Painting Between the Wars: 1918–1940” by Daniel Robbins, 1964

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regionallst PAINTING and AMERICAN STUDIES Regionalism

REGiONALlST PAINTING AND AMERICAN STUDIES KENNETH J. LABUDDE Regionalism in American painting brings to mind immediately the period of the 1930's when the Middlewesterners JohnSteuart Curry, Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton enjoyed great reputation as the_ painters of Ameri can art. Curry, the Kansan; Benton, the Missourian; and Wood, the Iowan, each wandered off to New York, to Paris, to the great world of art, but each came home again to Kansas City, Cedar Rapids and Madison, Wisconsin. Only one of the three, Benton, is still living. At the recent dedication of his "Independence and the Opening of the West" in the Truman Library the ar tist declared it was his last big work, for scaffold painting takes too great a toll on a man now 72. Upon this occasion he enjoyed the acclaim of those gathered, but as a shrewdly intelligent, even intellectual man, he may have reflected that Wood and Curry, both dead foi* close to twenty years now, are slipping into obscur ity except in the region of the United States which they celebrated. Collec tors, whether institutional or private, who have the means and the interests to be a part of the great world have gone on to other painters. There are those who will say so much the worse for them, but I am content not to dwell on that issue but to speculate instead about art in our culture and the uses of art in cultural studies. I will explain that I am not convinced by those who hold with the conspir acy theory of art history, whether it be a Thomas Craven of yesterday or a John Canaday of today. -

Curry, John Steuart American, 1897 - 1946

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 Curry, John Steuart American, 1897 - 1946 Peter A. Juley & Son, John Steuart Curry Seated in Front of "State Fair," Westport, Connecticut, 1928, photograph, Peter A. Juley & Son Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum BIOGRAPHY John Steuart Curry was one of the three major practitioners of American regionalist painting, along with Thomas Hart Benton (American, 1889 - 1975) and Grant Wood (American, 1891 - 1942). Curry was born on a farm near Dunavant, Kansas, on November 14, 1897. His parents had traveled to Europe on their honeymoon, and his mother, Margaret, returned with prints of European masterworks that hung on the walls of the family home. She enrolled her son in art lessons at a young age, and his family supported his decision to drop out of high school in 1916 to study art. Curry worked for the Missouri Pacific Railroad and attended the Kansas City Art Institute for a month before moving to Chicago, where he studied at the Art Institute for two years. In 1918 he enrolled at Geneva College in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania. Curry decided to pursue commercial illustration, and in 1919 he began to study with illustrator Harvey Dunn in Tenafly, New Jersey. From 1921 to 1926, Curry’s illustrations appeared in publications such as the Saturday Evening Post and Boy’s Life. In 1923, while living in New York City, he married Clara Derrick; shortly thereafter he bought a studio at Otter Ponds near the art colony in Westport, Connecticut. In 1926 Curry stopped producing illustrations and left for Paris, where he took classes in drawing with the Russian teacher Vasili Shukhaev and studied old master paintings at the Louvre. -

Teachers for Additional Resources

for T Museum to the Classroom Joslyn Art Museum Comprehensive Study Lesson Plan Created by Mary Lou Alfieri, Josie Langbehn, Kristy Lee, Carter Leeka, Susan Oles, and Laura Huntimer. 1st Semester – American Regionalism Focus: American Regionalism, Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, and John Steuart Curry Objectives: • Understand and create personal narratives. • Recognize and identify American Regionalism artists and their works. • Learn about American culture including jazz. • Discover how these artists used their art to respond to movements such as lynch mobs. Instructional Strategies that Strongly Affect Student Achievement – Robert J. Marzano 01 Identifying similarities and differences 06 Cooperative learning 02 Summarizing and note taking 07 Setting goals and providing feedback 03 Reinforcing effort and providing recognition 08 Generating and testing hypotheses 04 Homework and practice 09 Activating prior knowledge 05 Nonlinguistic representations Resources: Check out the Teacher Support Materials online, and http://www.joslyn.org/education/teachers for additional resources Suggested Materials: Benton, Curry, and Wood teaching posters and prints, newsprint, charcoal, drawing pencils, recorders, Creating a Musical Dialogue lesson plan, 1900-24 Racial Tensions activities and lesson plan http://www.nebraskastudies.org/0700/resources/06race.pdf Vocabulary: agricultural terms, array, art terms, jazz, lynching, narrative, non-standard measurement terms, primary sources, Regionalism, rural. Procedure: • Engage: Introduce students to paintings by Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, and John Steuart Curry, and art movement, American Regionalism. Ask them how the phrase “lived experience” relates to the Regionalists’ works. Ask students to consider how lived experiences become part of their own narrative. • Art Talk: These three artists were defined as American Regionalists before they met. -

