Adaptive Capacity for Climate Change in Maldivian Rural Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 STATE ELECTRIC COMPANY LIMITED TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary About us 1 Chairman’s Message 3 CEO’s Message 4 Board of Directors 5 Executive Management 7 How we grew 14 Who we serve 15 Statistical Highlights 16 Financial Highlights 17 Our Footprint 18 Market Review 19 Strategic Review 20 - Power Generation 20 - Distribution System 24 - Human Resources 25 - Corporate Social Responsibility 29 - Customer Services 30 - Financial Overview 32 - Creating efficiency and reducing cost 40 - Business Diversification 41 - Renewable Energy 44 Moving Forward 45 - Grid of the Future 46 - An Efficient Future 47 - Investing for the Future 47 Audited Financial Statements 2017 48 Company Contacts EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The year 2017 is marked as a challenging yet Business was diversified into new areas such successful year in the recent history of State as water bottling and supply. Further STELCO Electric Company Limited (STELCO). The main showroom services were expanded to provide highlight of the year is that STELCO has more varieties of products. observed a net positive growth, after a few consecutive loss making years. Though STELCO has posted a positive growth, the increasing gearing ratio is an area of Some of the success stories in 2017 include the concern which needs to be addressed at the commencement of STELCO Fifth Power policy level with government authorities. Development Project as well as addition of generation capacity to the STELCO network. Based on current forecasts, the electricity Further upgrades on distribution network as demand doubles every five to ten years, hence well as adoption of new technologies to STELCO needs to generate a profit of over MVR improve service quality were implemented. -

Population and Housing Census 2014

MALDIVES POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS 2014 National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’, Maldives 4 Population & Households: CENSUS 2014 © National Bureau of Statistics, 2015 Maldives - Population and Housing Census 2014 All rights of this work are reserved. No part may be printed or published without prior written permission from the publisher. Short excerpts from the publication may be reproduced for the purpose of research or review provided due acknowledgment is made. Published by: National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’ 20379 Republic of Maldives Tel: 334 9 200 / 33 9 473 / 334 9 474 Fax: 332 7 351 e-mail: [email protected] www.statisticsmaldives.gov.mv Cover and Layout design by: Aminath Mushfiqa Ibrahim Cover Photo Credits: UNFPA MALDIVES Printed by: National Bureau of Statistics Male’, Republic of Maldives National Bureau of Statistics 5 FOREWORD The Population and Housing Census of Maldives is the largest national statistical exercise and provide the most comprehensive source of information on population and households. Maldives has been conducting censuses since 1911 with the first modern census conducted in 1977. Censuses were conducted every five years since between 1985 and 2000. The 2005 census was delayed to 2006 due to tsunami of 2004, leaving a gap of 8 years between the last two censuses. The 2014 marks the 29th census conducted in the Maldives. Census provides a benchmark data for all demographic, economic and social statistics in the country to the smallest geographic level. Such information is vital for planning and evidence based decision-making. Census also provides a rich source of data for monitoring national and international development goals and initiatives. -

Table 2.3 : POPULATION by SEX and LOCALITY, 1985, 1990, 1995

Table 2.3 : POPULATION BY SEX AND LOCALITY, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000 , 2006 AND 2014 1985 1990 1995 2000 2006 20144_/ Locality Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Republic 180,088 93,482 86,606 213,215 109,336 103,879 244,814 124,622 120,192 270,101 137,200 132,901 298,968 151,459 147,509 324,920 158,842 166,078 Male' 45,874 25,897 19,977 55,130 30,150 24,980 62,519 33,506 29,013 74,069 38,559 35,510 103,693 51,992 51,701 129,381 64,443 64,938 Atolls 134,214 67,585 66,629 158,085 79,186 78,899 182,295 91,116 91,179 196,032 98,641 97,391 195,275 99,467 95,808 195,539 94,399 101,140 North Thiladhunmathi (HA) 9,899 4,759 5,140 12,031 5,773 6,258 13,676 6,525 7,151 14,161 6,637 7,524 13,495 6,311 7,184 12,939 5,876 7,063 Thuraakunu 360 185 175 425 230 195 449 220 229 412 190 222 347 150 197 393 181 212 Uligamu 236 127 109 281 143 138 379 214 165 326 156 170 267 119 148 367 170 197 Berinmadhoo 103 52 51 108 45 63 146 84 62 124 55 69 0 0 0 - - - Hathifushi 141 73 68 176 89 87 199 100 99 150 74 76 101 53 48 - - - Mulhadhoo 205 107 98 250 134 116 303 151 152 264 112 152 172 84 88 220 102 118 Hoarafushi 1,650 814 836 1,995 984 1,011 2,098 1,005 1,093 2,221 1,044 1,177 2,204 1,051 1,153 1,726 814 912 Ihavandhoo 1,181 582 599 1,540 762 778 1,860 913 947 2,062 965 1,097 2,447 1,209 1,238 2,461 1,181 1,280 Kelaa 920 440 480 1,094 548 546 1,225 590 635 1,196 583 613 1,200 527 673 1,037 454 583 Vashafaru 365 186 179 410 181 229 477 205 272 -

