Early Attempts at Settlement in the Northern Territory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Member for Wakefield South Australia

Conference delegates 2016 *Asterisks identify the recipients of the 2016 Crawford Fund Conference Scholarships ACHITEI, Simona Scope Global ALDERS, Robyn The University of Sydney ANDERSON AO, John The Crawford Fund NSW ANDREW AO, Neil Murray-Darling Basin Authority ANGUS, John CSIRO Agriculture *ARIF, Shumaila Charles Sturt University ARMSTRONG, Tristan Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade ASH, Gavin University of Southern Queensland ASTORGA, Miriam Western Sydney University AUGUSTIN, Mary Ann CSIRO *BAHAR, Nur The Australian National University BAILLIE, Craig The National Centre for Engineering in Agriculture (NCEA), University of Southern Queensland *BAJWA, Ali School of Agriculture & Food Sciences, The University of Queensland BARLASS, Martin Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre BASFORD, Kaye The Crawford Fund *BEER, Sally University of New England, NSW *BENYAM, Addisalem Central Queensland University BERRY, Sarah James Cook University / CSIRO *BEST, Talitha Central Queensland University BIE, Elizabeth Australian Government Department of Agriculture & Water Resources BISHOP, Joshua WWF-Australia BLACKALl, Patrick The University of Queensland *BLAKE, Sara South Australian Research & Development Institute (SARDI), Primary Industries & Regions South Australia BLIGHT AO, Denis The Crawford Fund *BONIS-PROFUMO, Gianna Charles Darwin University BOREVITZ, Justin The Australian National University BOYD, David The University of Sydney BRASSIL, Semih Western Sydney University BROGAN, Abigail Australian Centre -

Adelaide Coastal Waters Information Sheet No. 3

Adelaide Coastal Waters Information Sheet No. 3 Changes in urban environments Issued August 2009 EPA 769/09: This information sheet is part of a series of Fact Sheets on the Adelaide coastal waters and the findings of the Adelaide Coastal Waters Study (ACWS). Introduction Since European settlement in the 1830s, the Adelaide plains and Adelaide’s coastal environment have been subject to considerable change and pressure from a continually increasing population. In recent years there has been growing community concern about the effects of coastal and catchment development on the marine environment. Increases in stormwater flows and waste from wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) have also been of concern. Nutrients and other pollutants introduced to Adelaide’s nearshore waters from urban and rural runoff, WWTPs and some industrial sources have been found by the Adelaide Coastal Waters Study (ACWS) to have had a negative impact on Adelaide’s nearshore marine environment, including the loss of over 5,000 hectares of seagrass. Historical catchment changes When Adelaide was selected by Colonel William Light for South Australia’s state capital in 1836 there was a wide belt of coastal dunes and wide sandy beaches stretching to the north and south of Glenelg. From Seacliff to Outer Harbor there was a 30 km stretch of sand dunes broken only by the Patawalonga Creek at Glenelg. The Torrens River flowed into a series of swamps lying behind the coastal dunes and drained both north and south to the sea through the Patawalonga Creek and Port River system. The stretch of sand dunes comprised two or more parallel ridges each about 70 to 100 metres wide separated by narrow depressions or swales, consequently very little surface catchment runoff would have reached the coastline. -

