The Research History of Long Barrows in Russia and Estonia in the 5Th –10Th Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hassuna Samarra Halaf

arch 1600. archaeologies of the near east joukowsky institute for archaeology and the ancient world spring 2008 Emerging social complexities in Mesopotamia: the Chalcolithic in the Near East. February 20, 2008 Neolithic in the Near East: early sites of socialization “neolithic revolution”: domestication of wheat, barley, sheep, goat: early settled communities (ca 10,000 to 6000 BC) Mudding the world: Clay, mud and the technologies of everyday life in the prehistoric Near East • Pottery: associated with settled life: storage, serving, prestige pots, decorated and undecorated. • Figurines: objects of everyday, magical and cultic use. Ubiquitous for prehistoric societies especially. In clay and in stone. • Mud-brick as architectural material: Leads to more structured architectural constructions, perhaps more rectilinear spaces. • Tokens, hallow clay balls, tablets and early writing technologies: related to development o trade, tools of urban administration, increasing social complexity. • Architectural models: whose function is not quite obvious to us. Maybe apotropaic, maybe for sale purposes? “All objects of pottery… figments of potter’s will, fictions of his memory and imagination.” J. L. Myres 1923, quoted in Wengrow 1998: 783. What is culture in “culture history” (1920s-1960s) ? Archaeological culture = a bounded and binding ethnic/cultural unit within a defined geography and temporal/spatial “horizons”, uniformly and unambigously represented in the material culture, manifested by artifactual assemblage. pots=people? • “Do cultures actually -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Neolithic and chalcolithic cultures in Turkish Thrace Erdogu, Burcin How to cite: Erdogu, Burcin (2001) Neolithic and chalcolithic cultures in Turkish Thrace, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3994/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk NEOLITHIC AND CHALCOLITHIC CULTURES IN TURKISH THRACE Burcin Erdogu Thesis Submitted for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. University of Durham Department of Archaeology 2001 Burcin Erdogu PhD Thesis NeoHthic and ChalcoHthic Cultures in Turkish Thrace ABSTRACT The subject of this thesis are the NeoHthic and ChalcoHthic cultures in Turkish Thrace. Turkish Thrace acts as a land bridge between the Balkans and Anatolia. -

Bronze Age Tell Communities in Context: an Exploration Into Culture

Bronze Age Tell Kienlin This study challenges current modelling of Bronze Age tell communities in the Carpathian Basin in terms of the evolution of functionally-differentiated, hierarchical or ‘proto-urban’ society Communities in Context under the influence of Mediterranean palatial centres. It is argued that the narrative strategies employed in mainstream theorising of the ‘Bronze Age’ in terms of inevitable social ‘progress’ sets up an artificial dichotomy with earlier Neolithic groups. The result is a reductionist vision An exploration into culture, society, of the Bronze Age past which denies continuity evident in many aspects of life and reduces our understanding of European Bronze Age communities to some weak reflection of foreign-derived and the study of social types – be they notorious Hawaiian chiefdoms or Mycenaean palatial rule. In order to justify this view, this study looks broadly in two directions: temporal and spatial. First, it is asked European prehistory – Part 1 how Late Neolithic tell sites of the Carpathian Basin compare to Bronze Age ones, and if we are entitled to assume structural difference or rather ‘progress’ between both epochs. Second, it is examined if a Mediterranean ‘centre’ in any way can contribute to our understanding of Bronze Age tell communities on the ‘periphery’. It is argued that current Neo-Diffusionism has us essentialise from much richer and diverse evidence of past social and cultural realities. Tobias L. Kienlin Instead, archaeology is called on to contribute to an understanding of the historically specific expressions of the human condition and human agency, not to reduce past lives to abstract stages on the teleological ladder of social evolution. -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

Neolithic Farmers in Poland - a Study of Stable Isotopes in Human Bones and Teeth from Kichary Nowe in the South of Poland