School Statistics 2013

SCHOOL STATISTICS 2013 MINISTRY OF EDUCATION Republic of Maldives FOREWORD Ministry of Education takes pleasure of presenting School Statistics 2013, to provide policymakers, educational planners, administrators, researchers and other stakeholders with suitable and effective statistical information. This publication is an integral part of the Educational Management Information System (EMIS) which is an essential source for quantitative educational data which reflects the improvement in educational policies and educational development in Maldives. We have been carefully and continuously collecting, analyzing, revising and updating the qualitative and quantitative data to make it as interpretive as possible, to ensure accuracy and reliability. We thank all who have contributed by providing the requested data to complete and make this publication a success. We thank the schools for their part in providing the data, the bodies within Ministry of Education for their tireless and valuable contribution and commitment in the preparation of the book, and also, the Department of National Planning (DNP) for providing us with the data on population. We hope that School Statistics 2013 will fulfill its objective of providing essential information to the education sector. SCHOOL STATISTICS 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages Pages INTRODUCTION 1 SECTION 3: TEACHERS SECTION 1: ENROLMENT TRENDS & ANALYSIS Teachers by employment status by gender 46 Student enrolment 2001 to 2011 by provider 2 - 3 SECTION 4: STUDENT & POPULATION AT ISLAND LEVEL Transition rate -

Energy Supply and Demand

Technical Report Energy Supply and Demand Fund for Danish Consultancy Services Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources Maldives Project INT/99/R11 – 02 MDV 1180 April 2003 Submitted by: In co-operation with: GasCon Project ref. no. INT/03/R11-02MDV 1180 Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources, Maldives Supply and Demand Report Map of Location Energy Consulting Network ApS * DTI * Tech-wise A/S * GasCon ApS Page 2 Date: 04-05-2004 File: C:\Documents and Settings\Morten Stobbe\Dokumenter\Energy Consulting Network\Løbende sager\1019-0303 Maldiverne, Renewable Energy\Rapporter\Hybrid system report\RE Maldives - Demand survey Report final.doc Project ref. no. INT/03/R11-02MDV 1180 Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources, Maldives Supply and Demand Report List of Abbreviations Abbreviation Full Meaning CDM Clean Development Mechanism CEN European Standardisation Body CHP Combined Heat and Power CO2 Carbon Dioxide (one of the so-called “green house gases”) COP Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention of Climate Change DEA Danish Energy Authority DK Denmark ECN Energy Consulting Network elec Electricity EU European Union EUR Euro FCB Fluidised Bed Combustion GDP Gross Domestic Product GHG Green house gas (principally CO2) HFO Heavy Fuel Oil IPP Independent Power Producer JI Joint Implementation Mt Million ton Mtoe Million ton oil equivalents MCST Ministry of Communication, Science and Technology MOAA Ministry of Atoll Administration MFT Ministry of Finance and Treasury MPND Ministry of National Planning and Development NCM Nordic Council of Ministers NGO Non-governmental organization PIN Project Identification Note PPP Public Private Partnership PDD Project Development Document PSC Project Steering Committee QA Quality Assurance R&D Research and Development RES Renewable Energy Sources STO State Trade Organisation STELCO State Electric Company Ltd. -

