The Blue Flower

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of the Western Rite Vicariate

A Short History of the Western Rite Vicariate Benjamin Joseph Andersen, B.Phil, M.Div. HE Western Rite Vicariate of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America was founded in 1958 by Metropolitan Antony Bashir (1896–1966) with the Right Reverend Alex- T ander Turner (1906–1971), and the Very Reverend Paul W. S. Schneirla. The Western Rite Vicariate (WRV) oversees parishes and missions within the Archdiocese that worship according to traditional West- ern Christian liturgical forms, derived either from the Latin-speaking Churches of the first millenium, or from certain later (post-schismatic) usages which are not contrary to the Orthodox Faith. The purpose of the WRV, as originally conceived in 1958, is threefold. First, the WRV serves an ecumeni- cal purpose. The ideal of true ecumenism, according to an Orthodox understanding, promotes “all efforts for the reunion of Christendom, without departing from the ancient foundation of our One Orthodox Church.”1 Second, the WRV serves a missionary and evangelistic purpose. There are a great many non-Orthodox Christians who are “attracted by our Orthodox Faith, but could not find a congenial home in the spiritual world of Eastern Christendom.”2 Third, the WRV exists to be witness to Orthodox Christians themselves to the universality of the Or- thodox Catholic Faith – a Faith which is not narrowly Byzantine, Hellenistic, or Slavic (as is sometimes assumed by non-Orthodox and Orthodox alike) but is the fulness of the Gospel of Jesus Christ for all men, in all places, at all times. In the words of Father Paul Schneirla, “the Western Rite restores the nor- mal cultural balance in the Church. -

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

Liturgical Calendar 2020-2021 of the Celtic Orthodox Church

Liturgical Calendar 2020-2021 of the Celtic Orthodox Church 1 Liturgical Calendar of the Celtic Orthodox Church 2020-2021 Translated from the French, published by Éditions Hol Levenez Le Bois Juhel 56130 Saint-Dolay, France Cover page: Icon of Saint John the Baptist 2020-2021 Introduction The calendar of the Celtic Orthodox Church begins on the first Sunday of November after All Saints Day (November 1st). This choice reconciles two traditions, one linked to the Syrian Orthodox Church tradition, which begins the liturgical year on the first Sunday of November (after All Saints Day), and the other according to an ancient Western non- Roman custom. It presents the Saints of the Universal Church as well as the principal Saints who have illuminated the history of the Celtic Orthodox Church. The Liturgical year opens before us as a permanent invitation to deepen our spirituality. The calendar answers, “present,” to the call to deepen our faith in Christ Jesus. The Sunday and feast-day readings are an inheritance of many centuries that belongs to our spiritual heritage. The liturgical cycle was developed over a period of time and set up by our Fathers under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. It is both a divine and human work, providentially proposed to our generation, in order that we may rediscover our spiritual roots in a world that is becoming more and more dechristianized. In this sense this calendar is prophetic for, drawing from ancient Western sources from before the Carolingian reforms, it is surprisingly suited to our times. This appears very clearly when we let ourselves be guided by this grouping together of feasts and readings that give rhythm to our daily life. -

