Critical Approaches to Fieldwork

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postclassic Aztec Figurines and Domestic Ritual

Copyright by Maribel Rodriguez 2010 The Thesis Committee for Maribel Rodriguez Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Postclassic Aztec Figurines and Domestic Ritual APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Julia Guernsey David Stuart Postclassic Aztec Figurines and Domestic Ritual by Maribel Rodriguez, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2010 Dedication Esto esta dedicado en especial para mi familia. Acknowledgements There are my academicians and friends I would like to extend my sincere gratitude. This research began thanks to Steve Bourget who encouraged and listened to my initial ideas and early stages of brainstorming. To Mariah Wade and Enrique Rodriguez-Alegria I am grateful for all their help, advice, and direction to numerous vital resources. Aztec scholars Michael Smith, Jeffrey and Mary Parsons, Susan T. Evans, and Salvador Guilliem Arroyo who provided assistance in the initial process of my research and offered scholarly resources and material. A special thank you to my second reader David Stuart for agreeing to be part of this project. This research project was made possible from a generous contribution from the Art and Art History Department Traveling grant that allowed me the opportunity to travel and complete archival research at the National American Indian History Museum. I would also like to thank Fausto Reyes Zataray for proofreading multiple copies of this draft; Phana Phang for going above and beyond to assist and support in any way possible; and Lizbeth Rodriguez Dimas and Rosalia Rodriguez Dimas for their encouragement and never ending support. -

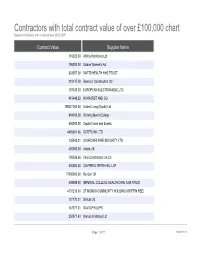

Contractors with Total Contract Value of Over £100,000 Chart Based on Contracts with a Value of Over 5000 GBP

Contractors with total contract value of over £100,000 chart Based on Contracts with a value of over 5000 GBP Contract Value Supplier Name 116325.00 Affinity Workforce Ltd 796000.00 Solace Women's Aid 323557.00 BARTS HEALTH NHS TRUST 210147.00 Boxmoor Construction Ltd 107420.30 EUROPEAN ELECTRONIQUE LTD 415448.22 HAYHURST AND CO 198221000.00 United Living (South) Ltd 894000.00 Working Men's College 450000.00 Capita Travel and Events 4405561.66 CATERLINK LTD 135545.21 CHURCHES FIRE SECURITY LTD 400000.00 Artelia UK 105036.66 Vinci Construction Uk Ltd 500000.00 CAMPBELL REITH HILL LLP 17000000.00 Re-Gen UK 408098.00 IMPERIAL COLLEGE HEALTHCARE NHS TRUST 4707213.00 ST MUNGO COMMUNITY HOUSING (GRIFFIN HSE) 131176.21 Softcat Ltd 147371.31 DAVID PHILLIPS 250971.43 Marcus & Marcus Ltd Page 1 of 22 10/02/2021 Contractors with total contract value of over £100,000 chart Based on Contracts with a value of over 5000 GBP 136044.00 CENTRAL & CECIL 198667.55 GODWIN & CROWNDALE TMC LTD 288142.90 PRICEWATERHOUSECOOPERS 494918.96 APEX HOUSING SOLUTIONS 425000.00 Rick Mather Architects LLP 148855.40 Alderwood LLA Ltd - Irchester 2 821312.26 Falcon Structural Repairs 1169203.00 Ark Build PLC 103675.37 MANOR HOSTELS (LONDON) LTD 319608347.72 VEOLIA ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES (UK) PLC 299532.76 CASTLEHAVEN COMMUNITY ASSOC. 207757.50 PERSONALISATION SUPPORT IN CAMDEN 12000000.00 AD Construction Group 678874.77 St Johns Wood - Lifestyle Care (2011) PLC 424893.63 INSIGHT DIRECT (UK) LTD 150366.19 HOLLY LODGE ESTATE COMMITTEE 114136.63 SPECIALIST COMPUTER CENTRES 943735.13 Mihomecare 4800000.00 Turner & Townsend Project Management Ltd 140000000.00 Volkerhighways 233048.00 KPMG 1150000.00 LONDON DIOCESAN BOARD FOR SCHOOLS Page 2 of 22 10/02/2021 Contractors with total contract value of over £100,000 chart Based on Contracts with a value of over 5000 GBP 302480.00 DAISY DATA CENTRE SOLUTIONS LTD 30000000.00 Eurovia Infrastructure 140126.15 DAWSONRENTALS BUS & COACH LTD 261847.08 ST MARTIN OF TOURS HOUSING ASSOC. -