Neolithic farmers in Poland - A study of stable isotopes in human bones and teeth from Kichary Nowe in the south of Poland Master thesis in archaeological science Archaeological Research Laboratory Stockholm University Supervisors: Kerstin Lidén and Gunilla Eriksson Author: Staffan Lundmark Cover photo: Mandible from the Kichary Nowe site, photo taken by the author Abstract: The diet of the Stone Age cultures is a strong indicator to the social group, thus farmers and hunters can be distinguished through their diet. There is well-preserved and well excavated Polish skeletal material available for such a study but the material has not previously been subject to stable isotopes analyses and therefore the questions of diets has not been answered. This study aims to contribute to the understanding of the cultures in the Kichary Nowe 2 area in the Lesser Poland district in southern Poland. Through analysis of the stable isotopes of Carbon, Nitrogen and Sulphur in the collagen of teeth and skeletal bones from the humans in the Kichary Nowe 2 grave-field and from bones from the fauna, coeval and from the same area, the study will establish whether there were any sharp changes of diets. The material from the grave-field comes from cultures with an established agricultural economy, where their cultural belonging has been anticipated from the burial context. The results from my study of stable isotopes from the bone material will be grouped by various parameters, culture, attribution to sex and age. The groups will then be compared to each other to investigate patterns within and between the groups. -

The Landscape Archaeology of Martin Down

The Landscape Archaeology of Martin Down Martin Down and the surrounding area contain a variety of well‐preserved archaeological remains, largely because the area has been unaffected by modern agriculture and development. This variety of site types and the quality of their preservation are relatively unusual in the largely arable landscapes of central southern England. Bokerley Dyke, Grim's Ditch, the short section of medieval park boundary bank and the two bowl barrows west of Grim's Ditch, form the focus of the Martin Down archaeological landscape and, as such, have been the subject of part excavations and a detailed survey by the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England. These investigations have provided much information about the nature and development of early land division, agriculture and settlement within this area during the later prehistoric and historic periods. See attached map for locations of key sites A ritual Neolithic Landscape….. Feature 1. The Dorset Cursus The Cursus dates from 3300 BCE which makes it contemporary with the earthen long barrows on Cranborne Chase: many of these are found near, on, or within the Cursus and since they are still in existence they help trace the Cursus' course in the modern landscape. The relationship between the Cursus and the alignment of these barrows suggests that they had a common ritual significance to the Neolithic people who spent an estimated 0.5 million worker‐hours in its construction. A cursus circa 6.25 miles (10 kilometres) long which runs roughly southwest‐northeast between Thickthorn Down and Martin Down. Narrow and roughly parallel‐sided, it follows a slightly sinuous course across the chalk downland, crossing a river and several valleys. -

THE Mckern “TAXONOMIC” SYSTEM and ARCHAEOLOGICAL CULTURE CLASSIFICATION in the MIDWESTERN UNITED STATES: a HISTORY and EVALUATION

Published in Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 3-9 (1996). Excepting some very minor revisions and McKern's quote describing the structure and detail of his classification this was the paper read at the IInd Indianapolis Archaeological Conference, Sheraton Meridian Hotel, November 15, 1986, organized by Neal L. Trubowitz. Since the reader of this article does not have the contributions of the other participants that describe the system it was thought advisable that it be included. The proceedings of this event were to be published as a commemorative volume of the first conference, but this never occurred. THE McKERN “TAXONOMIC” SYSTEM AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL CULTURE CLASSIFICATION IN THE MIDWESTERN UNITED STATES: A HISTORY AND EVALUATION By B. K. Swartz, Jr. from Selected Writings ABSTRACT In the first half of the 20th century three major archaeological culture unit classifications were formulated in the United States. The most curious one was the Midwestern "Taxonomic" System, a scheme that ignored time and space. Alton K. Fisher suggested to W. C. McKern in the late 1920's that the Linnean model of morphological classification, which was employed in biology at a time of pre-evolutionary thinking, might be adapted to archaeological culture classification (Fisher 1986). On the basis of this idea McKern conceived the Midwestern Taxonomic System and planned to present his concept in a paper at the Central Section of the American Anthropological Association at Ann Arbor, Michigan, in April 1932. Illness prevented him from making the presentation. The first public statement was before a small group of archaeologists at the time of an archaeological symposium, Illinois Academy of Science, May 1932 (Griffin 1943:327). -

