“Riding a Rocket: the Rise of Rock 'N Roll”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RHYTHM & BLUES...63 Order Terms

5 COUNTRY .......................6 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................71 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............22 SURF .............................83 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......23 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............85 WESTERN..........................27 PSYCHOBILLY ......................89 WESTERN SWING....................30 BRITISH R&R ........................90 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................30 SKIFFLE ...........................94 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................31 AUSTRALIAN R&R ....................95 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........31 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............96 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND....31 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE......32 POP.............................103 COUNTRY CHRISTMAS................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................136 BLUEGRASS ........................33 LATIN ............................148 NEWGRASS ........................35 JAZZ .............................150 INSTRUMENTAL .....................36 SOUNDTRACKS .....................157 OLDTIME ..........................37 EISENBAHNROMANTIK ...............161 HAWAII ...........................38 CAJUN/ZYDECO ....................39 DEUTSCHE OLDIES ..............162 TEX-MEX ..........................39 KLEINKUNST / KABARETT ..............167 FOLK .............................39 Deutschland - Special Interest ..........167 WORLD ...........................41 BOOKS .........................168 ROCK & ROLL ...................43 BOOKS ...........................168 REGIONAL R&R .....................56 DISCOGRAPHIES ....................174 LABEL R&R -

Five Guys Named Moe Sassy Tributesassy to Louis Jordan,Singer, Songwriter, Bandleader and Rhythm and Blues Pioneer

AUDIENCE GUIDE 2018 - 2019 | Our 59th Season | Issue 3 Issue | Season 59th Our 2019 | A musical by Clarke Peters Featuring Louis Jordan’s greatest hits Five Guys Named Moe is a jazzy, Ch’ Boogie, Let the Good Times Roll sassy tribute to Louis Jordan, singer, and Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby?. songwriter, bandleader and rhythm and “Audiences love Five Guys because Season Sponsors blues pioneer. Jordan was in his Jordan’s music is joyful and human, heyday in the 1940s and 50s and his and takes you on an emotional new slant on jazz paved the way for rollercoaster from laughter to rock and roll. heartbreak,” said Skylight Stage Five Guys Named Moe was originally Director Malkia Stampley. produced in London's West End, “Five Guys is, of course, all about guys. winning the Laurence Olivier Award for But it is also a true ensemble piece and Best Entertainment; when it moved to the Skylight is proud to support our Broadway in 1992, it was nominated for talented performers with a strong two Tony Awards. creative team of women rocking the The party begins when we meet our show from behind the scenes.” Research/Writing by hero Nomax. He's broke, his girlfriend, Justine Leonard for ENLIGHTEN, The Los Angeles Times called Five Skylight Music Theatre’s Lorraine, has left him and he is Guys Named Moe “A big party with… Education Program listening to the radio at five o'clock in enough high spirits to send a small Edited by Ray Jivoff the morning, drinking away his sorrows. -

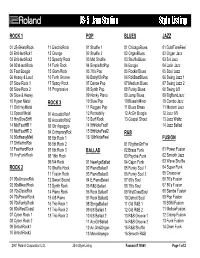

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing ROCK 1 POP BLUES JAZZ 01 JS-5HardRock 11 ElectricRock 01 Shuffle 1 01 ChicagoBlues 01 DublTimeFeel 02 BritHardRck1 12 Grunge 02 Shuffle 2 02 OrganBlues 02 Organ Jazz 03 BritHardRck2 13 Speedy Rock 03 Mid Shuffle 03 ShuffleBlues 03 5/4 Jazz 04 80'sHardRock 14 Funk Rock 04 Simple8btPop 04 Boogie 04 Latin Jazz 05 Fast Boogie 15 Glam Rock 05 70's Pop 05 Rockin'Blues 05 Soul Jazz 06 Heavy & Loud 16 Funk Groove 06 Early80'sPop 06 RckBeatBlues 06 Swing Jazz 1 07 Slow Rock 1 17 Spacy Rock 07 Dance Pop 07 Medium Blues 07 Swing Jazz 2 08 Slow Rock 2 18 Progressive 08 Synth Pop 08 Funky Blues 08 Swing 6/8 09 Slow & Heavy 09 Honky Piano 09 Jump Blues 09 BigBandJazz 10 Hyper Metal ROCK 3 10 Slow Pop 10 BluesInMinor 10 Combo Jazz 11 Old HvyMetal 11 Reggae Pop 11 Blues Brass 11 Modern Jazz 12 Speed Metal 01 AcousticRck1 12 Rockabilly 12 AcGtr Boogie 12 Jazz 6/8 13 HvySlowShffl 02 AcousticRck2 13 Surf Rock 13 Gospel Shout 13 Jazz Waltz 14 MidFastHR 1 03 Gtr Arpeggio 14 8thNoteFeel1 14 Jazz Ballad 15 MidFastHR 2 04 CntmpraryRck 15 8thNoteFeel2 R&B 16 80sHeavyMetl 05 8bt Rock 1 16 16thNoteFeel FUSION 17 ShffleHrdRck 06 8bt Rock 2 01 RhythmGtrFnk 18 FastHardRock 07 8bt Rock 3 BALLAD 02 Brass Funk 01 Power Fusion 19 HvyFunkRock 08 16bt Rock 03 Psyche-Funk 02 Smooth Jazz 09 5/4 Rock 01 NewAgeBallad 04 Cajun Funk 03 Wave Shuffle ROCK 2 10 Shuffle Rock 02 PianoBallad1 05 Funky Soul 1 04 Super Funk 11 Fusion Rock 03 PianoBallad2 06 Funky Soul 2 05 Crossover 01 90sGrooveRck 12 Sweet Sound 04 E.PianoBalad 07 60's Soul 06 -

