Girl Talk's Indefinite Role in the Digital Sampling Saga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law Ledger

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW LEDGER VOLUME 1 WINTER 2009 NUMBER 1 MIXED SIGNALS: TAKEDOWN BUT DON’T FILTER? A CASE FOR CONSTRUCTIVE AUTHORIZATION * VICTORIA ELMAN AND CINDY ABRAMSON Scribd, a social publishing website, is being sued for copyright infringement for allowing the uploading of infringing works, and also for using the works themselves to filter for copyrighted work upon receipt of a takedown notice. While Scribd has a possible fair use defense, given the transformative function of the filtering use, Victoria Elman and Cindy Abramson argue that such filtration systems ought not to constitute infringement, as long as the sole purpose is to prevent infringement. American author Elaine Scott has recently filed suit against Scribd, alleging that the social publishing website “shamelessly profits” by encouraging Internet users to illegally share copyrighted books online.1 Scribd enables users to upload a variety of written works much like YouTube enables the uploading of video * Victoria Elman received a B.A. from Columbia University and a J.D. from Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she was a Notes Editor of the Cardozo Law Review. She will be joining Goodwin Procter this January as an associate in the New York office. Cindy Abramson is an associate in the Litigation Department in the New York office of Morrison & Foerster LLP. She recieved her J.D. from the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she completed concentrations in Intellectual Property and Litigation and was Senior Notes Editor of the Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Morrison & Foerster, LLP. -

A Collection of Short and Nonfiction

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Spring 5-1-2018 Unlonely: A Collection of Short and Nonfiction Mary Karnes University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Karnes, Mary, "Unlonely: A Collection of Short and Nonfiction" (2018). Master's Theses. 359. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/359 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unlonely: a Collection of Short and Nonfiction by Mary Ryan Karnes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters and the Department of English at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by: Angela Ball, Committee Chair Anne Sanow Charles Sumner Justin Taylor ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Angela Ball Dr. Luis Iglesias Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Department Chair Dean of the Graduate School May 2018 COPYRIGHT BY Mary Ryan Karnes 2018 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT The following short stories and nonfiction essays were produced by the author during her writing career at the University of Southern Mississippi. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The following work took shape under the counsel of Steve Barthelme, Anne Sanow, and Justin Taylor, all incredible writers and mentors. Steve pushed me toward adulthood in my writing; Anne encouraged me to take risks and to consider form at every turn; Justin saw my work’s strengths where I could only see it faltering. -

Dark Canadee

Dark Canadee The Fifth Voyage Previously on DARK CANADEE… ‘Our work on poems is no longer a secret…’ ‘I’ve got a commission, the Ballad of the Banshee!’ ‘There’s no banshee. The spirits are many women, they come to that window…’ ‘The three tommies, the night they entered your workshop…what on earth did you give them in there?’ ‘One of them ate the paper…’ ‘He is trying to be the white space for the women to survive in…’ ‘the Deal Porters keep staring at us, and the merchants reckon we’re witches…’ ‘Kemp is gone?’ ‘Thank God…’ ‘Weir the Wagoneer, hat your service!’ ‘What are you doing here Kemp…’ ‘I love Max! always just a tad behind the times…’ ‘McCloud!’ ‘I’ll remember for you, Max: three women cry but where have they gone?’ ‘I loves a riddle, Miss Cloud!’ ‘Don’t come near me again…’ ‘There’s White Death in the Blackhouse, people think it’s you lot…’ Upon the Seventeenth Day of May They call it Dark Canadee Don’t ask me, don’t ask me I can’t tell you why they do For I don’t know me from you And I don’t know you from me Poor Pirate Max of Canadee But if you ask me what goes down At the Junction at the north of town I. I what. I stand beneath my lantern on the wharf at Canadee. I’m trying to recite my ballad as night falls, but I never get past there. But if you ask me what goes down At the Junction at the north of town I. -

