An Ancient Surprise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

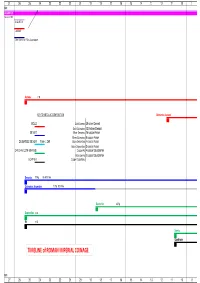

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

Abd-Hadad, Priest-King, Abila, , , , Abydos, , Actium, Battle

INDEX Abd-Hadad, priest-king, Akkaron/Ekron, , Abila, , , , Akko, Ake, , , , Abydos, , see also Ptolemaic-Ake Actium, battle, , Alexander III the Great, Macedonian Adaios, ruler of Kypsela, king, –, , , Adakhalamani, Nubian king, and Syria, –, –, , , , Adulis, , –, Aegean Sea, , , , , , –, and Egypt, , , –, , –, – empire of, , , , , , –, legacy of, – –, –, , , death, burial, – Aemilius Paullus, L., cult of, , , Aeropos, Ptolemaic commander, Alexander IV, , , Alexander I Balas, Seleukid king, Afrin, river, , , –, – Agathokleia, mistress of Ptolemy IV, and eastern policy, , and Demetrios II, Agathokles of Syracuse, , –, and Seventh Syrian War, –, , , Agathokles, son of Lysimachos, – death, , , , Alexander II Zabeinas, , , Agathokles, adviser of Ptolemy IV, –, , , –, Alexander Iannai, Judaean king, Aigai, Macedon, , – Ainos, Thrace, , , , Alexander, son of Krateros, , Aitolian League, Aitolians, , , Alexander, satrap of Persis, , , –, , , – Alexandria-by-Egypt, , , , , , , , , , , , , Aitos, son of Apollonios, , , –, , , Akhaian League, , , , , , , –, , , , , , , , , , , , , , Akhaios, son of Seleukos I, , , –, –, , – , , , , , , –, , , , Akhaios, son of Andromachos, , and Sixth Syrian War, –, adviser of Antiochos III, , – Alexandreia Troas, , conquers Asia Minor, – Alexandros, son of Andromachos, king, –, , , –, , , –, , , Alketas, , , Amanus, mountains, , –, index Amathos, Cyprus, and battle of Andros, , , Amathos, transjordan, , Amestris, wife of Lysimachos, , death, Ammonias, Egypt, -

Agorapicbk-15.Pdf

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 1s Prepared by Fred S. Kleiner Photographs by Eugene Vanderpool, Jr. Produced by The Meriden Gravure Company, Meriden, Connecticut Cover design: Coins of Gela, L. Farsuleius Mensor, and Probus Title page: Athena on a coin of Roman Athens Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1975 1. The Agora in the 5th century B.C. HAMMER - PUNCH ~ u= REVERSE DIE FLAN - - OBVERSE - DIE ANVIL - 2. Ancient method of minting coins. Designs were cut into two dies and hammered into a flan to produce a coin. THEATHENIAN AGORA has been more or less continuously inhabited from prehistoric times until the present day. During the American excava- tions over 75,000 coins have been found, dating from the 6th century B.c., when coins were first used in Attica, to the 20th century after Christ. These coins provide a record of the kind of money used in the Athenian market place throughout the ages. Much of this money is Athenian, but the far-flung commercial and political contacts of Athens brought all kinds of foreign currency into the area. Other Greek cities as well as the Romans, Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Turks have left their coins behind for the modern excavators to discover. Most of the coins found in the excavations were lost and never recovered-stamped into the earth floor of the Agora, or dropped in wells, drains, or cisterns. Consequently, almost all the Agora coins are small change bronze or copper pieces. -