Gerhard Bersu

Gerhard Bersu Jauer (Silésia), 26 de setembro de 1889; Magdebourgo, 19 de novembro de 1964 Gerhard Bersu (1889-1964) foi um dos arqueólogos que mais marcou a Arqueologia europeia durante e após as duas guerras mundiais. Natural de Jauer, Silésia (Alemanha), Gerhard Bersu desenvolveu intensa actividade arqueológica, inicialmente nas escavações dirigidas por Carl Schuchardt em Romerschanz (Potsdam, 1907) posteriormente em Cucuteni (Roménia) sob direcção de Hubert Schmidt. Participa na Primeira Guerra Mundial na frente Oeste como oficial responsável por Monumentos e Colecções tendo sido posteriormente nomeado para integrar a delegação alemã do armistício. Em 1924 inicia a sua ligação com o Instituto Arqueológico Alemão na Römisch Germanische Kommission (RGK), em Frankfurt-am-Main. Em 1928 é nomeado segundo director e em 1931 chega a primeiro director do RGK, tornando este instituto num centro prestigiado da Arqueologia europeia com o desenvolvimento de técnicas de escavação avançadas. Em 1935 o governo Nazi, sob influência de Reinhardt, invocando a origem judaica, afasta Bersu da direcção do RGK, e em 1937 é reformado compulsivamente, interrompendo um importante trabalho de investigação, formação avançada e de publicações. Sob ameaça do regime Nazi, em 1937 Bersu vai radicar-se no Reino Unido onde retoma a actividade arqueológica em Little Woodbury. Os trabalhos desenvolvidos com a Prehistoric Society forneceram importantes elementos para interpretação das fases pré-romanas. Com o início da Segunda Guerra Mundial, Bersu, tal como outros compatriotas alemães, é internado na Ilha de Man com a sua mulher, Maria. Inicialmente são separados em campos de detenção masculinos e femininos e depois juntam-se no campo para internos casados em Port St Mary. -

South East Maidstone Urban Extension Review of Cashflow Model and Viability

South East Maidstone Urban Extension Review of cashflow model and viability Prepared on behalf of Golding Homes 20 April 2012 Final DTZ 125 Old Broad Street London EC2N 2BQ PRIVATE & CONFIDENTIAL www.dtz.com Review of cashflow model and viability | Golding Homes Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Basis of Instruction 4 2 Golding Homes Financial Model Structure 5 2.1 Key Scheme Details 5 2.2 The Financial Model 6 3 Review of Revenue Assumptions 8 3.1 Revenue 8 3.1.1 Market Sale Housing 8 3.1.2 Affordable Housing 9 3.2 Future House Prices, Absorption and Sales Rates 10 3.2.1 Assumptions about Sales/ Build Out Rates 11 3.3 New Homes Bonus 12 3.4 Current Housing Land Supply 12 4 Review of Cost Assumptions 14 4.1 Cost 14 4.1.1 Unit Sizes 14 4.1.2 Build Costs 14 4.1.3 Code for Sustainable Homes 15 4.1.4 Cost Inflation 15 4.2 On Costs 16 4.3 Planning Contributions (CIL & s106) 17 4.4 Finance Rate 18 4.5 Infrastructure Costs 19 4.6 Land Value 20 4.7 Profit 20 5 Scenario Analysis 22 6 Summary 24 6.1 Delivery Structure 24 6.2 Financial Returns 24 Final 2 Review of cashflow model and viability | Golding Homes Status of Report and Limitations This report contains information which may be commercially sensitive if released. Circulation should be limited to appropriate individuals within Golding Homes. The contents of this report are confidential to Golding Homes in the context in which the report is supplied and DTZ expressly disclaims any responsibility towards third parties in respect of the whole or any part of its contents. -

Antoine Traisnel 435 S

ANTOINE TRAISNEL 435 S. State Street, 3132 Angell Hall, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 [email protected] ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Assistant Professor, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Departments of Comparative Literature and English Language and Literature (2015- present) Assistant Professor of Literary and Cultural Theory, Cornell University Department of Comparative Literature (2013-15) Term Assistant Professor (ATER), Université Paris 8 Department of English (2008-10) EDUCATION Ph.D., Comparative Literature, Brown University, 2013 Dissertation: “After the Animal: Predatory Pursuits in Antebellum America” Committee: Kevin McLaughlin (Chair), Barbara Herrnstein Smith, Timothy Bewes, Marc Redfield Cornell University Exchange Scholar, Department of English (2012-13) Adjunct Fellow in the Society for the Humanities, Yearlong focal theme “Risk” Ph.D., American Literature, Université Lille 3, 2009 Dissertation: “Nathaniel Hawthorne: L’allégorie critique, ou l’écriture de la crise” Supervised by Mathieu Duplay | Conferred with First-class honors Fulbright Fellow, Department of English, Brown University (2007-08) M.A., American Literature, Université Lille 3, 2005 Conferred with First-class honors Agrégation of English, Ecole Normale Supérieure de la rue d’Ulm, 2003-04 Awarded both Agrégation and CAPES of English (La Sorbonne), 2004 TEACHING AND RESEARCH FIELDS • Comparative Literature (English, • Literary and Critical Theory French, German) • Animal Studies and the Posthumanities • Nineteenth-Century American • Ecocriticism Literature ANTOINE TRAISNEL -