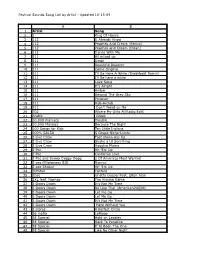

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive A Change is Gonna Come: The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies And Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of Masters of Laws in the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Kurt Dahl © Copyright Kurt Dahl, September 2009. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Dean of the College of Law University of Saskatchewan 15 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A6 i ABSTRACT The purpose of my research is to examine the music industry from both the perspective of a musician and a lawyer, and draw real conclusions regarding where the music industry is heading in the 21st century. -

Mingus, Nietzschean Aesthetics, and Mental Theater

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 16, No. 3 (2020) Music Performativity in the Album: Charles Mingus, Nietzschean Aesthetics, and Mental Theater David Landes This article analyzes a canonical jazz album through Nietzschean and perfor- mance studies concepts, illuminating the album as a case study of multiple per- formativities. I analyze Charles Mingus’ The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady as performing classical theater across the album’s images, texts, and music, and as a performance to be constructed in audiences’ minds as the sounds, texts, and visuals never simultaneously meet in the same space. Drawing upon Nie- tzschean aesthetics, I suggest how this performative space operates as “mental the- ater,” hybridizing diverse traditions and configuring distinct dynamics of aesthetic possibility. In this crossroads of jazz traditions, theater traditions, and the album format, Mingus exhibits an artistry between performing the album itself as im- agined drama stage and between crafting this space’s Apollonian/Dionysian in- terplay in a performative understanding of aesthetics, sound, and embodiment. This case study progresses several agendas in performance studies involving music performativity, the concept of performance complex, the Dionysian, and the album as a site of performative space. When Charlie Parker said “If you don't live it, it won't come out of your horn” (Reisner 27), he captured a performativity inherent to jazz music: one is lim- ited to what one has lived. To perform jazz is to make yourself per (through) form (semblance, image, likeness). Improvising jazz means more than choos- ing which notes to play. It means steering through an infinity of choices to craft a self made out of sound. -

A Remix Manifesto

An Educational Guide About The Film In RiP: A remix manifesto, web activist and filmmaker Brett Gaylor explores issues of copyright in the information age, mashing up the media landscape of the 20th century and shattering the wall between users and producers. The film’s central protagonist is Girl Talk, a mash‐up musician topping the charts with his sample‐based songs. But is Girl Talk a paragon of people power or the Pied Piper of piracy? Creative Commons founder, Lawrence Lessig, Brazil’s Minister of Culture, Gilberto Gil, and pop culture critic Cory Doctorow also come along for the ride. This is a participatory media experiment from day one, in which Brett shares his raw footage at opensourcecinema.org for anyone to remix. This movie‐as‐mash‐up method allows these remixes to become an integral part of the film. With RiP: A remix manifesto, Gaylor and Girl Talk sound an urgent alarm and draw the lines of battle. Which side of the ideas war are you on? About The Guide While the film is best viewed in its entirety, the chapters have been summarized, and relevant discussion questions are provided for each. Many questions specifically relate to music or media studies but some are more general in nature. General questions may still be relevant to the arts, but cross over to social studies, law and current events. Selected resources are included at the end of the guide to help students with further research, and as references for material covered in the documentary. This guide was written and compiled by Adam Hodgins, a teacher of Music and Technology at Selwyn House School in Montreal, Quebec. -