2011 Census Definitions and Output Classifications

2011 Census Definitions and Output Classifications December 2012 Last Updated April 2015 Contents Section 1 – 2011 Census Definitions 6 Section 2 – 2011 Census Variables 49 Section 3 – 2011 Census Full Classifications 141 Section 4 – 2011 Census Footnotes 179 Footnotes – Key Statistics 180 Footnotes – Quick Statistics 189 Footnotes – Detailed Characteristics Statistics 202 Footnotes – Local Characteristics Statistics 280 Footnotes – Alternative Population Statistics 316 SECTION 1 2011 CENSUS DEFINITIONS 2011 Census Definitions and Output Classifications 1 Section 1 – 2011 Census Definitions 2011 Resident Population 6 Absent Household 6 Accommodation Type 6 Activity Last Week 6 Adaptation of Accommodation 6 Adult 6 Adult (alternative classification) 7 Adult lifestage 7 Age 7 Age of Most Recent Arrival in Northern Ireland 8 Approximated social grade 8 Area 8 Atheist 9 Average household size 9 Carer 9 Cars or vans 9 Catholic 9 Census Day 10 Census Night 10 Central heating 10 Child 10 Child (alternative definition) 10 Children shared between parents 11 Civil partnership 11 Cohabiting 11 Cohabiting couple family 11 Cohabiting couple household 12 Communal establishment 12 Communal establishment resident 13 Country of Birth 13 Country of Previous Residence 13 Current religion 14 Daytime population 14 Dependent child 14 Dwelling 15 Economic activity 15 Economically active 16 Economically inactive 16 Employed 16 2011 Census Definitions and Output Classifications 2 Section 1 – 2011 Census Definitions Employee 17 Employment 17 Establishment 17 Ethnic -

Equality Analysis Final April 2012

The Equality Act : Data Analysis Dr Christine Rivers Final Version April 2012 Contents 1.0 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………………………...…………..……….…..3 1.1 Equality Delivery System…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………..…….6 1.2 Local Population Data……………………………….……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….…..…………7 1.3 Structure of the report…………………………………….………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……....…….…..9 2.0 Service User Analysis ….……………………………….……………………..……………………………………………………………………………...........................…10 2.1 Engagement…………………...……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………...…11 2.2 Equality and Human Rights Training ………………….……………………….………………..…………………………………………………………………..…………....12 2.3 Gender…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……………….………..….13 2.4 Race/ethnicity………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……...…………………………………….……….13 2.5 Age…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………….………..15 2.6 Sexual Orientation……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...…….……….…….16 2.7 Religion/Belief……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…16 2.8 Transgender………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………..…..…..17 2.9 Pregnancy/Maternity…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….17 2.10 Disability………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…….…...17 2.11 Civil Partnership/marriage……………………………………………………………………………….……………………………………………………………………..…18 3.0 Workforce -

NEWSLETTER May, 2013

+ = = p^fkqp=mbqbo=^ka=m^ri=loqelalu=`ero`e NEWSLETTER May, 2013 Saints Peter and Paul Orthodox Church A Parish of the Orthodox Church in America Archpriest John Udics, Rector Deacon Mark Bohush 305 Main Road, Herkimer, New York, 13350 Parish Web Page: www.cnyorthodoxchurch.org CHRIST IS RISEN! ХРИСТОС ВОСКРЕСЕ! ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ ΑΝΕΣΤΗ! Saints Peter and Paul Orthodox Church Newsletter, May 2013 Parish Contact Information Clergy: Archpriest John Udics, Rector: (315) 866-3272 – [email protected] Deacon Mark Bohush – [email protected] Council President and Cemetery Director: John Ciko: (315) 866-5825 – [email protected] Council Secretary: Subdeacon Demetrios Richards (315) 865-5382 – [email protected] Sisterhood President: Rebecca Hawranick: (315) 822-6517 – [email protected] Birthdays in May 3 – Olga Hubiak 15 – Helen Gachowski 5 – Eva Ignafol 16 – Natalie Ptasznik 5 – Samantha Kinzey 26 – Samuel Kinzey 6 – Sandra Brelinsky 27 – John Kowansky 12 – Melissa Leigh 30 – Nancy Richards 13 – Susan Moore 31 – Anastasia Hawranick Memory Eternal 2 - Helen Nanoski 15 - Edmund Mamrosch Sr (1994) 2 - Paul Nadiak (1975) 16 - Panos Jarosz (1981) 2 - Anna Corman (2001) 16 - Mary Boguski (1983) 2 - Helen Nawoski (2004) 22 - Anne Williams (1988) 4 - Leon Lepkowski (1985) 24 - Kazmir Karpowich (1978) 7 - Harry Homyk Jr (1988) 24 - John Mezick (1988) 7 - William Steckler (2007) 24 - Metro Hrynda (1995) 9 - Harry Palyga (1976) 24 - Nicholas Tynda (1996) 9 - Frank Prawlocki 28 - Walter Alexczuk (1995) 11 - Catherine Foley (2002) 29 - Anna and Wasil -

