Dead Silence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludhiana Rural

POLICE DEPARTMENT DISTT LUDHIANA RURAL LIST OF NRI PO U/S 82/83 CrPC SR. DISTT NAME & ADDRESS OF THE FIR NO , DATE , U/S & PS NAME OF THE FULL ADDRESS REMARKS IF NO NRI PO OF INDIA FOREIGN OF THE ANY COUNTRY FOREIGN COUNTRY 1. Ludhiana- Ranjit Singh s/o Bachan Singh 208/28.8.2002 u/s Canada Not available Recommended to Rural r/o Basrawan PS Raikot 420/406/420-B IPC PS continue the PO Jagraon proceeding 2. Ludhiana- Bhupinder Singh s/o Balwant 243/28.11.01 u/s 420/406 Canada Not available -do- Rural Singh r/o Kukkar Bazar Jagraon IPC PS Jagraon 3. Ludhiana- Harpreet Singh s/o Harnek 378/20.11.05 u/s 121- USA Not available -do- Rural Singh r/o Latala A/122/123 IPC PS Jagraon 4. Ludhiana- Jagjiwan Singh s/o Gulwant 13, 15.1.04 u/s 420/406 IPC England Not available -do- Rural Singh r/o Leehlan Megh Singh PS Sidhwan Bet PS Sidhwant Bet 5. Ludhiana- Sulinder Singh s/o Iqbal Singh 169, 12.7.05 u/s 420/121- Germany Not available Rural r/o Sowaddi Khurd PS Sidhwant A/122/123 IPC PS Sidhwan Bet Bet 6. Ludhiana- Kamaljit Kaur w/o Nirbhai 76, 4.12.92 U/S 302/506/34 Canada Not available Rural Singh r/o Umarpura PS Raikot IPC 25 A.Act PS Raikot 7. Ludhiana- Gurdev Singh s/o Sajjan Singh 81, 3.9.2K u/s Canada Not available Rural r/o Barmi PS Raikot 420/467/468/471 IPC PS Raikot 8. -

Application Employee of High Sr No

Application Employee of High Sr No. Seq No Rollno Applicant Full Name Father's Full Name Applicant Mother Name DOB (dd/MMM/yyyy) Domicile of State Category Sub_Category Email ID Gender Mobile Number Court Allahabad Is Present Score 1 1000125 2320015236 ANIL KUMAR SHIV CHARAN ARYA MAHADEVI 6/30/1990 Uttar Pradesh OBC Sports Person (S.P.)[email protected] Male 9911257770 No PRESENT 49 2 1000189 2320015700 VINEET AWASTHI RAM KISHOR AWASTHI URMILA AWASTHI 4/5/1983 Uttar Pradesh General NONE [email protected] 8423230100 No PRESENT 43 3 1000190 2110045263HEMANT KUMAR SHARMA GHANSHYAM SHARMA SHAKUNTALA DEVI 3/22/1988 Other than Uttar Pradesh General [email protected] 9001934082 No PRESENT 39 4 1000250 2130015960 SONAM TIWARI SHIV KUMAR TIWARI GEETA TIWARI 4/21/1991 Other than Uttar Pradesh General [email protected] Male 8573921039 No PRESENT 44 5 1000487 2360015013 RAJNEESH KUMAR RAJVEER SINGH VEERWATI DEVI 9/9/1989 Uttar Pradesh SC NONE [email protected] Male 9808520812 No PRESENT 41 6 1000488 2290015053 ASHU VERMA LATE JANARDAN LAL VERMA PADMAVATI VERMA 7/7/1992 Uttar Pradesh SC NONE [email protected] Male 9005724155 No PRESENT 36 7 1000721 2420015498 AZAJUL AFZAL MOHAMMAD SHAHID NISHAD NAZMA BEGUM 2/25/1985 Uttar Pradesh General NONE [email protected] 7275529796 No PRESENT 27 8 1000794 2250015148AMBIKA PRASAD MISHRA RAM NATH MISHRA NIRMALA DEVI 12/24/1991 Uttar Pradesh General NONE [email protected] Male 8130809970 No PRESENT 36 9 1001008 2320015652 SATYAM SHUKLA PREM PRAKASH -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Ludhiana, Part