Rap and Feng Shui: on Ass Politics, Cultural Studies, and the Timbaland Sound

Chapter 25 Rap and Feng Shui: On Ass Politics, Cultural Studies, and the Timbaland Sound Jason King ? (body and soul ± a beginning . Buttocks date from remotest antiquity. They appeared when men conceived the idea of standing up on their hind legs and remaining there ± a crucial moment in our evolution since the buttock muscles then underwent considerable development . At the same time their hands were freed and the engagement of the skull on the spinal column was modified, which allowed the brain to develop. Let us remember this interesting idea: man's buttocks were possibly, in some way, responsible for the early emergence of his brain. Jean-Luc Hennig the starting point for this essayis the black ass. (buttocks, behind, rump, arse, derriere ± what you will) like mymother would tell me ± get your black ass in here! The vulgar ass, the sanctified ass. The black ass ± whipped, chained, beaten, punished, set free. territorialized, stolen, sexualized, exercised. the ass ± a marker of racial identity, a stereotype, property, possession. pleasure/terror. liberation/ entrapment.1 the ass ± entrance, exit. revolving door. hottentot venus. abner louima. jiggly, scrawny. protrusion/orifice.2 penetrable/impenetrable. masculine/feminine. waste, shit, excess. the sublime, beautiful. round, circular, (w)hole. The ass (w)hole) ± wholeness, hol(e)y-ness. the seat of the soul. the funky black ass.3 the black ass (is a) (as a) drum. The ass is a highlycontested and deeplyambivalent site/sight . It maybe a nexus, even, for the unfolding of contemporaryculture and politics. It becomes useful to think about the ass in terms of metaphor ± the ass, and the asshole, as the ``dirty'' (open) secret, the entrance and the exit, the back door of cultural and sexual politics. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1970S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1970s Page 130 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1970 25 Or 6 To 4 Everything Is Beautiful Lady D’Arbanville Chicago Ray Stevens Cat Stevens Abraham, Martin And John Farewell Is A Lonely Sound Leavin’ On A Jet Plane Marvin Gaye Jimmy Ruffin Peter Paul & Mary Ain’t No Mountain Gimme Dat Ding Let It Be High Enough The Pipkins The Beatles Diana Ross Give Me Just A Let’s Work Together All I Have To Do Is Dream Little More Time Canned Heat Bobbie Gentry Chairmen Of The Board Lola & Glen Campbell Goodbye Sam Hello The Kinks All Kinds Of Everything Samantha Love Grows (Where Dana Cliff Richard My Rosemary Grows) All Right Now Groovin’ With Mr Bloe Edison Lighthouse Free Mr Bloe Love Is Life Back Home Honey Come Back Hot Chocolate England World Cup Squad Glen Campbell Love Like A Man Ball Of Confusion House Of The Rising Sun Ten Years After (That’s What The Frijid Pink Love Of The World Is Today) I Don’t Believe In If Anymore Common People The Temptations Roger Whittaker Nicky Thomas Band Of Gold I Hear You Knocking Make It With You Freda Payne Dave Edmunds Bread Big Yellow Taxi I Want You Back Mama Told Me Joni Mitchell The Jackson Five (Not To Come) Black Night Three Dog Night I’ll Say Forever My Love Deep Purple Jimmy Ruffin Me And My Life Bridge Over Troubled Water The Tremeloes In The Summertime Simon & Garfunkel Mungo Jerry Melting Pot Can’t Help Falling In Love Blue Mink Indian Reservation Andy Williams Don Fardon Montego Bay Close To You Bobby Bloom Instant Karma The Carpenters John Lennon & Yoko Ono With My -

Jeezy All There Mp3 Download

Jeezy all there mp3 download Continue :Gaana Albums English Albums Source:2,source_id:1781965.object_type:2,id:1781965,status:0,title:All there,trackcount:1,track_ids:20634275 Objtype:2,share_url:/album/all-there,album: artist: artist_id:12643, name:Jizi,ar_click_url:/artist/jizi, ArtistAll اﻟﻘﺎﺋﻤﺔ اﻟﺼﻔﺤﺔ اﻟﺮﺋﻴﺴﻴﺔ أﻏﺎﻧﻲ ﺟﺪﻳﺪة اﺗﺼﺎل artist_id:12643,name:Jizi,ar_click_url:/artist/jizi,artist_id:696808, title:Bankroll Fresh, ar_click_url:/artist/bankroll-fresh,premium_content:0.release_date:Oct 08, 2016, 03:18,Language:English - Album Is Inactive All That Is An English Album, released in October 2016. All There Album has one song performed by Jeezy, Bankroll Fresh. Listen to all the songs there in high quality and download all there song on Gaana.com Related Tags - All There, All There Songs Download, Download All There Songs, Listen to All There Songs, All There MP3 Songs, Jeezy Songs Bankroll Fresh All There Free mp3 download and stream. The songs we share are not taken from websites or other media, we don't store mp3 files of new songs on our server, but we take them from YouTube to do so. Jeezy All There Ft Bankroll Fresh mp3 high quality download on MusicEels. Choose from multiple sources of music. A commentary in the genre of hip-hop from Kevin a a A Jerichos Revenge Fight to pull up make sure that yall there comment Simon AKERMAN LIT. Comment by Charles Sanchez 12 R.I.P. MIGUEL VARGAS Comment by Elijah Kramer Automatic I don't need a clue in this Comment Bloody Bird all there ̧x8F ̄ Michael Rainford's comment is all there all ̄ Comment by Curtis Madden and Comment by Chris Smither hot cheeto that I snack on.. -