ANTHROPOLOGY 4FF3 DIGGING the CITY: the ARCHAEOLOGY of URBANISM Fall 2021

McMaster University, Department of Anthropology, ANTHROP 4FF3 ANTHROPOLOGY 4FF3 DIGGING THE CITY: THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF URBANISM Fall 2021 Instructor: Dr. Andy Roddick Email: [email protected] Live (Synchronous) Lecture: Office Hours: Held on zoom, set up via Wednesdays 8:30-11:20 am (Via Zoom) Calendly app on A2L Recording of these lectures posted by the end of day on Weds* Contents Course Description .......................................................................................................... 3 Course Objectives ........................................................................................................... 4 Required Materials and Texts ......................................................................................... 4 On-line Virtual Spaces ..................................................................................................... 4 Course Expectations and Requirements: ........................................................................ 5 Course Evaluation – Overview ........................................................................................ 5 Course Evaluation – Details ............................................................................................ 5 Weekly Course Schedule and Required Readings ......................................................... 7 Week 1 (January 13) Introductions .............................................................................. 7 Week 2 (January 20) Intellectual Foundations ............................................................ -

Changing Paradigms in Southeast Asian Archaeology

CHANGING PARADIGMS IN SOUTHEAST ASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY Joyce C. White Institute for Southeast Asian Archaeology and University of Pennsylvania Museum ABSTRACT (e.g., Tha Kae, Ban Mai Chaimongkol, Non Pa Wai, and In order for Southeast Asian archaeologists to effectively many other sites in central Thailand; but see White and engage with global archaeological discussions of the 21st Hamilton [in press] for progress on Ban Chiang). century, adoption of new paradigms is advocated. The But what I want to focus on here is our paradigmatic prevalent mid-twentieth century paradigm’s reliance on frameworks. Paradigms — that set of assumptions, con- essentialized frameworks and directional macro-views cepts, values, and practices that underlie an intellectual dis- should be replaced with a forward-facing, “emergent” cipline at particular points in time — matter. They matter paradigm and an emphasis on community-scale analyses partly because if we are parroting an out-of-date archaeo- in alignment with current trends in archaeological theory. logical agenda, we will miss out on three important things An example contrasting the early i&i pottery with early crucial for the vitality of the discipline of Southeast Asian copper-base metallurgy in Thailand illustrates how this archaeology in the long term. First is institutional support new perspective could approach prehistoric data. in terms of jobs. Second is resources. In both cases, appli- cants for jobs and grants need to be in tune with scholarly trends. Third, what interests me most in this paper, is our place in global archaeological discussions. Participating in INTRODUCTION global archaeological conversations, being a player in tune with the currents of the time, tends to assist in gaining in- When scholars reach the point in their careers that they are 1 stitutional support and resources. -

Theories of Ethnicity and the Dynamics of Ethnic Change in Multiethnic Societies Richard E

SPECIAL FEATURE: PERSPECTIVE PERSPECTIVE SPECIAL FEATURE: Theories of ethnicity and the dynamics of ethnic change in multiethnic societies Richard E. Blanton1 Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 Edited by Linda R. Manzanilla, Universidad Nacional Autonóma de México, Mexico, D.F., Mexico, and approved February 13, 2015 (received for review November 7, 2014) I modify Fredrik Barth’s approach, which sees ethnic group building as a signaling system, to place it within a framework that draws from collective action and costly signaling theories. From these perspectives, ethnic signaling, although representing a costly penalty to group members, is one effective form of communication that facilitates collective management of resources. I then identify three contexts in which the benefits of ethnic group building are likely to outweigh its signaling costs: in politically chaotic refuge and periphery zones; in the context of long-distance specialist trading groups; and within the territorial scope of failed states. I point to selected data from the Mughal and Aztec polities to illustrate how a combination of effective public goods management, in highly collective states, and the growth of highly integrated commercial economies will render ethnic group building superfluous. ethnicity | collective action | costly signaling Early in the 20th century, anthropologists tures or regions are understood to reflect to such evolution” (ref.8,p.108).Thekey turned to a focus on culture as a challenge to the distribution of a people and thus are problem, Geertz argues, is found in the fact thebiologicallyreductionistracethinkingof ethnically labeled, for example, as “Sumerian” that, within the boundaries of the new states, 19th century evolutionists. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