Aprili - Juni 2014 1 HABARI ZA UNABII WA BIBLIA

Aprili - Juni 2014 1 HABARI ZA UNABII WA BIBLIA 3 24 31 33 KATIKA TOLEO HILI: 3 Maono, Historia, pamoja na Kanisa la Mungu Je, Mungu hutumia maono? Je, Shetani hutumia maono? Ni kwa namna ipi maono yameubadiri ulimwengu? 10 Ni nini kilizuka kule Fatima? Ni nini kilizuka kule Fatima, Ureno mnamo1917? Hili ni kwa sababu gani linaumuhimu kwa sasa? Je, Fatima inatoa dalili kuhusu Shetani na mpango wake? 14 Jisomee Kozi ya Biblia Somo la 2: Hapa tunakuletea habari njema . UJUMBE uliotumwa toka Mbinguni. Hili ni somo la pili la Kozi ya kuwasaidia watu wajisomee na kuielewa vema Biblia. 24 Pentekoste, Ndoto, pamoja na Karama za Kiroho. Aina mbalimbali za karama za kiroho zimetajwa katika Biblia. Je, zipo zozote miongoni mwake ambazo ni dhahiri kwa sasa? Vipi kuhusu ndoto? Fasiri (fafanuzi), maarifa, utambuzi, na upendo ni nini? 31 Je, unavumilia hadi mwisho? Baadhi katika Kanisa la Mungu wananuia “kung’ang’ana” hadi Kristo atakaporudi. Kimtazamo wao, “WANAVUMILIA” hadi mwisho (Math. 24:13) – lakini siyo kwa namna ambayo Kristo alitaka. 33 Evans Ochieng na Kanisa la Continuing Church of God: Makala hii inatoa utambulisho juu ya Bwana Evans Ochieng, Mchungaji wa Kanisa la Continuing Church of God anayeishi nchini Kenya. Jarada la Nyuma: Internet na Radio. Hili linaonyesha ni wapi watu wanaweza kuupata ujumbe kutoka Kanisa la Continuing Church of God. Kuhusu Jarada la Mbele: Mlinganisho baina ya sanamu ya kuchonga iliyoko Fatima (photo na Joyce Thiel) pamoja na ile sanamu itokanayo na ufafanuzi wa kile kinachodaiwa kuzuka na kuwatokea watu kule Fatima mwaka 1917 (sanaa na Brian Thiel pamoja na James Estoque). -

POCKET CHURCH HISTORY for ORTHODOX CHRISTIANS

A POCKET CHURCH HISTORY for ORTHODOX CHRISTIANS Fr. Aidan Keller © 1994-2002 ST. HILARION PRESS ISBN 0-923864-08-3 Fourth Printing, Revised—2002 KABANTSCHUK PRINTING r r ^ ^ IC XC NI KA .. AD . AM rr In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, amen. GOD INCARNATES; THE CHURCH FOUNDED OME 2,000 years ago, our Lord Jesus Christ directly intervened in human history. Although He S is God (together with the Father and the Holy Spirit), He became a man—or, as we often put it, He became incarnate —enfleshed. Mankind, at its very beginning in Adam and Eve, had fallen away from Divine life by embracing sin, and had fallen under the power of death. But the Lord Jesus, by His incarnation, death upon the Cross, and subsequent resurrection from death on the third day, destroyed the power death had over men. By His teaching and His whole saving work, Christ reconciled to God a humanity that had grown distant from God1 and had become ensnared in sins.2 He abolished the authority the Devil had acquired over men3 and He renewed and re-created both mankind and His whole universe.4 Bridging the abyss separating man and God, by means of the union of man and God in His own Person, Christ our Saviour opened the way to eternal, joyful life after death for all who would accept it.5 Not all the people of Judea, the Hebrews, God’s chosen people (Deut 7:6; Is 44:1), were ready to hear this news, and so our Lord spoke to them mostly in parables and figures. -