The Shark Fisheries of the Maldives

The Shark Fisheries of the Maldives A review by R.C. Anderson and Hudha Ahmed Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture, Republic of Maldives and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1993 Tuna fishing is the most important fisheries activity in the Maldives. Shark fishing is oneof the majorsecondary fishing activities. A large proportion of Maldivian fishermen fish for shark at least part-time, normally during seasons when the weather is calm and tuna scarce. Most shark products are exported, with export earnings in 1991 totalling MRf 12.1 million. There are three main shark fisheries. A deepwater vertical longline fishery for Gulper Shark (Kashi miyaru) which yields high-value oil for export. An offshore longline and handline fishery for oceanic shark, which yields fins andmeat for export. And an inshore gillnet, handline and longline fishery for reef and othe’r atoll-associated shark, which also yields fins and meat for export. The deepwater Gulper Shark stocks appear to be heavily fished, and would benefit from some control of fishing effort. The offshore oceanic shark fishery is small, compared to the size of the shark stocks, and could be expanded. The reef shark fisheries would probably run the risk of overfishing if expanded very much more. Reef shark fisheries are asource of conflict with the important tourism industry. ‘Shark- watching’ is a major activity among tourist divers. It is roughly estimated that shark- watching generates US $ 2.3 million per year in direct diving revenue. It is also roughly estimated that a Grey Reef Shark may be worth at least one hundred times more alive at a dive site than dead on a fishing boat. -

Waste Management

study of nationally recognized good practices of WASTE MANAGEMENT Case-study of AA.Ukulhas and B.Maalhos study of nationally recognized good practices of WASTE MANAGEMENT Case-study of AA.Ukulhas and B.Maalhos Prepared by: Aisha Niyaz © United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Mangroves for the Future (MFF) Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior permission from the copyright holder, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of the publication for resale or for other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 AIM OF THE STUDY ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

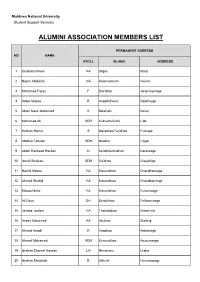

Alumini Association Members List

Maldives National University Student Support Services ALUMINI ASSOCIATION MEMBERS LIST PERMANENT ADDRESS NO NAME ATOLL ISLAND ADDRESS 1 Saudulla Idrees HA Uligan Maaz 2 Nazim Abdullah GA Kolamaafushi Veena 3 Mohamed Fayaz F Bile'dhoo Janavarymage 4 Adam Moosa R Angolhitheem Vaijeheyge 5 Abdul Nasir Mohamed K Maafushi Nares 6 Mohamed Ali HDH Kulhudhu'fushi Lido 7 Sulthan Ramiz S Maradhoo Feydhoo Finivage 8 Abdulla Fahudu GDH Nadella Lilyge 9 Abdul Rasheed Hassan N Kendhikulhudhoo Karankage 10 Ismail Shafeeu GDH Ga'dhoo Ulaajehige 11 Hamid Moosa HA Ihavandhoo Chandhaneege 12 Ahmed Shahid HA Ihavandhoo Chandhaneege 13 Moosa Mahir HA Ihavandhoo Funamaage 14 Ali Easa DH Bandidhoo Falhoamaage 15 Javaad Jaufaru HA Thakandhoo Greenvilla 16 Anees Mohamed AA Ukulhas Starling 17 Ahmed Asadh R Vaadhoo Anbareege 18 Ahmed Mohamed HDH Kumundhoo Asurumaage 19 Ibrahim Shareef Hassan LH Hinnavaru Uraha 20 Ibrahim Shaukath R Alifushi Heenamaage 21 Mahaz Ali Zahir GDH Madaveli Meyna 22 Hassan Zareer Ibrahim GA Kondey Lucky Sun 23 Mohamed Aslam HA Dhidhdhoo Aaliya 24 Mohamed Shukuree R Maduvvary Moonbeam 25 Aminath Adam LH Hinnavaru Feyrugasdhoshuge 26 Sheela Mufeed GN Fuahmulah Kuri 27 Thaifa Shaheed GDH Thinadhoo Tibet 28 Aminath Inasha GDH Thinadhoo Muringu 29 Shiuna Shiyam K Male' G.Happyside 30 Mariyam Shahma HDH Kurinbee Gulfaamuge 31 Samiya Abdul Mughunee GDH Ga'dhoo Beach Heaven 32 Azra Ibrahim V Felidhoo Peradais 33 Hudha Abdul Samadh R Hulhudhuffaaru Dhilhaazuge 34 Aminath Rasheedha R Hulhudhuffaaru Kashmeeruvadhee 35 Aishath Shimla GDH Vaadhoo Greenvilla -