Lecture 27 Sasanian Empire

4/12/2012 Lecture 27 Sasanian Empire HIST 213 Spring 2012 Sasanian Empire (224-651 CE) Successors of the Achaemenids 224 CE Ardashir I • a descendant of Sasan – gave his name to the new Sasanian dynasty, • defeated the Parthians • The Sasanians saw themselves as the successors of the Achaemenid Persians. 1 4/12/2012 Shapur I (r. 241–72 CE) • One of the most energetic and able Sasanian rulers • the central government was strengthened • the coinage was reformed • Zoroastrianism was made the state religion • The expansion of Sasanian power in the west brought conflict with Rome Shapur I the Conqueror • conquers Bactria and Kushan in east • led several campaigns against Rome in west Penetrating deep into Eastern-Roman territory • conquered Antiochia (253 or 256) Defeated the Roman emperors: • Gordian III (238–244) • Philip the Arab (244–249) • Valerian (253–260) – 259 Valerian taken into captivity after the Battle of Edessa – disgrace for the Romans • Shapur I celebrated his victory by carving the impressive rock reliefs in Naqsh-e Rostam. Rome defeated in battle Relief of Shapur I at Naqsh-e Rostam, showing the two defeated Roman Emperors, Valerian and Philip the Arab 2 4/12/2012 Terry Jones, Barbarians (BBC 2006) clip 1=9:00 to end clip 2 start - … • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t_WqUbp RChU&feature=related • http://www.youtube.com/watch?NR=1&featu re=endscreen&v=QxS6V3lc6vM Shapur I Religiously Tolerant Intensive development plans • founded many cities, some settled in part by Roman emigrants. – included Christians who could exercise their faith freely under Sasanian rule • Shapur I particularly favored Manichaeism – He protected Mani and sent many Manichaean missionaries abroad • Shapur I befriends Babylonian rabbi Shmuel – This friendship was advantageous for the Jewish community and gave them a respite from the oppressive laws enacted against them. -

The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1

Year 4: The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1 Duration 2 hours. Date: Planned by Katrina Gray for Two Temple Place, 2014 Main teaching Activities - Differentiation Plenary LO: To investigate who the Romans were and why they came Activities: Mixed Ability Groups. AFL: Who were the Romans? to Britain Cross curricular links: Geography, Numeracy, History Activity 1: AFL: Why did the Romans want to come to Britain? CT to introduce the topic of the Romans and elicit children’s prior Sort timeline flashcards into chronological order CT to refer back to the idea that one of the main reasons for knowledge: invasion was connected to wealth and money. Explain that Q Who were the Romans? After completion, discuss the events as a whole class to ensure over the next few lessons we shall be focusing on Roman Q What do you know about them already? that the children understand the vocabulary and events described money / coins. Q Where do they originate from? * Option to use CT to show children a map, children to locate Rome and Britain. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm or RESOURCES Explain that the Romans invaded Britain. http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/romans.html Q What does the word ‘invade’ mean? for further information about the key dates and events involved in Websites: the Roman invasion. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm To understand why they invaded Britain we must examine what http://www.sparklebox.co.uk/topic/past/roman-empire.html was happening in Britain before the invasion. -

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Coin quality, coin quantity, and coin value in early China and the Roman world Version 2.0 September 2010 Walter Scheidel Stanford University Abstract: In ancient China, early bronze ‘tool money’ came to be replaced by round bronze coins that were supplemented by uncoined gold and silver bullion, whereas in the Greco-Roman world, precious-metal coins dominated from the beginnings of coinage. Chinese currency is often interpreted in ‘nominalist’ terms, and although a ‘metallist’ perspective used be common among students of Greco-Roman coinage, putatively fiduciary elements of the Roman currency system are now receiving growing attention. I argue that both the intrinsic properties of coins and the volume of the money supply were the principal determinants of coin value and that fiduciary aspects must not be overrated. These principles apply regardless of whether precious-metal or base-metal currencies were dominant. © Walter Scheidel. [email protected] How was the valuation of ancient coins related to their quality and quantity? How did ancient economies respond to coin debasement and to sharp increases in the money supply relative to the number of goods and transactions? I argue that the same answer – that the result was a devaluation of the coinage in real terms, most commonly leading to price increases – applies to two ostensibly quite different monetary systems, those of early China and the Roman Empire. Coinage in Western and Eastern Eurasia In which ways did these systems differ? 1 In Western Eurasia coinage arose in the form of oblong and later round coins in the Greco-Lydian Aegean, made of electron and then mostly silver, perhaps as early as the late seventh century BCE. -