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES-20 PUNJAB DISTRICT 'CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII - A & B VILLAGE &TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DISTRICT LUDHIANA Director of· Census Operations Punjab I I • G ~ :x: :x: ~.• Q - :r i I I@z@- ~ . -8. till .11:: I I ,~: : ,. 1l •., z ... , z . Q II) · 0 w ::t ; ~ ~ :5 ... ...J .... £ ::::> ~ , U , j:: .. « c.. tJ) ~ 0 w . ~ c.. t,! ' !!; I! 0 II) <> I « w .... ... 0 i3 z « ~ Vi at: 0 U .· [Il (J) W :x: ;::: U Z 0 « « « ii. 0- 0 c;: J: .., Z 0 ... u .~ « a ::::> u_ w t- 0 ;:: : : c.. 0 ... ~ U at: « ~ a ~ '0 x I- : :x: a: II) 0 c.. 0 .. U 0 c.. ... z ~ 0 Iii w ~ 8 « ... ...J :x: :x: « .. U ~~ i5~ ...J « : 0:: ;; 0- II) t: W => ~ C2 oct '"~ w 0- 5: :x: c:i Vi::: ;: 0:: 0 w I.!l .. Iii W I- ... W . ~ « at::x: ~ IJ) ~ i5 U w~ ~ w «z w ... .... ... s: «w> w<t t- <:l .w ~ &:3: :x: 0- 6 e at: ...J :X:z: 0 ulI) U ~ « ... I.!l Z «~ ::::> ";;: « « x <t w« z w. a A 0 z ~ ~ I.!lZ ZH'" « WI :x: .... Z t a0 0 w (l: ' 5: a::: «,.. ;j o .J W :3:x: [Il .... a::: ::::> « ;:: ~ c.. - _,O- Iii I.!l Iii a w « 0- > 0:":: 0 W W tS- [Il ~_ «(l: :x: z . Ul ii1 >s: ::::> .... c.. e, 0:: ui a: w <t. (i -z. « « a0 <[ w I :x: 0 --' m iii ::> :x: ...J « ~ 0- z l- < 0 ::::> 0:: UI t- e/) :g N ...J --' o. -

Nishaan – Blue Star-II-2018

II/2018 NAGAARA Recalling Operation ‘Bluestar’ of 1984 Who, What, How and Why The Dramatis Personae “A scar too deep” “De-classify” ! The Fifth Annual Conference on the Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib, jointly hosted by the Chardi Kalaa Foundation and the San Jose Gurdwara, took place on 19 August 2017 at San Jose in California, USA. One of the largest and arguably most beautiful gurdwaras in North America, the Gurdwara Sahib at San Jose was founded in San Jose, California, USA in 1985 by members of the then-rapidly growing Sikh community in the Santa Clara Valley Back Cover ContentsIssue II/2018 C Travails of Operation Bluestar for the 46 Editorial Sikh Soldier 2 HERE WE GO AGAIN: 34 Years after Operation Bluestar Lt Gen RS Sujlana Dr IJ Singh 49 Bluestar over Patiala 4 Khushwant Singh on Operation Bluestar Mallika Kaur “A Scar too deep” 22 Book Review 1984: Who, What, How and Why Jagmohan Singh 52 Recalling the attack on Muktsar Gurdwara Col (Dr) Dalvinder Singh Grewal 26 First Person Account KD Vasudeva recalls Operation Bluestar 55 “De-classify !” Knowing the extent of UK’s involvement in planning ‘Bluestar’ 58 Reformation of Sikh institutions? PPS Gill 9 Bluestar: the third ghallughara Pritam Singh 61 Closure ! The pain and politics of Bluestar 12 “Punjab was scorched 34 summers Jagtar Singh ago and… the burn still hurts” 34 Hamid Hussain, writes on Operation Bluestar 63 Resolution by The Sikh Forum Kanwar Sandhu and The Dramatis Personae Editorial Director Editorial Office II/2018 Dr IJ Singh D-43, Sujan Singh Park New Delhi 110 -

