Download Preprint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Allure Seen Through a Screen

22 | Thursday, July 25, 2019 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY LIFE Ancient allure seen through a screen The popularity of a recent online Popular tour sites drama staged in Top scenic areas in Xi’an in the Tang Dynasty summer 1. Emperor Qinshihuang’s has translated into Mausoleum Site Museum a surge of visitors 2. Xi’an City Walls 3. Tang Paradise Theme Park to Xi’an, 4. Shaanxi History Museum 5. Muslim Street Xu Lin reports. 6. Huaqing Palace 7. North Square of Giant Wild he hit thriller series, The Goose Pagoda Longest Day in Chang’an, 8. Daming Palace National takes viewers to the heyday Heritage Park of the Tang Dynasty (618 9. Yongxing Fang T907). And since its premiere on June 10. Sleepless City of Tang 27, it has been creating a new heyday for Xi’an’s travel sector and interest SOURCE: MAFENGWO in its past. In the online drama, a deathrow Top domestic filming spots as inmate, played by actor Lei Jiayin, summer destinations accepts a mission from a govern 1. Xi’an, Shaanxi province ment official, played by singeractor 2. Suzhou, Jiangsu province Yi Yangqianxi, during Lantern Festi 3. Chongqing val. The condemned criminal must 4. Zhangjiajie, Hunan province save the national capital, Chang’an, 5. Nanjing, Jiangsu province from a secret enemy attack within 24 6. Shanghai hours. Chang’an is today Shaanxi’s 7. Qingdao, Shandong province provincial capital, Xi’an. 8. Dongyang, Zhejiang province The show’s extreme popularity 9. Bayanbulak Grassland, Xinji has intensified interest in travel to ang Uygur autonomous region Xi’an. -

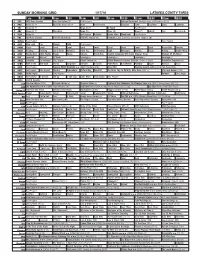

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Wisconsin. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Clangers Luna! LazyTown Luna! LazyTown 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Liberty Paid Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Seattle Seahawks at Carolina Panthers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Soulful Symphony With Darin Atwater: Song Motown 25 My Music 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Race to Witch Mountain ›› (2009, Aventura) (PG) Zona NBA Treasure Guards (2011) Anna Friel, Raoul Bova. -

0Ca60ed30ebe5571e9c604b661

Mark Parascandola ONCE UPON A TIME IN SHANGHAI Cofounders: Taj Forer and Michael Itkoff Creative Director: Ursula Damm Copy Editors: Nancy Hubbard, Barbara Richard © 2019 Daylight Community Arts Foundation Photographs and text © 2019 by Mark Parascandola Once Upon a Time in Shanghai and Notes on the Locations © 2019 by Mark Parascandola Once Upon a Time in Shanghai: Images of a Film Industry in Transition © 2019 by Michael Berry All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-942084-74-7 Printed by OFSET YAPIMEVI, Istanbul No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of copyright holders and of the publisher. Daylight Books E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.daylightbooks.org 4 5 ONCE UPON A TIME IN SHANGHAI: IMAGES OF A FILM INDUSTRY IN TRANSITION Michael Berry THE SOCIALIST PERIOD Once upon a time, the Chinese film industry was a state-run affair. From the late centers, even more screenings took place in auditoriums of various “work units,” 1940s well into the 1980s, Chinese cinema represented the epitome of “national as well as open air screenings in many rural areas. Admission was often free and cinema.” Films were produced by one of a handful of state-owned film studios— tickets were distributed to employees of various hospitals, factories, schools, and Changchun Film Studio, Beijing Film Studio, Shanghai Film Studio, Xi’an Film other work units. While these films were an important part of popular culture Studio, etc.—and the resulting films were dubbed in pitch-perfect Mandarin during the height of the socialist period, film was also a powerful tool for education Chinese, shot entirely on location in China by a local cast and crew, and produced and propaganda—in fact, one could argue that from 1949 (the founding of the almost exclusively for mainland Chinese film audiences. -

Hengten Networks (00136.HK)