ARCHY 469 – Theory in Archaeology

ARCHY 469 – Theory in Archaeology Lecture: TTh 1:30 – 3:20pm, SMI 307 Instructor: Debora C. Trein Instructor’s office: DEN 133 Office Hours: F 11:30 – 1:30pm, or by appointment Email: [email protected] Source: unknown artist Course Description: How do we go from artifacts to statements about the lives of people in the past? How much of the past can we truly know, when most of the pertinent evidence has long since degraded, and when the people we aim to study are long dead? This course provides a broad survey of the major theoretical trends that have shaped anthropological archaeology over time. We will outline and examine some of the major publications, debates, and shifts in archaeological thought that have influenced the diverse ways in which we claim to know what we know about the past. In this course, we will explore the notion that the various intellectual approaches we employ to make statements about the past are influenced by the different perspectives we have of the relationship between the past and the present, the kinds of meaning we believe can be derived from the archaeological record, the questions we seek to answer, and the methods we use to retrieve (and prioritize) information. This course will start with a broad overview of the major periods of theoretical development in archaeology from the 1800s to the present, followed by discussions of how archaeologists tackle common archaeological questions through diverse theoretical lenses (and why sometimes they don’t tackle these questions at all). While the politics of archaeological practice will be 1 | Page touched upon throughout the course, we will devote the last quarter of the course to the repercussions of archaeological practice to present-day communities and stakeholders. -

A Latin American^, Sm

A LATIN AMERICAN^, ANTIQUITY VOLUME 10 NUMBER 2 JUNE 1999 SM Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.226, on 30 Sep 2021 at 15:47:26, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104566350001244XSOCIETY FOR AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY EDITORIAL STAFF OF LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY Editor. KATHARINA J. SCHREIBER, Department of Anthropology, University of California at Santa Barbara. CA 93106. Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Telephone (805) 893-4291 Editorial Assistant: CHRISTINA A. CONLEE. Department of Anthropology. University of California at Santa Barbara, CA 93106. Email: [email protected] Telephone (805) 893-5807 Fax: (805) 893-8707 Managing Editor. ELIZABETH FOXWELL. Society for American Archaeology, 900 Second Street, NE, Suite 12, Washington, DC 20002-3557 Email: [email protected] Telephone (202) 789-8200 Associate Editor for Reviews and Book Notes: MICHAEL E. SMITH, Department of Anthropology, Social Science 263, University at Albany (SUNY), Albany, NY, 12222. Email: [email protected] Telephone (518) 442-4709 Fax (518) 442-5710 BOARD OF EDITORS FOR LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY TOM D. DILLEHAY, Department of Anthropology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40504 ROBERT D. DRENNAN, Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh, 3H FQ, Pittsburgh. PA 15260 JOYCE MARCUS, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, University Museums Building, 1109 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1079 ELSA M. REDMOND, Department of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th St., New York, NY 10024 CHARLES STANISH, Department of Anthropology, Hershey Hall, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095 IRMHILD WUST, Universidade Federal de Goias, Av. -

A Circumpolar Reappraisal: the Legacy of Gutorm Gjessing (1906-1979)

A Circumpolar Reappraisal: The Legacy of Gutorm Gjessing (1906-1979) Proceedings of an International Conference held in Trondheim, Norway, 10th-12th October 2008, arranged by the Institute of Archaeology and Religious Studies, and the SAK department of the Museum of Natural History and Archaeology of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) Edited by Christer Westerdahl BAR International Series 2154 2010 Published by Archaeopress Publishers of British Archaeological Reports Gordon House 276 Ban bury Road Oxford 0X2 7ED England [email protected] www.archaeopress.com BAR S2154 A Circumpolar Reappraisal: The Legacy of Gutorm Gjessing (1906-1979). Proceedings of an International Conference held in Trondheim, Norway, 10th-12th October 2008, arranged by the Institute of Archaeology and Religious Studies, and the SAK department of the Museum of Natural History and Archaeology of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2010 ISBN 978 1 4073 0696 4 Front and back photos show motifs from Greenland and Spitsbergen. © C Westerdahl 1974, 1977 Printed in England by 4edge Ltd, Hockley All BAR titles are available from: Hadrian Books Ltd 122 Banbury Road Oxford 0X2 7BP England [email protected] www.hadrianbooks.co.uk The current BAR catalogue with details of all titles in print, prices and means of payment is available free from Hadrian Books or may be downloaded from www.archaeopress.com CHAPTER 7 ARCTIC CULTURES AND GLOBAL THEORY: HISTORICAL TRACKS ALONG THE CIRCUMPOLAR ROAD William W. Fitzhugh Arctic Studies Center, Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 2007J-J7072 fe// 202-(W-7&?7;./ai202-JJ7-2&&f; e-mail: fitzhugh@si.