthStreet, Boulder, CO 80303. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings (021)-- Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC21 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College Administration; Computer Literacy;*Computer Oriented Programs; Computer Programs; Databases; Higher Education; Management Development;*Management Information Systems; *Microcomputers;*Program Administration; *Small Colleges ABSTRACT Proceedings of the 1982 CAUSE national conferenceon information resources for collegemanagement are presented. The 41 presentations cover five subject tracks:issues in higher education, managing the information systemsresource, technology and techniques, small college information systems, amd innovativeapplications. In addition, presentations of 10 vendors,a current issues forum concerning the role of administrative computing incollege-level computer literacy, an overview of CAUSE, anda keynote address are included. Some of the papers and authorsinclude the following: "Preparing Administrators for Automated InformationTechnologies" (Michael M. Byrne and Stanley Kardonsky);"Overview of Campus Computing Strategies" (Carolyn P. Landis); "LegalProtection for Software" (Jon Mosser and Maureen Murphy); "ProjectManagement:" The Key to'Effective -

Décoloniser La Muséologie Descolonizando La Museología

Decolonising Museology Décoloniser la Muséologie Descolonizando la Museología 2 The Decolonisation of Museology: Museums, Mixing, and Myths of Origin La Décolonisation de la Muséologie : Musées, Métissages et Mythes d’Origine La Descolonización de la Museología: Museos, Mestizajes y Mitos de Origen Editors Yves Bergeron, Michèle Rivet 1 Decolonising Museology Décoloniser la Muséologie Descolonizando la Museología Series Editor / Éditeur de la série / Editor de la Serie: Bruno Brulon Soares 1. A Experiência Museal: Museus, Ação Comunitária e Descolonização La Experiencia Museística: Museos, Acción Comunitaria y Descolonización The Museum Experience: Museums, Community Action and Decolonisation 2. The Decolonisation of Museology: Museums, Mixing, and Myths of Origin La Décolonisation de la Muséologie : Musées, Métissages et Mythes d’Origine La Descolonización de la Museología: Museos, Mestizajes y Mitos de Origen International Committee for Museology – ICOFOM Comité International pour la Muséologie – ICOFOM Comité Internacional para la Museología – ICOFOM Editors / Éditeurs / Editores: Yves Bergeron & Michèle Rivet Editorial Committee / Comité Éditorial / Comité Editorial Marion Bertin, Luciana Menezes de Carvalho President of ICOFOM / Président d’ICOFOM /Presidente del ICOFOM Bruno Brulon Soares Academic committee / Comité scientifique / Comité científico Karen Elizabeth Brown, Bruno Brulon Soares, Anna Leshchenko, Daniel Sch- mitt, Marion Bertin, Lynn Maranda, Yves Bergeron, Yun Shun Susie Chung, Elizabeth Weiser, Supreo Chanda, Luciana -

Persã¶Nlichkeit Der Gesellschaft Personen Liste

Persönlichkeit Der Gesellschaft Personen Liste Carmen Ordóñez https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/carmen-ord%C3%B3%C3%B1ez-4895658 Michèle Renouf https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/mich%C3%A8le-renouf-458339 Nayla Moawad https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/nayla-moawad-1395651 Charles Swann https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/charles-swann-2960274 Odette https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/odette-3349167 Mona von Bismarck https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/mona-von-bismarck-6897746 Paul Moss https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/paul-moss-7152631 Pauline Karpidas https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/pauline-karpidas-7155044 Uma Padmanabhan https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/uma-padmanabhan-7881023 Ardeshir Cowasjee https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/ardeshir-cowasjee-146291 Blanchette Ferry Rockefeller https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/blanchette-ferry-rockefeller-4924916 Ava Lord https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/ava-lord-2873226 Emily Gilmore https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/emily-gilmore-1153186 Tongsun Park https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/tongsun-park-7821144 Fulco di Verdura https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/fulco-di-verdura-2602710 Wafaa Sleiman https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/wafaa-sleiman-674366 Kojo Tovalou Houénou https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/kojo-tovalou-hou%C3%A9nou-6426501 Jacques de Bascher https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/jacques-de-bascher-30332144 Hans https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/hans-16251007 Linda Lee Thomas https://de.listvote.com/lists/person/linda-lee-thomas-6551749 -