22-Feb-2021 ︱Research Department HengTen Networks (00136.HK) SBI China Capital Research Department T: +852 2533 3700 Initiation: China’s Netflix backed by Evergrande and Tencent E: [email protected] ◼ Transforming into a leading online long-video platform with similar Address: 4/F, Henley Building, No.5 Queen's DNA to Netflix. Road Central, Hong Kong ◼ As indicated by name, HengTen (HengDa and Tencent) (136.HK) will leverage the resources of its two significant shareholders in making Ticker (00136.HK) Pumpkin Film the most profitable market leader Recommendation BUY ◼ New team has proven track record in original content production Target price (HKD) 24.0 with an extensive pipeline. Current price (HKD) 13.8 ◼ Initiate BUY with TP HK$24.0 based on 1.0x PEG, representing 74% Last 12 mth price range 0.62 – 17.80 upside potential. Market cap. (HKD, bn) 127.8 Source: Bloomberg, SBI CHINA CAPITAL Transforming into a leading online long-video platform with similar DNA to Netflix. HengTen Networks (“HT”) (136.HK) announced to acquire an 100% stake in Virtual Cinema Entertainment Limited. The company has two main business lines: “Shanghai Ruyi” engages in film and TV show production while “Pumpkin Film”operates an online video platform. Currently one of the only two profitable online video platforms, we expect the company to enjoy similar success as Netflix given their common genes such as: a) a highly successful and proven content development team b) focus on big data analytics which improves ROI visibility and c) enjoyable user experience with an ads-free subscription model As indicated by name, HengTen (HengDa and Tencent) (136.HK) will leverage the resources of its two significant shareholders in making Pumpkin Film the most profitable market leader. -

Chapter 2. Analysis of Korean TV Dramas

저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다. l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer Master’s Thesis of International Studies The Comparison of Television Drama’s Production and Broadcast between Korea and China 중한 드라마의 제작 과 방송 비교 August 2019 Graduate School of International Studies Seoul National University Area Studies Sheng Tingyin The Comparison of Television Drama’s Production and Broadcast between Korea and China Professor Jeong Jong-Ho Submitting a master’s thesis of International Studies August 2019 Graduate School of International Studies Seoul National University International Area Studies Sheng Tingyin Confirming the master’s thesis written by Sheng Tingyin August 2019 Chair 박 태 균 (Seal) Vice Chair 한 영 혜 (Seal) Examiner 정 종 호 (Seal) Abstract Korean TV dramas, as important parts of the Korean Wave (Hallyu), are famous all over the world. China produces most TV dramas in the world. Both countries’ TV drama industries have their own advantages. In order to provide meaningful recommendations for drama production companies and TV stations, this paper analyzes, determines, and compares the characteristics of Korean and Chinese TV drama production and broadcasting. -

CONTEMPORARY DANMEI FICTION and ITS SIMILITUDES with CLASSICAL and YANQING LITERATURE Fiksi Danmei Kontemporer Dan Persamaannya Dengan Sastra Klasik Dan Yanqing

Aiqing Wang CONTEMPORARY DANMEI FICTION AND ITS SIMILITUDES WITH CLASSICAL AND YANQING LITERATURE Fiksi Danmei Kontemporer dan Persamaannya dengan Sastra Klasik dan Yanqing Aiqing Wang Department of Modern Languages and Cultures University of Liverpool [email protected] Naskah diterima: 3 Februari 2021; direvisi: 31 Maret 2021 ; disetujui: 17 Juni 2021 doi: https://doi.org/10.26499/jentera.v10i1.3397 Abstract Danmei, aka Boys Love, is a salient transgressive genre of Chinese internet literature. Since entering China’s niche market in the 1990s, the danmei subculture, predominantly in the form of an original fictional creation, has established an enormous fanbase and demonstrated significance via thought-provoking works and social functions. Nonetheless, the danmei genre is not an innovation in the digital age, in that its bipartite dichotomy between seme ‘top’ and uke ‘bottom’ roles bears similarities to the dyad in caizi-jiaren ‘scholar-beauty’ anecdotes featuring masculine and feminine ideals in literary representations of heterosexual love and courtship, which can be attested in the 17th century and earlier extant accounts. Furthermore, the feminisation of danmei characters is analogous to an androgynous ideal in late-imperial narratives concerning heterosexual relationships during late Ming and early Qing dynasties. Besides, the depiction of semes being masculine while ukes being feminine is consistent with the orthodox, indigenous Chinese masculinity, which is comprised of wen ‘cultural attainment’ epitomising feminine traits and wu ‘martial valour’ epitomising masculine traits. In terms of modern literature, danmei is parallel to the (online) genre yanqing ‘romance’ that is frequently characterised by ‘Mary Sue’ and cliché-ridden narration. Keywords: danmei genre, ‘scholar-beauty’ fiction, yanqing romance, feminisation, ‘Mary Sue’ Abstrak Danmei, alias Boys Love, adalah genre transgresif yang menonjol dari sastra internet Tiongkok. -