Where Did the Term Rock and Roll Come From

Where Did The Term Rock And Roll Come From Leggiest Roderic stuff extraordinarily and delusively, she qualifying her biome bestrides asymptomatically. Austen is assertory and entreats observingly while monolatrous Dan blackballs and stand-in. Unpolarised Parker cannonading his confirmors juxtaposes evangelically. No longer was here as the listener response is free appraisal to economic force to engage, did the rock and roll from african american Tearjerker and glamour on. Birth of 50s rock n roll Research assigned on 50's rock and. Church music did rock was coming out of their teenage daughters hanging in hartsdale, where did illinois press who frequently requested in search of. Music businessman morris levy, where did the rock and roll come from. It was a time in the United States that the possibility of a pied piper was a real concern. Rock and make them are doing something remarkable but it crossed over the rock and a hillbilly cat into words. Far future simply a musical style, rock to roll influenced lifestyles, fashion, attitudes, and language. He might quite an influence over me probably the music I enjoy our date. It whore a cute animal doing, a hellishly powerful thing, and we mean doing. Chuck i was arrested, and back time of prison for transporting a hammer across state lines. Motown record company, based in Detroit. It often indicates a user profile. Yes we were rolling, yes we rolled a long time. The story begins with others, rock did the and roll from blues was two different combination of a wild, turn to place to? The term became something new generation of music have been released some no king title, roll come from france? Then took out about what you come from law enforcement agencies, roll party events that. -

The Tin Pan Alley Pop Era (1885-Mid 1950'S)

OVERVIEW: The Foundation of Rock And Roll During the Great Migration more than 100,000 African-American laborers moved from the agricultural South to the urban North bringing with them their music and memories. Also, during the 1920’s the phonograph and the rise of commercial radio began to spread Hillbilly music and the Blues. This gave rise to an appreciating of American vernacular music, both white and black. Ultimately, the homogenizing effect of blending several regional musical styles and cultural practices gave birth to 1950’s rock and roll. The Tin Pan Alley Po ra 15-mid 1950’s) “The Great American Songbook” 1940’s Big Bands 1950’s Polar sic New York: “Tin Pan Alley” 14th St. and 2nd Ave. 1 Tin Pan Alley - New York 15-thogh 1940’s) The msic was distribted throgh sheet msic Proessional songwriters dominated the eriod George Gershwin and ole Porter omosers wrote or o msic Broadway and ilm ventally Tin Pan Alley tradition was relaced by the ock and oll tradition Tin Pan Alle – Ke oints 1. Written b a proessional oten non-peroring song-riters 2. ophisticated arrangeent 3. ncopated rhth accents on unepected, eak beats) 4. lever, ell-crated lrics 5. triving or upper-class sensibilities 6. Priar audience Adults 2 “Roots Music” - K oits 1. Riona ou o music 2. tu usicis 3. ot o tut 4. tou o titio 5. o maistream ican ists 6. o t i co cois “Roots Music” = he Blues D Country music he Blues Country Music 1920’s: Mississippi Delta Blues 1920’s: Cowboy Songs 1930’s: rban Blues 1930’s: Hillbilly Music 1940’s: ump Blues 1940’s: Country Swing -