Kansas Curricular Standards for Visual Arts Are Aligned with the National Standards for the Visual Arts

Model Curricular Standards for Visual Arts State Board of Education May 2007 Kansas Curricular Standards for Visual Arts Joyce Huser Fine Arts Education Consultant Kansas State Department of Education 120 Southeast 10th Avenue, Topeka, Kansas, 66612-1182 [email protected] (785) 296-4932 Table of Contents Mission Statement ii Introduction iii Acknowledgements iv Document Usage v Major Objectives of Art Education vi What Constitutes a Quality Art Education? vii Standards, Benchmarks, Indicators, Instructional Samples 1 Basic 2 Intermediate 24 Proficient 46 Advanced 68 Exemplary 90 Scope and Sequence 112 Appendix I 128 Blooms Taxonomy 129 Assessments in Art 135 Kansas Art Teacher Licensure Standards 139 Competitions and Contests 142 Displaying Artwork 144 Shooting Slides of Student Work 145 Museums 146 Needs of Special Students 147 A Safe Work Environment 149 Stages of Artistic Development 151 Technology Time and Scheduling Standards 153 Appendix II 156 Resources/Books 157 Websites 159 Art Museums in Kansas with Educational Materials 162 Appendix III 165 Lesson Plans 166 Appendix IV 253 Glossary 254 i The Mission of the Kansas Curriculum Standards for the Visual Arts The visual arts are a vital part of every Kansas student’s comprehensive education. ii Introduction The Kansas Curricular Standards for the Visual Arts are designed for all visual art students and educators whether experienced or in the preservice years of their teaching career. A range of benchmarks engages students in reaching their greatest potential in the visual arts. Quality activities involve students in thoughtful, creative, and original expression of self. In all cases, students will learn life-skills including critical thinking, astute observation, viewing from multiple perspectives, higher order learning, and authentic problem-solving skills. -

Thomas Hart Benton

- Presentation – THOMAS HART BENTON September 2008 Who was Thomas Hart Benton? 1889 – Born in Neosho, MO to a famous political family. Started drawing at a young age – his created his first mural with crayons. Educated as an artist at the Art Institute of Chicago and Academie Julian in Paris. Thomas Hart Benton in his studio, 1936. Photo courtesy of The Kansas City Star. Who was Thomas Hart Benton? Originally influenced by European art, then experimented with abstraction Considered outspoken, opinionated and often abrasive and surrounded by controversy One of the principal Regionalists Through painting, Benton was able to support himself Source: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=14589825 Benton’s Techniques Early on attempted Modernism, Abstraction, Synchromism, Master Works Benton denounced the contemporary art of his time, but never fully broke from his Modernist roots Mural and canvas paintings focused on American history and sometimes “less savory” subjects of American life through varied subjects Early 1930s vs late 1930s Compare Benton and Michelangelo’s artworks New York Rooftops, c. 1920-23 Thomas Hart Benton, The Bather, 1917 Michelangelo Buonaratti, Figure from the Sistine Chapel, Rome, 1508-1512 Benton’s Techniques “Sold out” in a sense by creating artworks for the tobacco industry and the military. His canvas - dramatic action, loud colors, sculptural volumes He intended to create distinctly American art Landscapes in his later years have a “feeling of harmony between man and nature” Tobacco Sorters, 1944 Picnic, 1952 Private Collection Benton and Pollock The Teacher and The Pupil Benton taught Pollock at the Art Students League of New York Regionalists influenced Abstract Expressionists Compare Benton and Pollock’s works Jackson Pollock n 1928. -

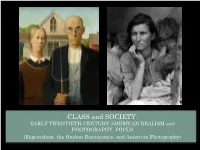

CLASS and SOCIETY

CLASS and SOCIETY: EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN REALISM and PHOTOGRAPHY: FOCUS (Regionalism, the Harlem Renaissance, and American Photography) ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://www.phillipscollection.org/r esearch/american_art/artwork/La wrence-Migration_Series1.htm TITLE or DESIGNATION: Migration of the Negro series ARTIST: Jacob Lawrence CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Early American Modernism DATE: 1940-1941 C.E. MEDIUM: tempera on hardboard ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://smarthistory.khanac ademy.org/american- regionalism-grant-woods- american-gothic.html TITLE or DESIGNATION: American Gothic ARTIST: Grant Wood CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: American Regionalism DATE: 1930 C. E. MEDIUM: oil on beaverboard ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://smarthistory.khan academy.org/hoppers- nighthawks.html TITLE or DESIGNATION: Nighthawks ARTIST: Edward Hopper CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Twentieth-Century American Realism DATE: 1942 C.E. MEDIUM: oil on canvas TITLE or DESIGNATION: Migrant Mother, Nipomo Valley ARTIST: Dorothea Lange CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Twentieth-Century American Photography DATE: 1935 C. E. MEDIUM: gelatin silver print CLASS and SOCIETY: EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN REALISM and PHOTOGRAPHY: SELECTED TEXT (Regionalism, the Harlem Renaissance, and American Photography) EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN REALISM and PHOTOGRAPHY Online Links: Jacob Lawrence's Migration Series - Philiips Collection Hopper's Nighthawks – Smarthistory Grant Wood's American Gothic Grant Wood's American Gothic - Art Institute of Chicago Top Left: -