Supplementary Information for Ancient Genomes from Present-Day France

Supplementary Information for Ancient genomes from present-day France unveil 7,000 years of its demographic history. Samantha Brunel, E. Andrew Bennett, Laurent Cardin, Damien Garraud, Hélène Barrand Emam, Alexandre Beylier, Bruno Boulestin, Fanny Chenal, Elsa Cieselski, Fabien Convertini, Bernard Dedet, Sophie Desenne, Jerôme Dubouloz, Henri Duday, Véronique Fabre, Eric Gailledrat, Muriel Gandelin, Yves Gleize, Sébastien Goepfert, Jean Guilaine, Lamys Hachem, Michael Ilett, François Lambach, Florent Maziere, Bertrand Perrin, Susanne Plouin, Estelle Pinard, Ivan Praud, Isabelle Richard, Vincent Riquier, Réjane Roure, Benoit Sendra, Corinne Thevenet, Sandrine Thiol, Elisabeth Vauquelin, Luc Vergnaud, Thierry Grange, Eva-Maria Geigl, Melanie Pruvost Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], Contents SI.1 Archaeological context ................................................................................................................. 4 SI.2 Ancient DNA laboratory work ................................................................................................... 20 SI.2.1 Cutting and grinding ............................................................................................................ 20 SI.2.2 DNA extraction .................................................................................................................... 21 SI.2.3 DNA purification ................................................................................................................. 22 SI.2.4 -

Prehistoric Hilltop Settlement in the West of Ireland Number 89 Summer

THE NEWSLETTERAST OF THE PREHISTORIC SOCIETY P Registered Office: University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31–34 Gordon Square, London WC1H 0PY http://www.prehistoricsociety.org/ Prehistoric hilltop settlement in the west of Ireland For two weeks during the summer of 2017, from the end footed roundhouses were recorded on the plateau, and further of July through the first half of August, an excavation was structures were identified in a survey undertaken by Margie carried out at three house sites on Knocknashee, Co. Sligo, Carty from NUI Galway during the early 2000s, bringing by a team from Queen’s University Belfast. Knocknashee the total to 42 roundhouses. is a visually impressive flat-topped limestone hill rising 261 m above the central Sligo countryside. Archaeologists However, neither of these two surveys was followed up by have long been drawn to the summit of Knocknashee excavation, and as the boom of development-driven archae- because of the presence of two large limestone cairns to the ology during the Celtic Tiger years has largely spared exposed north of the plateau, and aerial photographs taken by the hilltop locations, our archaeological knowledge not only of Cambridge University Committee for Aerial Photography Knocknashee, but also of prehistoric hilltop settlements in in the late 1960s also identified an undetermined number Ireland more widely remains relatively limited in comparison of prehistoric roundhouses on the summit. During survey to many other categories of site. This lack of knowledge work undertaken -

Russia and Siberia: the Beginning of the Penetration of Russian People Into Siberia, the Campaign of Ataman Yermak and It’S Consequences

The Aoyama Journal of International Politics, Economics and Communication, No. 106, May 2021 CCCCCCCCC Article CCCCCCCCC Russia and Siberia: The Beginning of the Penetration of Russian People into Siberia, the Campaign of Ataman Yermak and it’s Consequences Aleksandr A. Brodnikov* Petr E. Podalko** The penetration of the Russian people into Siberia probably began more than a thousand years ago. Old Russian chronicles mention that already in the 11th century, the northwestern part of Siberia, then known as Yugra1), was a “volost”2) of the Novgorod Land3). The Novgorod ush- * Associate Professor, Novosibirsk State University ** Professor, Aoyama Gakuin University 1) Initially, Yugra was the name of the territory between the mouth of the river Pechora and the Ural Mountains, where the Finno-Ugric tribes historically lived. Gradually, with the advancement of the Russian people to the East, this territorial name spread across the north of Western Siberia to the river Taz. Since 2003, Yugra has been part of the offi cial name of the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug: Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug—Yugra. 2) Volost—from the Old Russian “power, country, district”—means here the territo- rial-administrative unit of the aboriginal population with the most authoritative leader, the chief, from whom a certain amount of furs was collected. 3) Novgorod Land (literally “New City”) refers to a land, also known as “Gospodin (Lord) Veliky (Great) Novgorod”, or “Novgorod Republic”, with its administrative center in Veliky Novgorod, which had from the 10th century a tendency towards autonomy from Kiev, the capital of Ancient Kievan Rus. From the end of the 11th century, Novgorod de-facto became an independent city-state that subdued the entire north of Eastern Europe. -