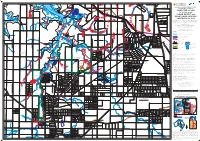

FLOOD EXTENT and PEAK FLOOD SURFACE CONTOURS for 2100

707500E 710000E 712500E 715000E 717500E 720000E 722500E 725000E 11 1 0 2 26 23 18 Middle Arm Road 19 22 BLACKMORE 17 19 27 25 18 1 NOONAMAH 2 19 ELIZABETH and BLACKMORE RIVER 23 3 5 24 20 CATCHMENTS — Sheet 2 25 4 20 4 COMPUTED 1% AEP RIVER 3 Aquiculture Farm Ponds 26 26 21 21 22 (1 in 100 year) 5 Middle Arm Boat Ramp 25 6 24 7 1 23 FLOOD EXTENT and 2 8 22 16 14 18 23 22 9 15 20 13 21 PEAK FLOOD SURFACE 24 10 1 19 12 17 20 23 CONTOURS for 2100 1 3 4 18 25 6 11 21 24 This map shows the Q100 flood and floodway extents caused by a 1% Annual 1.5 10 2 19 1.25 5 Exceedance Probability (AEP) Flood event over the Elizabeth and Blackmore 8600000N 8600000N 1.25 2 25 Keleson Road River Catchments. The extent of flooding shown on this map is indicative only, 17 Middle Arm Road 2 2 Strauss Field 26 hence, approximate. This map is available for sale from: 3 1.5 9 26 3 27 Land Information Centre, 1 1 8 27 3 1 2 Department of Lands, Planning and the Environment 3 1 3 7 16 1.5 1 3rd Floor NAB House, 71 Smith Street, Darwin, Northern Territory, 0800 28 29 29 Finn Road Finn 1.25 T: (08) 8995 5300 Email: [email protected] 6 30 2 28 31 GPO Box 1680, Darwin, Northern Territory, 0801. 3 31 15 4 5 14 27 33 This map is also available online at: 7 32 30 RIVER 6 7 8 10 35 www.nt.gov.au/floods http://nrmaps.nt.gov.au 9 13 11 12 8 26 32 Legend 2.5 4 5 25 34 3 24 6 Flood extent 3 7 24 8 23 Floodway, depth >2 metres (or velocity x depth > 1) 9 23 22 3 1.25 10 Peak flood surface contour, metres AHD 3 22 10.5 21 Creek channel / flow direction 21 20 Limit of flood mapping -

Inbound Flights Into Adelaide Sydney to Adelaide

INBOUND FLIGHTS INTO ADELAIDE SYDNEY TO ADELAIDE DATE AIRLINE FLIGHT NUMBER DEPARTURE CITY DEPARTURE TIME ARRIVAL CITY ARRIVAL TIME 11 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ762 SYDNEY 0700 ADELAIDE 0835 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF1555 SYDNEY 0815 ADELAIDE 0955 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA412 SYDNEY 0840 ADELAIDE 1020 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF741 SYDNEY 1045 ADELAIDE 1220 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF751 SYDNEY 1235 ADELAIDE 1410 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA418 SYDNEY 1240 ADELAIDE 1420 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF759 SYDNEY 1355 ADELAIDE 1530 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF761 SYDNEY 1510 ADELAIDE 1645 11 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ764 SYDNEY 1530 ADELAIDE 1705 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA428 SYDNEY 1610 ADELAIDE 1750 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF765 SYDNEY 1640 ADELAIDE 1815 11 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ768 SYDNEY 1725 ADELAIDE 1900 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF743 SYDNEY 1815 ADELAIDE 1950 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA436 SYDNEY 1815 ADELAIDE 1955 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF783 SYDNEY 1955 ADELAIDE 2130 11 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ770 SYDNEY 2015 ADELAIDE 2150 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA444 SYDNEY 2015 ADELAIDE 2155 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF785 SYDNEY 2035 ADELAIDE 2210 DATE AIRLINE FLIGHT NUMBER DEPARTURE CITY DEPARTURE TIME ARRIVAL CITY ARRIVAL TIME 12 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA403 SYDNEY 0645 ADELAIDE 0825 12 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ762 SYDNEY 0700 ADELAIDE 0835 12 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF735 SYDNEY 0705 ADELAIDE 0840 12 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF739 SYDNEY 0820 ADELAIDE 0955 12 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA412 SYDNEY 0840 ADELAIDE 1020 12 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ766 SYDNEY 1025 ADELAIDE 1200 12 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF741 SYDNEY 1045 ADELAIDE 1220 12 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF1557 SYDNEY 1130 ADELAIDE 1310 For any queries -