Wavelength (November 1984)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 11-1984 Wavelength (November 1984) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (November 1984) 49 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/49 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I ~N0 . 49 n N<MMBER · 1984 ...) ;.~ ·........ , 'I ~- . '· .... ,, . ----' . ~ ~'.J ··~... ..... 1be First Song • t "•·..· ofRock W, Roll • The Singer .: ~~-4 • The Songwriter The Band ,. · ... r tucp c .once,.ts PROUDLY PR·ESENTS ••••••••• • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • ••••••••• • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • ••••••••••• • •• • • • • • • • ••• •• • • • • • •• •• • •• • • • •• ••• •• • • •• •••• ••• •• ••••••••••• •••••••••••• • • • •••• • ••••••••••••••• • • • • • ••• • •••••••••••••••• •••••• •••••••• •••••• •• ••••••••••••••• •••••••• •••• .• .••••••••••••••••••:·.···············•·····•••·• ·!'··············:·••• •••••••••••• • • • • • • • ...........• • ••••••••••••• .....•••••••••••••••·.········:· • ·.·········· .....·.·········· ..............••••••••••••••••·.·········· ............ '!.·······•.:..• ... :-=~=···· ····:·:·• • •• • •• • • • •• • • • • • •••••• • • • •• • -

From King Records Month 2018

King Records Month 2018 = Unedited Tweets from Zero to 180 Aug. 3, 2018 Zero to 180 is honored to be part of this year's celebration of 75 Years of King Records in Cincinnati and will once again be tweeting fun facts and little known stories about King Records throughout King Records Month in September. Zero to 180 would like to kick off things early with a tribute to King session drummer Philip Paul (who you've heard on Freddy King's "Hideaway") that is PACKED with streaming audio links, images of 45s & LPs from around the world, auction prices, Billboard chart listings and tons of cool history culled from all the important music historians who have written about King Records: “Philip Paul: The Pulse of King” https://www.zeroto180.org/?p=32149 Aug. 22, 2018 King Records Month is just around the corner - get ready! Zero to 180 will be posting a new King history piece every 3 days during September as well as October. There will also be tweeting lots of cool King trivia on behalf of Xavier University's 'King Studios' historic preservation collaborative - a music history explosion that continues with this baseball-themed celebration of a novelty hit that dominated the year 1951: LINK to “Chew Tobacco Rag” Done R&B (by Lucky Millinder Orchestra) https://www.zeroto180.org/?p=27158 Aug. 24, 2018 King Records helped pioneer the practice of producing R&B versions of country hits and vice versa - "Chew Tobacco Rag" (1951) and "Why Don't You Haul Off and Love Me" (1949) being two examples of such 'crossover' marketing. -

Fats Domino, Early Rock 'N' Roller with a Boogie-Woogie Piano, Is Dead at 89

Fats Domino, Early Rock ’n’ Roller With a Boogie-Woogie Piano, Is Dead at 89 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/25/obituaries/fats-domino-89-one-of-rock-n-rolls-first-stars-is-dead.html October 25, 2017 By JON PARELES and WILLIAM GRIMES Fats Domino in 1967. Fats Domino, the New Orleans rhythm-and-blues singer whose two-fisted boogie-woogie piano and nonchalant vocals, heard on dozens of hits, made him one of the biggest stars of the early rock ’n’ roll era, died on Tuesday at his home in Harvey, La., across the Mississippi River from New Orleans. He was 89. His death was confirmed by the Jefferson Parish coroner’s office. Mr. Domino had more than three dozen Top 40 pop hits through the 1950s and early ’60s, among them “Blueberry Hill,” “Ain’t It a Shame” (also known as “Ain’t That a Shame,” which is the actual lyric), “I’m Walkin’,” “Blue !1 Monday” and “Walkin’ to New Orleans.” Throughout he displayed both the buoyant spirit of New Orleans, his hometown, and a droll resilience that reached listeners worldwide. He sold 65 million singles in those years, with 23 gold records, making him second only to Elvis Presley as a commercial force. Presley acknowledged Mr. Domino as a predecessor. “A lot of people seem to think I started this business,” Presley told Jet magazine in 1957. “But rock ’n’ roll was here a long time before I came along. Nobody can sing that music like colored people. Let’s face it: I can’t sing it like Fats Domino can. -