The Long Barrows and Long Mounds of West Mendip

Proc. Univ. Bristol Spelaeol. Soc., 2008, 24 (3), 187-206 THE LONG BARROWS AND LONG MOUNDS OF WEST MENDIP by JODIE LEWIS ABSTRACT This article considers the evidence for Early Neolithic long barrow construction on the West Mendip plateau, Somerset. It highlights the difficulties in assigning long mounds a classification on surface evidence alone and discusses a range of earthworks which have been confused with long barrows. Eight possible long barrows are identified and their individual and group characteristics are explored and compared with national trends. Gaps in the local distribution of these monuments are assessed and it is suggested that areas of absence might have been occupied by woodland during the Neolithic. The relationship between long barrows and later round barrows is also considered. INTRODUCTION Long barrows are amongst the earliest monuments to have been built in the Neolithic period. In Southern Britain they take two forms: non-megalithic (or “earthen”) long barrows and megalithic barrows, mostly belonging to the Cotswold-Severn tradition. Despite these differences in architectural construction, the long mounds are of the same, early 4th millennium BC, date and had a similar purpose. The chambers of the long mounds were used for the deposition of the human dead and the monuments themselves appear to have acted as a focus for ritual activities and religious observations by the living. Some long barrows show evidence of fire lighting, feasting and deposition in the forecourts and ditches of the monuments, and alignment upon solstice events has also been noted. A local example of this can be observed at Stoney Littleton, near Bath, where the entrance and passage of this chambered long barrow are aligned upon the midwinter sunrise1. -

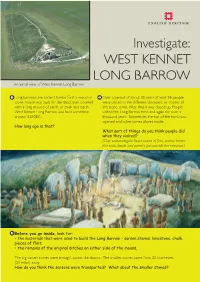

Investigate: WEST KENNET LONG BARROW an Aerial View of West Kennet Long Barrow

Investigate: WEST KENNET LONG BARROW An aerial view of West Kennet Long Barrow 1 Long barrows are ancient tombs. First a wood or 2 Over a period of about 30 years at least 36 people stone ‘house’ was built for the dead, then covered were placed in the different chambers or ‘rooms’ of with a long mound of earth, or chalk and earth. the stone tomb. After that it was closed up. People West Kennet Long Barrow was built sometime visited the Long Barrow time and again for over a around 3,650BC. thousand years. Sometimes the top of the tomb was opened and other bones placed inside. How long ago is that? What sort of things do you think people did when they visited? (Clue: archaeologists found traces of fires, animal bones, flint tools, beads and pottery just outside the entrance.) © Judith Dobie, English Heritage Graphics Team 3 Before you go inside, look for: • the materials that were used to build the Long Barrow – sarsen stones, limestone, chalk, pieces of flint; • the remains of the original ditches on either side of the mound. The big sarsen stones were brought across the downs. The smaller stones came from 32 kilometres (20 miles) away. How do you think the sarsens were transported? What about the smaller stones? 4 Draw your own sketch of West Kennet 5 Can you estimate the length and width of Long Barrow. the whole Long Barrow? length = width = N © Judith Dobie, English Heritage Graphics Team 6 You can see Silbury Hill from here. Would you have been able to see it when the Long Barrow was being built? (Clue: Silbury Hill was begun around 2400BC) 7 Find the huge sarsen stone in the burial chamber on the left.