E–Muster Central Coast Family History Society Inc

The Official Journal of the Central Coast Family History Society Inc. E–Muster Central Coast Family History Society Inc. August 2020 Issue 27 The Official Journal of the Central Coast Family History Society Inc. Central Coast Family History Society Inc. PATRONS Lucy Wicks, MP Federal Member for Robertson Lisa Matthews, Mayor-Central Coast Chris Holstein, Deputy Mayor-Central Coast Members of NSW & ACT Association of Family History Societies Inc. (State Body) Australian Federation of Family History Organisation (National Body) Federation of Family History Societies, United Kingdom (International Body) Associate Member, Royal Australian Historical Society of NSW. Executive: President: Paul Schipp Vice President: Vacant Secretary: Vacant Treasurer: Ken Clark Public Officer: Marlene Bailey Committee: Bennie Campbell, Lorna Cullen, Carol Evans, Robyn Grant, Rachel Legge, Anthony Lehner, Trish Michael. RESEARCH CENTRE Building 4, 8 Russell Drysdale Street, EAST GOSFORD NSW 2250 Phone: 4324 5164 - Email [email protected] Open: Tues to Fri 9.30am-2.00pm; Thursday evening 6.00pm-9.30pm First Saturday of the month 9.30am-12noon Research Centre Closed on Mondays for Administration MEETINGS First Saturday of each month from February to November Commencing at 1.00pm – doors open 12.00 noon Research Centre opens from 9.30am Venue: Gosford Lions Community Hall Rear of 8 Russell Drysdale Street, EAST GOSFORD NSW The E-Muster The e- Muster is the Official August 2020 – No: 27 Journal of the Central Coast Family History Society Inc. The Muster it was first published in April 1983. REGULAR FEATURES The new e-Muster is published to our website Editorial .......................................................................... 4 3 times a year - April, President’s Piece ........................................................ -

AUSTRALIA DAY HOMEWORK CONTRACT – Week 1

HOMEWORK CONTRACT – Week 1 Write your spelling words each day using LOOK – SAY – COVER – WRITE - CHECK Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday AUSTRALIA DAY On the 26th January 1788, Captain Arthur 1) When is Australia Day ? Phillip and the First Fleet arrived at Sydney ______________________________________ Cove. The 26th January is celebrated each 2) Why do we celebrate Australia Day? year as Australia Day. This day is a public ______________________________________ holiday. There are many public celebrations to take part in around the country on 3) What ceremonies take place on Australia Day? Australia Day. Citizenship ceremonies take ______________________________________ place on Australia Day as well as the 4) What are the Australian of the Year and the presentation of the Order of Australia and Order of Australia awarded for? Australian of the Year awards for ______________________________________ outstanding achievement. It is a day of 5) Name this year’s Australian of the Year. great national pride for all Australians. ______________________________________ Correct the following paragraph. Write the following words in Add punctuation. alphabetical order. Read to see if it sounds right. Australia __________________ our family decided to spend australia day at the flag __________________ beach it was a beautiful sunny day and the citizenship __________________ celebrations __________________ beach was crowded look at all the australian ceremonies __________________ flags I said. I had asked my parents to buy me Australian __________________ a towel with the australian flag on it but the First Fleet __________________ shop had sold out awards __________________ Circle the item in each row that WAS NOT invented by Australians. boomerang wheel woomera didgeridoo the Ute lawn mower Hills Hoist can opener Coca-Cola the bionic ear Blackbox Flight Recorder Vegemite ©TeachThis.com.au HOMEWORK CONTRACT – Week 1 Created by TeachThis.com.au Number Facts Problem solving x 4 3 5 9 11 1. -

Sorry Day Is a Day Where We Remember the Stolen Generations

Aboriginal Heritage Office Yarnuping Education Series Ku-ring-gai, Lane Cove, North Sydney, Northern Beaches, Strathfield and Willoughby Councils © Copyright Aboriginal Heritage Office www.aboriginalheritage.org Yarnuping 5 Sorry Day 26th May 2020 Karen Smith Education Officer Sorry Day is a day where we remember the Stolen Generations. Protection & Assimilation Policies Have communities survived the removal of children? The systematic removal and cultural genocide of children has an intergenerational, devastating effect on families and communities. Even Aboriginal people put into the Reserves and Missions under the Protectionist Policies would hide their children in swamps or logs. Families and communities would colour their faces to make them darker. Not that long after the First Fleet arrived in 1788, a large community of mixed ancestry children could be found in Sydney. They were named ‘Friday’, ‘Johnny’, ‘Betty’, and denied by their white fathers. Below is a writing by David Collins who witnessed this occurring: “The venereal disease also has got among them, but I fear our people have to answer for that, for though I believe none of our women had connection with them, yet there is no doubt that several of the Black women had not scrupled to connect themselves with the white men. Of the certainty of this extraordinary instance occurred. A native woman had a child by one of our people. On its coming into the world she perceived a difference in its colour, for which not knowing how to account, she endeavoured to supply by art what she found deficient in nature, and actually held the poor babe, repeatedly over the smoke of her fire, and rubbed its little body with ashes and dirt, to restore it to the hue with which her other children has been born. -