Maine Alumnus, Volume 23, Number 4, January 1942

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine University of Maine Alumni Magazines University of Maine Publications 1-1942 Maine Alumnus, Volume 23, Number 4, January 1942 General Alumni Association, University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation General Alumni Association, University of Maine, "Maine Alumnus, Volume 23, Number 4, January 1942" (1942). University of Maine Alumni Magazines. 347. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines/347 This publication is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Maine Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JANUARY, 1942 The UNIVERSITY and NATIONAL DEFENSE This year, as every year, the University of Maine stands for service to the State and the Nation. But this year the University faces a need for service beyond that expected in ordinary times Your University through its stu dents, its faculty, and its facilities is contributing to National Defense in whatever ways it can while still adhering to its primary principle of providing sound educational opportunities. TRAINING for PRODUCTION ON the campus of the University and in eight cities and towns in the State the University is offering men and women special training to increase their value in the national war effort -

Calvin Klein, Inc

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. https://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA1141493 Filing date: 06/21/2021 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following parties oppose registration of the indicated application. Opposers Information Name Calvin Klein, Inc. Entity Corporation Citizenship New York Address 205 WEST 39TH STREET NEW YORK, NY 10018 UNITED STATES Name Calvin Klein Trademark Trust Entity Business Trust Citizenship Delaware Address 205 WEST 39TH STREET NEW YORK, NY 10018 UNITED STATES Attorney informa- MARC P. MISTHAL tion GOTTLIEB, RACKMAN & REISMAN, P.C. 270 MADISON AVENUE, 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10016 UNITED STATES Primary Email: [email protected] Secondary Email(s): [email protected] 2126843900 Docket Number 325/311 Applicant Information Application No. 90375613 Publication date 06/01/2021 Opposition Filing 06/21/2021 Opposition Peri- 07/01/2021 Date od Ends Applicant Hangzhou Xiaomu Dress Co., Ltd ROOM 1308, 13TH FLOOR, NO.288 JIANGUO SOUTH ROAD, SHANGCHENG DISTRICT, HANGZHOU ,ZHEJIANG, 310009 CHINA Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 025. First Use: 2020/11/10 First Use In Commerce: 2020/11/10 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Bonnets; Brassieres; Coats; Gloves; Over- coats; Shirts; Shoes; Sleepwear; Slippers; Sneakers; Socks; Sweaters; Tee-shirts; Trousers; Under- pants; Bathing suits; Clothing layettes; Men's suits, women's suits; Mufflers as neck scarves; Sports jerseys Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act Section 2(d) No use of mark in commerce before application Trademark Act Sections 1(a) and (c) or amendment to allege use was filed Dilution by blurring Trademark Act Sections 2 and 43(c) Dilution by tarnishment Trademark Act Sections 2 and 43(c) Fraud on the USPTO In re Bose Corp., 580 F.3d 1240, 91 USPQ2d 1938 (Fed. -

Décoloniser La Muséologie Descolonizando La Museología

Decolonising Museology Décoloniser la Muséologie Descolonizando la Museología 2 The Decolonisation of Museology: Museums, Mixing, and Myths of Origin La Décolonisation de la Muséologie : Musées, Métissages et Mythes d’Origine La Descolonización de la Museología: Museos, Mestizajes y Mitos de Origen Editors Yves Bergeron, Michèle Rivet 1 Decolonising Museology Décoloniser la Muséologie Descolonizando la Museología Series Editor / Éditeur de la série / Editor de la Serie: Bruno Brulon Soares 1. A Experiência Museal: Museus, Ação Comunitária e Descolonização La Experiencia Museística: Museos, Acción Comunitaria y Descolonización The Museum Experience: Museums, Community Action and Decolonisation 2. The Decolonisation of Museology: Museums, Mixing, and Myths of Origin La Décolonisation de la Muséologie : Musées, Métissages et Mythes d’Origine La Descolonización de la Museología: Museos, Mestizajes y Mitos de Origen International Committee for Museology – ICOFOM Comité International pour la Muséologie – ICOFOM Comité Internacional para la Museología – ICOFOM Editors / Éditeurs / Editores: Yves Bergeron & Michèle Rivet Editorial Committee / Comité Éditorial / Comité Editorial Marion Bertin, Luciana Menezes de Carvalho President of ICOFOM / Président d’ICOFOM /Presidente del ICOFOM Bruno Brulon Soares Academic committee / Comité scientifique / Comité científico Karen Elizabeth Brown, Bruno Brulon Soares, Anna Leshchenko, Daniel Sch- mitt, Marion Bertin, Lynn Maranda, Yves Bergeron, Yun Shun Susie Chung, Elizabeth Weiser, Supreo Chanda, Luciana