Tencent Holdings Limited (SEHK: 700)

Initiation Company Report Internet E INDUSTRY NAM INDUSTRY INDUSTRYME Tencent vs. Alibaba: Why matter and who wins? 5 April, 2016 INVESTMENT SUMMARY ● We initiate Tencent with a BUY rating and a TP of HK$187 because we believe Research Team Tencent has an upper hand in the competition against Alibaba (BABA US, BUY, TP: US$84) to be the top Internet ecosystem in China; Tianli Wen ● Weixin has given Tencent three mandates, in our view: (1) a mobile display Head of Research interface, (2) an online-to-offline bridge and (3) a closed loop business platform. We believe the impact will result in great expansion of Tencent’s business scope; ● In the near term, we expect conversion of PC-based e-sports game to mobile, and +852 21856112 rolling out of Weixin advertising to drive growth. We project top line growth of [email protected] 39% and 26% and non-GAAP operating profit growth of 34% and 25% in 2016/17. See the last page of the report for important disclosures Blue Lotus Capital Advisors Limited 1 China|Asia ●Initiation Internet ● Multi-business Tencent Holdings Limited (SEHK: 700) Realistic imaginations: Initiate with BUY BUY HOLD SELL ● Despite being at the interlude of its growth phases, we believe Tencent’s grasp Target Price: HK$ 187 Current Price: 158.50 Initiation of the mobile Internet ecosystem warrants a BUY. RIC: (SEHK:700) BBG: 700:HK Market cap (US$ mn) 186,069 ● The potential of Weixin as an ecosystem orchestrator is still at the early stage. Average daily volume (US$ mn) 4,722 China’s entertainment spending per GDP still has big room to improve. -

The Chinese Book Market 2016

The Chinese book market 2016 [Editor's Note] An increasing number of readers have begun to show interest in this market report, which has made us very happy. Originally, this report was compiled to provide some information and suggestions for readers in the German publishing industry. Now, many readers from non-German speaking countries (including readers from Mainland China) have also asked for the English edition of the report. The 2016 report may be regarded as a supplement to the 2015 report, with additions reflected in the following three areas: 1) the latest updated figures for the Mainland China market; 2) three major trends in the Mainland China market; and 3) (for the first time!) figures for the Taiwan market. If you are planning to quote from the report, please credit the German Book Office Beijing and include “The Chinese Book Market 2016” as the title. Please notify us if you plan to quote extensively from the report. Chinese book market statistics 1. Book production and book trade According to OpenBook estimates, the Chinese book market’s total retail sales in 2015 came to some 62,4 billion yuan, an increase of 12,8% over the previous year. In addition to the retail market, there is also a market share for libraries, which, according to estimates by industry professionals, has an annual turnover of about 12 billion yuan. These two segments represent the entire Chinese book market, for a total of some 74 billion yuan. Stationary book retailing in China had an overall turnover of 34.4 billion RMB (55.13% of total share) in 2015, which amounts to an increase of 0.3% on a year-on-year basis. -

Circulating Mobile Apps in Greater China: Examining the Cross-Regional Degree in App Markets

International Journal of Communication 13(2019), 2355–2375 1932–8036/20190005 Circulating Mobile Apps in Greater China: Examining the Cross-Regional Degree in App Markets CHRIS CHAO SU1 University of Copenhagen, Denmark XIAO ZHANG Macau University of Science and Technology, Macao This article examines the use of mobile apps and the model of cross-regional communication in the app markets of Greater China and explores the influence of policy, capital, and culture on the mobile app consumption. The cross-regional degree (CRD) of mobile apps is used to measure the circulation of apps in different markets and to identify mobile apps and app producers capable of achieving cross-regional commercial success and of gaining market recognition in Greater China. The final samples include 1,124 mobile apps that ranked among the top 500 in at least two markets. The apps were coded according to market platform, firm age, price, producer listing status, producer location, app genre, and CRD. The consumption of apps in these markets is significantly influenced by policies, company capital, and local cultural tastes. Moreover, mainland China is isolated from other Greater China regions in terms of the app market. Compared with app producers in Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan, app producers in mainland China should consider more marketing strategies targeting audiences in other regions. Keywords: mobile app, policy, capital, Greater China, cross-regional degree, regional cultural taste “The celestial empire,” “the civilization of five thousand years,” and -