FOREWORD the Need to Prepare a Clear and Comprehensive Document

FOREWORD The need to prepare a clear and comprehensive document on the Punjab problem has been felt by the Sikh community for a very long time. With the release of this White Paper, the S.G.P.C. has fulfilled this long-felt need of the community. It takes cognisance of all aspects of the problem-historical, socio-economic, political and ideological. The approach of the Indian Government has been too partisan and negative to take into account a complete perspective of the multidimensional problem. The government White Paper focusses only on the law and order aspect, deliberately ignoring a careful examination of the issues and processes that have compounded the problem. The state, with its aggressive publicity organs, has often, tried to conceal the basic facts and withhold the genocide of the Sikhs conducted in Punjab in the name of restoring peace. Operation Black Out, conducted in full collaboration with the media, has often led to the circulation of one-sided versions of the problem, adding to the poignancy of the plight of the Sikhs. Record has to be put straight for people and posterity. But it requires volumes to make a full disclosure of the long history of betrayal, discrimination, political trickery, murky intrigues, phoney negotiations and repression which has led to blood and tears, trauma and torture for the Sikhs over the past five decades. Moreover, it is not possible to gather full information, without access to government records. This document has been prepared on the basis of available evidence to awaken the voices of all those who love justice to the understanding of the Sikh point of view. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1994 , 05/04/2021 Class 39

Trade Marks Journal No: 1994 , 05/04/2021 Class 39 3236639 14/04/2016 POONAM CHOUDHARY 8/276, MALVIYA NAGAR, JAIPUR, RAJ. POONAM CHOUDHARY INDIVIDUAL Address for service in India/Attorney address: MONIKA TAPARIA 183, Ganesh Vihar, Sirsi mod, sirsi road, Jaipur 302012 Used Since :01/04/2016 AHMEDABAD TRANSPORT, PACKAGING AND STORAGE OF GOODS, TRAVEL ARRANGEMENT, CAR RENTAL SERVICES INCLUDED IN CLASS 39. Subject to no separate claim over words except as shown in the form of representation. 4522 Trade Marks Journal No: 1994 , 05/04/2021 Class 39 NUMADIC 3714277 28/12/2017 NUMADIC LIMITED UK 10 John Street, London, United Kingdom, WC1N 2EB Company Incorporated in UK Address for service in India/Agents address: JATIN SHANTILAL POPAT. 308, Orchid Plaza, Behind Gokul Shopping Centre, Off. S.V. Road, Near Platform No.8, Borivali (West), Mumbai-400 092. Used Since :28/10/2015 MUMBAI Transportation Services, Arranging transport, Transport and Delivery tracking, Road and Water Transport management, Traffic and Transport information, Trasportation information, Trasport vehicle location, Transport brokerage, Tracking of freight, vehicle and pessanges. 4523 Trade Marks Journal No: 1994 , 05/04/2021 Class 39 3730888 18/01/2018 MR. RAHIM AMIN SHAIKH TRADING AS: AL QAMAR INTERNATIONAL TOURS AND TRAVEL FLAT NO. 28, C. T. S. NO. 5724, 5427, BHAKTI COMPLEX CHS., PIMPRI, CHINCHWAD, PUNE- 411018, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA Sole Proprietor Address for service in India/Attorney address: SAI ANAND SERVICE 73/3, SAI KRUPA CHS., POKHARAN ROAD NO-1, SHIVAI NAGAR, THANE (W)- 400 606, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA. Used Since :22/11/2016 MUMBAI TOURS & TRAVELS, TRAVEL ARRANGEMENT SERVICES 4524 Trade Marks Journal No: 1994 , 05/04/2021 Class 39 Master Overseas 3748029 08/02/2018 MANDEEP KAUR PROPRIETOR M/S MASTER OVERSEAS IST FLOOR, ABOVE MOR STORE, QADIAN CHUNGI, JALANDHAR ROAD,BATALA-143505(PUNJAB) SOLE PROPRIETOR Address for service in India/Agents address: HANDA ASSOCIATES G.T. -