Journal of a Voyage Around Arnhem Land in 1875

JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE AROUND ARNHEM LAND IN 1875 C.C. Macknight The journal published here describes a voyage from Palmerston (Darwin) to Blue Mud Bay on the western shore of the Gulf of Carpentaria, and back again, undertaken between September and December 1875. In itself, the expedition is of only passing interest, but the journal is worth publishing for its many references to Aborigines, and especially for the picture that emerges of the results of contact with Macassan trepangers along this extensive stretch of coast. Better than any other early source, it illustrates the highly variable conditions of communication and conflict between the several groups of people in the area. Some Aborigines were accustomed to travelling and working with Macassans and, as the author notes towards the end of his account, Aboriginal culture and society were extensively influenced by this contact. He also comments on situations of conflict.1 Relations with Europeans and other Aborigines were similarly complicated and uncertain, as appears in several instances. Nineteenth century accounts of the eastern parts of Arnhem Land, in particular, are few enough anyway to give another value. Flinders in 1802-03 had confirmed the general indications of the coast available from earlier Dutch voyages and provided a chart of sufficient accuracy for general navigation, but his contact with Aborigines was relatively slight and rather unhappy. Phillip Parker King continued Flinders' charting westwards from about Elcho Island in 1818-19. The three early British settlements, Fort Dundas on Melville Island (1824-29), Fort Wellington in Raffles Bay (1827-29) and Victoria in Port Essington (1838-49), were all in locations surveyed by King and neither the settlement garrisons nor the several hydrographic expeditions that called had any contact with eastern Arnhem Land, except indirectly by way of the Macassans. -

Intermediate a New Life Australia Worksheet 8: the First Fleet

Intermediate A New Life Australia Worksheet 8: The First Fleet Copyright With the exception of the images contained in this document, this work is © Commonwealth of Australia 2011. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only for your personal, non- commercial use or use within your organisation for the purposes of the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP). Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Use of all or part of this material must include the following attribution: © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 This document must be attributed as [Intermediate A New Life Australia – Worksheet 8: The First Fleet]. Any enquiries concerning the use of this material should be directed to: The Copyright Officer Department of Education and Training Location code C50MA10 GPO Box 9880 Canberra ACT 2601 or emailed to [email protected]. Images ©2011 Photos.com, a division of Getty Images. All rights reserved. Images reproduced with permission. Acknowledgements The AMEP is funded by the Australian Government Department of Education and Training. Disclaimer While the Department of Education and Training and its contributors have attempted to ensure the material in this booklet is accurate at the time of release, the booklet contains material on a range of matters that are subject to regular change. No liability for negligence or otherwise is assumed by the department or its contributors should anyone suffer a loss or damage as a result of relying on the information provided in this booklet. References to external websites are provided for the reader’s convenience and do not constitute endorsement of the information at those sites or any associated organisation, product or service. -

Historical Earthquakes in Western Australia Kevin Mccue Australian Seismological Centre, Canberra ACT

Historical Earthquakes in Western Australia Kevin McCue Australian Seismological Centre, Canberra ACT. Abstract This paper is a tabulation and description of some earthquakes and tsunamis in Western Australia that occurred before the first modern short-period seismograph installation at Watheroo in 1958. The purpose of investigating these historical earthquakes is to better assess the relative earthquake hazard facing the State than would be obtained using just data from the post–modern instrumental period. This study supplements the earlier extensive historical investigation of Everingham and Tilbury (1972). It was made possible by the Australian National library project, TROVE, to scan and make available on-line Australian newspapers published before 1954. The West Australian newspaper commenced publication in Perth in 1833. Western Australia is rather large with a sparsely distributed population, most of the people live along the coast. When an earthquake is felt in several places it would indicate a larger magnitude than one in say Victoria felt at a similar number of sites. Both large interplate and local intraplate earthquakes are felt in the north-west and sometimes it is difficult to identify the source because not all major historical earthquakes on the plate boundary are tabulated by the ISC or USGS. An earthquake on 29 April 1936 is a good example, local or distant source? An interesting feature of the large earthquakes in WA is their apparent spatial and temporal migration, the latter alluded to by Everingham and Tilbury (1972). One could deduce that the seismicity rate changed before the major earthquake in 1906 offshore the central west coast of WA. -