Oklahoma Today November-December 1985 Volume

NOVEMBER-DECEMBER '85 SQUARE DANCE: RUFFLES, RlCK RACK & YELLOW ROCKS HAM FOR THE H0LInIYS: THE OKLAHOMA SMOKEHOUeF - I SQUARE DANCE ROUNPUP I If the words squaw hnce make you Y think of Gene Autry movies or junior high gym class, come to Oklahoma City this November. Some 5,000 Sooners just may t convince you there's more to it than rick rack and do sa dos. LAST OF THE BIG TOPS I ,0 I Have a yen for circus the way it used to 10 be? ~ookno further than Hugo and the HAM OPERATORS Carson & Barnes Circus, the biggest outfit still under canvas-and the greatest On the shores of Grand Lake, some show in Oklahoma. Green Country entrepreneurs took a dollop of 19th-century expertise, added a dash of microchi~sand cooked up 7V The circus at home-in a flourishing business, heOklahoma Hugo. Photo by Phillip Smokehouse. I OKLAHOMA PORTFOLIO Radcliffe. Inside front. Fall A seasonal sampler by photographer scene near Spavinaw dam. Ivan McCartney. Photo by Howard Robson. 22 Back. Autumn oak, Wichita THE MONK, THE MUMMT Mountains. Photo by Steve & MABEE - Wilson. RlDlNQ HERD ON THE WEST Meet Mr. Jim Jordan of No Man's Land. DEPARTMENTS FEATURES Today in Oklahoma ....................................4 BookdLetters...........................................4-5 8 I It took a monk. an oilman and Uncommon Common Folk .........................6 Princess ~enndof the 23rd Dynasty Oklahoma Omnibus...................................17 CULTIVATING CHRISTMAS - I to create one of the state's most Destinations: Remm Bend .....................38 Not many farmers can claim a holiday distinctive museums-the Mabee-Gerrer On to Oklahoma.........................................49 tradition as their cash crop. -

Harries Thesis FINAL

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Communication Arts and Sciences THE CONTESTABLE JOHN BROWN: ABOLITIONISM AND THE CIVIL WAR IN U.S. PUBLIC MEMORY A Thesis in Communication Arts and Sciences by Anne C. Harries © 2011 Anne C. Harries Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts December 2011 ii The thesis of Anne C. Harries was reviewed and approved* by the following: J. Michael Hogan Liberal Arts Research Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Stephen H. Browne Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Jeremy Engels Assistant Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Kirt H. Wilson Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Director of Graduate Studies *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Abolitionist John Brown is a divisive figure in United States history. He features prominently in our national historical narrative, but his radical politics, religious fanaticism, and violent methods have led to polarized memories of his contributions to the abolitionist cause and his role in the coming of the U.S. Civil War. Some consider Brown a hero or a martyr of abolitionism, while others view him as a violent extremist, even a madman. Over time, Americans from across the political spectrum have mobilized Brown’s memory to advance particular political and social causes, sometimes on opposing sides of the same issue. This thesis examines three instances of public controversy over the memory of John Brown. In each of these case studies, Brown’s public memory has been rhetorically constructed and vigorously contested. First, I explore a controversy over regionalist painter John Steuart Curry’s depiction of Brown in the Kansas Statehouse mural, The Tragic Prelude. -

Paul Cadmus As Exemplary Foil to a Homegrown American Art Maxine Marks

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Art & Art History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2014 Touching Nether-Regionalisms: Paul Cadmus as Exemplary Foil to a Homegrown American Art Maxine Marks Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/arth_etds Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Marks, Maxine. "Touching Nether-Regionalisms: Paul Cadmus as Exemplary Foil to a Homegrown American Art." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/arth_etds/25 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art & Art History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maxine Roush Marks Candidate Art & Art History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Dr. Kirsten Pai Buick, Chairperson Aaron Fry Dr. Catherine Zuromskis i TOUCHING NETHER-REGIONALISMS: PAUL CADMUS AS EXEMPLARY FOIL TO A HOMEGROWN AMERICAN ART by MAXINE ROUSH MARKS B.A.F.A. ART HISTORY THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO 2006 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2014 ii Dedication For Dad — In memory of your curious, adventurous and kind life. iii Acknowledgments In gratitude and with love for my husband, my mother, my brother, my deceased father, all of whom have always been daring in their adventures and generous with their love. -