List of Registered Pharmacies 2018, July

Maldives Food and Drug Authority Ministry Of Health Male', Republic of Maldives REGISTERED PHARMACY LIST JULY 2018 Number: MTG/RE-PL/Li 0007/2018-0007 Date: 09.07.2018 ATOLL / ISLAN NAME OF PHARMACY PHARMACY ADDRESS CODE REG NO EXPIRY DATE DATE OF REGISTER LICENCE RENEWED DATE PH-0058 QN K.MALE ADK PHARMACY 1 ADK HOSPITAL, SOSUNMAGU 28.08.2017 14.02.1996 27.08.2019 PH-0056 A K.MALE ADK PHARMACY 2 M. SNOWLIYAA ,KANBAA AISARANIHINGUN,MALE' 10.10.2017 08.12.2002 09.10.2019 PH-0057 A K.MALE ADK PHARMACY 3 H. VILLUNOO 21.09.2016 08.03.1994 20.09.2018 PH-0073 A K.MALE ADK PHARMACY 5 AROWMA VILLA , MAVEYOMAGU 15.05.2017 26.08.2010 14.05.2019 PH -0366 A K.MALE ADK PHARMACY 6 M. NOOASURUMAAGE , DHAKADHAA MAGU 27.08.2017 26.08.2010 26.08.2019 PH-0038 B K.MALE AMDC PHARMACY M.MISURUMAAGE , SHAARIUVARUDHEE HINGUN 08.03.2017 01.03.1994 07.03.2019 PH-0040 C K.MALE BALSAM PHARMACY 1 MA. TWILIGHT, ISKANDHARUMAGU 11.08.2016 11.08.2016 10.08.2018 PH-0039 D K.MALE CENTRAL CLINIC PHARMACY M. DHILLEE VILLA , JANBUMAGU 25.05.2017 15.10.2002 24.05.2019 PH-0356 D K.MALE CENTRAL MEDICAL CENTRE CHEMIST M. NIMSAA , FAREEDHEE MAGU 26.09.2017 12.07.2010 25.09.2019 PH - 0369 D K.MALE CENTRAL MEDICAL CENTRE PHARMACY M. NIMSAA , FAREEDHEE MAGU 26.09.2017 06.10.2010 25.09.2019 PH- 0071 E K.MALE CRESCENT PHARMACY G.HITHIFARU , MAJEEDHEE MAGU 27.03.2017 01.03.1994 26.03.2019 PH- 0089 EE K.MALE DR. -

Post-Tsunami Agricultural and Fisheries Rehabilitation Programme Project Performance Evaluation

Independent Office Independent Office of Evaluation of Evaluation Independent O ce of Evaluation Independent O ce of Evaluation International Fund for Agricultural Development International Fund for Agricultural Development Via Paolo di Dono, 44 - 00142 Rome, Italy Via Paolo di Dono, 44 - 00142 Rome, Italy Tel: +39 06 54591 - Fax: +39 06 5043463 Tel: +39 06 54591 - Fax: +39 06 5043463 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.ifad.org/evaluation www.ifad.org/evaluation www.twitter.com/IFADeval www.twitter.com/IFADeval Independent Office of Evaluation www.youtube.com/IFADevaluation www.youtube.com/IFADevaluation Independent Office Independent Office of Evaluation of Evaluation Independent O ce of Evaluation Independent O ce of Evaluation Republic of Maldives International Fund for Agricultural Development International Fund for Agricultural Development Post-Tsunami Agricultural and Fisheries Via Paolo di Dono, 44 - 00142 Rome, Italy Via Paolo di Dono, 44 - 00142 Rome, Italy Tel: +39 06 54591 - Fax: +39 06 5043463 Tel: +39 06 54591 - Fax: +39 06 5043463 Rehabilitation Programme E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.ifad.org/evaluation www.ifad.org/evaluation PROJECT PERFORMANCE EVALUATION www.twitter.com/IFADeval www.twitter.com/IFADeval www.youtube.com/IFADevaluation www.youtube.com/IFADevaluation Bureau indépendant Oficina de Evaluación de l’évaluation Independiente Bureau indépendant de l’évaluation Oficina de Evaluación Independiente Fonds international de développement agricole Fondo Internacional -