5 Potential Impacts and Mitigation – Water Quality

5 POTENTIAL IMPACTS AND MITIGATION – WATER QUALITY The approach adopted for this study to evaluate potential water quality impacts associated with the proposed discharge relied on the application and interpretation of calibrated far-field, two-dimensional hydrodynamic (HD) and advection dispersion (AD) modelling tool built using MIKE21. This modelling was supported, guided and informed by a range of data and other relevant information. These data, the work conducted, and key findings are presented below. 5.1 Numerical Modelling Numerical modelling was used to simulate the transport, dilution and dispersion of the proposed discharge at Gunn Point and surrounding waters. The proposed discharge was modelled (see Appendix A) as a conservative tracer. This allows the dilution and dispersion of the effluent to be understood. The numerical modelling, and therefore the modelled tracer concentrations, can be considered conservative for the following reasons: Biological and physical processes such as the deposition of particulate material or the take up of bioavailable nutrients or absorption by sediments and algal mats (microphytobenthos) growing on the sediments of the significant intertidal areas in and around Shoal Bay are not included in the modelling. Three-dimensional turbulent dispersion associated with wave action has not been included in the modelling. Because the model was very computationally demanding, all scenarios were undertaken in 2D. However, during the model calibration and sensitivity testing, 3D simulations were carried out to confirm the mixing processes were resolved appropriately. The strong tidal currents and shallow water mean the site is well mixed, and the 3D modelling did not provide significantly different results. 5.1.1 Simulation Scenarios The model was run for two separate years: June 2005 – May 2006 inclusive May 2016 to April 2016 inclusive Whilst tropical conditions are highly variable, 2005-2006 was considered a ‘typical’ wet season, and 2016- 2017 a season with higher than average rainfall. -

Mount Ommaney

Street Name Register Mount Ommaney Last updated : August 2020 MOUNT OMMANEY (established January 1970 – 3rd Centenary suburb) Originally named by Queensland Place Names Board on 1 July 1969. Name and boundaries confirmed by Minister for Survey and Valuation, Urban and Regional Affairs on 11 August 1975. Suburb The name is derived from hill feature, possibly named after John OMMANNEY, (1837-1856), nephew of Dr Stephen Simpson of Wolston House, OMMANNEY having been killed nearby in a fall from a horse. History Mount Ommaney was designed as a series of exclusive courts, many named after prominent Australian politicians and explorers, as well as artists from all genre of classical music. MOUNT OMMANEY A Abel Smith Crescent Sir Henry ABEL SMITH was Governor of Queensland 1958-1966 Archer Court ?? David ARCHER (1860-1900) was an explorer and botanist. In 1841 he took up Durandur Station in the Moreton district Arrabri Avenue Aboriginal word meaning “big mountain” (S.E. Endacott) renamed from Doonkuna (meaning ‘rising’) St., Jindalee in 1969 Augusta Circuit B Bartok Place Bela BARTOK (1881-1945) – Hungarian composer Beagle Place Name of an English ship used to survey the Australian coastline Becker Place Ludwig BECKER (?1808-1861) was an artist, explorer and naturalist Bedwell Place A surveyor on the survey ship ‘Pearl’ in the 1870s (BCC Archives) Bizet Close Georges BIZET (1838-1875) – French composer Blaxland Court Gregory BLAXLAND (1778-1853) was an explorer and pioneer farmer of Australia who in 1813 was in the first party to cross the Blue Mountains (NSW) in the Great Dividing Range Bondel Place Bounty Street Captain William Bligh’s ship ‘The Bounty’ Bowles Street After W L Bowles, a modern Australian sculptor Bowman Place Burke Court Robert O’Hara BURKE (1820-1861) and William WILLS in 1860 were the first explorers to cross Australia from south to north.