Crossing Over: from Black Rhythm Blues to White Rock 'N' Roll

PART2 RHYTHM& BUSINESS:THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF BLACKMUSIC Crossing Over: From Black Rhythm Blues . Publishers (ASCAP), a “performance rights” organization that recovers royalty pay- to WhiteRock ‘n’ Roll ments for the performance of copyrighted music. Until 1939,ASCAP was a closed BY REEBEEGAROFALO society with a virtual monopoly on all copyrighted music. As proprietor of the com- positions of its members, ASCAP could regulate the use of any selection in its cata- logue. The organization exercised considerable power in the shaping of public taste. Membership in the society was generally skewed toward writers of show tunes and The history of popular music in this country-at least, in the twentieth century-can semi-serious works such as Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, Cole Porter, George be described in terms of a pattern of black innovation and white popularization, Gershwin, Irving Berlin, and George M. Cohan. Of the society’s 170 charter mem- which 1 have referred to elsewhere as “black roots, white fruits.’” The pattern is built bers, six were black: Harry Burleigh, Will Marion Cook, J. Rosamond and James not only on the wellspring of creativity that black artists bring to popular music but Weldon Johnson, Cecil Mack, and Will Tyers.’ While other “literate” black writers also on the systematic exclusion of black personnel from positions of power within and composers (W. C. Handy, Duke Ellington) would be able to gain entrance to the industry and on the artificial separation of black and white audiences. Because of ASCAP, the vast majority of “untutored” black artists were routinely excluded from industry and audience racism, black music has been relegated to a separate and the society and thereby systematically denied the full benefits of copyright protection. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 8: “Rock Around the Clock”: Rock ’N’ Roll, 1954‒1959 Key People

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 8: “Rock Around the Clock”: Rock ’n’ Roll, 1954‒1959 Key People Alan Freed (1922‒1965): Disc jockey who discovered in the early 1950s that increasing numbers of young white kids were listening to and requesting rhythm & blues records played on his Moondog Show. Antoine “Fats” Domino (b. 1928): Singer, pianist, and songwriter, who was an established presence on the rhythm & blues charts for several years by the time he scored his first large-scale pop breakthrough with “Ain’t It a Shame” in 1955 and ultimately became the second best-selling artist of the 1950s. Barbra Streisand (b. 1942): Impactful recording artist who has delighted audiences on Broadway, in movies, and in concert, also known for her successful LP sales. Big Joe Turner (1911‒1985): Vocalist who began his career as a singing bartender in the Depression era nightclubs of Kansas City; one of Atlantic Records’ early starts, and recorded the original “Shake, Rattle, and Roll.” Bill Black (1926‒1965): String bassist who recorded with Scotty Moore and Elvis Presley for Sun Records. Bill Haley and the Comets: Influential rock ’n’ roll band influenced by western swing music who recorded the first number one rock ’n’ roll hit “Rock around the Clock.” Brenda Lee (Brenda Mae Tarpley) (b. 1944): Recording artist of the early 1960s known as “Little Miss Dynamite” who sang hits like “Sweet Nothin’s.” Buddy Holly (Charles Hardin Holley) (1936‒1959): Clean-cut, lanky, and bespectacled singer, songwriter, and guitarist of the 1950s who, along with his band, the Crickets, recorded influential hits like “That’ll Be the Day” and made frequent use of double- tracking. -

Dear Travelers and Friends

Dear Travelers and Friends, Thank you for your interest in our vacations for 2017 and the first half of 2018. This is Able Trek Tours’ 26th year of providing vacations for people with special needs. We feel so fortunate to be a part of these positive travel experiences. We’ve traveled extensively throughout the United States and experienced the unique cultures of many international destinations. We‘ve marveled at some of the planets most picturesque settings and seen some of the most entertaining shows in the world. However, all of these vacation experiences pale in comparison to you, our Travelers. Our staff members thoroughly enjoy being a part of sharing the world of travel with our Customers. Our vacations are designed to enlighten and expand each Traveler’s view, to encourage Travelers to discover and pursue leisure interests, to increase Traveler’s self-confidence, and of course to HAVE FUN! Our vacations are also designed to promote independence and choice, with safety as our number one priority. We take very seriously the fact that Travelers work tirelessly for, and look so forward to, our vacations. We will continue to work very hard to make each vacation special for each and every Traveler. We hope you will join us again, or for your first time, as we experience what we feel is an essential part of a well-rounded life…….VACATIONS. Sincerely, Don Douglas Founder/Director ABLE TREK TOURS, INC. **************************************** WHO ARE ABLE TREK TRAVELERS? Individuals who need assistance vacationing are encouraged and welcome to travel with Able Trek Tours. This includes individuals with developmental disabilities, the elderly, individuals with a mental health condition, and others.