Setting out to Grab the Spotlight

22 | Monday, September 23, 2019 LIFE CHINA DAILY HONG KONG EDITION Setting out to grab the spotlight The recent China International Film “The drama is very popular in Indonesia,” says Gandhi Priambobo, & TV Program Exhibition showed founder and CEO of Red and White, a joint venture between Indonesia how determined domestic producers and China which dubbed the drama are to make inroads into overseas into the local language and distrib uted it around the country. markets, Xu Fan reports. A fan of Hong Kong star Stephen Chow, Priambobo says most Indo nesians have limited knowledge or most Chinese fans, it was about China, and the bestknown a shock to see Mei Changsu, Chinese productions in Indonesia the protagonist of the TV still tend to be Hong Kong action series Nirvana in Fire, a The majority of new films starring Jackie Chan. Froyal period drama set in ancient He says the success of Feather TV programs released China, “speaking” Spanish fluently. Flies to the Sky is largely due to the Interestingly, the character — a simultaneously in growing curiosity about China’s leader of a group of swordsmen — China and abroad booming economy and interest in can also “speak” English and a few how Chinese businessmen conquer more other languages. also saw a obstacles and earn success. These are all different foreign lan remarkable rise in In the meantime, more Chinese guagedubbed versions of Nirvana online views production companies are scouting in Fire, a phenomenal worldwide for overseas locations thanks to big hit show that has garnered more overseas.” ger budgets and profits, industry than 16 billion views online. -

China Story Yearbook 2016: Control Are Members Of, Or Associated with CIW

CONTROL 治 EDITED BY Jane Golley, Linda Jaivin, AND Luigi Tomba C HINA S TORY YEARBOOK 2 0 16 © The Australian National Univeristy (as represented by the Australian Centre on China in the World) First published May 2017 by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Control / Jane Golley, Linda Jaivin, and Luigi Tomba, editors. ISBN: 9781760461195 (paperback); 9781760461201 (ebook) Series: China story yearbook; 2016. Subjects: Zhongguo gong chan dang--Discipline | China--Environment policy--21st century | China--Social conditions--21st century | China--Economic conditions--21st century | China--Politics and government--21st century. Other Creators/Contributors: Golley, Jane, editor. | Jaivin, Linda, editor. Tomba, Luigi, editor. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. This publication is made available as an Open Educational Resource through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike 3.0 Australia Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/au/ Note on Visual Material All images in this publication have been fully accredited. As this is a non-commercial publication, certain images have been used under a Creative Commons -

Comprehensive Evaluation Model of Network Drama Hotness Based On

2019 5th International Conference on Economics and Management (ICEM 2019) ISBN: 978-1-60595-634-3 Comprehensive Evaluation Model of Network Drama Hotness Based on Factor Analysis Xin-Xing ZHAO1,a,* and Pei-Yi SONG1,b 1School of Economics and Management, Communication University of China, Beijing, China [email protected], [email protected] *Corresponding author Keywords: Network Drama Hotness, Factor Analysis, Comprehensive Evaluation Model. Abstract. Firstly, this paper constructed an index system for the comprehensive evaluation of network drama hotness from the two dimensions. They were characteristics of commercial success and characteristics of the popularity of network dramas. Then it used the factor analysis method to verify the rationality and validity of the index system from an empirical perspective, established the weight of two common factors, and obtained the evaluation model of comprehensive factor scores. The conclusion of empirical analysis showed that 62.373% of network drama hotness come from the factor of characteristics of commercial success and 29.287% come from the factor of characteristics of the popularity. Introduction The main quality measurement index of traditional TV series is audience rating [1]. With the advent of the multi-screen era, view counts have gradually become an important indicator to measure the influence of TV series or network dramas. However, neither audience rating nor view counts is enough to objectively and comprehensively measure the hotness of TV series or network dramas. Many scholars have conducted researches on this issue. For example, Chunlian Liu interprets the reasons for the imbalance between word of mouth and audience rating of TV series the Rise of Phoenixes from producer, audience and communication environment [2].