Pharmacy Register (December 2019)

Maldives Food and Drug Authority Ministry Of Health Male', Republic of Maldives PHARMACY REGISTER Number: MTG/RE-PL/Li 0007/2019-0012 Date: 31.12.2019 (December) ATOLL / ISLAN NAME OF PHARMACY PHARMACY ADDRESS PHARMACY OWNER NAME OWNER ADDRESS CODE REG NO EXPIRY DATEEXPIRY DATE REGISTER OF LICENCE RENEWED DATE PH-0058 QN K.MALE ADK PHARMACY 1 ADK HOSPITAL, SOSUNMAGU ADK PHARMACUITICAL COMPANY PVT H.SILVER LEAF 07.03.2019 14.02.1996 06.03.2021 PH-0056 A K.MALE ADK PHARMACY 2 M. SNOWLIYAA ,KANBAA AISARANIHINGUN,MALE' ADK COMPANY PVT LTD H.SILVER LEAF 08.10.2019 08.12.2002 07.10.2021 PH-0057 A K.MALE ADK PHARMACY 3 H. VILLUNOO ADK COMPANY PVT LTD H.SILVER LEAF 19.09.2018 08.03.1994 18.09.2020 PH-0073 A K.MALE ADK PHARMACY 5 AROWMA VILLA , MAVEYOMAGU ADK COMPANY PVT LTD H.SILVER LEAF 23.05.2019 26.08.2010 24.05.2021 PH -0366 A K.MALE ADK PHARMACY 6 M. VELIFERAM, HANDHUVAREE HINGUN ADK COMPANY PVT LTD H.SILVER LEAF 25.09.2018 26.08.2010 24.09.2020 PH-0038 B K.MALE AMDC PHARMACY M. RANALI , SHAARIUVARUDHEE HINGUN AMDC & DIGNOTIC CENTRE PVT LTD., M.MISURURUVAAGE 12.03.2019 01.03.1994 11.03.2021 PH-0039 D K.MALE CENTRAL CLINIC PHARMACY M. DHILLEE VILLA , JANBUMAGU CENTRAL CLINIC MEDICAL SERVICES PM. DHILLEEVILLA, JANBUMAGU 28.05.2019 15.10.2002 27.05.2021 PH-0356 D K.MALE CENTRAL MEDICAL CENTRE CHEMIST M. NIMSAA , FAREEDHEE MAGU CENTRAL CLINIC MEDICAL SERVICES PM.DHIHLEEVILLA, K.MALE' 25.09.2019 12.07.2010 24.09.2021 PH - 0369 D K.MALE CENTRAL MEDICAL CENTRE PHARMACY M. -

Adaptive Capacity of Islands of the Maldives to Climate Change

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following work: Mohamed, Ibrahim (2018) Adaptive capacity of islands of the Maldives to climate change. PhD Thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: https://doi.org/10.25903/fnym%2Dnr79 Copyright © 2018 Ibrahim Mohamed. The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owners of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please email [email protected] Adaptive Capacity of Islands of the Maldives to Climate Change Ibrahim Mohamed Master of Applied Science in Protected Area Management Bachelor of Science (Biology and Chemistry) A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the James Cook University in November 2018 College of Science and Engineering To my love, Aisha, and our island princess, Balqees i Acknowledgements To my dearest love, Aisha, for the love and inspiration, for all the tears and long waits, for being my companion and for always being patient. Thank you for sacrificing so much and giving me unconditional love, and sincere support and prayers throughout this journey. NO words can thank you enough. For my loving daughter, Balqees, who made life enjoyable even during the hardest times. The hugs when I leave to go to University and the waiting for bed time stories made every day special. I hope you will soon understand why Daddy needed to spend a lot of time at Uni. I would like to thank the communities of Ukulhas, Bodufolhudhoo, Hanimaadhoo, Vilufushi and Fuvahmulah islands, and the people who took part in my research and assisted in many ways.