The History of Punjab Is Replete with Its Political Parties Entering Into Mergers, Post-Election Coalitions and Pre-Election Alliances

COALITION POLITICS IN PUNJAB* PRAMOD KUMAR The history of Punjab is replete with its political parties entering into mergers, post-election coalitions and pre-election alliances. Pre-election electoral alliances are a more recent phenomenon, occasional seat adjustments, notwithstanding. While the mergers have been with parties offering a competing support base (Congress and Akalis) the post-election coalition and pre-election alliance have been among parties drawing upon sectional interests. As such there have been two main groupings. One led by the Congress, partnered by the communists, and the other consisting of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has moulded itself to joining any grouping as per its needs. Fringe groups that sprout from time to time, position themselves vis-à-vis the main groups to play the spoiler’s role in the elections. These groups are formed around common minimum programmes which have been used mainly to defend the alliances rather than nurture the ideological basis. For instance, the BJP, in alliance with the Akali Dal, finds it difficult to make the Anti-Terrorist Act, POTA, a main election issue, since the Akalis had been at the receiving end of state repression in the early ‘90s. The Akalis, in alliance with the BJP, cannot revive their anti-Centre political plank. And the Congress finds it difficult to talk about economic liberalisation, as it has to take into account the sensitivities of its main ally, the CPI, which has campaigned against the WTO regime. The implications of this situation can be better understood by recalling the politics that has led to these alliances. -

Dissolution of the Lok Sabha

DISSOLUTION OF THE LOK SABHA Tanusri Prasanna* Introduction The dissolution of the twelfth Lok Sabha on the twenty sixth day of April, 1999, by the President Mr. K.R. Narayanan, and the role of the latter in the intense political decision making preceding the same, have thrown open afresh the debate as to the exact role of the President as envisaged in the Constitution in the matter of dissolution. This paper attempts to analyse this issue in light of various controversial views on the subject. Pre-independence constitutional debates in India were influenced by two models of democratic government: the British Parliamentary system, and the Presidential system of the United States. In the final analysis the British model being closer home, "every instalment of constitutional reform was regarded as a step towards the establishment of a democratic and responsible government as it functioned in Britain."' Thus, it is widely accepted by various scholars that the founding fathers of the Constitution had opted for the parliamentary system of government. Working on this premise, the concepts such as executive decision making as well as delineating limits and laying a system of checks and balances on the different wings of the government as provided by the inherent federal structure, have been debated over and over again. However, when the Constitution actually came into force, a reading of its provisions sparked off a new line of thought as to the very nature of government, and the Presidential model of the United States which had been earlier rejected was now compared and contrasted.2 These discussions and debates were mainly concerned with the respective powers of the President and the Prime minister in the Constitution and in cases where both entities were strong the clash of opinions was soon recognised. -

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region August 2008 COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN MERRITT ISLAND NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Brevard and Volusia Counties, Florida U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia August 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 1 I. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose and Need for the Plan .................................................................................................... 3 U.S. Fish And Wildlife Service ...................................................................................................... 4 National Wildlife Refuge System .................................................................................................. 4 Legal Policy Context ..................................................................................................................... 5 National Conservation Plans and Initiatives .................................................................................6 Relationship to State Partners ..................................................................................................... -