254 Kansas History a New Chronology of the Development of John Steuart Curry’S Murals for the Rotunda of the Kansas State Capitol

John Steuart Curry, The Homestead and Building of the Barbed Wire Fence, 1937-1939, as depicted in a mural at the Interior Department in Washington D.C. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, photo by Carol M. Highsmith. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 43 (Winter 2020-21): 254–271 254 Kansas History A New Chronology of the Development of John Steuart Curry’s Murals for the Rotunda of the Kansas State Capitol by Julia R. Myers n May 1942, Kansan John Steuart Curry traveled to Topeka to put the “finishing touches on the [Tragic Prelude and Kansas Pastoral] murals,” which he had started painting on the Kansas State Capitol’s second floor in the summer of 1940.1 There he had intended to create, in his words, a “historicalI allegory” that would tell the story of Kansas. The allegory begins in the east corridor with the Tragic Prelude, which depicts both the Spanish conquistador Francisco Coronado, who arrived in Kansas in 1541, and the abolitionist John Brown, who fought against proslavery forces in 1856 during the period known as Bleeding Kansas. The eight murals in the rotunda, which were never painted, would have told the history of Kansas in more detail with scenes from both before and after 1856, including references to early settlement by whites and the Dust Bowl. In the west corridor, Kansas Pastoral (Fig. 1) portrays, in Curry’s words, “the ideal unmortgaged farm home,” a hopeful vision at a time when many Kansas family farms were in foreclosure or on the edge of it, as was the Curry family farm in 1938–1939.2 Curry scholar Patricia Junker considers the statehouse mural cycle, even in its incomplete state, one of the “crowning Julia R. -

Biographical Dictionary of Kansas Artists (Active Before 1945)

Biographical Dictionary of Kansas Artists (active before 1945) Compiled by Susan V. Craig, Art & Architecture Librarian Univ. of Kansas August 2006 1 This book began with a 1981 reference question about John Noble, a name I did not recognize despite having studied art history and worked as an art librarian for more than 10 years. Learning that John Noble was a Kansas artist, I went looking for the best available book on Kansas art only to learn the resources were few. As a new faculty member at the Univ. of Kansas, I needed to establish a research project so I decided to prepare a dictionary of Kansas artists thus fulfilling both the research requirement and educating myself about the history of the visual arts in my native state; I just didn't intend the project to take 25 years or realize that I would have more than 1750 entries in the dictionary. I began by defining the scope of the work: • "Kansas artist" was loosely defined as artists who were both born in the state as well as artists who were born elsewhere but were artistically active in Kansas. Under this latter definition, I included artists who produced significant artworks such as the murals installed in Kansas post offices. Occasionally, artists who lived or worked primarily in Kansas City, MO may be included. I did not deliberately include all Kansas City artists but neither did I exclude them if the name came from a Kansas source such as the Kansas State Gazetteer. • Another choice I made was to look for artists who were artistically active before 1945. -

Print Study Sheet

TRAGIC PRELUDE by John Steuart Curry 1897-1946 John Steuart Curry was born in 1897 in the state of Kansas. When he was 18, he left home to study art in Kansas City and Chicago. He made a living by illustrating books and magazines. For eight months he studied in Paris, France. When he returned from Paris, he moved to Connecticut. There he painted "The Baptism". People were not painting about this subject at the time, but a wealthy woman saw it. She liked it so well that she told Curry that she would support him financially. Baptism in Kansas was an oil painting created in 1928. Notice the white robes of the other candidates for baptism. It is a large painting, 40x50 inches, containing bright colors and many details. He has included birds in the picture reminiscent of the dove which appeared at the baptism of Jesus. (Look at the link, "Article about Curry" to read an article about him. You can click on the Real Audio link and hear the interview that is recorded here.) Curry's painting Tragic Prelude is a mural painted in the Kansas State Capitol. It shows John Brown, an anti-slavery leader before the Civil War. In 1859 he was hanged for leading a raid on the arsenal at Harper's Ferry, Virginia. The state of Kansas asked him to paint the mural in the state house, but they didn't agree with his ideas for the pictures, and they asked him to stop painting it. He was very upset and wouldn't even sign the paintings that he had already finished.