Pushing the Limit: an Analysis of the Women of the Severan Dynasty

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Greek and Roman Studies 4-24-2015 Pushing the Limit: An Analysis of the Women of the Severan Dynasty Colleen Melone Illinois Wesleyan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/grs_honproj Part of the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Melone, Colleen, "Pushing the Limit: An Analysis of the Women of the Severan Dynasty" (2015). Honors Projects. 5. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/grs_honproj/5 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Colleen Melone Pushing the Limit: An Analysis of the Women of the Severan Dynasty Abstract By applying Judith Butler’s theories of identity to the imperial women of the Severan dynasty in ancient Rome, this paper proves that while the Severan women had many identities, such as wife, mother, philosopher, or mourner, their imperial identity was most valued due to its ability to give them the freedom to step outside many aspects of their gender and to behave in ways which would customarily be deemed inappropriate. -

The Gallic Empire (260-274): Rome Breaks Apart

The Gallic Empire (260-274): Rome Breaks Apart Six Silver Coins Collection An empire fractures Roman chariots All coins in each set are protected in an archival capsule and beautifully displayed in a mahogany-like box. The box set is accompanied with a story card, certificate of authenticity, and a black gift box. By the middle of the third century, the Roman Empire began to show signs of collapse. A parade of emperors took the throne, mostly from the ranks of the military. Years of civil war and open revolt led to an erosion of territory. In the year 260, in a battle on the Eastern front, the emperor Valerian was taken prisoner by the hated Persians. He died in captivity, and his corpse was stuffed and hung on the wall of the palace of the Persian king. Valerian’s capture threw the already-fractured empire into complete disarray. His son and co-emperor, Gallienus, was unable to quell the unrest. Charismatic generals sought to consolidate their own power, but none was as powerful, or as ambitious, as Postumus. Born in an outpost of the Empire, of common stock, Postumus rose swiftly through the ranks, eventually commanding Roman forces “among the Celts”—a territory that included modern-day France, Belgium, Holland, and England. In the aftermath of Valerian’s abduction in 260, his soldiers proclaimed Postumus emperor. Thus was born the so-called Gallic Empire. After nine years of relative peace and prosperity, Postumus was murdered by his own troops, and the Gallic Empire, which had depended on the force of his personality, began to crumble. -

Civic Responses to the Rise and Fall of Sol Elagabal in the Roman Empire

EMPIRE OF THE SUN? CIVIC RESPONSES TO THE RISE AND FALL OF SOL ELAGABAL IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE Martijn Icks During its long and turbulent history, the city of Rome witnessed many changes in its religious institutions and traditions. For many centuries, these came to pass under the benevolent eye of Iupiter Optimus Maximus, the city‟s supreme deity since time immemorial. Not until the fourth century AD would Iupiter finally loose this position to the monotheistic, omnipotent God of Christianity. However, the power of the thunder god had been challenged before. The first deity who temporarily conquered his throne was Sol Invictus Elagabal, a local sun god from the Syrian town of Emesa. This unlikely usurper was the personal god of the emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, whose short-lived reign lasted from 218 to 222 AD, and who has been nicknamed Elagabalus for his affiliation with Elagabal. Even before his rise to power, Elagabalus served as Elagabal‟s high priest. The deity was worshipped in the form of a conical black stone, a so-called baitylos or “house of god”, which resided in a big temple in Emesa. Elagabalus, at that time a fourteen-year-old boy, performed ritual dances in honour of his god. By doing so, he drew the attention of Roman soldiers who were stationed near the town. They proclaimed the boy emperor under the false pretense that he was a bastard son of emperor Caracalla (211-217 AD). Elagabalus won sufficient military support, defeated the reigning emperor and thus gained the throne. He installed himself in Rome and took his god with him. -