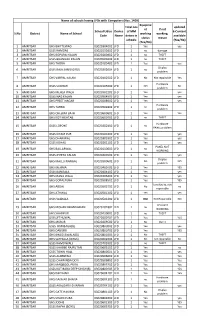

List of Schools Having Lfds

Name of schools having LFDs with Computers (Nos. 1400) Equipme Total nos updated nt If not School Udise Device of MM E-Content S.No District Name of School working working, Code Name deices in available status reason schools (Yes/No) (Yes/No) 1 AMRITSAR GHS BHITTEWAD 03020304002 LFD 1 Yes yes 2 AMRITSAR GSSS RAMDAS 03020111602 LFD 1 no damage 3 AMRITSAR GHS BOPARAI KALAN 03020200402 LFD 1 no THEFT 4 AMRITSAR GSSS BHANGALI KALAN 03020503002 LFD 1 no THEFT 5 AMRITSAR GHS THOBA 03020105402 LFD 1 Yes yes Display 6 AMRITSAR GSSS RAJA SANSI GIRLS 03020302604 LFD 1 no problem 7 AMRITSAR GHS VARPAL KALAN 03020402502 LFD 1 No Not repairable Yes Hardware 8 AMRITSAR GSSS SUDHAR 03020105002 LFD 1 NO No problem 9 AMRITSAR GHS MEHLA WALA 03020302202 LFD 1 Yes yes 10 AMRITSAR GSSS NAG KALAN 03020504903 LFD 1 Yes yes 11 AMRITSAR GHS PREET NAGAR 03020208902 LFD 1 Yes yes Hardware 12 AMRITSAR GHS TARPAI 03020502802 LFD 1 no problem 13 AMRITSAR GHS CHEEMA BATH 03020600602 LFD 1 Yes Yes 14 AMRITSAR GHS KOT MEHTAB 03020600702 LFD 1 no THEFT Hardware 15 AMRITSAR GSSS LOPOKE 03020202402 LFD 1 no PANEL problem 16 AMRITSAR GSSS KIYAM PUR 03020101002 LFD 1 Yes yes 17 AMRITSAR GHS DHARIWAL 03020303302 LFD 1 Yes yes 18 AMRITSAR GSSS KOHALI 03020201102 LFD 1 Yes yes PANEL NOT 19 AMRITSAR GHS BALLARWAL 03020110002 LFD 1 no WORKING 20 AMRITSAR GSSS JHEETA KALAN 03020400102 LFD 1 Yes yes Display 21 AMRITSAR GHS MALLU NANGAL 03020300602 LFD 1 No NO problem 22 AMRITSAR GHS MEHMA 03020400702 LFD 1 Yes YES 23 AMRITSAR GSSS BANDALA 03020404402 LFD 1 Yes yes 24 AMRITSAR GHS -

Afghanistan: Sikhs and Hindus

Country Policy and Information Note Afghanistan: Sikhs and Hindus Version 5.0 May 2019 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

Pincode Officename Statename Minisectt Ropar S.O Thermal Plant

pincode officename districtname statename 140001 Minisectt Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Thermal Plant Colony Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Ropar H.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Morinda S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140101 Bhamnara B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Rattangarh Ii B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Saheri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Dhangrali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Tajpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Lutheri S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Rollumajra B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Kainaur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Makrauna Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Samana Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Barsalpur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Chaklan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Dumna B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140103 Kurali S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Allahpur B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Burmajra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Chintgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Dhanauri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Jhingran Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Kalewal B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Kaishanpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Mundhon Kalan B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sihon Majra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Singhpura B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sotal B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Sahauran B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140108 Mian Pur S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Pathreri Jattan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Rangilpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Sainfalpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Singh Bhagwantpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Kotla Nihang B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140108 Behrampur Zimidari B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Ballamgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Purkhali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140109 Khizrabad West S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140109 Kubaheri B.O Mohali PUNJAB