Beliefs of the Original Catholic Church

Beliefs of the Original Catholic Church Could a remnant group have continuing apostolic succession? What did early Church of God leaders, Greco-Roman saints, and others record? By Bob Thiel, Ph.D. “Polycarp … in our days was an apostolic and prophetic teacher, bishop/overseer in Smyrna of the Catholic Church. For every word which he uttered from his mouth both was fulfilled and will be fulfilled.” (Martyrdom of Polycarp, 16:2) “Contend for the faith once delivered to the saints” (Jude 3, Douay-Rheims) 1 Are all professing Christian churches, other than the Roman and Eastern Orthodox Catholics, Protestant? What did the original catholic church believe? Is there a church with those original beliefs today? THIS IS A PRELIMINARY DRAFT WITH CHANGES EXPECTED. Copyright © 2021 by Nazarene Books. ISBN 978-1-64106. Book produced for the: Continuing Church of God and Successor, a corporation sole, 1036 W. Grand Avenue, Grover Beach, California, 93433 USA. This is a draft edition not expected to be published before 2021. Covers: Edited Polycarp engraving by Michael Burghers, ca 1685, originally sourced from Wikipedia. Scriptural quotes are mostly taken from Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox approved Bibles like the Challoner Douay-Rheims (DRB), Original Rheims NT of 1582 (RNT 1582), New Jerusalem Bible (NJB), Eastern Orthodox Bible (EOB), Orthodox Study Bible (OSB), New American Bible (NAB), Revised Edition (NABRE), English Standard Version-Catholic Edition (ESVCE) plus also the A Faithful Version (AFV) and some other translations. The capitalized term ‘Catholic’ most often refers to the Roman Catholic Church in quotes. The use of these brackets { } in this book means that this author inserted something, normally like a scriptural reference, into a quote. -

December 2005

The Parish of St. Edmund, King and Martyr (Waterloo, Ontario) The Anglican atholic hurch of anada (A member of the "orldwide Traditional Anglican Communion) #PDATE December 7, 2005 - St. Ambrose January Schedule January 1 Sunday The Octave Day of Christmas / The Circumcision of Christ January ! Friday The Epiphany of Our Lord January & Sunday The First Sunday after the Epiphany January 13 Friday The Octave Day of the Epiphany / The Baptism of Our Lord January 15 Sunday The Second Sunday after the #$iphany January 22 Sunday The Third Sunday after the Epiphany January 25 Wednesday The Conversion of St. Paul January 29 Sunday The Fourth Sunday after the Epiphany Service Times and Location (1) 0,, Services are held in the Chapel at Luther Village on the Park - 139 Father David Bauer Drive in )aterloo. (2) On Sundays, Matins is sung at %&'&& a.m. .The Litany on the first Sunday of the month), and the Holy Eucharist is celebrated (sun2/ at %&'*& a.m. .'/ On 5eekdays - Major Holy Days - the Holy Eucharist is usually celebrated at ,'&& p.m., %&'&& a.m. on Saturday. Notes and Comments can have the feelin2s 5ithout the fact. Even when suppressed, ho5ever, the 1) Dr. (udzisze5ski continues his kno5,ed2e of guilt always produces certain examination of the cultura, slide of the objective needs, 5hich make their own demand for satisfaction irrespective of the mid-90s - The Revenge of Conscience - state of the feelin2s. These needs include the fourth of six parts - this page. confession, atonement, reconci,iation, and justification. 2) "or Robert's Ramblings - Matobo II - the second of two parts - see page 5. -