Ptolemaic Foundations in Asia Minor and the Aegean As the Lagids’ Political Tool

ELECTRUM * Vol. 20 (2013): 57–76 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.13.004.1433 PTOLEMAIC FOUNDATIONS IN ASIA MINOR AND THE AEGEAN AS THE LAGIDS’ POLITICAL TOOL Tomasz Grabowski Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Kraków Abstract: The Ptolemaic colonisation in Asia Minor and the Aegean region was a signifi cant tool which served the politics of the dynasty that actively participated in the fi ght for hegemony over the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea basin. In order to specify the role which the settlements founded by the Lagids played in their politics, it is of considerable importance to establish as precise dating of the foundations as possible. It seems legitimate to acknowledge that Ptolemy II possessed a well-thought-out plan, which, apart from the purely strategic aspects of founding new settlements, was also heavily charged with the propaganda issues which were connected with the cult of Arsinoe II. Key words: Ptolemies, foundations, Asia Minor, Aegean. Settlement of new cities was a signifi cant tool used by the Hellenistic kings to achieve various goals: political and economic. The process of colonisation was begun by Alex- ander the Great, who settled several cities which were named Alexandrias after him. The process was successfully continued by the diadochs, and subsequently by the follow- ing rulers of the monarchies which emerged after the demise of Alexander’s state. The new settlements were established not only by the representatives of the most powerful dynasties: the Seleucids, the Ptolemies and the Antigonids, but also by the rulers of the smaller states. The kings of Pergamum of the Attalid dynasty were considerably active in this fi eld, but the rulers of Bithynia, Pontus and Cappadocia were also successful in this process.1 Very few regions of the time remained beyond the colonisation activity of the Hellenistic kings. -

The Roman Augustae: the Most Powerful Women Who Ever Lived a Collection of Six Silver Coins

The Roman Augustae: The Most Powerful Women Who Ever Lived A Collection of Six Silver Coins Frieze of Severan Dynasty All coins in each set are protected in an archival capsule and beautifully displayed in a mahogany-like box. The box set is accompanied with a story card, certificate of authenticity, and a black gift box. The best-known names of ancient Rome are invariably male, and in the 500 years between the reigns of Caesar Augustus and Justinian I, not a single woman held the Roman throne—not even during the chaotic Crisis of the Third Century, when new emperors claimed the throne every other year. This does not mean that women were not vital to the greatest empire the world has ever known. Indeed, much of the time, the real wielders of imperial might were the wives, sisters, and mothers of the emperors. Never was this more true than during the 193-235, when three women—the sisters Julia Maesa and Julia Domna, and Julia Maesa’s daughter Julia Avita Mamaea—secured the succession of their husbands, sons, and grandsons to the imperial throne, thus guaranteeing that they would remain in control. The dynasty is known in the history books as “the Severan,” for Julia Domna’s husband Septimius Severus, but it was the three Julias—and none of the men—who were really responsible for this relatively transition of power. These remarkable women, working in a patriarchal system that officially excluded them from assuming absolute power, nevertheless managed to have their way. Our story begins in Emesa, capital of the Roman client kingdom of Syria, in the year 187 CE. -

Histoire Des Collections Numismatiques Et Des Institutions Vouées À La Numismatique

HISTOIRE DES COLLECTIONS NUMISMATIQUES ET DES INSTITUTIONS VOUÉES À LA NUMISMATIQUE Numismatic Collections in Scotland Scotland is fortunate in possessing two major cabinets of international signifi- cance. In addition over 120 other institutions, from large civic museums to smaller provincial ones, hold collections of coins and medals of varying size and impor- tance. 1 The two main collections, the Hunterian held at the University of Glasgow, and the national collection, housed at the National Museums of Scotland in Edinburgh, nicely complement each other. The former, based on the renowned late 18th centu- ry cabinet of Dr. William Hunter, contains an outstanding collection of Greek and Roman coins as well as important groups of Anglo-Saxon, medieval and later English, and Scottish issues along with a superb holding of medals. The National Museums of Scotland house the largest and most comprehensive group of Scottish coins and medals extant. Each collection now numbers approximately 70,000 speci- mens. The public numismatic collections from the rest of Scotland, though perhaps not so well known, are now recorded to some extent due to a National Audit of the coun- try’s cultural heritage held by museums and galleries carried out by the Scottish Museums Council in 2001 on behalf of the Scottish Government. 2 Coins and Medals was one of 20 collections types included in the questionnaire, asking for location, size and breakdown into badges, banknotes, coins, medals, tokens, and other. Over 12 million objects made up what was termed the Distributed National Collection, of which 3.3% consisted of approximately 68,000 coins and medals in the National Museums concentrated in Edinburgh and 345,000 in the non-nationals throughout the rest of the country.