BOARDWALK EMPIRE "In God We Trust" by Reginald Beltran Based

BOARDWALK EMPIRE "In God We Trust" By Reginald Beltran Based on characters by Terence Winter Reginald Beltran [email protected] FADE IN: EXT. FOREST - DAY A DEAD DOE lies on the floor. Blood oozes out of a fatal bullet wound on its side. Its open, unblinking eyes stare ahead. The rustling sound of leaves. The fresh blood attracts the attention of a hungry BEAR. It approaches the lifeless doe, and claims the kill for itself. The bear licks the fresh blood on the ground. More rustling of the undergrowth. The bear looks up and sees RICHARD HARROW, armed with a rifle, pushing past a thicket of trees and branches. For a moment, the two experienced killers stare at each other with unblinking eyes. One set belongs to a primal predator and the other set is half man, half mask. The bear stands on its two feet. It ROARS at its competitor. Richard readies his rifle for a shot, but the rifle is jammed. The bear charges. Calmly, Richard drops to one knee, examines the rifle and fixes the jam. He doesn’t miss a beat. He steadies the rifle and aims it. BANG! It’s a sniper’s mark. The bear drops to the ground immediately with a sickening THUD. Blood oozes out of a gunshot wound just under its eyes - the Richard Harrow special. EXT. FOREST - NIGHT Even with a full moon, light is sparse in these woods. Only a campfire provide sufficient light and warmth for Richard. A spit has been prepared over the fire. A skinned and gutted doe lies beside the campfire. -

MIC Buzz Magazine Article 10402 Reference Table1 Cuba Watch 040517 Cuban Music Is Caribbean Music Not Latin Music 15.Numbers

Reference Information Table 1 (Updated 5th June 2017) For: Article 10402 | Cuba Watch NB: All content and featured images copyrights 04/05/2017 reserved to MIC Buzz Limited content and image providers and also content and image owners. Title: Cuban Music Is Caribbean Music, Not Latin Music. Item Subject Date and Timeline Name and Topic Nationality Document / information Website references / Origins 1 Danzon Mambo Creator 1938 -- One of his Orestes Lopez Cuban Born n Havana on December 29, 1911 Artist Biography by Max Salazar compositions, was It is known the world over in that it was Orestes Lopez, Arcano's celloist and (Celloist and pianist) broadcast by Arcaño pianist who invented the Danzon Mambo in 1938. Orestes's brother, bassist http://www.allmusic.com/artist/antonio-arcaño- in 1938, was a Israel "Cachao" Lopez, wrote the arrangements which enables Arcano Y Sus mn0001534741/biography Maravillas to enjoy world-wide recognition. Arcano and Cachao are alive. rhythmic danzón Orestes died December 1991 in Havana. And also: entitled ‘Mambo’ In 29 August 1908, Havana, Cuba. As a child López studied several instruments, including piano and cello, and he was briefly with a local symphony orchestra. His Artist Biography by allmusic.com brother, Israel ‘Cachao’ López, also became a musician and influential composer. From the late 20s onwards, López played with charanga bands such as that led by http://www.allmusic.com/artist/orestes-lopez- Miguel Vásquez and he also led and co-led bands. In 1937 he joined Antonio mn0000485432 Arcaño’s band, Sus Maravillas. Playing piano, cello and bass, López also wrote many arrangements in addition to composing some original music.