Repair and Restoration of Juneau Historic Site

Total Project Snapshot Report 2011 Legislature TPS Report 56264v2 Agency: Commerce, Community and Economic Development Grants to Named Recipients (AS 37.05.316) Grant Recipient: ROSSIA, Inc. Federal Tax ID: 71-0879791 Project Title: Project Type: Maintenance and Repairs ROSSIA, Inc. - Repair and Restoration of Juneau Historic Site State Funding Requested: $50,000 House District: Juneau Areawide (3-4) One-Time Need Brief Project Description: Repair and restoration of historic structure Saint Nicholas church in downtown Juneau. Currently used as a church and a major tourist destination and local landmark. Funding Plan: Total Project Cost: $372,500 Funding Already Secured: ($10,000) FY2012 State Funding Request: ($50,000) Project Deficit: $312,500 Funding Details: $10,000 National Parks Save America's Treasures 2012 $25,000 Rasmuson Foundation 2012 $5,000 Friends of St. Nicholas Church 2012 Detailed Project Description and Justification: ROSSIA, Inc. was founded in 2002 by Native corporation leaders, Orthodox clergy, government officials, architects, and historians who recognized the importance of preserving the cultural heritage associated with the Russian Orthodox Church in Alaska. ROSSIA, Inc. collaborates with local communities, encouraging and supporting their efforts to preserve the historic churches and along with it, a prominent part of Alaska’s history. Saint Nicholas Orthodox Church was built in 1893. Architecturally, the building is a beautiful example of the Russian American architecture and the unique octagon plan of St. Nicholas is the last of Alaska’s orthodox churches of this shape. It is toured by approximately 6,000 tourists each summer. The church is one of the most visited historic sites in Juneau and has been placed on the National Registry of Historic Places. -

The Word Documents

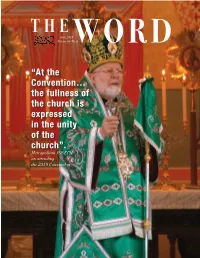

THE June 2019 Volume 63 No.WORD 6 “At the Convention… the fullness of the church is expressed in the unity of the church”. Metropolitan JOSEPH on attending the 2019 Convention EDITORIAL Volume 63 No.6 June 2019 COVER: THEWORD METROPOLITAN JOSEPH The Holy Synod Meeting of Antioch CONTENTS 3 EDITORIAL by Bishop JOHN to Address the 5 GRAND RAPIDS: YOU’LL LOVE IT HERE! Pastoral Challenges 8 THE CHALICE OF JOY by Fr. Peter Kavanaugh Facing Today’s Family 12 METROPOLITAN JOSEPH HOSTS RUSSIAN PATRIARCHAL BISHOPS AND CONSUL GENERAL OF RUSSIA 13 OUT OF YOUR HEAD, INTO THE RHYTHMS by Fr. John Oliver 20 THE SPACE BETWEEN VIRTUE AND PASSION: ST. MAXIMUS THE CONFESSOR by Nicholas A. Pappas 22 ST. CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA: DEFENDER OF THE THEOTOKOS by Fr. Daniel Daly 28 FOOD FOR HUNGRY PEOPLE PROGRAM 30 COMMUNITIES IN ACTION Letters to the editor are welcome and should include the author’s full name and parish. Submissions for “Commu- nities in Action” must be approved by the local pastor. Both may be edited for purposes of clarity and space. All submissions e-mailed and provided as a Microsoft Word text or editable PDF. Please do not embed artwork into the word documents. All art work must be high resolution: at least 300dpi. atriarch JOHN X of and faith. The Synod Fathers will discuss how Antioch has dedi we are to address the current situation regard ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION: U.S.A. and Canada, $40.00 cated the next Holy ing the family, and how we might meet the Foreign Countries, $50.00 Single Copies, $3.00 Synod to the Fam challenges at the parish and diocesan levels.